Can John McCain Survive the Year of Trump?

With a nasty challenge from the right and a credible threat from the left, the Arizona senator is caught in a vise of his own making.

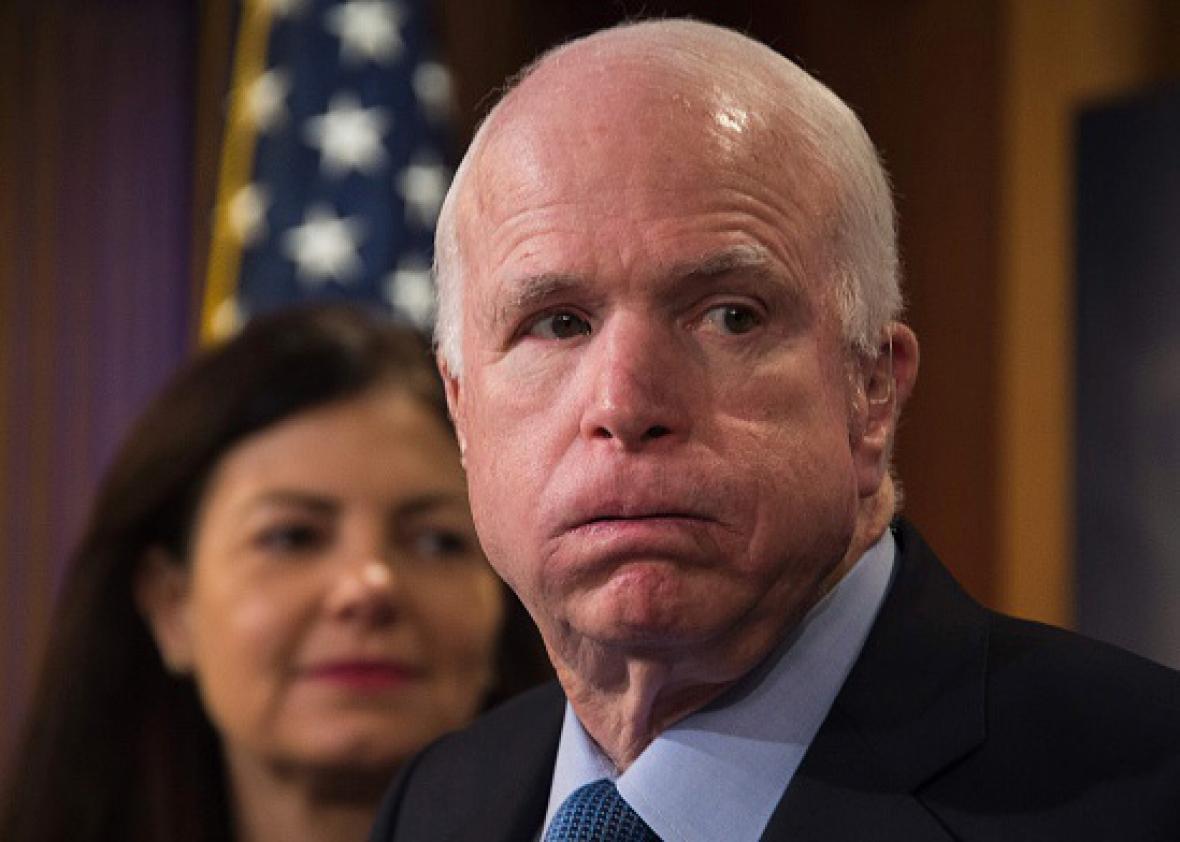

Jim Watson/AFP/Getty Images

Sen. John McCain had a bad day on June 16, which means that Stephen Sebastian had a good one. McCain was speaking to reporters on Capitol Hill several days after the Orlando nightclub shooting and assigned blame for the incident where he saw fit.

“Barack Obama is directly responsible for it,” he said, “because when he pulled everybody out of Iraq, al-Qaida went to Syria, became ISIS, and ISIS is what it is today thanks to Barack Obama’s failures.”

McCain has frequently argued that Obama made a strategic blunder in carrying out the 2011 withdrawal of Iraq. He believes this. But the personalization of his criticism during a tragic and toxic week in American social and political life seemed incongruously aggressive for the moment.

His communications department soon set about cleaning up the remarks. “I misspoke,” the senator said in a press release issued several hours later. “I did not mean to imply that the President was personally responsible. I was referring to President Obama’s national security decisions, not the President himself.”

Why the clarification and the additional scrutiny that invites? McCain is up for re-election this year, and he can’t just throw raw meat to the base as he did in 2010, when all he had to do was get through his primary. Arizona was a safely red state then, and his Democratic competition that autumn was little more than token.

The task is more delicate this time. He has a legitimate challenger in Kelli Ward, a former Arizona state senator whom he can’t write off ahead of the Aug. 30 primary, and the Arizona GOP’s Trump-inflamed hard-right flank is eager to get another shot at him. His general election competition, assuming he gets that far, is anything but token: He is going up against Rep. Ann Kirkpatrick, a sitting member of Congress who knows what it’s like to run in tight, expensive races. Demographic trends have already numbered Arizona’s days as a safe red state. Democrats hope that Donald Trump is the catalyst they need to hustle the state into their column.

That night, at an event in Phoenix, Stephen Sebastian was beaming. Sebastian is Ward’s communications director. He’d been out of pocket at another event earlier in the day when news broke of McCain’s comments. After he checked his phone and saw it blowing up, he scrambled to put out a statement. I saw his handiwork in Phoenix, a gleefully acerbic effort with the headline, “WARD: McCain ‘Directly Responsible’ for ISIS.” In no way did Sebastian seem nervous that the sentiment might be received as a step too far in response to McCain’s own overreach, and Ward herself would later read the statement aloud to a table of Tea Partiers.

“As we got used to during his 2008 presidential campaign, John McCain has once again thrown a punch at Barack Obama and immediately apologized for it, bowing to lick the boots of the political correctness police—Not surprising for the ultimate establishment insider,” the statement read. “I, however, am not afraid to place the blame right where it belongs: John McCain is ‘directly responsible’ for the rise of ISIS.”

It was a Trumpian statement. On policy, it hit the Republican establishment on the “globalist” policies with which the nationalist Trump wing of the party takes issue—nation-building abroad, open borders at home. More important to Ward’s campaign and a frustrated element of conservatives than the substance of the complaint, though, was the style: She had thrown a nasty punch that elites would likely tut-tut, and she would stand by it. As we saw with Trump, saying something controversial, not backing down, and getting away with it is just as central to earning the support of Republican hard-liners as the content itself. John McCain learned this firsthand a year ago.

As the Ward camp hit McCain for exemplifying everything Republican presidential primary voters had rejected by nominating Trump, the Kirkpatrick campaign criticized McCain for his reckless Trumpism. “Elected leaders have a moral duty to work together to root out terrorism and keep Americans safe,” the Kirkpatrick campaign’s statement read. “But today, we saw John McCain cross a dangerous line in comments that undermine our Commander in Chief on national security issues—at the very moment the president was in Orlando to comfort victims’ families. It’s difficult to imagine the old John McCain being this reckless with something so serious. John McCain has changed after 33 years in Washington.” On the Kirkpatrick campaign’s website, the statement is squeezed between two other news releases connecting McCain to Trump.

Could John McCain lose? By his own admission, yes. “If Donald Trump is at the top of the ticket, here in Arizona, with over 30 percent of the vote being the Hispanic vote, no doubt that this may be the race of my life,” McCain said at a private event in early May. The polling in neither his primary nor his prospective general election matchup is all that cushy.

Trump’s position at the top of the ticket gives his rivals on the right and the left a feeling that this is the cycle in which their respective prophecies will be met. Immigration hard-liners in this hot-tempered border state—“the crazies” of whom McCain once spoke—hope Trump’s triumph is the sign from God that this is the year they’ll retire McCain through a primary. Democrats see McCain’s defeat at the hands of Kirkpatrick as the herald of tomorrow’s blue Arizona, a state whose politics will be shaped by the growing Latino share of the electorate.

Each camp may be more given to wish-casting than it admits. The right-wing resistance to McCain in Arizona has earned plenty of national press over the years, but it’s never proven to be more than a vocal minority. And Democratic hopes of turning Arizona blue now sound an awful lot like Democratic hopes of turning Texas blue did a couple of years ago.

Neither of these threats is catching McCain by surprise, and both the campaign he’s assembled and the candidate it’s tasked with re-electing are skilled operators. He is running a tight, merciless campaign, one at odds both with the caricature of McCain as a hopeless old fud and with the spontaneity of his campaigns of yore. This is John McCain, in a bind partly of his own devising, doing what he needs to do to squeeze another six years out of history.

The Primary: Chemtrail Kelli and the Woodchipper

At 6:30 p.m. on June 16, the weather was cooling to a balmy 100 degrees outside the Quality Inn Phoenix Airport. That’s where Kelli Ward and a handful of other politicians running for lower offices had convened for a meet-and-greet with members of the Ahwatukee Tea Party.

Ward, 47, is from Lake Havasu City on the state’s western border. She represented the area in the state Senate for three years before turning full-time to her campaign against the most famous Republican officeholder in the country. Lake Havasu is home to London Bridge, built in the 1830s, which a businessman purchased from the city of London in 1968 and subsequently had rebuilt block-by-block. It is also a popular regional spring break destination. “It’s our Daytona Beach,” as one Arizona operative put it to me. “That’s the politest way of saying it.” Lake Havasu City is very conservative.

So is Ward, and so were the 20 or so local Tea Party members who showed up that night in Phoenix. Ward doesn’t have the advertising budget or the support from outside groups that the senior senator from Arizona does. National groups that have funded conservative primary challengers in the past and had their eye on McCain this year, such as the Senate Conservatives Fund or the Club for Growth, have so far demurred from signing on with Ward. With so much of her campaign cash already spent on building up an organization, Ward advertises the old-fashioned way: meeting voters one by one, at as many events as possible, even if only a handful of people show up.

