Where's Pepper?

In the summer of 1965, a female Dalmatian was stolen from a farm in Pennsylvania. Her story changed America.

First, Ivan Pavlov would sever a dog's esophagus and sew the loose ends to its throat, leaving a pair of adjacent holes that connected, by separate passages, to its mouth and stomach. Then he'd slice through the dog's abdomen, carve a hole in the wall of its stomach, and stitch open another permanent wound.

The dog, left hungry from the night before, would be harnessed to a wooden stand and presented with a bowl of raw meat. No matter how much it ate, it never got full—the dog chewed and swallowed, but the masticated meat would erupt from its esophageal opening and dribble back into the bowl, whereupon the dog would lap it up all over again. In the meantime, a glass tube attached to the animal's stomach opening allowed its gastric secretions to drip into a collecting bottle, so they could be filtered, analyzed, and sold to the public as a remedy for dyspepsia.

As historian Daniel P. Todes writes in Pavlov's Physiology Factory, these thrice-perforated animals enabled a new approach to science—the chronic experiment—and a series of discoveries about the nervous control of digestion for which Pavlov won the Nobel Prize in 1904. (At the time of the award, he was just beginning to study how animals learned to salivate at the sound of a buzzer.) * In 1935, just before his death, Pavlov approved the design for a monument to his canine test subjects, erected on the grounds of the Institute of Experimental Medicine in St. Petersburg, Russia. A bronze plaque on one side depicts the dogs on laboratory tables, tied to their wooden frames with their fistulas open. "We must painfully acknowledge that, precisely because of its great intellectual development, the best of man's domesticated animals—the dog—most often becomes the victim of physiological experiments," he had written in 1893. "The dog is irreplaceable; moreover it is extremely touching. It is almost a participant in the experiments conducted upon it, greatly facilitating the success of the research by its understanding and compliance."

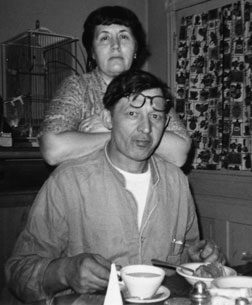

No one can say exactly how old Pepper was in the summer of 1965, but every member of the Lakavage family remembers her gentle disposition. There were plenty of other dogs racing around their farm at the bottom of Blue Mountain, but the Dalmatian named Pepper—trim and affectionate, pelted with splotches of black—was always Mom's favorite.

Julia Lakavage preferred to take in strays, but she made an exception when she saw Pepper at the decrepit Spatterdash kennel a few miles down the road. Julia and her husband, Peter, lived on 82 acres in the hills above Slatington, Pa., two hours due west of New York City. Peter had a job with Bethlehem Steel; Julia had polished shells there during the World War II, but by the 1960s she was working the night shift as a nurse for the Good Shepherd Home in Allentown. They had four daughters—Star, Carol, Kathy, and Peggy—and a 7-year-old grandson named Michael.

Pepper loved a car ride, and some nights Julia would take her along to the hospital in Allentown. If Julia were the only nurse assigned to the floor, she'd bring the dog on her rounds of nursing home residents and handicapped orphans. The patients loved it, remembers Star. They would call for Pepper as soon as they heard her paws click-clacking along the linoleum hallway. One day, Julia promised, she'd buy "Nurse Pepper" a little white hat.

But Pepper didn't come to work with Julia on the night of Tuesday, June 22, 1965. Sometime that evening, the Lakavage children let Pepper out onto the back porch for her usual evening stroll. When they opened the door half an hour later, the dog wasn't there. "Pepper always came, no matter what," says Michael. "You'd go to let her back in, and she'd be laying on the porch, waiting." For the first time that any of them could remember, Pepper was nowhere to be seen. Michael remembers standing in front of the house, calling into the darkness.

By the next morning, the Lakavages knew for sure that Pepper was gone.

Over the next few days, Julia mobilized her family in a desperate search for the missing dog. According to a short version of the incident that was published five months later, improbably, in the pages of Sports Illustrated, "all during the following week, a heartbroken Mrs. Lakavage advertised and hunted for her dog." Indeed, no one in the family had ever seen Julia so upset. ("Dogs are like family members," she would later tell a newspaper reporter, "children that don't grow up.") The Lakavages fanned out through the woods and along the dirt road that ran past the farm. They checked with the neighbors up the hill and drove to the top of Blue Mountain to call for Pepper from the ridge under the power lines. Julia posted signs and telephoned everyone she knew.

