Sad Face

Another classic finding in psychology—that you can smile your way to happiness—just blew up. Is it time to panic yet?

Lisa Larson-Walker

In the spring of 2013, a 63-year-old social psychologist in Wurzburg, Germany, made a bold suggestion in a private email chain. For months, several dozen of his colleagues had been squabbling over how to double-check the scientific literature on “social priming,” the idea that even very subtle cues—the height of a chair, the temperature of a cup of coffee, the color of a printed word—can influence someone’s behavior or judgment.

Now the skeptics in the group wanted volunteers: Who among the priming experts and believers would help them with a large-scale replication effort, in which a major finding would be tested in many different labs at once? Who—if anyone—would agree to put his research to this daunting test?

The experts were reluctant to step forward. In recent months their field had fallen into scandal and uncertainty: An influential scholar had been outed as a fraud; certain bedrock studies—even so-called “instant classics”—had seemed to shrivel under scrutiny. But the rigidity of the replication process felt a bit like bullying. After all, their work on social priming was delicate by definition: It relied on lab manipulations that had been precisely calibrated to elicit tiny changes in behavior. Even slight adjustments to their setups, or small mistakes made by those with less experience, could set the data all askew. So let’s say another lab—or several other labs—tried and failed to copy their experiments. What would that really prove? Would it lead anyone to change their minds about the science?

The group had hit an impasse. According to an account of the email thread in Nature, the Nobel Prize–winning psychologist Daniel Kahneman tried to goad the priming experts into playing ball. Their unwillingness to engage, he wrote the group that February, “invites the interpretation that the believers are afraid of the outcome.”

Then on March 21, Fritz Strack, the psychologist in Wurzburg, sent a message to the guys. “Don’t get me wrong,” he wrote, “but I am not a particularly religious person and I am always disturbed if people are divided into ‘believers’ and ‘nonbelievers.’ ” In science, he added, “the quality of arguments and their empirical examination should be the basis of discourse.” So if the skeptics wanted something to examine—a test case to stand in for all of social-psych research—then let them try his work.

Let them look into the most famous study on his résumé, literally a textbook finding in the field. Let them test the one in which he demonstrated that when a person shapes his mouth into a smile or a frown, even inadvertently, it changes how he feels. In 1988, Strack had shown that movements of the face lead to movements of the mind. He’d proved that emotion doesn’t only go from the inside out, as Malcolm Gladwell once described it, but from the outside in.

Let them replicate that result.

* * *

A few weeks ago in Rio de Janeiro, the Olympic swimmer Michael Phelps was caught on camera as he readied for a race. He had headphones on beneath his warmup parka, and his face was drawn into a cartoon scowl—eyebrows tilted inward, lips curled toward the floor. As #PhelpsFace spread across the internet, so did efforts to explain it. Was Phelps focused on engaging task-relevant neural networks as a means of “getting in the zone”?

Or maybe he was using “facial feedback,” and he meant to have that angry look. The flexion of his facial muscles would have led to activation in his amygdala, one neuroscientist explained to Outside magazine, and helped prepare his body for the coming action. This concept has been a standard in self-help for many years: Fake it till you make it; sulk until you hulk. Act the way you want to feel, and the rest will fall into place. A frown can rev you up. Smiling can make you happy or decrease your stress.

Most accounts of the face’s untapped power trace the notion all the way back to Charles Darwin, who proposed in 1872 that displaying outward signs of an emotion can intensify its feeling. “He who gives way to violent gestures will increase his rage,” Darwin wrote in The Expression of Emotions in Man and Animals. He footnotes this idea to Louis Pierre Gratiolet, a French brain anatomist whose version of the theory, published several years before, had gone a little further: “Even incidental movements and positions of the body will result in associated feelings,” Gratiolet declared in 1865. By his interpretation, gestures and expressions needn’t just embellish on emotions; they could help create them, too.

