The Color of School Reform

After Hurricane Katrina, New Orleans fired its mostly black teacher corps. Now its charter schools are trying to convince black educators that there’s a place for them.

William Widmer/Slate

NEW ORLEANS—Throughout her first year at KIPP Central City Academy, Raven Foster heard the kind of compliment every educator loves to receive from students: that she was their favorite teacher. The reason, however, wasn’t because her kids loved her science class, or because they liked her sarcastic sense of humor, or because they appreciated her no-nonsense attitude. One after another, they told her they liked her because she’s black.

Foster knew she’d be one of just a few black teachers when she started working at this New Orleans charter school in 2012. While the overwhelming majority of the student body is black, nearly two-thirds of the teachers were white when she took the job. But her first year of teaching was hectic, filled with home visits, grueling lesson planning, and a schoolwide move to a brand new building. The racial makeup of the staff wasn’t a concern she had time for—until she realized that her kids were noticing it.

“I heard a student say, ‘Ms. Foster, I can’t get away with stuff with you because you’re black, but I can with this teacher because she’s white,’ ” she says.

Even innocuous interactions, like taking students to lunch or giving them rides home, came to be characterized by students racially. If a white teacher did something nice for a student, the student might muse, “Why isn’t the person that looks like me nice to me?” Foster says. “To me, that was them telling me, ‘I wish I had more.’ ”

What the students wanted more of was teachers who looked like them and came from a similar background, teachers who understood how they talked, behaved, and lived. And increasingly, Foster agreed: More teachers like her—black and from New Orleans—was exactly what schools like KIPP Central City Academy needed.

That realization has spread among charter school and school reform leaders nationwide in recent years as they have increasingly recognized that neglecting the racial composition of their ranks could stunt their attempt to reach and serve students of color. Charter school teachers, like the teaching profession nationally, are predominately white. And in post-Katrina New Orleans, they are more likely to be white than traditional schoolteachers are.

This new focus on recruiting minority teachers hasn’t met immediate success. Teach for America has signed up significantly more teachers of color, and charter networks around the country have kicked off similar recruiting campaigns. But the New Orleans experience shows how challenging the work can be: Charter leaders there still struggle to hire more black and local teachers—and to convince veteran teachers that they, too, are needed in the school-reform movement.

Before Hurricane Katrina, the New Orleans school system boasted a significantly higher share of black teachers than most urban districts. In 2003, just 15 percent of teachers in large cities across the country were black. In New Orleans, where nearly all students are black, that figure was 72 percent.

In the aftermath of Katrina, the school board fired the district’s thousands of teachers en masse as it reconstituted the system as one largely composed of charter schools. Many educators weren’t rehired; some left teaching, or the city, for good. Between 2004 and 2014, the percent of black teachers plunged from 71 percent to 49 percent. And far fewer teachers working in schools were raised in New Orleans—resulting, many say, in large cultural gaps between the teachers and their majority-black, native New Orleanian students. In recent years the proportion of black teachers in the city has stabilized, according to a report by Tulane University’s Education Research Alliance. But hiring rates are telling. Some years, nearly 70 percent of new teachers in the city are white.

After Hurricane Katrina struck in 2005, the proportion of white teachers in New Orleans rose sharply.

Source: Education Research Alliance for New Orleans, "Significant Changes in the New Orleans Teacher Workforce"

The proportion of inexperienced teachers also rose.

Source: Education Research Alliance for New Orleans, "Significant Changes in the New Orleans Teacher Workforce"

As did the proportion of teachers who completed their undergraduate degrees outside of New Orleans and Louisiana.

Source: Education Research Alliance for New Orleans, "Significant Changes in the New Orleans Teacher Workforce"

New Orleans and schools across the country know they need more teachers of color. So why is finding more instructors like Foster such a challenge?

* * *

William Widmer/Slate

KIPP Central City Academy opened in 2007, two years after the storm. Like many New Orleans charter schools, its founders recruited heavily among Teach for America corps members and recent alumni, a group that was, at the time, disproportionately white, young, and new to the city.