Gage Skidmore/Flickr CC

Ward is warm and eager to impress, always smiling even when she’s releasing a punch. She speaks rapidly, without pause for breathing, as she gives the elevator pitch to conservative voters around the state who know they may not like McCain but haven’t a clue who his opponents are. She drops her endorsements less to boast than to signal her ideological allegiances—Phyllis Schlafly, Chris McDaniel, Ron Paul, Mark Levin—and mentions approximately every 20 words that she’s a “military wife,” as important a biographical plank as any in a race against the country’s most famous veteran. Ward also doesn’t let slide McCain’s election-season appeal to his own military credentials as a signifier of foreign policy know-how. “John McCain was in the military,” she explained to me, but “he was never a commander in the military, that I know of. He was never somebody that was making strategy.” (It’s a softer version of Trump’s infamous reference to McCain’s five-and-a-half-year captivity in North Vietnam. “He’s not a war hero,” Trump said. “He was a war hero because he was captured. I like people who weren’t captured.”)

Ward’s is an insurgency with the flavor of its native state. She mixes in typical sloganeering about how “it’s time to retire John McCain,” who is “not the conservative he claims to be,” with more colorful jingles: “I am ready to mix the mortar to fix the border!” she would say the following day at a roundtable in Prescott.

“I have a question that’s important to me and the 27,000 readers of my website,” said one attendee at the Tea Party event. Middle-aged and sporting long, damp, curly locks reminiscent of Rick James, the man wore a T-shirt on which “ISIS” had been crossed out, with a bomb instead of a dot atop the second I. Next to that graphic was a likeness of Donald Trump, holding a gun from the business end of which erupted a mushroom cloud. Above Trump it read “I’VE JIHAD IT!” and beneath all of this, finally, came the quote, “We’re gonna knock the hell out of ISIS.” His question was whether Ward supports Donald Trump.

Ward is on board with Trump, but she has her qualms. Like Trump, she’s a border hawk; she goes so far as to support “turning off” immigration until “we find the people here illegally.” A closer analog to her conservatism, though, would be Sen. Ted Cruz, and she gushes about the possibility of serving with him. Like Cruz, she’s leery of the trade protectionist planks of Trump’s campaign, and she hopes in the Senate to provide a check on Trump’s extra-constitutional impulses. She’s also spoken out and introduced statewide legislation against National Security Agency mass surveillance programs on Fourth Amendment grounds.

Breaks from mainstream Republican orthodoxy like the latter expose Ward to the largess of mainstream Republican donors. McCain, who chairs the Senate Armed Services Committee, is running a campaign focused on national security, which suits his purposes in primary and general election terrains. A hawk if ever there was one, McCain—who spent the Fourth of July with the troops in Afghanistan and fretted about a deficit of soldier deployments there—doesn’t have time for reforms that might even marginally handcuff the country’s surveillance capabilities. And he believes that a majority of voters won’t, either, after the attacks in San Bernardino and Orlando. He’s probably not wrong about that.

At both the Tea Party meeting and the coffee shop roundtable in Prescott the next day, one of the first things the assembled voters wanted to know was: What was all the stuff they were hearing about Ward—those ads that pop up whenever they’re watching Fox News, those pamphlets that keep turning up in their mail? Was it true?

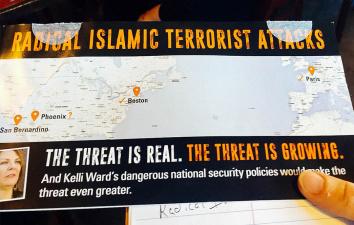

In Prescott, one woman brought in a mailer she’d received and handed it to the candidate. Ward laughed; this wasn’t the first time someone had shown it to her. Atop the mailer were the words “RADICAL ISLAMIC TERRORIST ATTACKS” in a chilling typeface. Beneath it was a map marking Paris, Boston, San Bernardino, and Phoenix. A check mark appeared next to the first three cities, while Phoenix bore a question mark. “THE THREAT IS REAL. THE THREAT IS GROWING,” it said. “And Kelli Ward’s dangerous national security policies would make the threat even greater.”

Jim Newell

“This is the nicest one they’ve sent out,” Ward’s mother, Lorraine Byrd, who travels with her daughter on the trail, said to me.

Who is “they”? The assault on Ward is a joint production from the McCain campaign and, in the case of this flier, an entity known as Arizona Grassroots Action. Naturally, Arizona Grassroots Action is a pro-McCain super PAC based out of Alexandria, Virginia, whose major donors include former WWE CEO and Connecticut Senate candidate Linda McMahon, billionaire Ron Perelman, and finance titans Paul Singer and Gregory Wendt. It shares an office address, according to Federal Election Commission filings, with Friends of John McCain Inc.—the official McCain campaign committee. The two entities are “segregated” from each other, the McCain campaign insists. But let’s at least posit that the necessities of battle have led McCain far from the high-minded forbearance of his McCain-Feingold days.

Ward laughs off the charges as ridiculous—and they are, though well within the norm of political campaigning—and she thanks McCain for helping to build up her name recognition.

The McCain campaign would use a more traditional term for what they’re doing: defining its opponent. Or as the armchair mercenary operatives would call it in private: killing its opponent.

The McCain campaign made a legendary killing of its last right-wing primary opponent, J.D. Hayworth, in 2010. Hayworth was a television personality who parlayed that into a 12-year stint in Congress, after which he returned to the airwaves. As a talk radio host he was deeply critical of McCain, especially over McCain’s work with Sen. Ted Kennedy on immigration reform. McCain’s associates took umbrage and tried to get Hayworth off the air by filing complaints with the radio station. That backfired.