By the 1880s, William James had pushed this notion of emotion to its limit: For all intents and purposes, he said, expressions were emotions. When a person becomes angry, the movements in her body lead the way. If her anger never made its presence known—if her face did not flush, her nostrils did not flare, her teeth did not clench, or her breathing did not hurry—then it would be as if she’d never been enraged at all. Emotions simply don’t exist unless they’re manifest. Phelps without his #PhelpsFace isn’t feeling anything.

Starting in the 1960s, psychologists tried a different explanation. Maybe our emotions are constructed ex post facto, they proposed, as a way for us to explain our own behavior. If I notice that I’m sweating and my skin is hot, I’ll look at all the other cues in my environment—where I am, what I’m doing, who happens to be standing right in front of me—and then my mind will use that information to determine what I’m feeling. In the same way that I try to guess the mental states of others (he’s trembling on stage; he must be scared of public speaking), I can do my best to guess my own.

Theories of facial feedback have since splintered into subtle variations. Some researchers argued, as Darwin had, that a person’s faces turned her pre-existing feelings up or down, like adjusting volume on a stereo. Others thought expressions might affect emotions’ quality—their tone or timbre, even their description.

In lab experiments, facial feedback seemed to have a real effect. But it wasn’t clear exactly how the feedback system worked. Were people simply guessing what their faces meant, through some conscious or unconscious action of their minds? Or might smiles work directly on the brain to bring about emotions, without the oversight of higher faculties? In 1985, a social psychologist named Robert Zajonc proposed a modern version of an old and out-of-date idea: Maybe movements of the face affected blood flow to the brain, he said. Perhaps contracting certain facial muscles to smile presses nearby veins in such a way that cooler blood is forced adjacent to the cortex, which in turn produces pleasure. Perhaps the act of frowning does the opposite.

Zajonc tried to prove his zany theory in the lab. In one study, he measured the temperature of subjects’ foreheads while they made different vowel sounds, ee and ü, for which their lips had to be in different postures. (The ü sound made their faces hotter, he reported, and put them in a foul mood.) In another, Zajonc put tubes into the noses of 20 undergraduates and pumped in air of different temperatures. (The students said the cool air made them feel the best.)

Around the time that Zajonc was pursuing this idea, Fritz Strack arrived at the University of Illinois and started doing research as a postdoc. He hadn’t planned to look at facial feedback, but he had some time to dabble. One day in a research meeting, in the spring of 1985, he and another postdoc, Leonard Martin, heard a presentation on the topic. Lots of studies found that if you asked someone to smile, she’d say she felt more happy or amused, and her body would react in kind. It appeared to be a small but reliable effect. But Strack realized that all this prior research shared a fundamental problem: The subjects either knew or could have guessed the point of the experiments. When a psychologist tells you to smile, you sort of know how you’re expected to feel.

The next day, Strack and his wife got in a car with Martin and his girlfriend, and the four of them set off on a road trip from Champaign-Urbana to New Orleans for Mardi Gras. Martin remembers they spent hours hashing out possible experiments. What if they could measure the effects of people’s smiles more covertly? What if the people they tested didn’t even know that they were smiling?

Other researchers had tried to pull off this deception. In the 1960s, James Laird, then a graduate student at the University of Rochester, had concocted an elaborate ruse: He told a group of students that he wanted to record the activity of their facial muscles under various conditions, and then he hooked silver cup electrodes to the corners of their mouths, the edges of their jaws, and the space between their eyebrows. The wires from the electrodes plugged into a set of fancy but nonfunctional gizmos.

