The Hillary Clinton Doctrine

Her response to the massacre in Orlando reveals the type of commander in chief she would be.

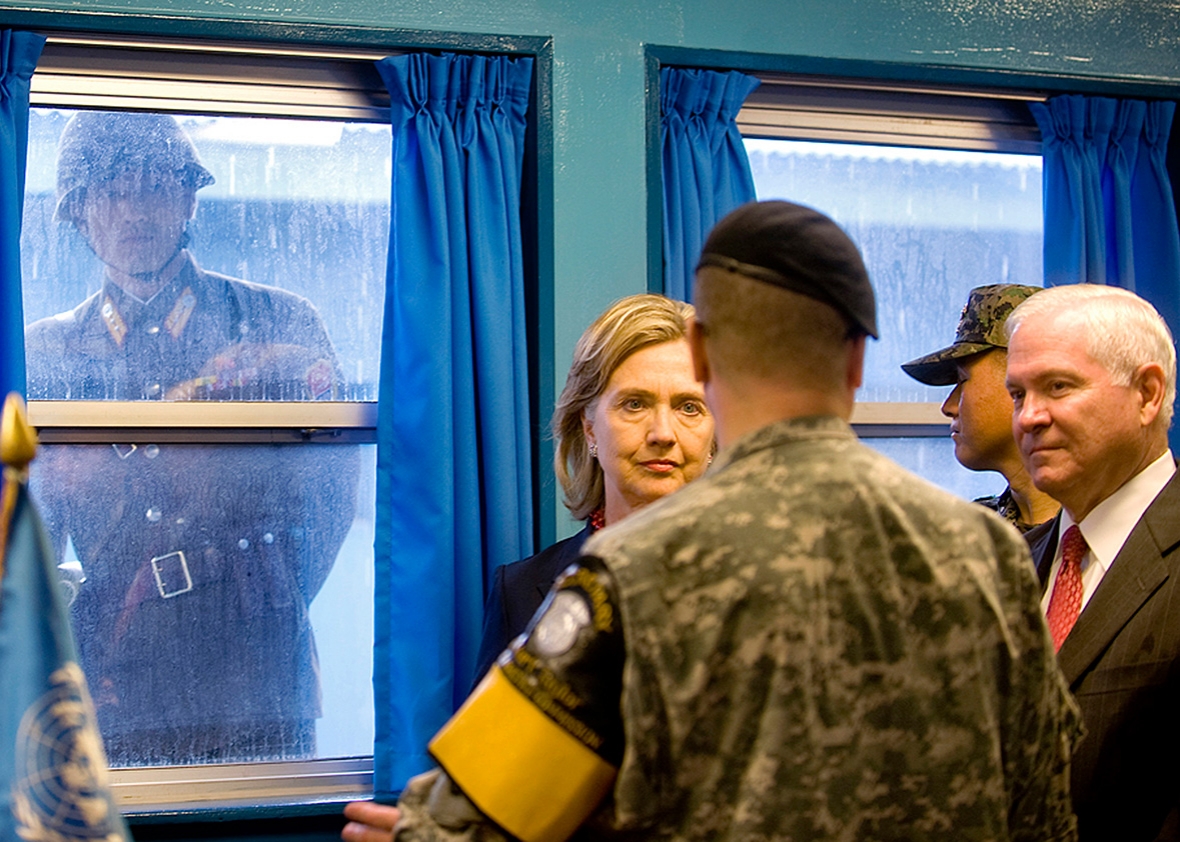

Noel Celis/AFP/Getty Images

With last week’s massacre in Orlando, Florida, the dread of terrorism and the anxiety of national security threats across the unstable globe broke through to the surface of our grim-enough electoral politics. The mass shooting also offered a preview of how the two parties’ presumptive candidates might handle a crisis.

The Republican, Donald Trump, proved himself an empty suit with a loud mouth, a set of dangerously shallow ideas, and an ego enormous enough to mistake them for wisdom. Hillary Clinton delivered a very different sort of speech. She was measured and thoughtful, unifying in places and aggressive in others, scrupulous about getting the analysis and the action right. You might call it a “presidential” address.

