Bernie’s Way

The Vermont senator doesn’t want to bring Republicans and Democrats together. He means to tear it all down.

The students of Concord High School had just finished a week of exams but remained in school for an afternoon assembly. The New Hampshire school’s guest speaker was 74-year-old Sen. Bernie Sanders. Rather than groaning about having to stick around for another couple of hours, though, the students were elated.

“It’s so funny, we’ve been bringing some candidates in throughout the year, and everyone’s really excited and been asking good questions and having a great time,” said Chrigus Boezeman, a social studies teacher doubling effectively as Sanders’ hype man on this Friday in January, a few weeks before the New Hampshire primary. “And everyone’s saying to me, ‘Mr. Boezeman, gosh, it’s really great that you’re having all of these candidates come in. But … do you think Mr. Sanders can come in?’ ” The students, who were about to get the candidate they’d wanted to see for months, whooped with approval, breaking out into periodic chants of “BER-NIE, BER-NIE!” while they waited.

A high school student body is never the most voter-rich crowd to address on a cramped two-day swing through a crucial primary state. But for Sanders, whose campaign message rests on expanding voters’ realm of the possible in an age of frustratingly static politics, the opportunity to mold impressionable young minds was too good to pass up. These are the same sort of minds that then-Sen. Barack Obama, the last candidate to successfully inspire voters to look beyond the stale politics of the day and imagine something better, captivated in 2008.

“People sometimes think, and the media picks up on this: Well, Washington’s very bitter, very dysfunctional, and the reason is Democrats and Republicans can’t get along,” Sanders told the assembled students. “That is not the issue at all.”

“It’s not a question of personalities,” he continued. “It is a question of philosophy. Some of my colleagues believe that we should cut, or end, Social Security and Medicare and Medicaid. That government should not be involved in those areas. That, essentially, as a nation, we are out there on our own. Others believe that as American citizens that we are entitled to rights.” He mentioned, as just one example, “the right of Colleen”—a Concord High School student who had told Sanders that she’s facing the prospect of $80,000 in college debt even though she has “never gotten a B in [her] life”—“and millions of other young people to get a college education if they have the ability to do so, regardless of the income of their family.” Or the right to have health care “because they are human beings.”

The students met this with rapturous applause. But how would he, as another student went on to ask him, “compromise with the Republicans in the Congress to make those things happen?”

Sanders first mentioned the list of bills he has worked with Republicans to pass, namely the Veterans Affairs reform bill he successfully marshaled through Congress alongside Sen. John McCain. He ticked off these accomplishments in a flat, perfunctory manner—the practical items his advisers insist he list before returning to the theoretical battlefield he prefers.

“But there is a more important question,” he continued, “and that is that the Congress must begin to do the work that the American middle class and working families want them to do, rather than just do the bidding of wealthy campaign contributors.”

Sanders is aware of the impracticability of his policy platform in today’s political environment. “If I am sitting down negotiating with, say, the speaker of the House, a Republican,” he gave as an example, “and 80 percent of young people don’t vote, and 50 or 60 percent of the American people don’t vote, and I say, ‘You know what? I think we should make public colleges and universities tuition free, and I think we should pay for that based on a tax on Wall Street speculation,’ he will look me in the eye and say, ‘Are you kidding? Not in a million years.’ ”

Like Sen. Barack Obama—the “change” candidate who preceded him—Sanders is riding a wave of energy among young people. Sanders holds a national 2-to-1 advantage against Hillary Clinton in support among voters under 45 years old, according to a New York Times/CBS poll in January, and he won voters age 17 to 29 by 70 percentage points in the Iowa caucuses. Like Obama, he’s soared not just by virtue of his specific policy proposals, but also by offering a theory for how to bust through the fundamental problem: the seemingly intractable gridlock of a broken political system that, when it does work, only works on behalf of the wealthy. And like Obama, Sanders’ rival is Clinton, a scarred veteran who takes politics-as-trench-warfare as a given and considers candidacies that promise to shift politics toward a sunnier, post-polarization paradigm to be fundamentally naïve.