Next Laird told the students that he needed them to tense and relax certain muscles. “Now I’d like you to contract these,” he’d say, tapping a subject’s brows. “Contract them by drawing them together and down.” Then he’d touch the same subject on either side of the jaw: “Now contract these. Contract them by clenching your teeth.” Step by step, he’d coax the subject’s face into expressions that he wanted—a glower, a grin, etc. In a later version of this experiment, Laird hooked up 32 undergrads to fake electrodes, and, after tricking them into frowning or smiling, he had them read and rate cartoons on a scale from 1 to 9, from “not at all funny” to “the funniest cartoon I ever saw.” When he tallied all the numbers, it looked as though the facial feedback worked: Subjects who had put their faces in frowns gave the cartoons an average rating of 4.4; those who put their faces in smiles judged the same set of cartoons as being funnier—the average jumped to 5.5.

Laird’s subterfuge wasn’t perfect, though. For all his careful posturing, it wasn’t hard for the students to figure out what he was up to. Almost one-fifth of them said they’d figured out that the movements of their facial muscles were related to their emotions.

Strack and Martin knew they’d have to be more crafty. At one point on the drive to Mardi Gras, Strack mused that maybe they could use thermometers. He stuck his finger in his mouth to demonstrate. Martin, who was driving, saw Strack’s lips form into a frown in the rearview mirror. That would be the first condition. Martin had an idea for the second one: They could ask the subjects to hold thermometers—or better, pens—between their teeth.

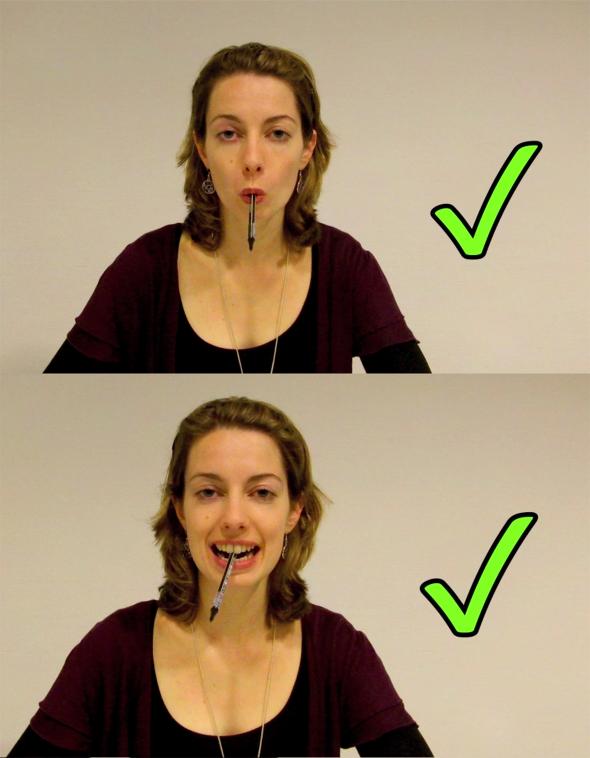

This would be the stroke of genius that produced a classic finding in psychology. When the subjects held the pens between their teeth, Strack and Martin realized, their mouths would be forced into ersatz smiles. When they held the pens between their lips, their mouths would be forced into frowns. The students wouldn’t even know that it was happening.

Courtesy of American Psychological Association. Used with permission. Source: Soussignan, R. “Duchenne Smile, Emotional, Experience, and Autonomic Reactivity: A Test of The Facial Feedback Hypothesis.”

Back in Illinois, Strack and Martin tried the same experiment as Laird but with pens in place of fake electrodes. They handed felt-tip markers to 92 undergrads and taught them how to hold them in their mouths. The experiment, they said, was meant to test the students’ “psychomotoric coordination” and how people with physical disabilities might learn to write or use the telephone. After the undergrads had done some practice tasks—using the pens for connect the dots and to underline the vowels on a page of random-printed letters—they were presented with a set of four single-panel comics from The Far Side and asked to rate their funniness.

The results matched up with those from Laird’s experiment. The students who were frowning, with their pens balanced on their lips, rated the cartoons at 4.3 on average. The ones who were smiling, with their pens between their teeth, rated them at 5.1. What’s more, not a single subject in the study noticed that her face had been manipulated. If her frown or smile changed her judgment of the cartoons, she’d been totally unaware.