“To some extent, [they] almost pushed him off the air and into the race,” recalls Jason Rose, an Arizona consultant who served as a senior adviser to Hayworth’s campaign until spring 2010. This was the year of the Tea Party wave, and for a while, Hayworth was able to keep his head above water amid a $20 million-plus bombardment from McCain.

That June the press “discovered” certain infomercials Hayworth had starred in. As pitchman for the National Grants Conference, Hayworth urged viewers to sign up for seminars that would teach them how to get grant money from the federal government—or, as the on-screen text read, “FREE MONEY.” From the government! The production aesthetic of the infomercials is recognizable as “obvious screeching scam.” As Talking Points Memo reported at the time, the company had received an F from the Better Business Bureau and complaints from 32 state attorneys general.

Rose—who supports McCain this year—recalls catching up with a McCain staffer from the 2010 campaign a couple of years ago to swap war stories. “There was a lot of concern about J.D.,” the staffer told him, “but then they got a tip about what really turned that race … they uncovered this video.” Rose remembers talking to Hayworth’s campaign manager at the time: “And he said something like, ‘Yeah, J.D. thought that might be a problem.’ ” McCain won the primary by 24 points.

If McCain prevails in the primary, we can be pretty sure what the defining kill shot was, the two words by which everyone remembers the 2016 Arizona Republican Senate primary.

Chemtrail Kelli.

In June 2014, Ward, then a state senator, convened a hearing with members of the Arizona Department of Environmental Quality to address, among other things, constituent concerns about “chemtrail” conspiracy theories. Chemtrails are a genre of conspiracy theory unto themselves; the gist is that jet contrails don’t simply consist of water vapor byproducts, but also of chemical agents being sprayed onto an unsuspecting public for nefarious purposes such as altering human behavior. A lot of people in Ward’s district had been concerned about blood tests they’d been receiving, and rumors began circulating.

There’s no evidence that Ward bought into these rumors. Ward’s introductory remarks, which she gave before ceding the stage to experts, are actually sort of funny. She searches for the right euphemism for the conspiracists who’ve clearly been annoying the hell out of her and her office about this, and she settles on “relentless” before quickly adding, “That’s not a bad thing!”

Her constituents were worried, and Ward felt it was her duty to hold a public information session, no matter how absurd the concerns. “The only people who would make a story out of that,” she told me, “are the political elite, who don’t think you need to respond to constituents concerns, and the media who love to hype things up because it brings readership.” The press labeled her a conspiracy theorist at the time, and now the McCain campaign and its super PAC, with their piles of cash, have revived the story. “CHEMTRAIL KELLI FUELS CONSPIRACY THEORIES AT TAXPAYER EXPENSE,” a spot from Friends of John McCain blares out, while an ad from the campaign’s super PAC officemate spells a number of complaints about Ward in contrail skywriting.

“They say politics is like being put through a wringer,” Ward said at the Ahwatukee Tea Party event, “but really it’s a woodchipper.” She then pointed out something I had missed. Among the 20 or so people at the event, there was one other relatively young person who wasn’t a reporter or a candidate. Dressed in a plaid button-down, he’d come to the event late and didn’t say much to anyone. After sitting at a roundtable with Ward, he typed some notes on his phone and left early. He was a tracker, and he had been recording the event with his phone, only the tip of which was visible from his shirt pocket.

One of Ward’s great frustrations is that she can’t get McCain in a one-on-one. There are two other weaker-polling candidates on the ballot, Alex Meluskey and perennial gadfly Clair Van Steenwyk, both of whom Ward has repeatedly urged to get out of the race since they’re just diluting the opposition to McCain. There are rumors in right-wing Arizona circles that associates of McCain are covertly propping up Meluskey’s campaign for this reason, rumors that both Ward’s communications director and Ward herself passed on to me, even while noting that the relationship is “impossible to prove.” McCain’s spokeswoman, Lorna Romero, dismisses these rumors as paranoia. “It’s shocking that she would even allege something like that,” Romero says.

If Ward goes down, even in a state with so much right-wing rage at McCain, the explanation needn’t stretch into conspiracy. McCain has done this before; he has money, and he’s not taking his opponent lightly, even if she’s not nearly as well-known as him. These are experienced political professionals, and it’s not a coincidence that McCain drew Ward as his main primary challenger instead of, say Reps. Matt Salmon or Dave Schweikert, two conservative recruits who declined to run.

“They knew that [McCain] was taking this as the race of his life,” says Sean Noble, an Arizona operative and former chief of staff to Rep. John Shadegg. “They saw the numbers as well as he did. They took a pass for a reason.”

The General: Ann Kirkpatrick and the Vault

Just southeast from downtown Phoenix and across the river from Phoenix Sky Harbor International Airport rests Tempe, a city of 168,000 people that’s home to Arizona State University. A short walk from the campus is an old bank building that looks abandoned from the outside but inside is teeming with a dozen or so young people making calls and chatting in the open atrium where customers once queued to speak to tellers.