But what kind of president—what kind of commander in chief—did it suggest she might be, and how did it align with her long-standing positions on national security issues? How would her approach differ from the legacy of Barack Obama or the specter of Trump? How would those differences—not just in general rhetoric but in specific actions—shape American policies and the world they touch? Can one detect in her response to Orlando the outlines of a “Hillary Clinton doctrine”?

The widespread wisdom is that Clinton is a hawk. A recent headline in the New York Times Magazine blared, “How Hillary Clinton Became a Hawk,” as if the question of whether she is one had long ago been settled. But there are many species of hawks. What kind is she? Compared with her predecessor and her rival, will Hillary’s brand of hawkishness make us safer or less secure—raise or reduce the odds of plunging us into war?

And are these the right questions, or in any case the only ones, to ask? During one of her first briefings on China as secretary of state, Clinton asked, to the surprise of everyone in the room, highly detailed questions about several dam projects that Beijing had begun—referring to them by name—and wanted to know how neighboring India was reacting to them. “She understood that water resources were a national-security issue in the region,” the briefer recalls.

It was a small moment, but it reveals something important about how Clinton sees the world, beyond the hawk-dove binary. It suggests that, in much the same way she sees domestic policy as a series of interlocking problems, Clinton takes a more expansive view than most hawks (or doves) of what “national security” entails.

* * *

Hillary’s hawkish reputation is not undeserved. In the high-level debates over war and peace in Obama’s first term, when she served as secretary of state, Clinton almost always aligned herself with Secretary of Defense Robert Gates and his generals. She supported their case for sending 40,000 more troops to Afghanistan (Obama reluctantly approved 30,000 and then only with a pullout-date attached). She advocated keeping 10,000 troops in Iraq (Obama decided to bring them all home, in part because an agreement signed by George W. Bush required a total withdrawal). She sided with Gen. David Petraeus’ plan to arm “moderate” rebels in Syria (Obama rejected the idea, concluding it would have little effect on Bashar al-Assad’s regime or much else).

The only issue on which Clinton parted ways with the Pentagon was Libya, and in that case, she was more hawkish: she favored armed intervention to help resistance fighters who wound up toppling Muammar Qaddafi, while Gates and the top brass opposed getting involved.

Yet in her time as secretary, Clinton also took positions anathema to most hawks. She launched the “reset” with Russia (which accomplished a great deal, in nuclear arms-reduction and counterterrorism policies, until Vladimir Putin resumed control of the Kremlin). She was a champion of international women’s rights and children’s welfare, seeing these causes as vital for development, diplomacy, and global stability. She grasped the gravity of climate change earlier than most senior officials.

Even in her support for sending arms to Syrian rebels, one of her more conventionally hawkish positions, she opposed still more aggressive proposals to deploy tens of thousands of U.S. troops as an occupying force. And while she called for a no-fly zone to protect Syrian civilians, she linked the proposal to consultations with Russia, in order to minimize the risks of escalating conflict. (By contrast, some Republican presidential candidates who supported a no-fly zone salivated at the prospect of shooting down a Russian combat plane.) Similarly, on Libya, she called for armed intervention by a coalition, not by the United States alone. (Like Obama, she accepted assurances from NATO allies, especially France and Italy, that they would take the lead on reconstruction and “stability operations” after the fighting stopped—assurances that proved hollow.)

It’s hard to predict how Hillary Clinton will act or make decisions when she’s the one who’s alone in the Oval Office. The calculations of a senator, or the arguments of a cabinet officer, are different from the deliberations of a commander-in-chief. Still, judging from the long record of her votes and recommendations, it’s fair to say that she is more hawkish than Obama—but less hawkish than, say, John McCain, Lindsey Graham, the neo-cons who surrounded President Bush, or nearly all the Republicans who ran for president this year, including Trump. Her stance lies somewhere in between the poles, though, in her case, that’s not the same as saying she’s middle-of-the-road.

“She’s not very shy about using military power,” says Kurt Campbell, her former assistant secretary of state for East Asian affairs, now chairman and CEO of the Asia Group. “Some Democrats talk about using the military as a last resort. That’s not a natural way for her to think.” To Clinton, military force is but one of several tools of national power, and her mode of thinking, he says, involves “welding or integrating all of them together.”

A hallmark of President Obama’s thinking, dating back at least to his 2009 Nobel address, has been an acknowledgment of the limits of American power, especially in the post–Cold War era of global fragmentation. By contrast, Campbell says of Clinton, “The idea of ‘limits of American power’—that’s not in her. She was not humble about American power. She was always about leadership, took it as a given and a guiding star.”