“It was theoretically trivial,” says Strack, but his procedure was both clever and revealing, and it seemed to show, once and for all, that facial feedback worked directly on the brain, without the intervention of the conscious mind. Soon he was fielding calls from journalists asking if the pen-in-mouth routine might be used to cure depression. He laughed them off. There are better, stronger interventions, he told them, if you want to make a person happy.

Over the next two decades, many other labs adapted and extended his idea. One group stuck a pair of golf tees to its subjects’ eyebrows and had them touch the tips together, so as to force their brows to furrow. (This seemed to make the subjects sad.) Another taught people five different ways to hold a pencil in their mouths, so they could distinguish between the effects of, say, a polite, fake-looking smile and those of a more natural, eye-crinkling one. (The more authentic smiles seemed to make the subjects happier.)

Strack and Martin’s method would eventually appear in a bewildering array of contexts—and be pushed into the realm of the practical. If facial expressions could influence a person’s mental state, could smiling make them better off, or even cure society’s ills? It seemed so. In 2006, researchers at the University of Chicago showed that you could make people less racist by inducing them to smile—with a pen between their teeth—while they looked at pictures of black faces. In 2013, a Spanish team found that wearing a pen-in-mouth smile could make a person more creative in a picture-drawing task. And Strack himself would demonstrate that by getting students from his university to furrow their brows, he could bias them to think that celebrities weren’t really all that famous.

Indeed, the basic finding of Strack’s research—that a facial expression can change your feelings even if you don’t know that you’re making it—has now been reproduced, at least conceptually, many, many times. (Martin likes to replicate it with the students in his intro to psychology class.) In recent years, it has even formed the basis for the treatment of mental illness. An idea that Strack himself had scoffed at in the 1980s now is taken very seriously: Several recent, randomized clinical trials found that injecting patients’ faces with Botox to make their “frown lines” go away also helped them to recover from depression. According to proponents of the facial-feedback theory, these studies show that merely losing the ability to pout can force improvement to a person’s mood.

Looking back across these years of follow-up research, including the success of facial feedback in the clinic, Strack found himself with little doubt about the field. “The direct influence of facial expression on judgment has been demonstrated many, many times,” he told me. “I’m completely convinced.”

That’s why he volunteered to help the skeptics in that email chain three years ago. “They wanted to replicate something, so I suggested my facial-feedback study,” he said. “I was confident that they would get results, so I didn’t know how interesting it would be, but OK, if they wanted to do that? It would be fine with me.”

* * *

The psychologist in charge of the facial-feedback replication project, E. J. Wagenmakers of the University of Amsterdam, has no special interest in emotion or in the study of expressions. “My interest is mainly methodological,” he told me—which is, I think, another way of saying that he makes a living as a critic of the methods used in his field. “Science is done by humans,” he said, “and humans are susceptible to all kind of biases. I think there’s a good reason for skepticism across the board.”

Still, when Fritz Strack offered up his 1988 paper for closer scrutiny, Wagenmakers thought the odds of a successful replication were pretty good. He ticked off a list of reasons why: The finding had a lot of history behind it, going back to James and Darwin; it seemed plausible on its face; other research seemed to back it up. “Personally, I felt that this one actually had a good chance to work,” he said.

How good a chance?

“I gave it a 30-percent shot.”

Lisa Larson-Walker

In a sense, he was being optimistic. Replication projects have had a way of turning into train wrecks. When researchers tried to replicate 100 psychology experiments from 2008, they interpreted just 39 of the attempts as successful. In the last few years, Perspectives on Psychological Science has been publishing “Registered Replication Reports,” the gold standard for this type of work, in which lots of different researchers try to re-create a single study so the data from their labs can be combined and analyzed in aggregate. Of the first four of these to be completed, three ended up in failure.

