The Trapdoor of Trigger Words

What the science of trauma can tell us about an endless campus debate.

Photo illustration by Natalie Matthews-Ramo. Photos by Thinkstock.

As educators and students suited up for the fall semester last month, University of Chicago dean of students John Ellison sent a provocative letter to incoming freshmen about all the cushioning policies they should not expect at their new school. “We do not support so-called ‘trigger warnings,’ we do not cancel invited speakers because their topics might prove controversial, and we do not condone the creation of intellectual ‘safe spaces’ where individuals can retreat from ideas and perspectives at odds with their own,” Ellison wrote.

Ellison’s pre-emptive strike against trigger warnings, or alerts that professors might stamp on coursework that could provoke a strong emotional response, was the latest salvo in a yearslong and stormy conversation on college campuses—a kind of agon between “free speech” and “safe spaces.” The University of Chicago missive seemed to plant a flag in the former camp, declaring itself a Political Correctness Avenger, its cape of First Amendment verities fluttering in the wind.

Its side of the debate insists that students have embraced an ethos of personal fragility—that they are infantilizing themselves by overreacting to tiny slights. A splashy Atlantic cover story from September 2015 on the “coddling of the American mind” argued that universities were playacting at PTSD, co-opting the disorder’s hypersensitivity and hypervigilance. The other side protests administrators’ lack of awareness of marginalized groups; these students say they seek more inclusive, responsive, and enlightened spaces for learning. For them, the “tiny slights” have a name—microaggressions—and a high cost. They accumulate like a swarm of poisonous bee stings. As one outgoing college senior at American University told the Washington Post in May, “I don’t think it’s outrageous for me to want my campus to be better than the world around it. … I think that makes me a good person.”