For the first four years, “the focus was on systems, systems, systems,” according to Alex Jarrell, a former TFA teacher originally from New York City who took over as Central City Academy’s principal in 2012 after working as a teacher there and in a neighboring parish. By systems, Jarrell meant meticulous rules and procedures that governed how students would learn, behave, and even move within the school. In the eyes of many charter school leaders, the race of the teachers who designed and enforced these systems didn’t matter as long as they were dedicated, consistent, and focused on constantly improving their teaching skills. White people founded a disproportionate number of the charter schools and, perhaps predictably, hired from within their own often predominantly white networks.

Over time test scores increased, on average, and graduation rates improved. But Jarrell says kids didn’t love their schools, which weren’t as deeply embedded in the community as their predecessors had been.

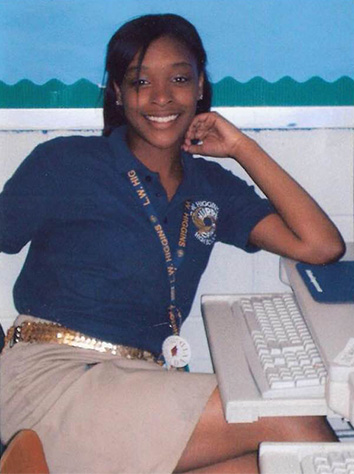

Jarrell had just taken over as principal in 2012 when Foster was hired, fresh out of nearby, historically black Xavier University of Louisiana. Foster grew up in New Orleans’ Westbank, a series of communities situated along the western bank of the Mississippi River.

Foster’s own education was rooted in the many school-based traditions that have historically helped define the educational experiences of black New Orleanians—activities such as marching band, baton twirling, football, and long-standing homecoming rivalries. At L.W. Higgins High School, Foster was taught by some of the same educators as her mother, also a Higgins alumna. But she says her childhood classrooms often lacked rigor and structure. Once, she recalls, “I remember walking into the room and [the teacher] had everything written on the board. We wrote everything on the board, and then class was over.”

Raven Foster

She also remembers spending middle school lunches roaming freely between the cafeteria, a concession stand, and the outdoors. That autonomy had upsides, helping her and her classmates mature, Foster says. She’s concerned it’s an opportunity lost to charter students bound by rules that govern their movement throughout the school day. “When you have less freedom, you want to break out of that structure so badly that you’re consistently finding ways to do so.”

Foster hadn’t originally planned to be a teacher. After Katrina ravaged the city during her sophomore year of high school, her family fled to Alabama, where she attended high school for more than a month before returning home. Her class had shrunk from about 500 students to 150. In 2008, she graduated and enrolled at Xavier as a biology major with her eyes on medical school.

But a summer spent doing medical research at Tulane exhausted her. It was then that she met with a Teach for America recruiter on campus, curious about how she could help kids. (Another draw: the potential to get aid in paying back school loans through AmeriCorps grants offered to Teach for America teachers.) Her mother, a New Orleans teacher who was fired as part of the mass dismissal after Katrina, had found a new position in a neighboring school district but didn’t want her daughter to enter the profession. Against her mother’s advice, Foster applied, and got a job in her hometown.

* * *

On a warm October morning, Foster’s class mixed rock salt, vanilla, ice, and milk in Ziploc bags, shrieking and laughing as the bubbling liquid exploded all over the place. Speaking in the same New Orleans twang as her students—those bouncy o’s and long, lingering a’s—Foster was teaching her fifth-graders about chemical reactions. But she was also showing them that a black woman, someone just like them, could love and master science.

Foster’s classroom is lined with laminated photos of George Washington Carver, Daniel Hale Williams, and Mae Jemison. At the front of the room, above the whiteboard, is a sign that reads “We Are Science.” Next to it is a poster of Ms. Frizzle, the oddball, red-headed, third-grade science teacher from the beloved Magic School Bus book series. Here, her skin is painted brown.

By her second year at KIPP Central City, Foster was less overwhelmed and had more time to contemplate issues outside her classroom walls. She and other teachers began discussing the lack of diversity on staff.

