Unbuilt Highways

I-478 is a pretty remarkable road: It is, for one thing, the longest tunnel on the U.S. Interstate Highway System. It's also the longest subaqueous facility. But I-478 conceals its charms; driving on it, there is nothing—not a single red, white, and blue shield—to tell you that you are doing so.

This shy and retiring facility is the Brooklyn Battery Tunnel, connecting Brooklyn to Lower Manhattan. While it appears on maps, I-478 is not signposted (to avoid driver confusion with Brooklyn's nearby I-278, the story goes), and virtually never referred to by its federal designation.

I-478 is something of a phantom highway, and if you head north to the Manhattan Bridge, you can find a clue as to its origins: a bit of hanging roadbed in the median that simply comes to an end. This severed trunk is all that remains of the I-478 that never was: the Lower Manhattan Expressway.

The Lower Manhattan Expressway—dubbed "Lomex"—which would have coursed in eight-lane glory through the now-vibrant (and expensive) neighborhoods of Soho and Nolita, is one of the world's most famous unbuilt highways. The epic battle about whether it should be built is virtual mythology in New York City, pitting the sweeping interventions of Robert Moses against that savior of the street, Jane Jacobs, a conflict of networks against neighbors, a struggle over a road that was either essential to Gotham's 20th century survival or, in the words of Lewis Mumford, was "the first serious step in turning New York into Los Angeles." (Not thought to be a good thing.)

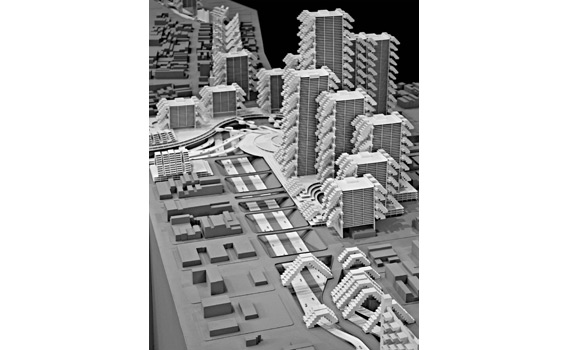

A recent exhibit * at New York's Cooper Union, Paul Rudolph: The Lower Manhattan Expressway—complete with an exhaustively recreated scale model * of the proposed road—provided an opportunity to consider the invisible (and sometimes visible) presence of this and other phantom highways in the world's cities. Existing merely as segments of many-tentacled schemes on faded planner's maps, they are more than historical oddities or visions of an alternate future. They're part of an ongoing dialogue about the meaning and possibilities of mobility in the world's cities: Would their host cities be better off if these highways been built? How should we balance the desire for mobility with the desire to create livable, meaningful urban spaces? Is there any room for the megaprojects of Rudolph in a city that now favors pocket parks and restriped bike lanes?

Here, then, is a memento mori to these phantom highways, a representative sampling of roads that were never built or that were built and later demolished. Their history helps us understand to what extent the car and the city can ever be reconciled.

Corrections, Dec. 27, 2010: This article originally referred to the Paul Rudolph exhibit at Cooper Union as ongoing. In fact, it had closed as of the publication of this piece. (Return to the corrected sentence.) The article also stated that the exhibition contained a full-scale model of the Lower Manhattan Expressway. The model was actually less than full-size. (Return to the corrected sentence.)