Ice Flows

-

CREDIT: Photograph courtesy the Extreme Ice Survey.

CREDIT: Photograph courtesy the Extreme Ice Survey.Glaciers move at, well, a glacial pace. But in recent decades, ice has been disappearing from the Arctic and mountain ranges at a shocking rate. Ice that formed over centuries is now melting in a matter of years or months, contributing to rising sea levels and profoundly altering hydrologic cycles and water supplies to regions that rely on glaciers for their water source. Still, the movement is so gradual that its scale is invisible to the casual observer. So how do you communicate the rapid melting of glaciers to nonscientists? Forget graphs, charts, and ice core measurements. Bring in time-lapse photography, a technique to compress a massive number of sequential photographs, taken at set intervals, into what looks like a sped-up video. James Balog, pictured to the right, is the founder and director of the Extreme Ice Survey, a spectacular set of time-lapse images chronicling glacial movement—the largest project of its kind. Here, Balog stands near Alaska's Columbia Glacier, which moves at 50 feet per day, or eight times faster than it did 30 years ago.

-

Photograph courtesy the Extreme Ice Survey.

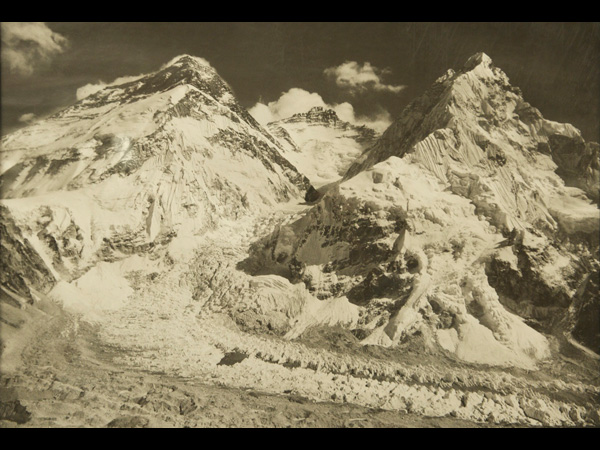

Photograph courtesy the Extreme Ice Survey.Last May, the Extreme Ice Survey installed five custom time-lapse cameras in the area around Mt. Everest to record the flow of glaciers. The Khumbu Icefall, pictured at right, is at the end of the Khumbu Glacier and just above the Everest Base Camp. The icefall advances three to four feet down the mountain every day, moving blocks of ice the size of cars and refrigerators. Mountaineers typically leave base camp in the middle of the night to avoid climbing on the Khumbu Icefall while it's moving fastest.

Everest, the Earth's highest peak, is sometimes called the water tower of the world, because as many as 2 billion people rely on its glaciers as a source of water, Balog explains. Aside from their visual appeal, time-lapse photographs also help scientists to map changes in the position and surface of the ice, which in turn helps them to determine how much snow accumulates during the year and how fast the glaciers are melting.

-

Photograph courtesy the American Alpine Club and the Extreme Ice Survey.

Photograph courtesy the American Alpine Club and the Extreme Ice Survey.Balog chose the camera locations based on this photo taken by Swiss mountain climber Norman Dyhrenfurth in 1963, as well as photos taken by a British reconnaissance team in 1951. He found the images in the American Alpine Club's archives. Balog then used the club's 6-foot-tall scale model of the Everest massif to determine where to position the cameras.

-

Photograph courtesy the Extreme Ice Survey.

Photograph courtesy the Extreme Ice Survey.Balog's team poses with the cameras they installed across from the Khumbu Icefall. Extreme Ice Survey has 31 active cameras aimed at 18 glaciers around the world, including Alaska, the Rocky Mountains, the Alps, Greenland, and Nepal. Balog spent months experimenting and tinkering before he settled on the cameras EIS uses today. Each is about the size of a large shoebox and weighs 70 pounds. They're made with Nikon digital D-200 SLR cameras powered by batteries and solar panels. Each camera takes more than 5,000 images per year—one every 30 minutes during daylight. The cameras on Everest together generated 28,000 images during their nine-month stint, Balog says. Each camera is designed to withstand extreme conditions, including falling rocks, temperatures that dip to 40 degrees Fahrenheit below zero, onslaughts of snow and rain, and 160-mile-per-hour winds. Still, some have been demolished by rock falls and others have been lost to rapid glacial retreat.

-

Photograph courtesy the Extreme Ice Survey.

Photograph courtesy the Extreme Ice Survey.Balog is a keen student of nature. He began as an adventurer and mountain guide, then became a scientist—earning a graduate degree in geomorphology, the study of landforms on the surface of the Earth—and then a photographer. "I want to see things with a capital S, engage with nature and understand the soul and heartbeat of things," he said.

-

Photograph courtesy the Extreme Ice Survey.

Photograph courtesy the Extreme Ice Survey.Balog cooked up the idea for cameras on Everest when he met Conrad Anker, an American rock climber and mountaineer best known for discovering, in 1999, the body of George Mallory, the famed British mountaineer who took part in the first expeditions to Everest in the early 1920s and lost his life on the mountain in 1924. Anker led the EIS expedition team through the challenging terrain to install the cameras on May 8, 2010, and to retrieve the images in February.

-

Photograph courtesy the Extreme Ice Survey.

Photograph courtesy the Extreme Ice Survey.Everest, though scenic, is a difficult place to photograph. "In the spring season comes the pre-monsoons, which brings clear skies in the morning, but sun is behind the mountain. The sun comes up high, raking down through the icefall. Then, in the western sky, clouds build up and you can't see anything. When the sky is not obscured by clouds, you get fantastic light," Balog said.