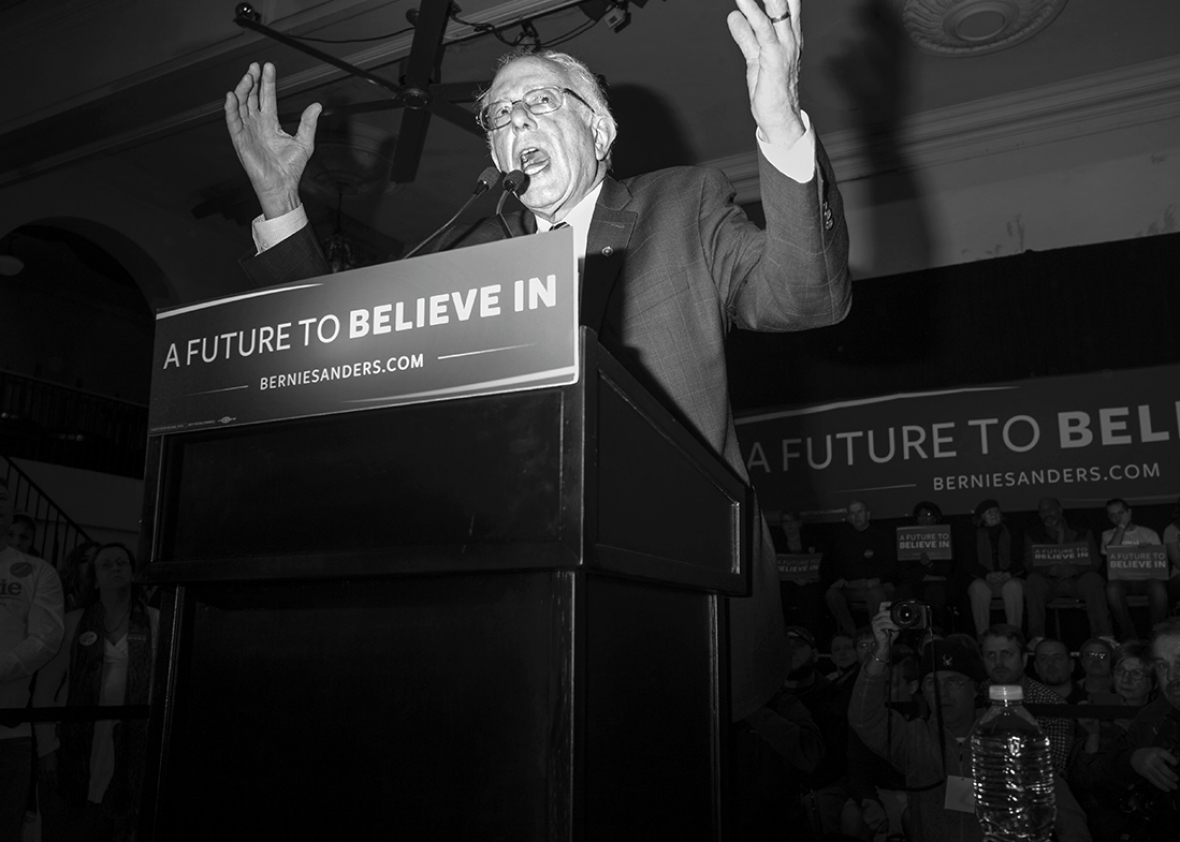

Danny Wilcox Frazier/VII

“But if, on that very day, as an example,” he continued, “a million young people march in on Washington to say exactly what Colleen said a few moments ago, that all of our young people who have the ability deserve to get a college education regardless of the income of their families, suddenly, that gentleman will look out the window and say, ‘Well, Mr. President, let’s sit down and talk about how we can address this serious problem.’ ” Sanders, who on the trail is far more savvy than his caricature as a blunt, screeching old leftist, picked the right issue from his platform to connect with high school students. They cheered.

But Bernie Sanders is not Barack Obama. Sanders’ theory for fixing the broken political system is post-Obama, taking into consideration Obama’s failure while posing a new answer. Sanders doesn’t talk about bringing the two sides together through the sheer force of his fetching personality. He doesn’t really speak of Democrats and Republicans as the two sides. He campaigns on a promise to turn the whole thing upside down, to create a grassroots “political revolution” that will give him the mandate to bring working- and middle-class people together to overwhelm the “billionaire class” into submission. He doesn’t want to heal, he wants to upend—and his voters, even after witnessing all of Obama’s failures to bring the country together in his own way, love Bernie for it.

* * *

Obama’s theory of change in 2008 was not as ludicrous at the time as it seems in retrospect. But it did fail.

The junior senator from Illinois blamed much of the dysfunction that materialized under Bill Clinton and George W. Bush on a partisan “bickering” that had taken on a life of its own, to everyone’s detriment. “We have come to be consumed by a 24-hour, slash-and-burn, negative-ad, bickering, small-minded politics that does not move us forward,” he said in late December 2006, shortly before announcing his candidacy. “Sometimes one side is up and the other side is down. But there’s no sense that they are coming together in a common-sense, practical, non-ideological way to solve the problems that we face.”