Another former State Department official who worked with Clinton says, “She is inclined to take action—not necessarily military action, but she believes American inaction can leave a power vacuum, which could make us less safe in the long run.”

This is a key distinction between Obama and Clinton. Obama’s recognition of the limits of power, and his reluctance to act just for the sake of acting, has kept the nation from doing (as he put it) “stupid shit.” But this trait has also sometimes made him appear ambivalent, an apt pose for a scholar-statesman but riskily indecisive for a president. Clinton’s confidence in American power may make her look more resolute as president—but it may also lead the nation more determinedly into war.

* * *

Reuters

Clinton was born in 1947, at the dawn of what Time magazine heralded as “the American Century,” and she has long adhered to its assumptions about America’s central role in world affairs. Many of her contemporaries, as they came of age, were seared by the Vietnam War and emerged more skeptical about U.S. military power—and U.S. military advisers. But if Vietnam planted seeds of fundamental doubt in Hillary Clinton’s mind, she hasn’t let them show. Her views seem to have been shaped more by experiences in her husband’s presidency—especially his regret at not acting to stop the genocide in Rwanda and his redemptive decision to act, with a combination of airstrikes and firm diplomacy, to protect Kosovo from the savagery of Serbian President Slobodan Milosevic.

In his new book, Alter Egos: Hillary Clinton, Barack Obama, and the Twilight Struggle Over American Power, Mark Landler, a New York Times reporter, tells a story about the 2010 incident in which North Korea torpedoed a South Korean navy vessel, killing 46 sailors onboard. State and Defense Department officials devised a plan to send an aircraft carrier into coastal waters just east of North Korea, as a show of force. But the top U.S. admiral in the Pacific suggested that the carrier be rerouted, more aggressively, into the Yellow Sea, between North Korea and China. In the ensuing debate, Clinton supported the admiral, saying, “We’ve got to run it up the gut!” (Obama rejected the idea, in part because the mission was already in progress and, as he put it, extending the football metaphor, “I don’t call audibles with aircraft carriers.”)

Russia’s seizure of Crimea and a swath of eastern Ukraine occurred during Obama’s second term, after Clinton had left Foggy Bottom. But during the Q&A section of a speech at the Brookings Institution in September, Clinton said, “I am in the category of people who wanted us to do more in response” to Russia’s moves. Though acknowledging that the economic sanctions, which Obama coordinated with Western Europe, may “have had some impact” on Russian behavior, she said that the West “had to up the cost” to Russia and “to put more pressure on Putin,” noting that his objective was “to stymie and to confront and to undermine American power”—not just in Eastern Europe but “whenever and wherever [he] can.”

Obama’s logic, in declining to send Ukraine offensive arms, was that Putin would outplay us in that realm. Russia has a far greater strategic interest in Ukraine and could match or exceed our efforts very quickly, since the two countries share not just a long history but a long border. Better, Obama decided, to supply Ukraine with defensive military equipment, to share intelligence, and to focus more sharply on economic sanctions, where the West had an advantage over Russia (and where Obama has done a better-than-expected job of keeping the Western European nations onboard).

More recently, in her speech in Cleveland on June 13, the day after the Orlando shootings, Clinton first noted that not all the facts were yet known about the shooter, Omar Mateen (was he inspired by ISIS or a troubled, violent homophobe who used jihadist social media as an excuse to vent his self-hatred?), and she invoked the fundamental unity and tolerance of American society. Then she laid out her plan for defeating ISIS. It involved “ramping up the air campaign” in Syria and Iraq, “accelerating support” for Arab and Kurdish soldiers on the ground, pressing ahead with the diplomatic efforts to settle sectarian political divisions, and “pushing our partners in the region to do even more,” not least pressuring the Saudis, Qataris, and Kuwaitis to stop funding extremist organizations. At home, she called for an “intelligence surge,” upping the budgets of intelligence and law enforcement agencies, improving their coordination on a local and federal level, working with Silicon Valley to track and analyze jihadist recruiters on social media networks, and working with responsible leaders in Muslim neighborhoods (rather than alienating them by suggesting—as Trump did, in his speech on the same day—that all American Muslims are somehow complicit in the actions of extremists).