In March I wrote about the recent RRR for “ego depletion,” or the idea that self-control functions like a muscle that can be worked into exhaustion. There was plenty to feel good about—evidence for the effect had been produced hundreds of times before, in lots of different ways. But there were questions, too. Many of the findings seemed outlandish, like the claim that you could replenish your supply of willpower by drinking a glass of lemonade. Two groups of scientists had tried to analyze all the research in the field and came to opposite conclusions: One found a significant effect; the other detected very little. So it wasn’t altogether unexpected when the replicators came out with their findings: “Nada. Zip. Nothing.”

The work on facial feedback, though, had never been a target for the doubters; no one ever tried to take it down. Remember, Strack’s original study had confirmed (and then extended) a very old idea. His pen-in-mouth procedure worked in other labs. That’s not to say that he proposed it on the email chain without reservations. In fact, he’d offered several caveats: First, it wasn’t relevant to social priming, which had been the focus of the emails up until that point; and second, he acknowledged that the evidence from the paper wasn’t overwhelming—the effect he’d gotten wasn’t huge. Still, the main idea had withstood a quarter-century of research, and it hadn’t been disputed in a major, public way. “I am sure some colleagues from the cognitive sciences will manage to come up with a few nonreplications,” he predicted. But he thought the main result would hold.

Within a month of his volunteering, Strack had sent all the materials from the 1980s, including the original cartoons, to Wagenmakers. It took another two years to get the project ready. With the help of two assistants, Titia Beek and Laura Dijkhoff, Wagenmakers had to work out each and every aspect of the study and post it in a public forum. They figured out the wording that would be used to introduce their experiment (“You are participating in a study on psychomotoric coordination …”), what kinds of pens the researchers would put into the subjects’ mouths (Sharpies or Stabilo Pen 68s), which cartoons to show the subjects (a new set of single-panel comics from The Far Side), and exactly how they planned to analyze the data.

In April 2015, the experiment began. Wagenmakers’ group had signed up scientists from 17 labs spanning eight countries, so that each could try to re-create Strack’s original procedure. In total the group would test nearly 2,000 subjects. There were several updates to the method: Now the subjects would receive their instructions from prerecorded videos, since talking to the researchers might have biased them in subtle ways; and the subjects would be recorded as they went through the experiment, so the researchers could check that they were holding the pens correctly.

It took another 16 months of part-time work to collect the data, run analyses, write the paper, and finish up the editing.

The results came out on Aug. 18. They weren’t good.

Beek, Dijkhoff,Wagenmakers, and Simons

In one-half of the participating labs (nine of 17, to be exact), the subjects who were smiling gave slightly higher average ratings to the cartoons—they reported feeling one- or two-tenths of a point more amused, on the 10-point rating scale. (In Strack’s original study, the difference between the smilers and frowners had been much bigger, 0.82 points.) In the data from the other labs, the effect seemed to go the other way: The smiling subjects rated the cartoons as one- or two-tenths of a point less amusing. When Wagenmakers put all the findings in a giant pile, the effect averaged out and disappeared. The difference between the smilers and frowners had been reduced to three-hundredths of a rating point, a random blip, a distant echo in the noise.

“I really had a hope that this one would actually work,” Wagenmakers says. “Unfortunately, it didn’t turn out that way.”

* * *

Fritz Strack has no regrets about the RRR, but then again, he doesn’t take its findings all that seriously. “I don’t see what we’ve learned,” he said.

Two years ago, while the replication of his work was underway, Strack wrote a takedown of the skeptics’ project with the social psychologist Wolfgang Stroebe. Their piece, called “The Alleged Crisis and the Illusion of Exact Replication,” argued that efforts like the RRR reflect an “epistemological misunderstanding,” since it’s impossible to make a perfect copy of an old experiment. People change, times change, and cultures change, they said. No social psychologist ever steps in the same river twice. Even if a study could be reproduced, they added, a negative result wouldn’t be that interesting, because it wouldn’t explain why the replication didn’t work.