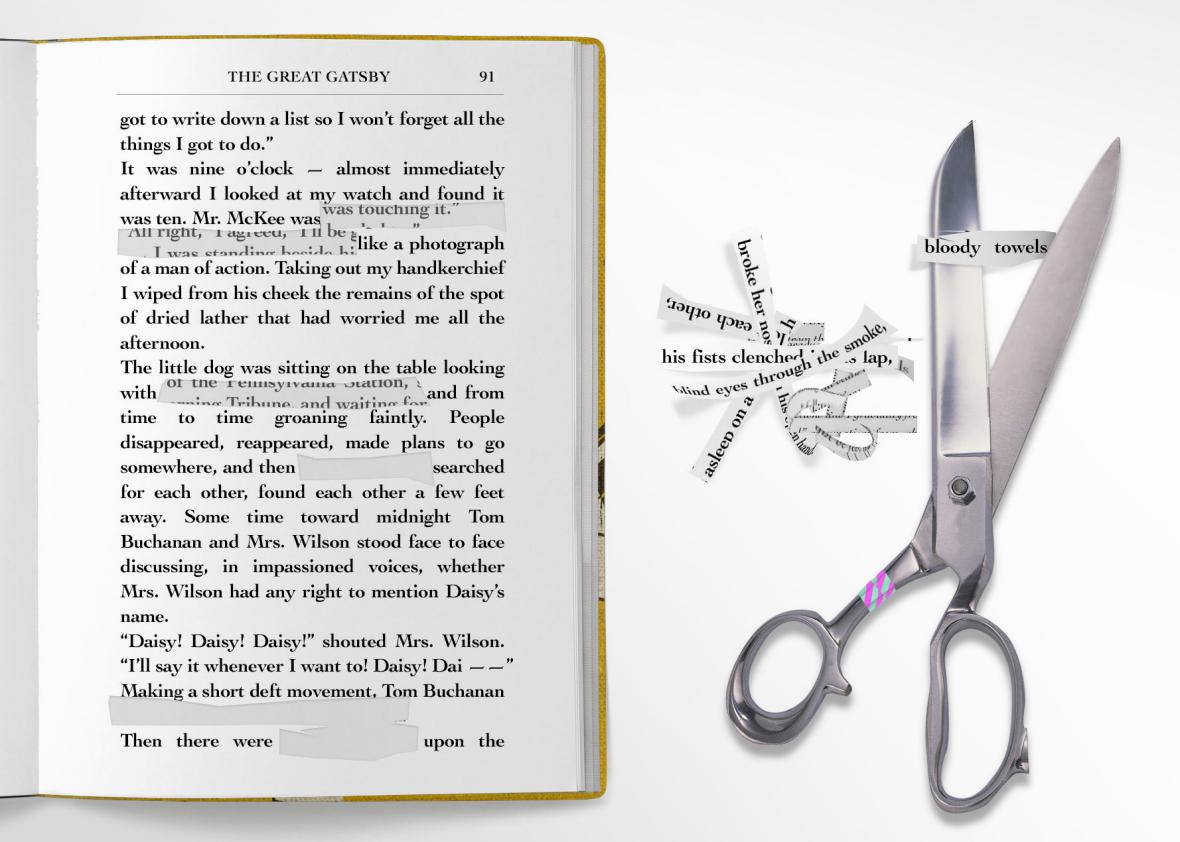

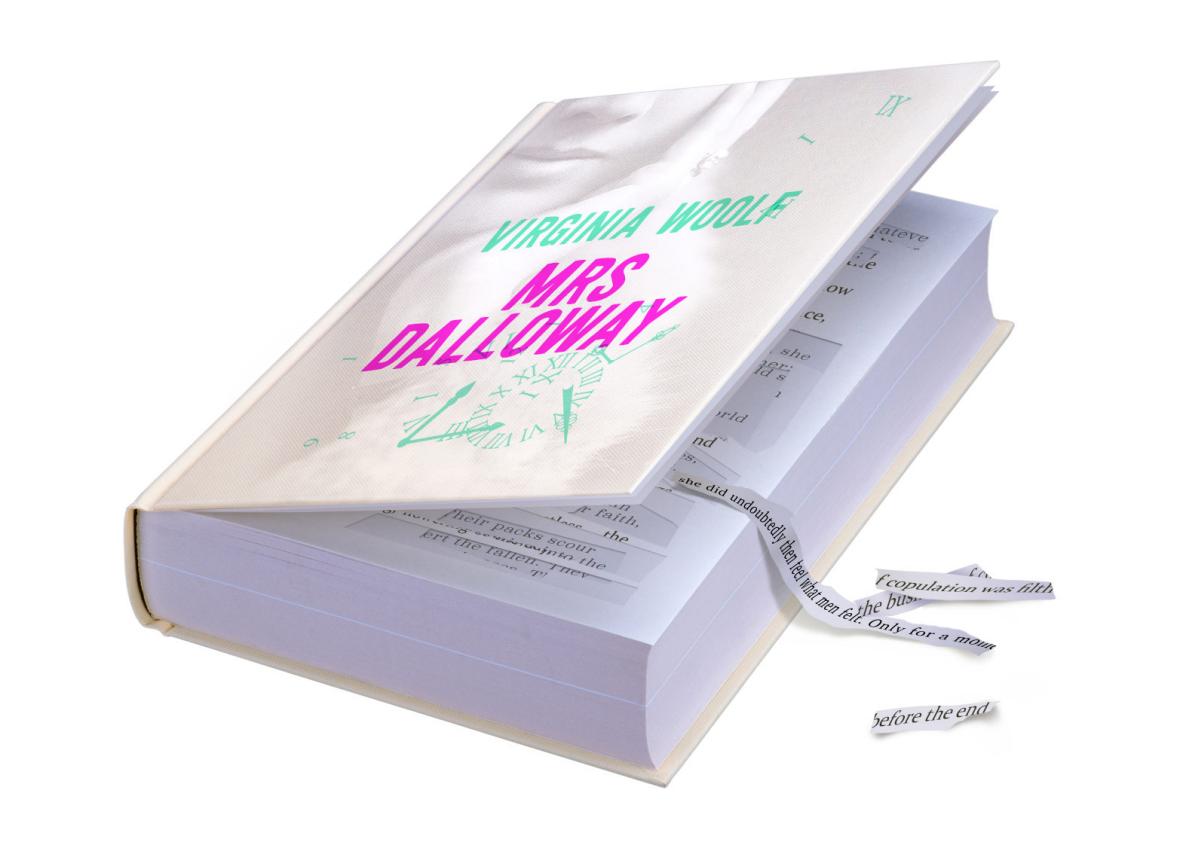

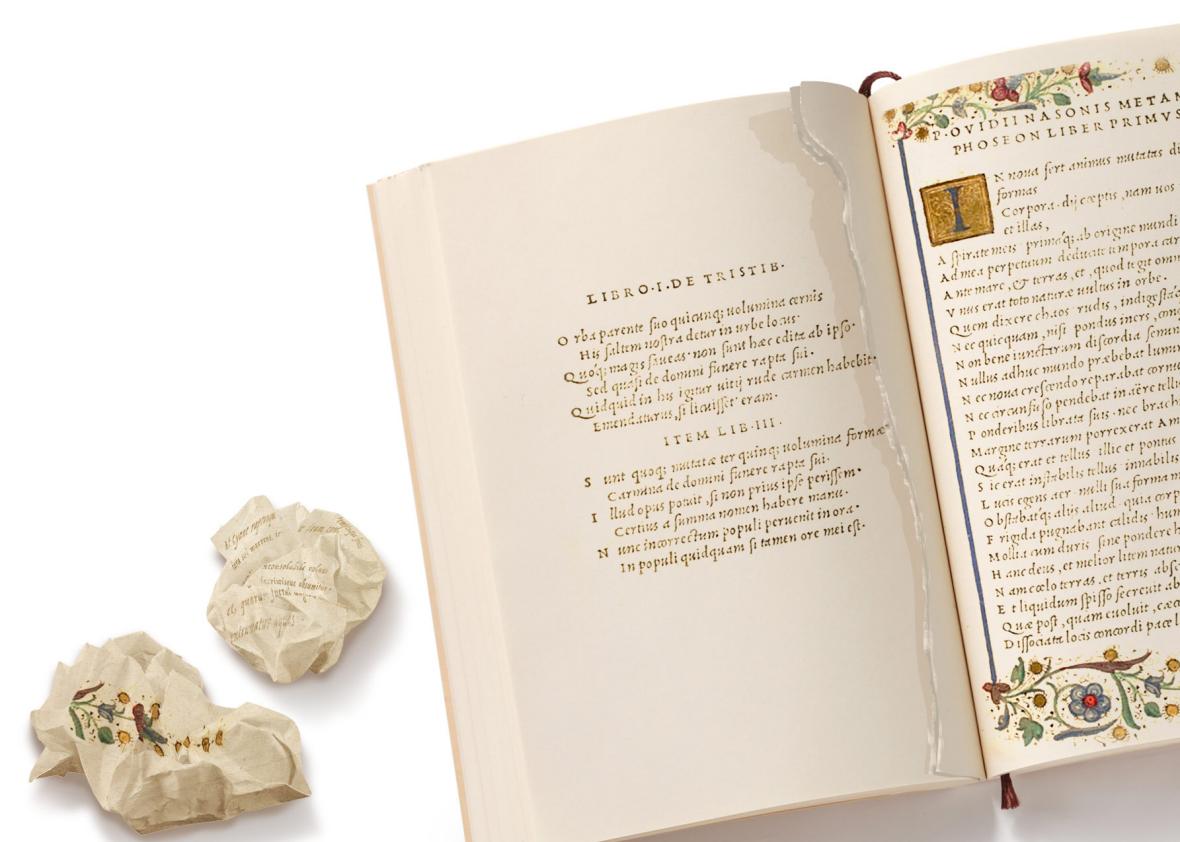

The Atlantic piece cited Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart and F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby as two classic texts that have stirred calls for trigger warnings due to their racially motivated violence and domestic abuse, respectively. Students at Rutgers in 2014 beseeched a professor to append a trigger warning to descriptions of suicidal thinking in Mrs. Dalloway; students at Columbia did the same in 2015 for scenes of sexual assault in Ovid’s Metamorphoses. In some cases, the flags are meant to shepherd students away from high-voltage material; in others, they simply advise readers to be prepared. Often derided or ironized online by concerned citizens (and especially by free speech advocates), they are a response to something real: Scientists agree that triggers can awaken dormant memories and hijack the rational control board of the cortex, drowning awareness of the present moment in eddies of panic.

As Ali Vingiano recounts for BuzzFeed, trigger warnings were born not in the ivory tower but on the lady-blogosphere, where they prefaced message-board postings about topics like self-harm, eating disorders, and sexual assault. The advisory labels swam to LiveJournal in the early aughts, then spread across Tumblr, Twitter, and Facebook. By 2012, they speckled such feminist sites as Bitch, Shakesville, and xoJane, creating protective force fields around articles that touched on everything from depression to aggressive dogs. These internet “heads up” notes allowed vulnerable readers to tread lightly through and around subjects that reignited their pain. But they also acquired a sanctimonious, performative aura. “As practiced in the real world,” Amanda Marcotte wrote in Slate last year, “the trigger warning is less about preventive mental health care and more about social signaling of liberal credentials.”

Similarly, the vaudeville toughness of Ellison’s letter felt designed more to make a cultural point than to edify students. Enacted correctly, the measures Ellison invokes are not supposed to constrict academic horizons. They are meant to secure for minority students the same freedoms to speak and explore that white male students have enjoyed for decades.