Michael assumed that a neighbor had run over Pepper with a car—there was kid up the road who messed around with muscle cars—but Julia talked to someone who had seen a man loading a Dalmatian into the back of a truck near their farm.

For years, animal welfare groups had been warning of nighttime forays by pet snatchers in unmarked vans. Stolen dogs, they said, were being sold to laboratories and subjected to painful experiments. In 1961, Walt Disney had released 101 Dalmatians—a hugely successful film about pet theft—and the Humane Society of the United States had begun to look into a network of illegal animal dealers operating across Pennsylvania and Maryland. Navy veteran Frank McMahon led the investigation and hired Dec Hogan, a rough-and-tumble nightclub owner, to pose as a dealer in the field. Along with another investigator, Dale Hylton, they began to stake out the rural auctions where stray animals were traded before being shipped off to research laboratories in big cities. The team devoted much of its energy to a notorious Amish market down in Lancaster County, known as the Green Dragon.

Named after a Chinese restaurant on the Atlantic City, N.J., boardwalk, the Dragon had been operating in the town of Ephrata since 1932. (It's still open.) Fridays were auction days, with sales of livestock running all afternoon. The small-animal sale started by 7 p.m.: An auctioneer would set up in the middle of a rectangular pen, about 20 feet by 40 feet, surrounded by bleachers. Crated dogs and cats were rolled inside one by one and put up for bidding.

Hogan remembers thousands of people at the market, Amish vendors selling pies and cookies, and the animal dealers—"grass-roots kinds of guys, doing it for a six-pack of beer"—carting in stray dogs for sale. The winter before Pepper disappeared, investigators had watched one dealer purchase hundreds of dogs at the Green Dragon and pack them into his truck in chicken crates. When he returned home the next morning, the police were waiting; he was arrested for cruel treatment of 7,000 animals on his farm and paid a $67 fine.

Likely at the suggestion of her local SPCA, Julia Lakavage decided to investigate the Green Dragon market for herself. On Friday, June 25, three days after Pepper vanished, Julia put her daughter Star and grandson Michael into the backseat of a finned, brown '60 Ford Fairlane with a green interior and drove an hour or so down to Ephrata.

Star, who was 14 at the time, remembers rows of wire crates at the Green Dragon auction. They were stacked two and three on top of one another, filled with dogs and goats, and left out in open areas without shade. The Lakavages visited at least one more auction in the days that followed. But Pepper was nowhere to be found.

Almost 200 miles away, in the Pennsylvania mountains near the Maryland border, a 77-year-old outdoorsman named Jack Clark was getting ready for his weekly animal swap. Jack was burly and gregarious, with a generous gut and a bald head. He lived out in the woods of Black Valley and kept by his house an extensive menagerie of woodland and other critters. There were pet raccoons and caged skunks, penned-up groundhogs and captured foxes. But above all, there were dogs.

Jack made his living as a dogcatcher, and he kept hundreds of his quarry boxed up by the creek out back. His grandkids remember seeing big dogs and little dogs on the property, mutts and purebreds, golden retrievers and Dalmatians. "I remember laying upstairs in bed at nighttime," recalls his grandson Terry, "and falling asleep to the sounds of the dogs barking."

Everyone in town knew Jack and his big, green pickup truck, with the wood-framed animal cab loaded on the back. When he was in the area, he'd stop in at Sponsler's Superette every few days to pick up meat scraps for the animals. Jack would come and go, disappearing one day and returning later in the week with 10 or 15 dogs in tow.

There was talk among the locals that Jack wasn't just picking up strays, that he'd steal dogs out of people's backyards and sell them off to medical labs in Philadelphia. But the county dog law enforcement officer—Fred Sponsler, who owned the Superette where Jack did his shopping—appears not to have filed any charges. Later on, Terry Clark and his sister Kay would conclude that their granddad had been carting live cargo to research labs in Harrisburg.

Jack's friends and fellow dealers would converge on his property every weekend to trade horses, goats, cats, and dogs while their children played on the ponies out back. It's impossible to know whether Jack Clark made a dogcatching expedition up to Slatington in June of 1965, but, one way or another, Pepper seems to have ended up at his weekly swap in Black Valley, on Sunday, June 27, five days after she disappeared.