The solution to that, as his campaign message of “hope and change” over the next two years implied, was the election of Barack Obama: a post-partisan figure who would empathetically and judiciously take into consideration all points of view to determine a way of moving forward on which all sides could agree. His election would signal to entrenched partisan actors that playtime was over. “I want us to rediscover our bonds to each other and to get out of this constant petty bickering that’s come to characterize our politics,” he said in a characteristic interview with Rolling Stone in mid-2008.

There was reason to believe in 2008 that on policy grounds, political differences were relatively bridgeable, and a compelling figure like Obama could get Democrats and Republicans in a room to ice the deal. Both President George W. Bush and Obama’s Republican general election opponent, Sen. John McCain, by then accepted the science of anthropogenic climate change and supported plans to combat it—McCain perhaps a bit more seriously than Bush. Both Democrats and Republicans were warming to tackling universal health care reform for the first time since President Bill Clinton’s first term. Both McCain and Obama stated their desire to close the prison at Guantanamo Bay, something that even the Bush administration had considered near its end before leaving it to its successor.

When President Obama took office, he made the overtures. During his first major legislative effort as president, the “stimulus,” he visited Capitol Hill to meet privately with House Republicans, where he offered to throw more tax cuts into the package to secure their votes. He tasked a bipartisan gang of senators, whose Republican members at first seemed willing partners, with drafting compromise health care reform legislation. He did the same on climate change legislation.

What Obama underestimated was how viciously the GOP would snap from a governing party to an opposition party.

Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell instructed his body to use the filibuster to block as many of Obama’s major legislative gains as possible—and, once Democrats secured 60 votes in the Senate, to keep Republican “fingerprints” off of whatever knotty legislating the supermajority worked toward. Though Obama offered the stimulus with more tax cuts than Democrats advised, and approached both health care and climate change legislation from centrist, market-oriented perspectives, congressional Republicans refused to bite. When voters rewarded Republicans in the 2010 congressional elections with a landslide—in no small part due to the fact that the disaffected young voters in Obama’s coalition didn’t turn out to vote—that was the whole ball game. “Bickering” won. Since the 2010 elections, it’s required a Herculean effort simply to keep the government open, let alone move any significant bipartisan reform legislation.

Among the 11th-hour tax and spending deals that the Obama administration has gone on to make with the Republicans, and which few people on either side really seem to like, was a 2010 lame-duck session deal that temporarily extended tax breaks for the rich. The agreement reauthorized the 2001 Bush marginal tax cuts for the top two income brackets while raising the estate tax exemption to a historically high $5 million. Liberals were furious at the Obama administration for welching on one of the president’s top campaign promises: letting the 10-year, budget-busting Bush tax cuts for the wealthy sunset on schedule.

Sanders, then still in his first term, took to the Senate floor to lambast the agreement for more than 8½ hours. “The Speech,” as it would come to be known (and published as a stand-alone book under that title), went beyond the mere exercise of calling out President Obama for selling out liberals. Sanders conceded that “maybe” Obama was right when he argued that this was the best deal that he could have struck with the Republicans. And that was the problem: that this was the best anyone could hope for in a fundamentally corrupted political process that exists to serve the wealthy and powerful interests. It was the process that needed to be changed, then, and it needed to be done from the bottom up—not by simply installing a new figure atop the system, who would be constricted in the same way, serving the same set of interests.

Danny Wilcox Frazier/VII

“It is important to put the agreement the president struck with Republicans in a broader context,” he said. “We can’t just look at the agreement unto itself. We have to look at it within the context of what is going on in the country today, both economically and politically. I think I speak for millions of Americans: There is a war going on in this country.

“I am talking about a war being waged by some of the wealthiest and most powerful people against working families, against the disappearing and shrinking middle class of our country,” he continued. “The billionaires of America are on the warpath. They want more and more and more.”

He described the government’s inability to serve the interest of broad swaths of the country on a far deeper level than Democratic and Republican legislators consuming themselves with partisan “bickering.” He didn’t really concern himself with partisanship much at all—as an independent senator who caucused with Democrats might not. He reoriented the battlefield from one that was left versus right to one that was the wealthy versus the working and middle classes. Like Obama, he imagined there was a large, cross-partisan consensus for certain changes; unlike Obama, he portrayed the obstacle to realizing this consensus as not lawmakers’ own petty gamesmanship, but as an aggressive “billionaire class” waging warfare from the top down.