So when Strack looks at the recent data he sees not a total failure but a set of mixed results. Nine labs found the pen-in-mouth effect going in the right direction. Eight labs found the opposite. Instead of averaging these together to get a zero effect, why not try to figure out how the two groups might have differed? Maybe there’s a reason why half the labs could not elicit the effect.

“Given these eight nonreplications, I’m not changing my mind. I have no reason to change my mind,” Strack told me. Studies from a handful of labs now disagreed with his result. But then, so many other studies, going back so many years, still argued in his favor. How could he turn his back on all that evidence?

In a written commentary published with the replication report, Strack singled out what he sees as problems with the study. First of all, more than 600 subjects had to be excluded from analysis, about one-quarter of the total pool. According to the RRR, subjects were excluded when they held the pens incorrectly, or gave wildly divergent ratings to the cartoons. But Strack wondered if the other subjects, many of them psychology students, might have guessed the purpose of the research. After all, they were re-enacting a classic study in the field.

He also wondered if the Far Side cartoons, which were “iconic for the zeitgeist of the 1980s,” would “instantiate similar psychological conditions” in undergraduates circa 2015. Gary Larson stopped drawing the comic in 1995. Strack said he’d raised this point with Wagenmakers at the very start of the project, but his concern had been ignored. (The RRR team did pre-test a panel of cartoons on 120 students at the University of Amsterdam, to make sure they would be rated about as funny as the ones from Strack’s original experiment, and they were.)

Then there were the cameras, which might have made the subjects so self-conscious, Strack proposed, that they ended up suppressing their emotions. And finally, he wondered if the spread of findings from the 17 labs showed evidence of bias. The ones with bigger samples, he said, seemed to find more positive results. It was as if the replicators had thumbed the scales against the pen-in-mouth effect. (Joe Hilgard, a meta-analysis expert at the University of Pennsylvania, examined this idea and found it unconvincing.)

Leonard Martin agrees with Strack’s concerns and says the replicators didn’t fully follow their procedure. The work was so sloppy, he argued via email, that “the real story here may not be about the replicability of the pen in the mouth study or the replicability of psychology research in general but about the current method of assessing replicability.” Given that such efforts can alter established findings in the field and tarnish people's reputations, he said that “Project Replication” should be very careful: “If the current lack of rigor continues, then psychology may find itself in its own version of the McCarthy era.”

Strack had one more concern: “What I really find very deplorable is that this entire replication thing doesn’t have a research question.” It does “not have a specific hypothesis, so it’s very difficult to draw any conclusions,” he told me. “They say the effect is not true, but I don’t know what that means. Maybe we have learned that [the pen-in-mouth procedure] is not a strong intervention. But I never would have claimed that it is.”

The RRR provides no coherent argument, he said, against the vast array of research, conducted over several decades, that supports his original conclusion. “You cannot say these [earlier] studies are all p-hacked,” Strack continued, referring to the battery of ways in which scientists can nudge statistics so they work out in their favor. “You have to look at them and argue why they did not get it right.”

So I took Strack’s advice and went back to his article from 1988, to see if I might find any reason why the research would have gone amiss. The paper included the results from two related experiments: For the first, Strack and Martin had the students hold the pens in the teeth or lips and rate the cartoons on their funniness. That’s when they found the difference of 0.82 rating points between the smilers and the frowners.

But the psychologists weren’t yet convinced they had a real result, and they kept the data from their boss, the social psychologist Robert Wyer. “We did not dare to tell him because he would have said ‘you’re crazy,’ ” remembers Strack. Instead they waited until Strack had a chance to try another version of the same experiment, one their paper would describe as an attempt “to strengthen the empirical basis of the results and to substantiate the validity of the methodology.” In other words, Strack set out to replicate himself.