By Tuesday, June 29, one week after her disappearance, Pepper was in the hands of Jack's good friend Bill Miller.

If you lived in Slatington, or Allentown, or just about anywhere in the region, the summer of 1965 would have been long and miserable. A four-year drought, made worse by a run of scorching, cloudless days, pushed New York City's reservoirs to half-capacity. Golf courses dried up, the rhododendrons and azaleas crumpled at the city's botanical gardens, trains and buses went unwashed, and the mayor proposed tapping the Hudson River for drinking water.

In all that nasty summer, no single day was more vile than June 29. The temperature reached 95 degrees in the afternoon, the humidity 50 percent. The New YorkTimes pronounced that an "asphalt-softening, brain-fogging heat" had overtaken the city. And somewhere on the 170-mile stretch of Route 78 that runs from Harrisburg, Pa., to the New York state border, 18 dogs—including two boxers, a Weimaraner, several mixed collies, and a pair of female Dalmatians, one of them Pepper—were locked in a small enclosure on the back of Bill Miller's pickup truck, crammed inside with a pair of goats.

Bill Miller ran Broken Arrow Kennels out of McConnellsburg, a half-hour's drive east from Jack Clark's place in Black Valley. Like the other dealers in Clark's circle, Bill was an older guy—and a regular target for Humane Society investigators. In February 1964, Dale Hylton had visited his farm in the guise of a buyer for a Long Island hospital, successfully placing an order for 170 research dogs. The unsanitary conditions he found there were grounds for a search warrant, and he later returned with a constable to file charges of cruelty to animals.

Miller would have another run-in with the authorities at the end of June 1965. He seems to have set off from McConnellsburg on Tuesday afternoon, a week after Pepper disappeared from the Lakavage farm, and made his way across the Susquehanna River on Interstate 81. From there he would have had a straight shot through Allentown and into New Jersey. But a few hours later, with Miller just moments away from crossing the New Jersey border, the local police in Easton pulled his truck off the road and asked to look in the back.

Distressed by the sight of 20 animals huddled in a cab with little ventilation, the cops wrote out a pair of tickets—$74 for overloading the vehicle and $10 more for "cruelty in transport"—and handed over the dogs and goats to the county animal shelter. Miller said he was on the way to Arthur Nersesian's research holding facility in High Falls, N.Y., and that he'd be back the next day to pick up his haul with a bigger truck. The shelter's proprietors agreed to release the animals if and when Miller could deliver the proper bills of sale. They photographed the dogs that night.

Miller returned to Easton Wednesday morning, as promised, with money to pay his fines and a larger vehicle. The shelter turned him away—the new truck had no air vents in the back, and he hadn't yet provided any documentation for the animals.

At 9:15 that evening, Miller showed up at the shelter once more—in a third, still-larger truck, a bundle of receipts in hand. The staff at the shelter went over the sales slips and, having stalled as long as they could, reluctantly turned over the cargo. Months later, Frank McMahon of the Humane Society would tell Congress that the receipts may have been forged.

The next day, the Allentown Morning Call ran a story about the episode, under the headline "18 Dogs, 2 Goats Seized; Ownership Proof Sought." By that point, though, Pepper was back on the road.

Peter Lakavage knew his wife was frantic, but there was only so much he could do from a hospital bed in Allentown. Sometime in late June, Peter had suffered a heart attack, one of several he would have over the next few years. (The final, fatal blow came in 1969.) On the morning of Friday, July 2, Peter flipped open a copy of the Morning Call in his hospital room and saw an article following up on the previous day's story: "20 Animals Resume Their Trip." Among the dogs listed in the article were two purebred, female Dalmatians. Peter climbed out of bed and called his wife.

Julia dialed the Easton shelter as soon as she got the news. One of the impounded Dalmatians had been 8 months old, the shelter's proprietor told her, and the other was an adult. Julia could try to identify Pepper from the photographs taken Tuesday night, but those weren't due back from the developer until later in the afternoon. Meanwhile, the county SPCA had already gotten in touch with animal activists in Washington, D.C., and in upstate New York, where Miller said he was taking the dogs.

Within the hour, Julia had her grandson Michael and daughter Star in the back seat of the Ford Fairlane and Carol in the front, and they set off on the 130-mile drive to High Falls, N.Y. Star remembers stopping at pay phones along the way so her mom could arrange meetings in New York and make sure there was someone to cover her nursing shift at Good Shepherd.