The old bank now serves as headquarters for Kirkpatrick for Senate, where these young employees are trying to win a U.S. Senate race for an Arizona Democrat for the first time in 28 years.

“Let’s show you the vault,” Kirkpatrick’s communications director, D.B. Mitchell, told me when I visited.

The vault has been converted into a room for opposition research on John McCain. Inside the foot-thick door—which, I was told, had been rejiggered to ensure that it can’t be locked shut, trapping hapless staffers inside—were two computers used solely for digging through McCain’s career in politics and the forgotten iterations of his picaresque journey. A rotation of staffers and interns, amply supplied by the massive public university down the street, sit in the vault and rummage through McCain’s many previous lives.

Tom Williams/CQ Roll Call

“One of our interns was watching footage of a 1999 presidential debate” between McCain and Bush, Kirkpatrick campaign manager Max Croes was saying in his office, “and said to me, ‘Did you know there was this guy named Bill Bradley who ran against Al Gore?’ ” If young people, even ones interning for Democratic political campaigns, can’t remember a major Democratic figure from the late 1990s, how much have they never known about McCain? And how much has everyone else forgotten?

Do people remember, for instance, the McCain who was once something other than an establishment, Chamber of Commerce Republican? Do they remember his brush with scandal in the 1980s as a member of the so-called Keating Five? His reinvention over the next decade as a campaign finance reform prophet and an unpredictable vote, a good-government “maverick” who made an uncomfortable habit of calling out party leaders’ wasteful spending projects? Surely they remember the McCain who added to all of the above a thirst for military adventurism and who by 2000 became, in his mind, a sort of latter-day Teddy Roosevelt. This was the man who for a fleeting moment looked as if he might wrest the nomination from establishment favorite George W. Bush and who finally earned his turn as the party’s nominee in 2008.

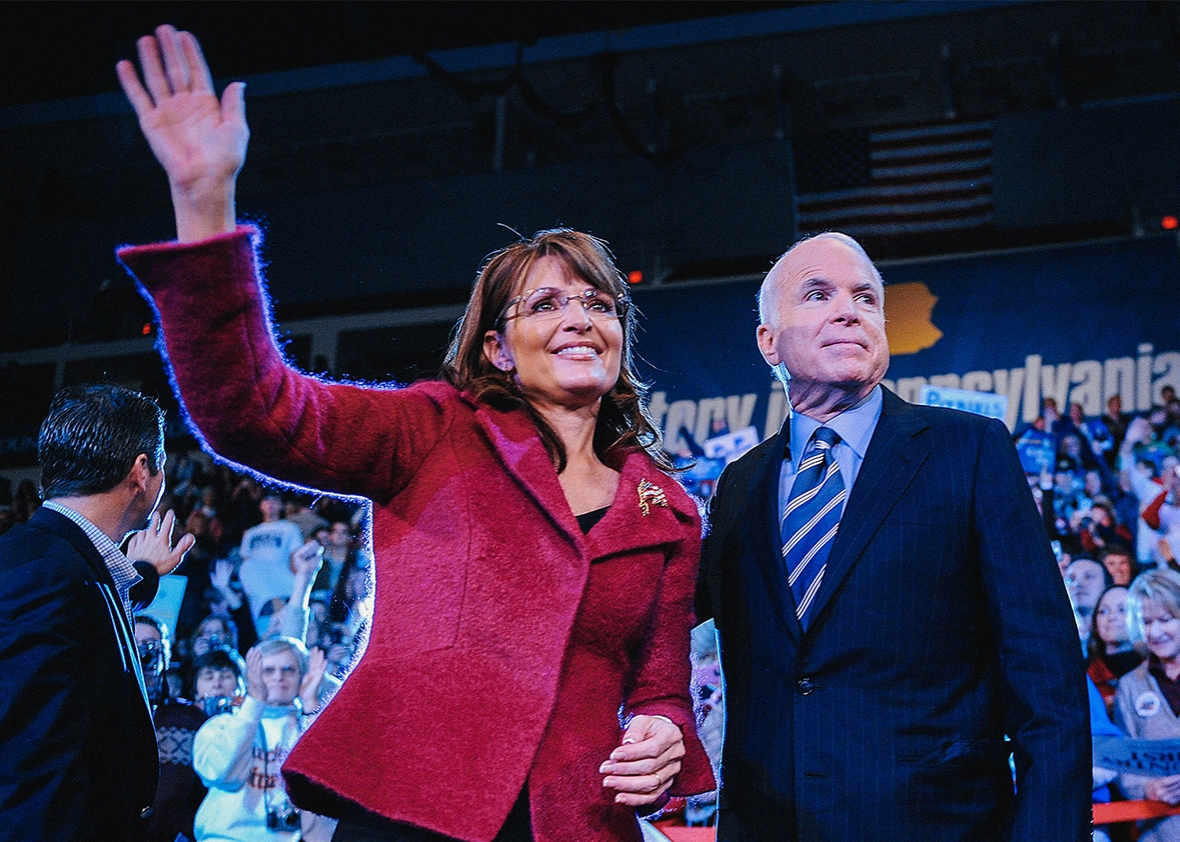

It’s incredible to think now that McCain was ever the one who gave Republican leaders headaches. Right now that title belongs to Sens. Ted Cruz, Mike Lee, and Rand Paul and roughly one-sixth of the House Republican Conference, while McCain is just the guy trying to push appropriations bills through. The Tea Party would have come about anyway after Sen. Barack Obama beat McCain in 2008. But don’t forget, either, that it was McCain who that year enabled the anarchic right by rushing Alaska Gov. Sarah Palin onto the national scene. Even today he will not speak negatively in public about his choice of Palin for vice president.