Foster believes that some white teachers, however well-intentioned, were ill-equipped to handle the vast cultural gaps between themselves and their students. They often missed nuances in language and behavior. They became overly punitive when stressed. She remembers one white teacher screaming at a student for not having the right supplies—hardly a major classroom lapse.

Foster’s concerns mirrored conversations that had been happening at KIPP and across the reform movement. Jarrell says teachers have largely led the school’s push for more racial diversity. Administrators listened, taking into account research supporting the notion that teachers of color can help students of color achieve at higher rates.

The first priority was to hire more local teachers of color. To do that, KIPP Central City Academy has started a partnership with Xavier University of Louisiana, Foster’s alma mater. The school advertises openings through the university’s career center and relies on Xavier counselors for recommendations.

In 2015, KIPP New Orleans, which includes 10 schools across the city, started the Crescent City Teaching Fellows program, a residency program that recruits from local historically black colleges and universities like Dillard University, Southern University at New Orleans, and Xavier. Sixteen fellows make up this year’s inaugural class—57 percent are people of color. The teachers are recent college graduates or career-changers; they work with veteran teachers, attend professional development, and take graduate-level courses. Eventually, they’ll take over classrooms of their own.

At another KIPP school, KIPP Renaissance High School, administrators have been looking for potential teachers among an even younger cohort: their students. This year, principal Joey LaRoche started an Intro to Teaching class in which juniors and seniors learn about education as a career option. In the long run, he hopes the program will help the network grow its own teachers.

But the push to better relate with students hasn’t ended with hiring, as a raft of new but familiar extracurricular activities at KIPP Central City Academy make clear. The school’s pre-Katrina predecessor, Carter G. Woodson Middle School, struggled academically but managed to instill a lasting pride in students and alumni, especially through activities like football and marching band. Such hallmarks were never intended to solve complex issues of crime and poverty. But they could help kids feel like their school was invested in them. Although charter schools in New Orleans have sometimes dispensed with these pastimes, in 2013, Jarrell started a tackle football team, coached by the son of a Woodson alumna. Next came the marching band. And finally, a baton team coached by Kawana Harris, whose two youngest sons attend KIPP Central City Academy.

Last fall, the twirlers spent afternoons in the school’s courtyard under a thick, Louisiana sun, spinning and twirling thin silver batons capped with white pegs on each end. They marched in place to eight counts, and on the rare occasion a student dropped a baton, Harris barked at her to pick it up and get back in formation: What would the squad do if it happened at the school’s first ever homecoming game?

* * *

William Widmer/Slate

Similar teacher diversity efforts are underway at charter schools and school reform organizations across the country.

Teach for America has worked aggressively to diversify its ranks, recruiting at minority-serving institutions (especially through groups like historically black fraternities and sororities). In 2014, the organization announced that nearly 50 percent of its incoming corps identified as people of color, up from 39 percent in 2011.

The Houston-based charter network Yes Prep followed TFA’s example, turning its recruitment focus to Hispanic-serving institutions like the University of Houston, as well as to historically black colleges and universities. Four years ago, the organization lacked a diversity statement. For the 2015–16 school year, half of all new hires were people of color.

“There can sometimes be the sense that it’s harder to recruit teachers of color because there’s all these [academic] barriers,” says Nella García Urban, vice president of talent at Yes Prep. But “we have to have the mindset that the pipeline is there. It’s our responsibility to develop an environment that is attractive to educators of color.” García Urban says the network has also trained recruitment staff in how to avoid hiring bias: consciously or unconsciously seeking out and selecting applicants who are “like me,” which for many charter school administrators means young and white.

Kendra Ferguson, an Oakland, California, native who works as chief people officer for KIPP schools in the Bay Area, says it wasn’t until she created a tangible goal—45 percent of new hires would be people of color—that she began to see real change. In the 2013–14 school year, only 12 percent of new teachers in KIPP Bay Area schools were Latino (55 percent of students across the region’s 11 schools are Latino). The next year, that number jumped to 26 percent. Ferguson credits the improvement to having two Spanish-speaking Latinas on the recruitment team. When potential teachers of color see a diverse recruitment staff and diverse school leaders (six of 11 principals are people of color), they’re more likely to be attracted to the school.