Some of these proposals are new, especially the “intelligence surge,” and seem tailored to the evolving domestic threats. It’s true, as Politico recently reported, that the FBI has enough agents to track just 48 suspected terrorists in the U.S., 24/7, at any one time. But it may also be true that, in order to find and relentlessly pursue possible “lone-wolf” terrorists (those with no direct connections to jihadist organizations), the FBI would have to change its nature from a law enforcement bureau to a domestic intelligence agency, with broad powers going beyond the restrictions of prosecutorial probes. Is that a path we want to go down? Does Clinton want to pave that path? It’s unclear.

As for the military and diplomatic aspects of her plan, these are things Obama has been doing for some time. (I asked some of Clinton’s advisers to clarify what she meant by “ramping up the air campaign” and “accelerating support” for ground forces—where, by how much, to what end?—but responses were vague.) The fact is, nobody quite knows how to deal with an organization like ISIS in a region like the modern Middle East, where the jihadists’ most natural and most powerful enemies are unable to fight together because they fear and loathe one another more than they fear and loathe ISIS.

Which leads to a larger point—that, in their basic policies and outlook on the world, the differences between Obama and Clinton are relatively minor. Even Mark Landler, whose book chronicles their competing views on military power, acknowledges in his first chapter that, during her time as secretary of state, she and Obama “agreed more than they disagreed. Both preferred diplomacy to brute force. Both shunned the unilateralism of the Bush years. Both are lawyers committed to preserving the rules-based order that the United States put in place after 1945.” Their disputes, he writes, stemmed mainly from their “very different instincts for how to save” this post-WWII order as it has fractured in the aftermath of the Cold War.

Their common ground is highlighted by their common, stark contrast with Donald Trump. The “rules-based order” that Clinton and Obama both cherish holds no interest for Trump; nor does he seem to know anything about its history, its institutions, or its value to American security.

Trump has said that, as president, he would torture suspected terrorists and murder their families, reflecting an indifference or hostility to international law. His idea for beating ISIS is to “bomb the shit out of them” (not realizing, or perhaps caring, that ISIS fighters live among innocent civilians, whose killing by U.S. air power would rouse their friends and relatives into alliance with the jihadists), to ban all Muslims from entering our borders (unaware that this would energize jihadist propaganda), and—in his post-Orlando speech—to throw Muslim American citizens in jail if they don’t report their suspicious neighbors. Trump dismisses NATO as “obsolete” and says, with a shrug, that he’d abandon allies in Europe and Asia if they didn’t pony up more money for their defenses, even if our withdrawal would prompt them to develop their own nuclear arsenals. Yet he also believes that, all on his own, he can negotiate “great deals”—of what sort, he’s never specified—with Putin and North Korea’s Kim Jong-un. (He strikes a peculiar, if clueless, affinity with authoritarian leaders.)

Trump is neither hawk nor dove, but rather some vague mutant hybrid—part isolationist, part international hoodlum, at once a byproduct and aggravator of the era’s teeming resentment, rage, and incipient global anarchy.

By contrast, Clinton is less a hawk or a dove than a traditionalist, and a cautious one at that. Amid the exuberance of the Arab Spring and the street protests in Cairo, she advised against cutting off Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak, fearing that his successors might be worse. Had she remained secretary of state in Obama’s second term, she probably wouldn’t have stretched out the ill-fated Israeli-Palestinian talks for as long as John Kerry did; yet she might also not have stuck so long with the Iran nuclear talks, which resulted in a remarkable deal that she now fully supports. On the occasions when she called for the use of force, she usually did so in the context of an alliance or coalition, and for the purpose of upholding a regional order rather than toppling one.

Dusan Vranic/Pool/Reuters

Her vote as a senator in 2002, authorizing President Bush to invade Iraq, is of course the action that most vividly emblazoned her image as a hawk. It may also have cost her the Democratic contest in 2008 (to Obama, who had spoken out against the war), and it animated much of the support for Sen. Bernie Sanders in the 2016 primaries. (Her Iraq vote was the only example Sanders cited—and cited repeatedly—of Clinton’s “poor judgment.”)