* * *

Most Democratic and Republican political operatives consider Sanders an unelectable gadfly who would hand the White House to Republicans if he were the Democratic nominee for president. But there is one classic campaigners’ trait that the professionals admire, to the point of wonder, in Sanders: his ability to stay “on message.”

Sanders’ campaign message is nearly identical to the message he explained at length in his 2010 speech—except now he has even more eye-popping income inequality and campaign finance statistics to work with. The way he frames his candidacy now, in a way that is intended to differentiate himself from Clinton, is as a break from the “establishment politics and establishment economics” that are no match for the “crisis” facing the country.

“I’m running for president of the United States not because I think my Democratic opponents are terrible human beings—that they’re not smart or they’re not concerned,” he said at the beginning of a speech before college students at South New Hampshire University on Jan. 21. “I’m running for president because I think it is just too late for establishment politics and establishment economics.”

By establishment politics, he means the practice of electing representatives to the White House or Congress who, no matter how personally talented they are, become overwhelmed by the strength of existing, wealthy special interests. In other words, a political system that expects change to occur from the top down. By establishment economics, he means a consensus that relies too much on outsourcing economic prerogatives to the private sector without maximizing the strength of the federal government to arrive at a more just distribution of wealth.

The political fix, per Sanders’ thinking, gives way to the economic fix. Chief on that list of political fixes is reining in a campaign finance system run amok following the Supreme Court’s Citizens United decision in 2010.

“Do you know who the Koch brothers are, guys?” Sanders, playing professor again at SNHU, asked the youthful crowd. “The Koch brothers are the second wealthiest family in America … they are an extreme right-wing family that wants to not cut Social Security—they want to end Social Security and Medicare and Medicaid. They want to abolish the concept of the minimum wage. They want to end all campaign finance regulations so billionaires can give money directly to candidates, making them their own employees.

“Do you think you beat them just by electing a president?” he continued. “We need a mass movement of people who stand up and fight back, and that’s what this campaign is about.”

According to Bernie, if you weaken the grip that the “billionaire class” holds on presidential and congressional candidates, and if ordinary people both show up to vote and advocate tirelessly for their beliefs, then that’s how you break the stalemate in Washington. There isn’t much space in this pitch for the usual fare about ushering congressional Republicans and Democrats into a room to “roll up their sleeves” and hash out a deal. Once the political terrain is shifted, these actors will necessarily find themselves in the room rushing to work on the people’s behalf, so magnificent will be the working- and middle-class pressure on them to act.

Sanders’ theory implies that once the masses have banded together to overpower the political prowess of billionaires, corporate interests, and “establishment economics,” what they will demand is a series of leftist reforms like single-payer health care, free public higher education, a federally mandated living wage, breaking up the too-big-to-fail banks, and a shift away from a hydrocarbon-based energy system. But it does not entertain the idea that once the palace has been raided and billionaires are sent fleeing, a significant chunk of working and middle-class people might still disagree with his policy proposals.

“We know what has to be done [on climate change], and now’s the time to do it,” he said at SNHU in response, sort of, to a question about the gas leak at the Aliso Canyon Natural Gas Storage Facility in California. “We have got to break our dependency on fossil fuels.” In an effort to “connect the dots,” he asked the crowd how the “corrupt campaign finance system” relates to the lack of action of climate change, or the refusal to turn away from fossil fuels.

“A lot of the Republican candidates are funded by the oil industry?” someone offered.

“Exactly,” Sanders said approvingly. “It’s not very hard to understand.”

The campaign donations don’t hurt. But is it the whole story? People—yes, including many working and middle-class people—enjoy cheap fossil fuels, even if they’re aware that it’s poor for the environment. And the oil and gas industry is a major employer: Consider the 2.7 percent unemployment rate for December in North Dakota, the postcard state for the fracking boom. If congressmen or senators representing North Dakota—or any of the other states enjoying great wealth from the presence of oil, gas, or other fossil fuels under their feet—are looking at a bill to move away from those sources of energy, their opposition isn’t entirely the product of a peek at their campaign coffers. It’s about maintaining and creating working and middle-class jobs for the people they represent, however myopically. For all the control that billionaires and corporate special interests do exert on the political system, the largest special interest is still millions and millions of people who like the securities that they do have and reject the root-and-branch changes a candidate like Sanders proposes.

As Obama’s example has shown, a candidate can promise systemic change, but if the theory for achieving it isn’t airtight—and it rarely is—the disappointment of unmet expectations can be crushing to those who allow themselves to be captivated. That appeal to caution and realism is even more central to Sanders’ chief Democratic rival now than it was Obama’s chief Democratic rival in 2008.