The Tea Party turned hard against mainstream conservatives like McCain, while McCain, in first lunging to the cranky right to win re-election in 2010 and thereafter settling into his role as a party man, lost some of the shine on his halo among independents. Now here he is today, just throwing money at super PACs and telling them to get rid of his problem.

Arizona Democrats, noting McCain’s sagging popularity, had their eye on him this cycle even before it was known that Republican primary voters would make an immense in-kind contribution to the Democratic cause by nominating Donald Trump for the presidency. In 2014, a survey from the left-leaning Public Policy Polling found McCain to be the “least popular senator in the country”; McCain referred to this as “bogus.” In a May PPP survey (commissioned by progressive group MoveOn, as McCain’s campaign likes to point out), McCain’s overall approval rating sat underwater at 34 percent to 52.

“Everyone in Arizona has a story about how John McCain’s been an asshole to them,” Democratic consultant Andy Barr says.

The Kirkpatrick campaign’s message to those who do remember McCain’s popular “maverick” iteration is that he’s changed, while the message to younger voters is that he’s always been this bad.

And the message to everyone is that John McCain supports Donald Trump’s candidacy.

David Jolkovski/Washington Post via Getty Images

Not a single Arizona Republican operative I spoke with would describe McCain’s support of Trump as anything other than a political necessity. He’s just doing what he needs to do. But it’s not good enough, Democrats say, for McCain to say he supports the nominee—even after having been personally insulted last year—but then to keep his distance and act as if they’re wholly separate entities. He can’t have it both ways. In the age of Trump, he can’t be the loyal Republican soldier and the independent-minded center-right ally of Hispanic communities.

Kirkpatrick, 66, is familiar with tight elections. She won her first race in Arizona’s 1st Congressional District in 2008 in a year that was horrific for Republicans all around, but especially in that district. The congressman she was seeking to replace, Rep. Rick Renzi, didn’t run for re-election due to his 35-count indictment involving various shady investment deals and acts of political corruption. Kirkpatrick won the district by 16 percentage points that year, a luxury she’s never enjoyed since. She lost the seat in the next election to Rep. Paul Gosar then retook it in a 2012 squeaker after the district was redrawn and Gosar had moved to the 4th District. She narrowly won re-election in a brawl of a 2014 campaign that, with total expenditures of $17 million, was one of the most expensive House races in the country.

Arizona’s 1st Congressional District is enormous. Covering roughly half the state, it includes the Hopi, Navajo, and Apache reservations to the northeast and stretches west to gobble up Flagstaff—where Kirkpatrick is from—and the Grand Canyon. At the bottom it extends southwest to include the Sonoran exurbs south of Phoenix. Running campaigns in this district is good preparation for a statewide campaign: It requires advertising in the Phoenix, Flagstaff, and Tucson media markets; strong relationships with Native Americans; and an intricate knowledge of rural communities dotted across the terrain. “It’s like running for mayor of a million different small towns,” Sean Noble says.

But running in Arizona’s 1st District isn’t perfect preparation for running a statewide race. The shape of the district suggests a curious lumbering giant who approaches major population centers, sees all the people, and holds back. About 70 percent of the votes in Arizona are in Maricopa County—the blue city of Phoenix, phalanxed by the deep red suburbs of Mesa, Gilbert, Scottsdale, and Glendale—and Pima County (i.e., Tucson). It’s these consistently fast-growing, demographically shifting hubs that Kirkpatrick has never had to win before where her bid against McCain will either be won or lost.

Kirkpatrick announced her Senate candidacy in May 2015, when the political world still saw Donald Trump’s dabbling with a presidential run as little more than his quadrennial play for attention. I asked Kirkpatrick what prompted her to give up her congressional seat for a ploy so risky as challenging McCain.

“I did a Democratic precinct analysis, and I looked at the underperforming Democratic areas of Arizona,” she says, “and I realized that’s where we have to focus, and that’s where we have to perform.” She looked at Richard Carmona’s race against Sen. Jeff Flake in 2012—a wake-up call for the Arizona Republican Party—in which Carmona lost by only 3 percentage points. “I said, OK, where do we pick up those 90,000 votes? And how do we do that? And once I figured that out, I was like, ‘We can do this.’ ” The precincts she was looking at were largely in the Phoenix and Tucson areas.

Registering tens of thousands of new voters, and then ensuring that those voters turn out, is the Arizona election year goal for Mi Familia Vota, a national nonprofit that promotes civic engagement among Latino communities. It has two offices in Maricopa and one in Tucson. Francisco Heredia, MFV’s national field director, walked me through its efforts at his office in Phoenix. The first phase of its program, from January through May, was to help legal permanent residents apply for citizenship ahead of the election, a four- to five-month process. The second phase, going on now, is to register the new citizens, and the third phase is to turn out the vote.