Early on in this year’s race for the Democratic nomination, during a town hall debate in New Hampshire, Clinton explained that Bush had made a “very explicit appeal,” pledging to use the Senate’s authorization as “leverage” to prod Saddam Hussein into readmitting U.S. inspectors, so they could resume their mission of verifying whether Iraq was building weapons of mass destruction. In other words, she claimed that she voted the way she did in the interests of diplomacy; the problem, she said, was that Bush went back on his word.

The transcript of the 2002 Senate debate reveals that Clinton was telling the truth at the 2016 town hall: This was the rationale she gave, in a long, seemingly anguished speech, for supporting the resolution. (It was also the reason many other Democratic senators—including John Kerry and Joe Biden, whose subsequent careers did not suffer—also gave in authorizing an invasion.) Still, Clinton’s logic does not explain why she didn’t oppose the war after the invasion got under way (though she did later vote against the troop-surge), or why she never read the full pre-invasion intelligence report (which included some agencies’ doubts about whether Iraq actually possessed chemical, biological, or nuclear weapons), or why she took so long—not until very late in the 2008 campaign—to admit that her vote had been a mistake.

She has a genuinely strategic mind. Just as she sees the linkages between development and stability, water resources and national security, she understands that diplomatic pursuits require leverage and that leverage often entails a display (with an implied threat) of force. But Iraq stands as a case in point where strategic thinking of this sort can overcomplicate matters. Even aside from the errors in her assumptions (that Iraq had a WMD program and that Bush was really interested in using the Senate vote as a lever for diplomacy), she downplayed—perhaps evaded—the flip side of her calculations: What if Bush had tried to persuade Saddam to readmit the inspectors and Saddam still refused? Would that have been reason enough to invade? Given its risks and America’s competing priorities in the region, was war the wise course? Her vote—and her long delay in expressing regret for the vote—suggests that she thought it was. As president, would she exert leverage against some other nations, in an attempt to prod their leaders to accept her demands or alter their behavior—and take the slippery slide to war if they don’t?

Then again, it’s false to suggest that Clinton has a consistent tendency to swerve onto risky paths. She may not be shy about using force, as Kurt Campbell says, but that doesn’t mean she’s gung-ho to do so.

For instance, when it came to drone strikes, the Obama administration’s preferred instrument of military power, she was sometimes more cautious than the president, less prone to favor an attack. As a matter of protocol, when the CIA proposes secret drone strikes in a foreign country, the State Department is given a chance to weigh in. On the occasions when the U.S. ambassador in a country (usually Pakistan) advised that a strike’s location, timing or target would have politically disruptive consequences, Clinton opposed the attack. When David Petraeus was CIA director, he ceded to Clinton’s judgment in those cases and called the strike off. Petraeus’ predecessor, Leon Panetta, always ignored her objections, once, in a National Security Council meeting, even growling at her, “I don’t work for you!” (Obama, at least in his first term, almost always sided with the CIA.)*

Cherie Cullen/DOD via Getty Images

Finally, there’s the case of Obama’s most dramatic decision: the very high-level debate over whether to order the raid on Osama Bin Laden’s compound in Pakistan. It was a question racked with dilemmas and uncertainties; the intelligence agencies were divided over whether Bin Laden was really even there. Clinton filled a legal pad, listing the many pros and cons of acting or not acting. She came down in favor of the raid, but just barely. Her position wasn’t that of an impetuous, adventurous hawk; it was precisely the same position as Obama’s.

The president and his former secretary of state are also speaking in harmony, if not unison, in the wake of Orlando. Notwithstanding her tendency to do more, faster, stronger, the approach she’s prescribed is very similar to his. It’s an approach based on analyzing the facts, understanding the vital role of allies (at home and abroad), and grasping the motives of terrorist groups, what makes their recruitment drives appealing, and what responses from the West might intensify or slacken their appeal. The difference between Clinton and Trump is the same as the difference between Obama and Trump: It’s the difference between someone who has a sophisticated knowledge of international relations (granting that this doesn’t always lead to the most successful policies) and someone who has no knowledge whatsoever.

As one of her assistants in the State Department puts it, “The differences between Obama and Clinton are real, but they’re not huge. She’s on the slightly tougher side of the spectrum.” Call it the Obama-plus-a-bit doctrine.

*Correction, June 19, 2016: The article originally misstated that Leon Panetta suceeded Gen. David Petraeus as CIA director. Petraeus served after Panetta. (Return.)