Hillary Clinton has limited patience for opponents who speak in terms of political sea changes. She would have hoped that Obama’s inability to bring about a paradigm shift away from gridlocked politics would resign voters to a candidate who’s only ever promised the grind. But here we are again.

Clinton accepts straightforwardly that the battle in the country is between Democrats and Republicans who believe in different things. There is no realignment coming. You cannot disappear powerful special interests, but you can manage them. The important thing is to elect a Democrat—namely, Clinton. Sanders spends little time talking about Democrats, Republicans, or even himself. He speaks in broad, start-from-scratch terms about, say, “creating an economy” that works better than the current one. Clinton speaks of building on what’s already been built over the past seven years and keeping the White House out of Republicans’ hands. Sanders’ economic history of the last 25 years is simple and straightforward: The rich and powerful have gotten richer and more powerful at the expense of everyone else. Clinton’s pitch is that the economy has either been good or bad depending on which party was in control of the presidency.

“[Bill Clinton] inherited a recession,” Clinton said at a Jan. 22 town hall in Manchester, New Hampshire, to a standing-room crowd. “He inherited a quadrupling of our debt in the prior 12 years. … At the end of eight years, we had 23 million new jobs, but most importantly, incomes went up for everybody.”

“Well, unfortunately, along came George W. Bush,” she continued. Boo! “We had a balanced budget and a surplus. We had an economy that had created rising incomes. And they want back to the same old stuff: cut taxes on the wealthy, get out of the way of corporations … and you know what happened: the worst financial crisis since the Great Depression.”

Obama had “done nothing to create the mess he inherited, but it was up to him to fix it,” she said. “And I don’t think he gets the credit he deserves.”

Obama himself, who once envisioned entering the presidency with a mandate for broad change that would translate into a “big bang” of bipartisan legislation on health care, climate change, and financial reform, appears to have gravitated to Clinton’s view of eternal partisan struggle. “The truth is,” Obama told Politico in a recent interview, “in 2007 and 2008, sometimes my supporters and my staff, I think, got too huffy about what were legitimate questions she was raising” about his vision. Obama used to mock what he perceived to be the Clintonian focus on small-ball measures like school uniforms after their own top legislative items were stymied in 1994. Now he’d be lucky to move forward on something anywhere near as sweeping and comprehensive.

* * *

Bernie Sanders abhors those who look at politics as “stagnant.”

“There was once a time not so many years ago,” he told the students of Concord High School, “where people felt that someone, because the color of their skin was different than mine, that person should not have the right to vote. … It took a very, very long time, and a whole lot of people to say, ‘That is wrong.’ It took a change of consciousness.”

“So the first point I want to make to you,” Sanders leaned in, “and I want you to be thinking about it, is: How does change come?”

What powers Sanders and his campaign, even after Obama’s failure to move the country to a sounder political system, is a sense that what’s happening now is untenable. Both in terms of an economy killing all but the rich, and a political system of such dysfunction that its constitutional design has been called into review.

If there is a bipartisan strand of thinking that’s caught fire this cycle, it’s the idea that promises of bipartisan cooperation from the top down are the most unrealistic promises of all. Though the two parties are so gapingly far apart on policy that they’re not even addressing the same policy questions—one party feels that climate change is the greatest threat to world peace and security today, for example; the other is either agnostic or outright hostile to its very existence—their most surprisingly successful candidates are addressing the same structural question of tenability.

Sen. Ted Cruz offers a near mirror image of Sanders’ theory of change, promising to bludgeon the establishment “Washington cartel” into submission by appealing to the vast grassroots movement he’s sought to build. Donald Trump speaks of “dealmaking,” but his vision has less to do with ushering bipartisan cooperation than with him wielding his own personal strength against the “losers” who oversee the current, broken system.

Pundits, operatives, and other in-the-know types expected more prosaic candidates like Clinton and Jeb Bush to coast to their respective nominations as voters, having witnessed what awaits a president-elect who promised an epochal shift, settled for a more realistic view of the political process. But voters have resigned themselves to a competing realism: that a greater level of political audacity is in order, because what we have right now isn’t working.

Sanders’ proposed solution is a long shot, and it is not without its arguable premises. But the fact that he’s the one who’s most up-front about its difficulty is what gives his supporters the impression that his campaign is one worth joining. What Sanders knows, though, is that his own election or defeat in this primary cycle is a minor part in the movement he’s trying to create that needs to last for years and not just to spike during election seasons. That means insisting that people continue to think of big changes in their politics, not small ones—even if they’ve been burned before.