A spokesman for the University of Chicago, Jeremy Manier, acknowledged on the phone that at issue were “intellectual safe spaces,” not safe spaces in general: The university has already thrown its support behind a “safe space program” for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender students. Individual University of Chicago professors, Manier added, are also welcome to use trigger warnings if they so choose.

For all the furor they inspire, trigger warnings are relatively rare. According to a National Coalition Against Censorship survey last year of more than 800 educators, fewer than 1 percent of institutions have adopted a policy on trigger warnings; 15 percent of respondents reported students requesting them in their courses; and only 7.5 percent reported students initiating efforts to require trigger warnings.

Photo illustration by Natalie Matthews-Ramo. Photos by Thinkstock.

What’s more, as the survey notes, while media narratives paint these cautions as forms of left-wing political correctness, a significant minority of trigger warnings arise on conservative campuses in response to explicit or queer content. NCAC executive director Joan Bertin told me that the survey yielded more than 94 reports of sex-related trigger warnings, including from art history teachers displaying homoerotic images and studio drawing teachers importuned to announce nudity and help “conservative students … feel more in control of the material.” A professor wrote in that he’d offered a trigger warning after “a Rastafarian student was very offended at my comparison of Akhenaten’s Great Hymn to Psalm 104.” Requests for advisory labels stemmed from representations of famine, gender stereotypes, childbirth, religious intolerance, spiders, and “sad people.”

Given the myths and emotions enveloping the issue of trigger warnings and safe spaces, it’s worth asking what science can tell us about the actual effects of verbal triggers on the body, brain, and psyche. Certain people experience certain words as dangerous. Should they have to listen to those words anyway?

* * *

During the winter of her freshman year in college, Lindsey met a guy, a junior, at a party. A week later, he asked her to another party and picked her up in his car. She didn’t realize something was wrong until he pulled into a parking lot and told her to get in the backseat. When she refused and asked to go home, he informed her that they weren’t going anywhere until she had sex with him. Then he climbed on top of her and raped her.

It took years for Lindsey to find her way to a therapist, where she discovered that the occasional flashbacks, phantom sensations of being touched, and breathlessness she experienced in the wake of this violation were symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder. The episodes struck whenever she saw or read words associated with sexual violence: rape, molest, attack, even incest. She’d notice a tingling shock in her chest and “the feeling of fear, maybe a flash of a point of time during my assault, and sometimes it was like he was doing it again,” she says.

Several months ago, a friend of Lindsey’s was regaling her with stories about the movie Room, in which the young female protagonist is imprisoned for years in a shed and repeatedly raped. Lindsey hadn’t seen it, didn’t want to see it; yet when her friend said the word trapped, she detected the unwanted caress of her disorder across her body, felt her pulse begin to race.

But Lindsey was careful to conceal her agitation from her friend. “I’m pretty good at keeping my cool,” she says now. They moved on to a different topic.

Lindsey’s friend didn’t realize it, but her descriptions of the movie were acting as triggers, opening a trapdoor in Lindsey’s memory. In psychological parlance, a trigger can be any stimulus that transports a PTSD sufferer back to the original scene of her trauma. It might be visual (a red baseball cap like the one an old abuser wore, a gait or facial expression) or aural (a whistle or slamming door). Some people are triggered by the smell of cigarette smoke or traces of a specific perfume. Others react to spoken or written language: words that switch on the brain’s stress circuits, bathing synapses in adrenaline and elevating heart rate and blood pressure.

Activated by signals from the language-processing bureaus of the brain, the amygdala—the neural fear center—blazes to life. Your palms may sweat, your ears ring, your mind buzz with the jagged fragments of a horrendous memory. “It’s not an experience you’d wish on an unprepared young person,” says Debra Kaysen, director of the Trauma Recovery Innovations Program at the University of Washington.

Trigger warnings extend the option of avoidance (in some cases), but state-of-the-art PTSD treatments depend on confrontation, albeit in strictly titrated sessions. While it seems counterintuitive to linger over words and phrases that cause you sorrow, examining your feelings in the aftermath of a harrowing ordeal can be essential to healing. Edna B. Foa, professor of clinical psychology at the University of Pennsylvania, has done more than anyone to propagate this idea; she developed prolonged exposure therapy, or PET, a highly effective PTSD treatment that stresses engaging with your triggers—slowly, methodically—until they lose their power.