The family arrived that afternoon at an upper-middle-class neighborhood in Ulster County. Star remembers the well-appointed houses and manicured gardens: "Here we were, this little family from god-awful nowhere on some farm," she says, "and these people from really nice homes were talking to my mom. … I thought, 'Holy cow, we're just looking for our dog—we just want to know what happened to our dog.' " Having conferred with members of the local humane groups, Julia drove out in search of the Nersesian farm.

At 2 that afternoon, she arrived with her children at the New York State Police station on the highway near Kerhonkson. Julia described her search for Pepper and asked for help. Would the troopers please come up to the farm on Clove Valley Road?

Arthur Nersesian was 55 years old, an avid boxing fan, and a retired New York City cop. For two decades he'd run down hoodlums out of the 3rd Precinct in Chinatown, but in 1957, he packed up his place in Queens and moved the family to a plot of land upstate, with a Dutch stone house, a couple of grain silos, and a gambrel-roofed barn.

The property was ringed with "No Trespassing" signs, and locals remember an alarm that went off whenever a vehicle entered the driveway. Nersesian had other ways of keeping out strangers. According to the Morning Call, he'd already filed a $2.5 million lawsuit against a New York SPCA unit for allegedly entering the farm without permission.

The state troopers on Route 209 may well have known the Nersesians were selling dogs for research down in the city. (The family is still proud of the farm's contribution to the early heart-transplant studies in Brooklyn.) But there wasn't much the police could do when the Lakavages arrived that afternoon. A trooper informed Julia that a search would be impossible without a warrant, and there was no way to get a warrant without hard evidence that Pepper was on the premises. "She wasn't going to go out there," the trooper said later. "She was kind of upset because she was pretty attached to the dog."

With no way to get onto the Nersesian farm, Julia turned the car around. By Friday night, the family was back home in Slatington. Reporters called the house that night, but Julia was reluctant to discuss the case, fearing that too much publicity would put Pepper's life in danger. "It's just a long-shot chance," she said, finally. "I didn't mean to make trouble, I only wanted a chance to look at the dogs to see if my dog was there."

At the offices of the humane societies and other animal welfare groups in Washington, 47-year-old Fay Brisk was known as the "dog dealers' Madame Defarge." A former member of the Women's Army Corps, Brisk had gotten kicked out of the military for marrying a fellow officer without permission, and took a job as an information specialist with the government. She was still on the federal payroll in the 1960s, detailed to the White House with the Small Business Administration. On weekends, though, Brisk would sometimes travel back to Berks County, Pa., where she grew up. There she would pursue her decadeslong obsession with animal welfare.

Brisk's hometown was just 20 miles from the dog-and-cat auctions of the Green Dragon, and she'd worked as a reporter for the Reading Eagle and the Philadelphia Record. Over the years she cultivated a rich network of sources and friends among the animal traders.

One of those sources tipped off Brisk about Julia Lakavage and the search for Pepper. She may have been following the events from her home in Georgetown, or it's possible she traveled to High Falls, N.Y., to meet Julia in person. In any event, she learned on the afternoon of July 2 that the Lakavages had been denied entry to the Nersesian farm and that the local authorities were reluctant to deliver a search warrant. She decided to take the matter to the Capitol.

Brisk called her friend Christine Stevens, founder and chief lobbyist of the Animal Welfare Institute. Stevens was elegant, cultivated, and as well-connected as anyone in Washington. Her husband, Roger, had worked closely with Presidents Kennedy and Johnson; a few months later, he would be tapped as the founding chairman of the National Endowment for the Arts. The Stevens were also close with a patrician Pennsylvania senator named Joe Clark. At Christine's urging, Clark had introduced a series of unsuccessful laboratory-animal-care bills dating back to 1960.

Sen. Clark had all but shut down his office for the July 4 holiday. Weekend coverage fell to a junior staffer named Sara Ehrman. She answered when the call about Pepper came in late on Friday afternoon. Ehrman would eventually become a major player in the Democratic Party, a board member of the American Israel Public Affairs Committee, and a close friend to the Clintons. But in the summer of 1965 she was a peon in Joe Clark's office. "I don't even like dogs," she says now, with renewed pique. But she passed on the message, and word came back from the senator: "Do what you're supposed to do for Christine."