For the second version, Strack added a new twist. Now the students would have to answer two questions instead of one: First, how funny was the cartoon, and second, how amused did it make them feel? This was meant to help them separate their objective judgments of the cartoons’ humor from their emotional reactions. When the students answered the first question—“how funny is it?,” the same one that was used for Study 1—it looked as though the effect had disappeared. Now the frowners gave the higher ratings, by 0.17 points. If the facial feedback worked, it was only on the second question, “how amused do you feel?” There, the smilers scored a full point higher. (For the RRR, Wagenmakers and the others paired this latter question with the setup from the first experiment.)

In effect, Strack had turned up evidence that directly contradicted the earlier result: Using the same pen-in-mouth routine, and asking the same question of the students, he'd arrived at the opposite answer. Wasn’t that a failed replication, or something like it?

Strack didn’t think so. The paper that he wrote with Martin called it a success: “Study 1’s findings … were replicated in Study 2.” In fact, it was only after Study 2, Strack told me, that they felt confident enough to share their findings with Wyer. He said he’d guessed that the mere presence of a second question—“how amused are you?”—would change the students’ answers to the first, and that’s exactly what happened. In Study 1, the students’ objective judgments and emotional reactions had gotten smushed together into one response. Now, in Study 2, they gave their answers separately—and the true effect of facial-feedback showed up only in response to the second question. “It’s what we predicted,” he said.

That made sense, sort of. But with the benefit of hindsight—or one could say, its bias—Study 2 looks like a warning sign. This foundational study in psychology contained at least some hairline cracks. It hinted at its own instability. Why didn’t someone notice?

* * *

How bad is this latest replication failure? It depends on your demeanor. If you read the study in an optimistic mood—let’s say, with a highlighter in your teeth and your lips pulled back into a smile—then perhaps you’d be inclined to think it’s just a local problem. Maybe there was something off about The Far Side cartoons, or the presence of the cameras, or the subject pool. In any case, you’d think the replication failure tells us this and only this: For one reason or another, one particular re-creation of one particular experiment, designed on the way to Mardi Gras in 1985, simply didn’t work.

Or maybe you’re inclined to take a slightly darker view of the research: It could be there was something wrong with the original paper. Maybe the pen-in-mouth approach had a fatal flaw, even one that might come up in every other study where it’s used. Now your forehead starts to crease with worry: What if there’s a deeper problem, still? They only did an RRR for this one specific work, but it was chosen precisely on account of its fame and influence. If the classic facial-feedback paper doesn’t replicate, then who’s to say that any other, lesser facial-feedback research would? Maybe there’s a problem with the whole idea that expressions have a direct effect on our emotions. Maybe Darwin had it wrong!

What if all that work on facial feedback suffers from the file-drawer effect? When scientists come up with data in support of Strack’s result, they went ahead and published it; otherwise, they keep it to themselves. If that’s the case then all those follow-up results that Strack has cited might be bogus, too. Even the randomized clinical trials—the ones that found that Botox cures depression—could be fishing expeditions hauling in red herrings: Maybe Botox made people happier simply because they started feeling good about their looks. Or maybe other people started acting nicer to them since they weren’t frowning all the time.

Now put that highlighter between your lips and tell me what you see: Four of five RRRs have come up with no effect. It doesn’t really matter which effect they’re studying—almost every major replication project ends in failure. If facial feedback seems a little suspect, then what about those other findings in embodied cognition—things like power pose and the Lady MacBeth effect? (Spoiler: both of those have failed in replications, too.) Is all of psychology at risk? What about cognitive neuroscience? What about every other field of scientific research?

That’s the crux of the replication crisis. No one knows precisely how to calibrate their level of disquiet.

Here’s a question that I’ve often asked, while reporting on these issues: How much should we be worried by this latest null result? Or in plainer terms: Level with me, doc—how bad is it?