“If people go through a trauma and do not recover, they are suffering, they are dysfunctional, and the way we know how to reduce symptoms and improve their quality of life is to talk about the event, to process it,” Foa tells me. “If people are saying, ‘I don’t want to think about the event because it upsets me,’ that’s probably the reason they didn’t get better.”

The practice of PET is twofold: With “imaginal exposure,” patients revisit the traumatic memory by narrating it aloud, over and over, almost to the point of boredom or senselessness. In “in vivo exposure,” they re-enact situations in real life that remind them of their trauma, staring down situations and objects that may cause distress but are not in fact dangerous. In vivo exposure aims to unravel associations between the loud noise and the wounding moment, to disentangle trigger from symptom.

It’s in vivo exposure that may have a role to play in a junior seminar on the 19th-century colonial novel. When a patient presents with triggers that take the form of words, Foa says, she encourages him not to skirt contexts in which those words might materialize. Drive to the local veterans center, awash in the stories of fellow soldiers, and ask people questions about their military service; read the paper; watch the news. She has instructed patients who’ve experienced sexual violence to search for accounts of rape online, so that they can sift through their reactions in their next therapy session. Do it with a sister or a partner, she urges. Or do it by yourself. You’re strong enough.

In a metaphor with particular resonance for the debate around trigger warnings, Foa compared trauma to sentences inscribed on the pages of memory. A flashback opens the memory book to a specific chapter and forces you to read. You slam the covers shut, but doing so requires tremendous effort. Then another flashback transports you to a different chapter, until you can wrestle the volume closed again. The purpose of PET, Foa explains, is to help you read the book from beginning to end. Only after you’ve walked the entire length of the narrative, seen the plot unfold its horrors in legible order, are you able to put it aside. When you decide to open the text, rather than waiting for a trigger to do it, you take control.

What does this mean for the physical books of the classroom? In their Atlantic story, Greg Lukianoff and Jonathan Haidt argue that enlisting trigger warnings as bodyguards against your personal demons runs counter to the spirit of PET—that students should “read” from beginning to end. They believe academia is an ideal place in which to process rekindled feelings and memories. In a seminar, they write, “a discussion of violence is unlikely to be followed by actual violence, so it is a good way to help students change the associations that are causing them discomfort.”

But Foa doubted that classroom settings could provide the delicate therapeutic command needed to tame a patient’s trauma. When a trigger arrives, “there will be arousal; the person may be overwhelmed,” she says. If a doctor isn’t present to keep disturbance within bounds, or if the patient isn’t alone or with a trusted friend, she may have trouble coping with the flood of alarming memory.

Even without a trauma expert disputing PET’s hypothetical efficacy in the classroom, getting help seems like a decision you make with a psychiatric professional, not a professor. No student should feel compelled to relive her worst experiences before an audience of her peers, for course credit. PTSD treatment wants to neutralize triggers, defusing their necromancy and transforming them back into words. But the literature courses that tend to provoke calls for trigger warnings are designed to unleash the potency of language. These are different, even opposing, goals; success by one metric has little to do with success by the other.

That said, Foa isn’t convinced that those with PTSD would suffer flashbacks “reading accounts of what happened” to fictional characters. A “therapeutic distance” exists, she says, between confronting your past and imagining someone else’s. Even though graphic stories retain the power to disturb, Foa says, “I do not appreciate this idea that people should always decide whether or not they will be made upset. If we act as though they cannot handle distressing ideas, we communicate the unhelpful message that they are not strong.”

Foa’s comment illumines a vast gray area in the trigger warning debate. In the fervor around awareness and empowerment, are university activists using the term trauma too loosely? “I question whether hearing words that have a certain connotation because of our culture or historical context really counts as a trauma,” Kaysen says. “They may be really upsetting, but I don’t know that there’s data to suggest that they would cause PTSD symptoms.”

* * *

A slim but intriguing set of clues prompts the question of whether microaggressions—the thousand daily paper cuts of being black in a racist world or gay in a homophobic one—can give you PTSD. As Kaysen explains, men and women who’ve weathered systematic oppression, particularly due to their group identity, are at a higher risk of developing other mental health issues such as anxiety and depression. PTSD or no, the black kid who is expected to address the appointed faculty head of his dormitory as “master” (which was until relatively recently the case at Harvard, Princeton, and Yale) remains more psychologically vulnerable than his white classmate.

Photo illustration by Natalie Matthews-Ramo. Photos by Thinkstock.