Much of Arizona’s voting is done by mail. The solidly Republican state government in 2007 passed a law allowing for permanent early (or absentee) voting, Heredia says, because at the time it believed such a system was beneficial to Republicans. As state demographics shifted and it turned out that easier access to the ballot only helped Democrats, the legislature determined that voter fraud was a very serious threat. One of MFV’s practices in the past had been to collect the mailed ballots of Latino voters with whom it had built trust and ensure that the ballots were turned in. In March of this year, though, the state government passed a law making “ballot harvesting,” as it’s known, a felony. “The legislature, led by Republicans, really created this environment that there is voter fraud happening, when there’s nothing going on,” Heredia says. A 2013 analysis from the Arizona Republic found a total of 34 voter fraud cases since 2005 in Maricopa County.

Kirkpatrick’s task, like the tasks of all Senate and House challengers in competitive races this year, is to fuse her Republican opponent with Donald Trump. In Arizona doing so would allow her to maximize Latino and youth turnout—there’s some overlap between the two, as the average age of Latinos in Arizona is mid-20s while for whites it’s mid-40s—and sway more traditional swing voters. It’s among those traditional swing voters where a female candidate helps. “Basically, the entire swing demographic in Arizona is white suburban women,” says Andy Barr. “There’s not much else in the swing demo.”

But the electoral pivot of the race, as Democrats see it, is the young Latino voter, who they believe could inaugurate the bluing of Arizona, given sufficient turnout. The share of Latinos as a percentage of the Arizona vote has increased from single digits in the 1990s to 12 percent in 2004, 16 percent in 2008, and 18 percent in 2012. Arizona Democrats are hoping for 18 to 20 percent this cycle.

Will that be enough?

Rep. Ruben Gallego, a freshman member of Congress representing a safe Democratic district in Phoenix, thinks the magic number is still 18 percent of the vote. Anecdotally, at least, what he’s hearing in his district is that new, young Latino voters who don’t have a relationship with McCain are viewing him as an extension of Trump. “Latinos are now seeing McCain and Trump as one and the same,” he says, “and even tying things that your average voter would not normally tie together. For example: John McCain not supporting the president’s Supreme Court pick? In their minds, from what I’m hearing, it’s telling them that he wants Trump to pick the next Supreme Court justice. So it’s just starting to jell together.” (The Kirkpatrick campaign has been flogging the Merrick Garland obstruction hard as part of its “McCain has changed” effort.)

Robyn Beck/AFP/Getty Images

Republican operatives, even ones who think that Arizona will eventually turn blue, just don’t see this as the year. Eighteen or 20 percent isn’t high enough, and McCain, though damaged goods, is still too strong of a brand for Trump to drag down. “I believe that’s likely the case”—that Arizona turns blue due to demographics—“sometime in the 2020s,” Noble says. “The demographics just aren’t moving fast enough, because even though the population has increased, they just don’t turn out.”

Mike Madrid, a Sacramento, California-based GOP consultant who studies Latino voter trends and has warned the GOP about its rhetoric toward communities of color, believes that poor voter turnout plus McCain’s far better-than-average numbers among Latinos won’t even make this close. Sure, he says, McCain’s numbers among Latinos have dipped over the course of his re-election campaigns—but it’s been gradual, and his peak was really, really high. He says it’s not “likely” they fall beneath 40 percent, even with Trump atop the ticket. “McCain is the Republican elected official that has done the best with Latino/Hispanic voters [of] any candidate in history,” Madrid says. A 2-percentage-point increase in the Hispanic share of the electorate won’t make a difference if Latino voters still break in the 40s for McCain. If there is a collapse in McCain’s trend line rather than a continuation of the gradual decline—say, plummeting to a 30 percent share of the Latino vote—then Madrid estimates the Hispanic percentage of the electorate would still need to be something like 25 percent.

The highest growth rates, he says, are really in Pima County instead of Maricopa. “It’s a different demographic,” he explains. “It’s a much more rural area. It’s much more recently migrated. It’s much more recently naturalized. It’s much more migratory, much more Spanish dominant. All of those are indictors of voting for Democrats. They are also equally strong or stronger indicators of not voting at all.”

It’s not like the figure atop the Democratic ticket this cycle is a particularly popular candidate, either. Just as the Democrats will try to link McCain to Trump, so too will Republicans try to link Kirkpatrick to Clinton—on both policy and on style. Republican politicos in Arizona are unimpressed with Kirkpatrick and tag her with some of the same descriptions they might Clinton: scripted, guarded, overly protected by her handlers, afraid of mixing it up with the people or speaking off the cuff.

“John McCain is a very public figure,” says Lorna Romero, McCain’s spokeswoman. “He enjoys going out to public events. He enjoys interacting with voters. He enjoys talking to the media. That’s a real contrast with him and his challenger. She is a much more private candidate. … She is much more comfortable in a controlled environment, and that’s just the reality.” The McCain campaign and other Kirkpatrick detractors point frequently to a clip of Kirkpatrick walking out of a town hall meeting during the summer of 2009, when quite a few members of Congress found themselves face-to-face with livid voters across the nation. (The Kirkpatrick campaign disputes the account, noting that it wasn’t a “town hall” per se but a meet-and-greet with constituents that Tea Party protesters disrupted.)* Like a lot of those members, Kirkpatrick lost re-election that fall. Per the McCain campaign, that experience was the reason her public image has become Fortress Kirkpatrick.