Ehrman looked up the House representative for Ulster County, N.Y., and found Joseph Resnick—a crusading liberal who had just defeated a 14-year incumbent in an overwhelmingly Republican district. There couldn't have been a man in Congress more different in style from Joe Clark. Resnick was a high-school dropout, a former television repairman who had made tens of millions of dollars by inventing the preassembled, rotating TV antenna. According to the New York Times, the stocky, cigar-smoking business executive rode around in a "telephone-equipped gold-color Continental." His stint in Washington was brief—Resnick died of unspecified causes in a Las Vegas hotel room in 1969—but unusually productive. During four years in office, he worked up a distinguished résumé on civil rights and agricultural reform, and patented new machines for blow-molding and decorating plastic containers.

Resnick was eager to intercede for the Lakavages and their missing dog. He placed a call to Arthur Nersesian that same afternoon and made a personal request that Julia be allowed to check the premises. Not without a search warrant and charges in writing, the ex-cop replied.

Their exchange was described in the next day's Morning Call: "Stolen … Sold? Trail Leads to N.Y.—Love for Dog Stirs Two States."

Resnick was outraged. He contacted the FBI on Friday evening to find out if moving stolen dogs across state lines was a federal crime, and then he pressured the Ulster County district attorney's office for a search warrant. But Nersesian held firm, and no one set foot on his farm to look for Pepper.

There was a fog in Allentown on Monday, July 5, and thunderstorms delivered some much-needed rain. At some point during the holiday weekend, Fay Brisk had called the Pennsylvania state troopers, and soon the dog law enforcement officer down in Everett, Fred Sponsler, was investigating Pepper's whereabouts as well. Bill Miller told the authorities that he'd gotten the Dalmatian bitch from another friend of Jack Clark's named Russ Hutton, who'd bought the dog off Jack Clark. Sponsler said he couldn't find Clark to confirm the story, but he nevertheless concluded that Clark had gotten the dog in question from "an Altoona man who got rid of it for eating chickens."

In any case, Bill Miller revealed one more crucial detail. He'd never actually driven up to Nersesian's farm in High Falls, he admitted to the police. Instead, he'd loaded up his truck at the shelter in Easton on Wednesday night and gone straight into Manhattan. On the previous Thursday, June 30, he sold a dozen dogs and both goats to Einstein, St. Luke's, and Columbia hospitals. And then he drove up to the Bronx and unloaded the rest of the animals—including both Dalmatians—to Montefiore Hospital. He would have been paid about $15 for Pepper and perhaps $300 for the entire truckload of animals.

The troopers gave Fay Brisk the news first, and she telephoned over to Montefiore that night. The switchboard operators told her no one was working in the animal quarters to answer her questions. Years later, Brisk would claim to have heard the jangling of dog tags at the other end of the line when she finally got through the next morning. Yes, someone at the hospital told her, the two Dalmatians did come in the previous week, but no, the older one was no longer there. On Friday, while Julia Lakavage was talking to the state troopers in Ulster County, her dog Pepper was splayed out on an operating table in a large building on Gun Hill Road in the Bronx. Medical researchers had tried to implant her with an experimental cardiac pacemaker, but the procedure went awry, and she died. The dog's body had already been cremated.

A hospital spokesman explained later that the order had gone out for six male Dalmatians, to be paid for by weight. The dealer had brought in two females instead.

Pepper's journey in the summer of 1965 helped start a national media sensation and a broad panic over the theft of pets for biomedical research. Her death on an operating table in the Bronx would help animal welfare advocates break a long-standing stalemate in Congress and push through the most significant animal-protection bill in American history. At the same time, she became a martyr to the cardiology revolution at a crucial moment in its development. Pepper also represents a turning point in science, from an earlier age when animals for experiment would be plucked from the road or the river, to a new era of standardized, mass-produced organisms that can be shipped right to the laboratory door. In a five-part seriesto be published over the course of this week, Slate will explore her legacy.

Correction, June 9, 2009: This article originally referred to Pavlov's discovery that "animals would drool at the sound of a bell." That's a widely held misconception about his work. It was already well-known that animals could learn to salivate in response to sounds; Pavlov helped elucidate the meaning and function of these conditioned reflexes. References to a "bell" in his work are the result of a long-standing mistranslation from the Russian of the word for "electrical buzzer." In fact, Pavlov only used a bell once or twice in more than 30 years of research. (Return to the corrected sentence.)