Leading the Witness

Contaminated memories and criminal injustice.

In 1968, Elizabeth Loftus discovered what she wanted to do with her life. She wanted to experiment on people.

Loftus was 24. For several years, she had studied psychology and helped her professors with their research. She had been a cog in the academic system. But now, in her third year of graduate school at Stanford, she was finally getting a chance to design, run, and analyze her own experiments. She knew the thrill of training a rat to press a lever. But this was different. Now she was working with human beings.

Her topic was semantic memory. She was trying to find out how people's brains stored and retrieved words. She couldn't see inside their heads, but she could administer inputs and measure outputs, as she had done with her rat. The inputs were questions, and the output was response time. Sometimes she asked her subjects to name a "yellow fruit." Sometimes she asked them to name a "fruit that is yellow." On average, they answered the latter question a quarter of a second faster than the former. From this, she drew an inference: The brain organized such information by the noun, not the adjective.

Loftus loved the whole thing: conceiving the experiment, trying it out on people, measuring their performance, drawing conclusions about the mind. But not everyone was impressed. Shortly after earning her Ph.D., she had lunch in New York with her cousin, a lawyer. When her cousin asked about her work, Loftus proudly told her about the yellow-fruit study. Her cousin dryly asked how much it had cost the government.

The conversation stung Loftus. She was running her own memory experiments, but they were just about words. Why did it matter how people recalled yellow fruit? Wasn't there something more worthwhile to study?

What did she really care about? As an experimental psychologist, she decided to answer the question by studying her own behavior. What did she talk about when the topic was hers to choose? What did she like to bring up at parties? The answer was crime. She loved books, movies, TV shows, and news stories about it. Maybe she could become a crime expert. She could use the science of memory to help the justice system.

The first step was to find a project somebody would pay for. The Department of Transportation was offering money to study car accidents. Accidents weren't crimes, but they involved eyewitnesses, so she started there. She showed people films of collisions and quizzed them about what they had seen. Sometimes she asked how fast the cars had been going when they "hit" or "contacted" each other. Sometimes she asked how fast they had been going when they "smashed" into each other. The "smashed" question produced estimates 7 miles per hour faster than the "hit" question and 9 miles per hour faster than the "contacted" question. The questions were skewing the answers.

In another experiment, she showed her subjects a multi-car collision and asked some of them, "Did you see a broken headlight?" She asked others a leading version of the question: "Did you see the broken headlight?" Of the six questions posed in this dual format, three referred to things that weren't in the film. Compared with subjects who heard the question with an "a," those who heard it with a "the" were twice as likely to say they had seen a bogus item. (To experience one of Loftus' traffic experiments, click on the adjacent

Still, that was just lab work. Loftus wanted to get involved in a real court case. In 1973, after moving to the University of Washington, she called up the Seattle public defender's office and volunteered to help as a memory expert. In exchange, she got to watch the case unfold. It was a murder trial that hinged on conflicting memories over how much time had elapsed for premeditation. It ended in acquittal.

Loftus packaged her memory expertise with her accident studies in an article for Psychology Today. She challenged the reliability of eyewitness testimony, mentioned her work in the Seattle murder case, and noted that the defendant had been acquitted. It was practically an advertisement. Attorneys read the article and picked up their phones. Her career in legal consulting was launched.

She was exactly what defense lawyers needed. The chief threat to their clients was incriminating witness testimony. Loftus could shake the jury's faith in such recollections without attacking the witness personally. Memory errors were natural. The witness, like the defendant, was innocent. Even police, who caused misidentifications by contaminating witnesses' memories with mug shots and lineups, often didn't realize what they were doing.

Over the next 35 years, Loftus testified as a memory expert in more than 250 hearings and trials. She worked dozens of famous cases: Ted Bundy, O.J. Simpson, Rodney King, Oliver North, Martha Stewart, Lewis Libby, Michael Jackson, the Menendez brothers, the Oklahoma City bombing, and many more.

Why did a woman who had endured assault in her own life defend accused predators? Part of it was the structure of criminal law: Her work created doubt, and doubt was an ally of the defense. Part of it was her empathy for the accused: She had always been suspicious of criminal allegations and lenient toward small-time offenders. And where empathy failed, scientific rigor took over. Memory's fallibility was a fact. By testifying to that fact, she believed she was serving justice.

Loftus alters Lesley Stahl's eyewitness memory

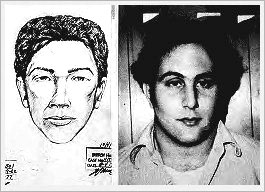

Her job was to explain how memory errors could contaminate eyewitness testimony. For example, when eyewitnesses were shown lineups of possible culprits, they sometimes selected a face that was familiar for a different reason. Loftus demonstrated this by showing experimental subjects six photos while they listened to a crime story. One photo depicted the culprit; the others depicted innocent characters in the story. Three days later, she showed the same subjects a photo of one of the innocent characters along with three photos of other people. From these four pictures, she asked them to pick the criminal. Twenty-four percent of the subjects correctly refused to pick a photo. Sixteen percent picked one of the three new photos. Sixty percent picked the photo of the innocent character. They remembered it from the crime story but confused it with the perpetrator.

Police lineups worsened this confusion. In another experiment, after watching a mock crime, subjects were offered a lineup that didn't include the perpetrator. One-third of them picked somebody anyway. But when the cops conveyed extra confidence—"We have the culprit and he's in the lineup"—78 percent of the subjects picked somebody.

Then there were prosecutions based on coached child testimony, such as the McMartin Preschool sex-abuse case. To measure children's suggestibility, Loftus and a colleague showed them several one-minute films, followed by leading questions. "Did you see a boat?" they asked one child. Afterward, the child remembered "some boats in the water." "Did you see some candles start the fire?" they asked another. "The candle made the fire," the child said later. Other kids, after being asked about bees and bears, recalled bees and bears. None of these things—bees, bears, boats, candles—were in the films.

Not even Loftus was immune to suggestion. In 1988, after 13 years of testifying about memory's fallibility, she was told by her uncle that she was the one who had found her dead mother in the swimming pool. The sights and sounds of that awful morning came back to her—the corpse face down, the nightgown, the screaming, the stretcher, the police cars. But within three days, her uncle recanted the story, and other relatives confirmed that her aunt, not Loftus, had found the body. The memories of the memory expert were false.

The incident strengthened Loftus' conviction that such recollections shouldn't be trusted in court. The more cases she saw, the more passionate she became about her work. She saw herself as Oskar Schindler, rescuing as many innocent souls as she could. "The beauty I find in helping the falsely accused is something I like about myself," she wrote in an essay years later. "It's the deeper part of who I am."

The passion and the work took their toll. In court, she endured cross-examination and vilification. And at home, her husband gave up competing for her attention. In 1991, they divorced.

But by then, she had a bigger problem.

Next: The Recipe.

Like Slate on Facebook. Follow us on Twitter. William Saletan's latest short takes on the news, via Twitter: