The New Culture of Life

In the era of Trump and Whole Woman’s Health, the future of pro-life activism is young, female, secular, and “feminist."

Kelsey Hazzard

If you are a pro-life activist, you have several reasons to be discouraged at the moment. Antonin Scalia, the Supreme Court’s most vociferously anti-abortion justice, died in February. Then in June, in Whole Woman’s Health v. Hellerstedt—the most sweeping abortion decision since 1992—the court struck down parts of a 2013 Texas law that placed strict restrictions on abortion clinics under the guise of women’s health and safety; similar laws in Alabama, Mississippi, and Wisconsin rapidly fell in the wake of the 5–3 vote. As the Catholic writer Michael Brendan Dougherty summed it up this summer, “2016 is turning out to be the worst year for the pro-life cause in at least a generation.”

Normally, an election season would bring the promise of a restart: the possibility of a Republican ally in the White House, and a Supreme Court justice or three following in his wake. But Republican nominee Donald Trump called himself “very pro-choice” as recently as 1999 and has been downright incoherent on the issue during the past year. Even if you believe his conversion to the anti-abortion cause, he has shown almost no grasp of its language or the ideas behind it. As evangelical writer Matthew Lee Anderson put it in July in an essay titled “There Is No Pro-Life Case for Donald Trump,” Trump is “someone who in his personal life has not merely lived in, but reveled in the moral atmosphere and commitments that stand beneath our abortion culture.” The video made public on Friday of Trump boasting about sexual assault was just a visceral reminder of a well-known truth: The Republican candidate’s private moral code is built on what you might call anti–family values.

Despite recent setbacks, however, the demographic outlook for the pro-life movement looks anything but bleak. On issues from race to sexuality to drug law, Americans are used to seeing each new generation become more progressive than their parents; with abortion, it’s not happening: In a 2015 Public Religion Research Institute survey, 52 percent of millennials said the label “pro-life” describes them somewhat or very well, a number that roughly mirrors the general population. A 2013 poll showed that 52 percent of people aged 18 to 29 favored bans on abortion after 20 weeks, compared with 48 percent overall. Pro-choice activists now worry about the “intensity gap” among young people: A poll commissioned by NARAL Pro-Choice America in 2010 found that 51 percent of anti-abortion voters younger than 30 considered the issue “very important,” but for pro-choice voters the same age, only 26 percent said the same.

With these numbers in mind, it’s possible that the pro-life movement is in a moment of transition, not retreat. This impression is only reinforced by talking to the leaders of the movement’s next generation, who look very little like their elders. In conversations over the past several weeks with activists and other young people who care deeply about ending abortion, I found many who are skeptical of the movement’s long-held ties to the GOP and the Christian right. Instead, they are using the language of feminism, human rights, and the Black Lives Matter movement to make their case for a new culture of life.

“There’ a little bit of truth to the old pro-choice saying that the movement is a bunch of old conservative white men,” activist Aimee Murphy told me. “But I really have seen a massive shift with the youth, to ensure that our solutions are women-centered and that we’re being consistent and nonpartisan, inclusive and opening and welcoming.”

* * *

Aimee Murphy

Murphy was a pro-choice 16-year-old in California when an abusive, on-off boyfriend raped her. When the rape resulted in a pregnancy scare, Murphy’s rapist wanted her to get an abortion, and threatened to kill her and himself if she didn’t. A decade later, she still chokes up when she talks about that time in her life. But the threat was also clarifying. “In that moment, something clicked,” she said. “I could not use violence to get what I wanted in life. I realized that if I were to get an abortion, I would just be passing oppression on to a child.”

And why music in politics matter, according to the Political Gabfest. Listen to this special Slate Plus bonus segment by joining us today — your first two weeks are free.

Now 27, Murphy is the founder of the Pittsburgh-based nonprofit Life Matters Journal, which describes itself as a “human rights organization dedicated to bringing an end to aggressive violence.” The organization and its flagship publication oppose abortion as well as torture, the death penalty, and “unjust war.” Murphy believes that the modern conservative movement doesn’t grasp what she calls the “intrinsic worth” of every human life, echoing Catholic theology. “And if they do understand it,” she said, “they’re making a lot of exceptions.”

Life Matters Journal: Volume 5–Issue 2, July 2016

Life Matters Journal’s slate of ethical and political stances is very similar to official positions of the Catholic Church. In particular, it echoes the “consistent life ethic,” a concept promoted by Chicago Cardinal Joseph Bernardin starting in the early 1980s, which began with the premise that all life is sacred. But many young pro-life activists, even if they are Catholic—and many are—prefer not to frame their arguments as religious. The Southern Baptist co-president of Harvard’s pro-life club, Will Long, told me that talking about “intrinsic human rights” is a way to open up conversations about the morality of abortion with students who aren’t religious. “Human rights” was a phrase I heard over and over from the young activists I spoke to.

The pro-choice movement has long framed access to abortion as a human right; pro-life advocates have been able to borrow that language thanks in part to technology. When Tina Whittington, now the executive vice president of Students for Life of America, got started in pro-life activism in the 1990s, she held signs depicting aborted fetuses outside abortion clinics. The premise of this notoriously confrontational approach was that to see a fetus’s fingers and toes, or its tiny profile, would provoke a kind of awakening: This can’t be just a “clump of cells,” to borrow from pro-choice rhetoric, because it looks just like a baby. Today, though, ultrasound images—including incredibly precise three-dimensional sonograms—are widely available and shared heavily on social media.

“The millennial generation has had access to the womb,” Whittington said. “A lot of young people have seen those images, and realize that there’s a baby, and it’s a human being.” On college campuses, according to Whittington, many pro-choice students acknowledge that the fetus is a form of human life—even if they believe the mother deserves preference—or that a fetus exists on a kind of continuum of life that still makes abortion morally acceptable within a prescribed time frame. “It’s more of a nuanced discussion now,” she said.

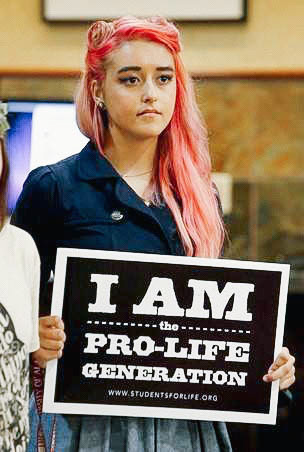

Kelsey Hazzard

It’s also an increasingly nonreligious one. In her talks on college campuses, activist Kelsey Hazzard, founder of the organization Secular Pro-Life, likes to point out that millennials are both the “pro-life generation” and the least religious generation. The 2013 Pew survey showed that 25 percent of nonreligious Americans believe having an abortion is morally wrong; as the nonreligious population, or “nones,” continues to grow, the number of pro-life “nones” will grow, too. A 2014 Pew survey found that 18-to-29-year-olds make up a disproportionate 39 percent of anti-abortion “nones.”

But these would-be activists had trouble finding each other without church-based institutions to coalesce around, according to Hazzard, 28, who works by day as a civil litigation attorney in Naples, Florida. She started Secular Pro-Life as a student at the University of Miami, initially just as a place for nonreligious pro-lifers to connect online. Although Christian churches served as convenient organizational bases for the first decades of activism in the post–Roe v. Wade era, those spaces can be alienating to nonbelievers who might be otherwise sympathetic to the anti-abortion message. Hazzard sees the internet as an alternative infrastructure for the next generation of pro-life activists, who have different moral assumptions and different political concerns than the old-school Christian right. “We've been in the process over the last five to 10 years of a baton-passing,” she said. “I think as that process continues, and particularly as people drop the same-sex marriage issue—please—and focus on life issues, that will be the cultural shift.” That shift involves a pivot to “human rights arguments” as opposed to Bible-based ones, she says.

Tommy L. Oswalt

Maria Oswalt, a 22-year-old senior at the University of Alabama who leads the campus’ Students for Life chapter, gets frustrated when pro-life advocates vocally oppose, say, transgender bathroom bills—the kind of issue that she sees as having no inherent connection to abortion and that serves only to make the movement look intolerant. Her Students for Life chapter focuses on abortion, but it also opposes the death penalty and assisted suicide; Oswalt sees these issues as naturally connected to abortion in a way that gender and sexuality are not. “Let’s just focus on life issues, and not try to pull these other nonrelated issues into it,” she said.

As Murphy and others told me, moral consistency matters a great deal to their younger compatriots in the movement, whose pro-life ethic means concern for life “from womb to tomb.” “It’s not a partisan issue, it’s not a religious issue,” Murphy said. “It’s a human rights issue.”

* * *

One stereotype of the pro-life movement is that it is dominated by men, and old men at that. Last year, when the popular conservative site Newsmax compiled a list of the Top 100 most influential pro-life advocates, only five of the Top 20 were female, and one of those was the soon-to-pass-away Phyllis Schlafly. But that’s starting to change. There’s Kristan Hawkins, the 31-year-old president of Students for Life of America. Lila Rose, now 28, is the founder of Live Action, a brash organization that has produced several news-making exposés of Planned Parenthood; Rose is now arguably the most famous young pro-lifer in America. (David Daleiden, the 27-year-old who filmed last year’s undercover video of a Planned Parenthood executive discussing tissue donation, got his start at Live Action.) The Susan B. Anthony List, Concerned Women for America, and the National Right to Life Committee are among the other prominent groups led by women. Many of the campus leaders and other young activists I spoke with are women.

Women aren’t just leading the next generation of the pro-life movement—many of them are doing it using the language of feminism, which would have been anathema to the old guard of pro-life activists. If you believe, as sociologist Kristin Luker suggested in her influential 1984 book Abortion and the Politics of Motherhood, that opposing abortion is really just a stealthy way of controlling women, the notion of an anti-abortion feminism will sound either absurd or morally outrageous. But the idea that pro-lifers are simply out to oppress women was always an oversimplification, and it’s especially imprecise as a description of the next generation of activists.

Destiny Herndon-De La Rosa

Destiny Herndon-De La Rosa, who is 33 and lives in Dallas, does not fit the stereotype of a pro-life activist: She has neon pink hair, and she calls activists who use graphic posters of aborted fetuses “the turd in the Kool-Aid.” She founded New Wave Feminists in 2007 because she “wanted to see a change not only in the feminist movement, but in the pro-life movement.” Herndon-De La Rosa wants to smash the patriarchy, but she sees it in unexpected places: in “douchebags” who “treat fertility like a disease” by expecting their partners to be on chemical birth control and to get an abortion if they do get pregnant, for example. “I don’t understand how more radical feminists don’t see that,” she said.

Murphy likes to say that the future of the pro-life movement is feminist, and the future of the feminist movement is pro-life. “I see this movement going in a direction that is a lot more women-centered,” she said. “What are we doing to help women in need? What are we doing to empower women? What are we doing to promote equality among all persons?” The fact that women are expected to bear the consequences of pregnancy alone, and that pregnancy often seems incompatible with success, is “a grave form of injustice that we are passing on to women,” she said.

Students for Life of America, the largest group of campus pro-life clubs, launched an initiative in 2011 to support pregnant women on college campuses by connecting them with resources like health care and housing and by informing them of their Title IX rights. “For us, it’s not just about her choosing life, although of course that is our passion,” executive vice president Whittington said. “But it’s also about seeing her finish school, because we know the No. 1 segment of our population that’s at or below poverty level is single mothers.”

Molly Hurtado

Christina Bennett, an activist in Connecticut, works full time at a “crisis pregnancy center,”; these types of center, as Nora Caplan-Bricker put it earlier this year in Slate, “exist to prevent women from getting abortions.” According to Bennett, the pro-life movement needs to do a better job speaking to young black women such as herself. Like the Black Lives Matter movement, she says, the pro-life cause is fundamentally about protecting a vulnerable population. “I really want to be able to reach the African American community with a message of life as a human rights issue and a civil rights issue,” she said. “This is a message that appeals to African Americans because we know what it’s like to be victimized, to be looked down upon.” At the same time, she questions the motives and sincerity of some pro-life activists who have appropriated the rhetoric of Black Lives Matter. (“If Black Lives Matter, Protest Planned Parenthood,” read a headline on the leading pro-life news site Life News in July.) “If you’re a person who’s saying, ‘I care about black babies in the womb,’ and then you see Tamir Rice, you see Mike Brown, and your first response is that the black community doesn’t really care because they’re aborting all their babies—if that’s your first response, then something is missing,” Bennett said. “You’re not showing empathy.”

* * *

Drew Angerer/Getty Images

With just about a month until Election Day, Trump has successfully dragged the old guard of anti-abortion activists to his side, however belatedly and begrudgingly. “The pro-life movement has officially joined the Trump train,” the Daily Beast reported recently as the candidate launched his Pro-Life Coalition, headed by an activist who once urged Republicans primary voters to support “anyone but Donald Trump.” Many of Trump’s defenders among the religious right have stuck by him even in the wake of the leaked Access Hollywood video. In reiterating his loyalty on Monday, Focus on the Family founder James Dobson emphasized Trump’s “promises to support religious liberty and the dignity of the unborn.”

But the movement’s next generation have not been so easily co-opted. For the first few weeks of my reporting, I struggled to find a single young pro-life voter who would talk to me about supporting Trump. Over time, they trickled in: the Chicago activist who said at least Trump seems to realize he needs pro-lifers on his side; the Virginia college student who said it was worth it because Trump might tilt the Supreme Court against abortion rights.

“When you consider what pro-lifers believe abortion is, which is essentially the systematic killing of millions of children every year, that’s an issue of some national importance,” said Long, the co-president of Harvard Right to Life. “If Clinton gets this nomination, you know that essentially our generation is not going to fix Roe v. Wade.” Even with those stakes, Long would only say he is “tentatively” leaning toward Trump. (He confirmed Monday that the Access Hollywood tape had not changed that.)

Many of the activists and voters I spoke with feel a visceral disgust toward the Republican nominee. Many told me that abortion is important to them because they believe all human life is valuable; this idea is not one that fits with Trump’s worldview. Long’s co-president, Maria McLaughlin, says she abhors Trump’s obsession with building a wall between the U.S. and Mexico; Herndon-De La Rosa is appalled by his misogyny. Trump may have “converted” to being pro-life, many activists told me, but as Hazzard puts it, “tying the pro-life brand to the Trump brand is just totally incompatible and disastrous. Anyone who has supported Trump or even been silent on the matter is going to have no credibility going forward, particularly among young people.” Secular Pro-Life broke from its own tradition and denounced Trump in the primaries, a condemnation it has not revoked in the general election.

Secular Pro-Life

Does Trump’s sanity-threatening candidacy create an opening for Democrats to capture the next generation of pro-life voters? It’s tempting to think so: A young pro-lifer who also thinks of herself as an antiwar feminist is not an otherwise traditional Republican voter.

Still, few young pro-lifers I spoke to felt comfortable voting for Hillary Clinton. They are disturbed by her support for legal late-term abortion and for repealing the Hyde Amendment, which bars federal funds from being used to pay for abortion. The Democratic platform adopted at the convention in July is more strongly in favor of abortion rights than ever. That makes the Republican Party the only quasi-reasonable place for committed pro-life voters. “There are a lot of times I wish the Democrats would give up their dogged and relentless support for abortion,” Matt Yonke, the assistant communications director of the Pro-Life Action League, told me by email. “I think they’d be surprised how many people might switch parties if it weren’t for this issue. Welfare programs, gun laws, taxes—all the things conservatives are known for caring about—don’t matter at all to me and many serious pro-lifers I know.”

Some pro-life thinkers have yearned for a new “party of life” that would embrace both anti-abortion policies and traditionally Democratic family policies such as increased child-tax credits and tax credits for corporations with family-friendly policies. With the recent legislative and judicial setbacks, however, many in the “pro-life generation” find themselves wondering whether politics are even going to be their path to victory. “The pro-life message is not about who’s president or about legislation; it’s about cultural change,” Herndon-De La Rosa said. “If we can learn anything from the LGBTQ movement, they changed the culture and the laws followed. ... Ultimately abortion is going to be the same thing. We have to humanize the child. People have to understand this is a human being with their own bodily autonomy.” That argument is, she stressed, “completely a feminist message.”

Whittington looks back further in history for inspiration. She mentions Buck v. Bell, a 1927 Supreme Court case that ruled that compulsory sterilization of the “unfit” was constitutional; it has never been overturned, although the practice is now rightly viewed as repugnant. Whittington sees a lesson there: A movement doesn’t need to change the law if it can change enough people’s minds. “I don’t know if we’re ever going to overturn Roe v. Wade,” she said. “But our culture can move past it.”