Scientists are soothing types. They don’t like to get worked up. “I think there’s a danger in overgeneralizing,” said Daniel Simons, a psychologist at the University of Illinois and one of the editors of the RRRs. It’s true you would have been mistaken if you’d drawn broad conclusions from Strack’s original result. But then, you might be just as wrong to draw overbroad conclusions from the failure to replicate that one result. If anything, he said, the exercise should make us into skeptics, not doomsayers.

The problem is, there isn’t much reward for being a skeptical psychologist. If you want to get attention for your work, both from the press and from your peers, then you’d better find a way to gin up dramatic, unexpected data. “That’s another way of saying that your finding is implausible or unlikely to be true,” Wagenmakers said. He laid the blame for that in part on scientific journal editors, who set the bar too high for solid, incremental research. But he also implicated journalists. We’re the ones who highlight the shabbiest research. Our attraction to absurd results (e.g., more people die in hurricanes with girls’ names) or those that can be fit into a flimsy costume of self-help create the wrong incentives in the field. It tells the researchers that their weakest findings count the most.

Journalists are also drawn to conflict. I know it would be more dramatic and surprising—and a better story for my readers—if each new, failed replication revealed another sign of the apocalypse. I’ll confess that I’m incentivized to put this latest RRR into a narrative of ruination, or a war between the old guard and the new, or a tidal wave of doubt that’s washing over all of science. I know I’ll get more clicks if I suggest that facial feedback has been debunked, or that everything you thought you knew about emotions turns out to be wrong. I know it would be more entertaining if I argued that the psychology is going up in flames.

If bad incentives created this crisis, then bad incentives could exaggerate its scale.

* * *

Among the cartoons from The Far Side that were used in this month’s replication is one that first appeared in newspapers in October 1988, just a few months after Strack published his pen-in-mouth study. It shows three goldfish perched beside a fishbowl that has somehow caught on fire. One of the goldfish says to the others: “Well, thank God we all made it out in time. … ‘Course, now we’re equally screwed.”

I had those fish in mind when I talked to E.J. Wagenmakers. Given all the recent news, I ventured, it seems like it might be reasonable to experience some panic and regret.

“I would agree,” he said. “It is sad, but that’s in the past. We have to look forward, and I think there’s actually a lot of progress possible.” He elaborated over email: Journals are changing their policies; transparency is on the rise; funding agencies have started paying for replication research. Certain woke psychologists have even started auditing their own research, to make sure it’s getting more reliable. “The field is going through a metamorphosis,” Wagenmakers wrote, “or a revolution if you like.”

A lot has changed in recent years, even as the replication failures pile up, and there’s ample cause for optimism. When ego depletion appeared to bite the dust in March, a researcher in that field, Michael Inzlicht, suggested to me that it might soon be time to start over: “At some point we have to start over and say, This is Year One,” he said, sounding hopeful in a way.

My biases have been declared—they’re preregistered above—but I can’t stop myself from worrying that we’re at the point where the goldfish have just escaped their burning bowl. They’ve dodged a great catastrophe, and they’re looking toward the future.

But what about the past? The potential damage from the replication crisis goes in both directions. Even if we fixed the problem going forward, even if we did away with all the p-hacking, the publication bias and the pseudo-fraud in social science, then we’d still be gazing back into a murky pool of published research. These replication efforts teach us how to do good science but also that the history of research is full of toxic waste. Merely pointing in its direction doesn’t clean it up. Whatever happens now, that remains a catastrophic revelation. Findings of the past form the substrate for the scientific enterprise—they’re how it lives and how it grows, with new ideas emerging from the limpid swirl of those that came before. Now we know the waters are polluted, and there’s no efficient way to filter them.

I mean, it’s great that psychologists have identified their problems. It’s great that they’re starting to confront them. It’s great they figured out that they were in a Cuyahoga River fire of questionable results, and it’s great they all made it out in time.

‘Course, when you think about it, aren’t they equally screwed?

Lisa Larson-Walker