The Gay Bar

Can it survive?

So will the gay bar survive, despite the forces circled against it? I've marshaled the best evidence I could unearth in search of an answer.

It's hard to find data on the number of gay bars in America. There's no national organization tracking openings and closings, and word of a new bar or a shuttering rarely carries outside the neighborhood. The best way to find out about gay bars—and gay B&Bs and gay bookstores—is to consult the excellent travel guides put out by Damron (since 1964) and Gayellow Pages (since 1973). Damron currently has 1,405 bars and clubs catering to the LGBT population in its database, while Gayellow Pages lists 1,332.

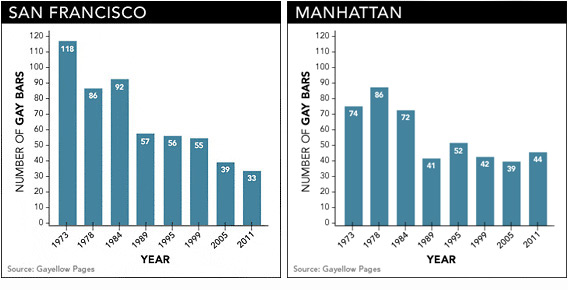

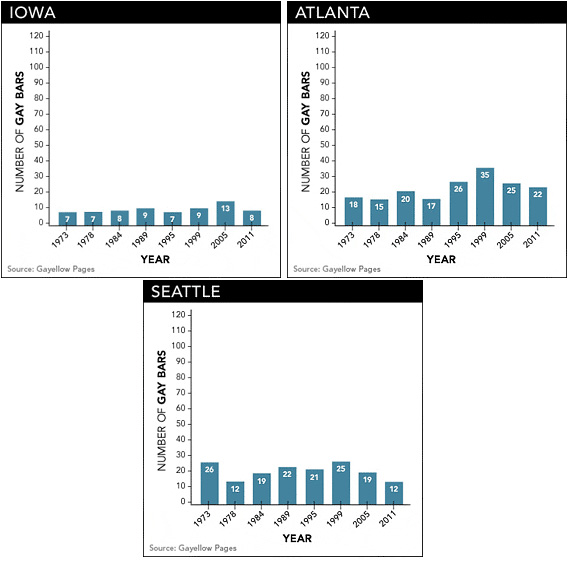

How do those figures compare with numbers from the past? Unfortunately, neither company keeps totals from previous years. (They're publishers, not statisticians.) Damron President Gina Gatta was able to find a database backup from 2005, which showed that the total number of gay bars in the country dropped from 1,605 to 1,405—a 12.5 percent decrease—in the last six years. But without more evidence, it's hard to know whether to attribute that drop to the specific pressures on gay bars or the larger economic pressures of the recession on businesses of all sorts. So I spent some time in the splendor of the New York Public Library Reading Room, paging through old printed copies of the Gayellow Pages. (I chose that source because the NYPL's holdings went back to 1973, and they had enough back issues to allow me to check in every five years or so.)

I focused on Gayellow Pages' listings in four cities—Atlanta, New York (Manhattan only), San Francisco, and Seattle—and in the state of Iowa. I counted bars exclusively for gay men and lesbians, rather than mixed gay-straight venues. The numbers are only as good as the listings; occasionally, I saw a bar coded as gay-friendly that I consider full homo, and I noticed that some bars would toggle between gay and gay-friendly over the years. But I couldn't second-guess the data; perhaps there'd been a change of ownership or clientele, and perhaps—gasp—I was wrong.

Still, as flawed as they may be, the numbers tell a story. In major cities, the number of gay bars has declined from peaks in the 1970s; but they haven't dwindled down to nothing just yet. In 1973, Gayellow Pages placed 118 gay bars in San Francisco; now there are 33. Manhattan's peak came in 1978, with 86; the current tally is 44. The decline in both gay-friendly cities may be attributable to how welcome gays are everywhere; as Gatta, who lives in the Bay Area, put it, "Every bar in San Francisco is a gay bar."

Other areas show more stability. Apart from an odd jump in 2005, Iowa has been home to seven or eight gay bars at a time, more or less, since Gayellow Pages started keeping track. That's apparently what the market can bear. Atlanta has also been steady, after a peak in 1999. Seattle's high-water mark for gay bars was back in 1973, with 26, and after some ups and downs, the latest tally is 12. Seattle is a very gay city, but it's also very integrated, packed with gay-friendly bars like Tommy Gun and Bottleneck.

My limited data set shows a trend, but not a dire one. And it's also important to factor in a larger society-wide shift away from going out. By some accounts we're all becoming anti-social recluses. In 2000's Bowling Alone, Robert D. Putnam assembled an Everest of evidence to show that Americans of all stripes are doing less informal socializing. He cited three independent series of surveys from the mid-'70s up to the late '90s indicating that "the frequency with which Americans, both married and single, went out to bars, nightclubs, discos, taverns, and the like declined by about 40-50 percent over the last decade or two. Whether we live alone or not, Americans are staying home in the evening." Then again, Putnam's research predated the smartphone revolution and he pretty much ignored the Internet. According to a January 2011 survey by the Pew Center's Internet & American Life Project, 75 percent of Americans are active in some kind of group, and Internet users are more likely to be active in voluntary groups and organizations (80 percent) than non-Internet users (56 percent).