The Kirkpatrick campaign, in my experience, does have its barriers. I was able to secure 16 minutes with the candidate, by phone, with the communications director listening on. (It was admittedly a busy day.)

Yet that was 16 minutes more than I got with the “very public figure” who “enjoys talking to the media.” In McCain’s 2000 heyday, reporters would famously spend hours shooting the breeze with the senator on his campaign bus. This was largely a strategic decision, as McCain needed to try something dramatic to increase his exposure if he was ever going to have a fighting chance against Bush. But he also enjoyed being the Anti-Candidate who refused to be buttoned up. Now he’s another endangered senator, fending off grassroots organizing from the right and the left, dutifully following his staff’s instructions about staying on message.

* * *

“Let’s go call them terrorists,” a young man named Rob, wearing a hat that read “Stop Islam,” said outside the Veterans Memorial Coliseum in Phoenix. Donald Trump was a couple hours away from holding a rally.

Rob was expecting large protests that day. There had been some nasty ones the last time Trump held a megarally in the valley, and only weeks earlier, protesters had turned violent on Trump supporters at a rally in San Jose, California. Protesters in Arizona have been a well-organized federation, I was told, ever since the fight over SB 1070 in 2010. Several volunteer security groups—one of them a biker group—positioned themselves outside the arena to keep a check on the situation and safely escort earnest Trumpkins to their cars.

I started following Rob and a few of his friends toward the site of the protesters whom he claimed he was going to call terrorists. We walked about five minutes, and he realized that there was probably another 10-minute walk to where had he heard some protesters were, and then I turned back. It was 114 degrees in the middle of the day.

The protests never really materialized, probably because of the weather. The arena wasn’t full, either, probably because people didn’t want to leave their homes in the heat. And also because, well, what new was there to see?

McCain didn’t show up at the Trump rally. Aside from him and Sen. Jeff Flake, who’s not up for re-election and who, unlike McCain, hasn’t endorsed Trump, just about every other Republican worth his or her golfer’s tan was at the stadium. (“Yes,” Flake reportedly said to Trump during the candidate’s testy meeting with Senate Republicans, “I’m the other senator from Arizona—the one who didn’t get captured—and I want to talk to you about statements like that.”) Sheriff Joe Arpaio, himself up for re-election this year, was there. One enthusiast in attendance asked him to smile. “Smile?” he said, incredulous. “I never smile.” He told me he had no preference in the McCain-Ward fight but hoped the best candidate would prevail: “What do you think I’m with Trump for?” Former Gov. Jan Brewer, state party chairman Robert Graham—who rejected any implication that his state might be turning blue—state treasurer Jeff DeWit, and state House Speaker David Gowan all took turns speaking before Trump. Then Trump came out and did his Trump thing for 45 minutes, and there were the usual chants of “Build the wall!” and call-and-response bits about how it will be Mexico that pays for it. And then everyone went back outside into the heat and the parking-lot traffic.

John McCain will turn 80 the day before his primary. What compels him to look at what’s going on in his state—in his country—and decide, “I want another six years”? His campaign would give me only the usual talk about how he enjoys being in the mix, fighting for Arizona, keeping America safe. The more prosaic explanation for why McCain wants another six years is that he would retain a lot of power in the Senate as a committee chair. Other explanations tend to put McCain on the couch. There is the theory, which Noble offered, that McCain doesn’t want to retire because both his father and grandfather either died or didn’t know what to do with themselves after their retirements from the Navy.

No one I spoke with at the Trump rally seemed eager to reach for the Freudian explanation. These people simply don’t like McCain. They think he’s a creature of Washington who’s been around too long and answers only to elite interests and national media concerns and just needs to go.

But even in their denunciations there was a tinge of respect, even acceptance. They paid tribute to his military service; they acknowledged his heroism. Jason Rose, the consultant who worked for J.D. Hayworth, had mentioned to me the amazing thing with McCain: No matter how sick of McCain his detractors can get, they always have the ability to be stunned anew when they hear his biography for the hundredth or thousandth time.

Let’s put McCain on the couch ourselves: If the stars had aligned better for him and handed him, at age 80, an easy path to re-election, perhaps he might have been less inclined to do it. McCain likes to fight, and he feeds off of adventure and uncertainty. He isn’t so much a maverick as a man constantly at war with the last version of himself. If his scenario now is partially of his own making—he inflamed the dyspeptic right just enough to draw himself a viable Republican challenger and cozied up to the dyspeptic right just enough draw himself a viable Democratic challenger—one wonders if this two-front war wasn’t on some level what he wanted. McCain, restless, set himself up for the re-election of his life, and he got it. He’ll never allow himself to retire. And if someone wants to retire him, it’s going to be a fight.

*Update, July 11, 2016: This paragraph has been updated to include comments from the Kirkpatrick campaign received after the publication of the article. (Return.)