But at KIPP Central City, and throughout the KIPP New Orleans network, teacher diversity efforts haven’t produced such dramatic gains, underscoring the persisting chasm between the school reform movement and veteran educators—particularly veteran educators of color.

Two of the 10 schools in the KIPP New Orleans network, including KIPP McDonogh 15 School for the Creative Arts, employed about half teachers of color last school year. But most of the KIPP schools fell significantly short of that mark. At KIPP Central City Academy, the number of teachers of color rose only slightly between 2012 and 2014, from 11 (38 percent of the teaching staff) to 12 (40 percent), according to state data.

Convincing veteran educators to teach at a school like KIPP Central City isn’t easy, regardless of their race: Charter schools don’t participate in Louisiana’s pension program. They demand grueling work schedules, which make maintaining work-life balance difficult. Foster says her mother probably wouldn’t want to work at a school with no union representation and work schedules that can extend into evenings and weekends.

And then there’s the rising cost of living in New Orleans. Rent has skyrocketed, squeezing out even middle-income families, many of whose members once worked as teachers in the city. “The people who lost their jobs were black. And the people who can’t move back are majority black,” says Luis Mirón, the director of the Institute for Quality and Equity in Education at Loyola University New Orleans.

But even considering these obstacles, charter network leaders could be doing more to tap local—and diverse—talent, says Andre Perry, a former New Orleans charter network leader who now writes and speaks widely on education. “They’re not willing to apply the ‘no excuses’ model in recruiting a workforce in the same way they educate children,” he says. The first recruitment effort begins in the schools themselves, says Perry. And if the pool of local talent isn’t growing, it could be because graduates don’t feel good about their schools. Perry suggests that charter schools focus their efforts on local people and universities, and that they be willing to take chances on people, training and retraining candidates once they’re in the door. “And the fact that we don’t is an indication that we don’t believe local and black folk are worth the investment,” he says. Despite shifts in demographics, nearly 60 percent of New Orleans’ population remains black. “Go after them,” Perry said. “We’re here. We’re not going anywhere.”

Additionally, charter schools too often rely disproportionately on educators of color to staff certain positions in the school, like disciplinarian, according to Perry and others. It raises loaded questions about who is fit to teach and who is fit to punish. Foster says black teachers are often tapped for elective subjects, like music, or coaching extracurricular teams. “That’s powerful, but I think it could be more powerful to see people of color in front of you in your core classrooms,” she says.

Meanwhile, charter school leaders have considerable work to do when it comes to rebuilding trust with veteran educators in New Orleans. Teachers, who made up a major portion of the city’s black middle class, had their livelihoods yanked out from underneath them at their most vulnerable; while their city drowned, they were quietly discarded and replaced.

It wasn’t just the bad optics of a mostly black teacher corps becoming, within just a couple of years, whiter and younger than ever. For some, it was a blunt act of disrespect; outsiders flocked to the city to rebuild that which they did not know, without seeking the wisdom of those who had worked there for decades.

Foster says the recent influx of black teachers at KIPP Central City Academy, however modest, has been positive for her students. But if New Orleans charter schools hope to build sustainable schools with deep roots in the community, they will have to hire more veteran teachers of color—or slowly grow more veterans from their current, mostly young, staffs. That’s not easy to do right now. Foster says she will leave KIPP Central City at the end of this school year. The demanding schedule combined with a full-time master's program left her exhausted after four years. Foster hopes to have her own family soon and struggles to see how she could keep up with both responsibilities. She hopes to stay in education in some capacity, but perhaps not as a classroom teacher.

In the meantime, Foster can take small consolation from one fact: When her kids name their favorite teachers, they’re choosing many different teachers, of many different races. And she’s no longer the only black one they mention.

Tomorrow’s Test is a weeklong series looking at the challenges, tensions, and opportunities as the United States shifts to a majority-minority student population in its public schools—a milestone the country as a whole will reach within the next generation. It is a collaboration with the Teacher Project at Columbia Journalism School, a nonprofit education reporting fellowship.

Read more from Tomorrow’s Test.