These days, being alone doesn't necessarily keep us from interacting informally with others. If I spend an evening watching television, I often get into a series of Twitter exchanges with other viewers, many of whom I've never met in the flesh, and I can comment on my friends' Facebook postings when my attention wanders from the TV screen. Our need for community can be met by interaction with feeds and comment streams, and our desire for niche information can be satisfied by RSS readers and email newsletters. If I can do all this in the comfort of my own home while drinking at liquor-store prices and munching on my favorite foods (instead of pretzels, the satanic snack served by every saloon in America—including gay bars), why on earth would I go to a bar?

The answer, of course, is to have fun. As I was doing the research for this series, I visited a few bars on my own. The experience was dispiriting. It takes an unusual degree of social confidence to take a solo strut into a bar, much less to enjoy the experience. In New York, at least, unaccompanied drinkers seem to be left alone, or at least I was. (I'm aware that the ideal gay bar customer is young and cute, descriptors that don't apply to me.) When I persuaded a friend to come along, we usually wished we were somewhere more suited to catching up.

And then, when I was visiting Seattle, I got together with some dear friends for three nights of scene-scoping, and it was glorious. Each night had a different vibe: a bibulous evening of bar-hopping with a group of pals—gay and straight—with whom I'd shared scores of memorable nights on the town; a quiet night in the city's dyke bar with the woman who had been my most reliable drinking buddy for two decades; and a Sunday smorgasbord of tea dances and Mexican buffet with a merry trio of my oldest friend, a sweet guy I've gotten to know in the last few years, and a woman I met for the first time that evening. I wouldn't want to spend every weekend that way, but it was a fabulous whirl of connecting, kidding, drinking, and having fun. Even crabby old hermits like me crave a night of dancing and fellowship every now and again.

When I asked the bar owners and experts I spoke with if they thought gay bars would survive Entrepreneur magazine's death sentence, all but one said yes—and even the naysayer thought they'd persist in small markets, even if urban gays shifted their patronage to straight or mixed establishments. The alcohol industry will never stop creating environments where customers can purchase its products, and young 'uns will always need a place to come out and learn to dance, even if bars are no longer the meat markets they once were.

Even as we socialize in ways that threaten the survival of the gay bar as an institution, many of us still crave its reliable presence on the scene. It's great to have the variety that parties and special events provide, but we still want the good old gay bar to be there night after night. It shouldn't be necessary to consult a calendar and a street map before going out for a drink with your people. Friends who stopped going to bars years ago expressed a lingering affection for the place that had played an important role earlier in their gay lives, one that could still serve as a refuge when needed. One friend told me, "You don't have to be in constant mortal danger to need a safe haven once in a while. … I occasionally feel the need to be surrounded by people whose basic assumptions on a few key issues are the same as mine." Urvashi Vaid said bars are valuable because they provide a space where gay people "are able to be flamboyant and queer and wacky and silly and not be judged for those expressions."

I thought of those words when I spent a Friday night at Club Basix, a gay bar in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, where 30 or 40 people had gathered to watch a flamboyance of drag queens lip-sync their way through Tina Turner's back catalog. Butch lesbians, middle-aged men in hockey jerseys, apparently straight couples, and cute young guys lined up—literally—to hand dollar bills to the performers on stage. (Since Basix was once a McDonald's, a former life that has not been very well disguised, the term stage is somewhat notional.) Anyone wanting to reward the show girls for their efforts had to approach the performers as they strutted down the "catwalk" (which almost certainly once served as the division between the smoking and nonsmoking sections), hand over the money (this was not a G-string-stuffing kind of place), and accept the queens' thanks, often accompanied by a chaste kiss on the cheek. The exchange was very public and extremely sincere.

Almost everyone in the building tipped the performers at some point during the hourlong show. Maybe the crowd's generosity was a display of working-class solidarity or a kind of camaraderie of the scorned, but it seemed like an expression of gratitude to the queens for bringing people together. There was a sense of family at Club Basix. Many restaurants and bars in Iowa display photos of visiting presidential aspirants, but the glass case at Basix contains funeral programs and newspaper obits of members of the local queer community. Snapshots showed the deceased with their cats and dogs, in shorts, in drag, and in at least one photograph, in a wedding tux. Sure, Club Basix is a bit of a dump, but it's a friendly place for threesomes, drag queens, twentysomethings looking for cheap drinks, and for gays, straights, bis, and those still figuring things out to spend an evening together.

I don't know what impelled that group of Iowans to get into their cars and drive to a club across the freeway from a used-car lot on a Friday night in April, but as long as enough people keep feeling the need for queer communion, America's gay bars will endure. There may be fewer of them, and we may see more folks we think of as "straight" in the crowd, but I believe gay people will always gather to drink and dance under their rainbow flags.