So what about him? And what about the majority of us, saddled not with a diagnosable condition like PTSD but with an idiosyncratic set of sensitivities and weak spots? What about the Latina student achingly attuned to racial slurs or the depressed student perversely beguiled by the vocabulary of self-harm? Given all these competing concerns, how do we decide how to use language in the classroom, and in the world?

Whether we do or don’t have PTSD, words still find ways to operate on our emotions. In 2011, researchers at the University of Bristol found that people react automatically and intensely to profanity in ways that they don’t to euphemisms. The experimenters argued that “the heightened response to swear words reflected a form of verbal conditioning in which the phonological form of the word was directly associated with an affective response.” In other words, the very sound of the swears was like a rubber hammer to the knee, circumventing the conscious mind to trip the autonomic system.

A suite of studies reveals that specific phrases—“telling the other person what to do, delivering ultimatums, labeling the other person, and characterizing the other person’s motives”—evoke measurably stronger emotions in people and “often lead to communication breakdowns.” In these cases, a neural area called the ventral anterior cingulate cortex “seemed to be sensitive to conflict when stimuli were emotional. … [The ventral ACC] is also strongly connected to the amygdala, a structure in the temporal lobe that rapidly responds to emotion in stimuli … and is activated when emotional words are presented.”

“Emotional words”: The category is a large one, including specific topics, insinuating metaphors, and vivid figures of speech. Several weeks ago I was handed the script for an advertisement I was supposed to read on a podcast. The ad described a program that collates thousands of magazine articles, making them readily available in one place. “Thanks to Netflix,” the script ran, “we’re all binge-watching. Thanks to pizza, we’re all binge-eating.” And now, thanks to this advertiser, “we can binge-read, too.”

My palms started to sweat, my head felt feather-light on my neck, a sick wave of shame purled through me. No, we’re not all binge-eating, but I was. Emerging from a decade of anorexia, I was the rare listener for whom this hyperbole wasn’t hyperbole at all. My mind flashed to the bright-colored wrappers in a desk drawer, the empty snack bags I’d crammed angrily into the trash can in my bedroom. I felt humiliated; when I tried to thank the producer for the copy, my voice shook.

And then it passed. I got through the recording without incident. And aside from a low whisper of anxiety in my blood for the next few hours, I felt fine. I wondered afterward: Should I have done anything differently? Was I supposed to speak up for all the eating-disordered listeners in our podcast orbit? Or would drawing attention to the ad’s clumsy phrasing have been self-indulgent, not to mention professionally unwise? Isn’t stumbling over stimuli that cause you discomfort just part of being alive?

If I’m honest, the very term binge-watching bugs me. I don’t like hearing a word I associate with so much mental agita lassoed into a cute metaphor for media consumption. To use a hyperbolic phrase—one I’m suddenly aware might upset people who’ve brushed up against suicide—it makes me want to die. Yet binge-watching is catchy, indisputably useful. I wouldn’t dream of telling a friend or a television critic to please avoid it on account of my gossamer feelings. Maybe that’s the difference between having PTSD and being any average human being with a personal kit of needling memories and experiences. Outwitting your terrorized amygdala so that you can live your life with a semblance of peace is one thing; begging the universe to conform to the shape of your bespoke sensitivities is another.

People make these calculations daily. “My dad died a couple years ago from a heart attack, and I’m now hyperaware of how often people use metaphors involving heart attacks to evoke shock,” Jasper W., a 28-year-old management consultant in New York, tells me. Jasper tries not to “make a fuss” when he hears the cliché, “in part because talking about your dead parent is always awkward, and also because I can otherwise be a stickler about correcting people’s insensitive language,” he says. Jasper experiences the heart attack trigger as “a little pang of anxiety that I quickly bury,” concluding that he has “bigger fish to fry.”

Annalisa, a 22-year-old graphic designer in New York City, often performs a similar math. “I lost my mom a year and a half ago to leukemia,” she writes me. “The phrase cancer survivor—as if those who died of cancer are losers—triggers a lot of anger.” When I asked her over Slack how she deals with hearing the term, she says, “I usually let it go because addressing it will probably be emotionally hard. … I just rant about it later with someone else.” Then she messaged me the “slightly smiling face” emoji, which poignantly contained the currents she’d alluded to: an attempt to grin through pain, imperfectly achieved Zen, hesitance seeping through the cracks of a glossy cartoon. As much as young people today court censure for seeming to embrace “victimization,” most of the planet still faces tremendous pressure to be OK.

This is a theme worth spotlighting—that for all the supposed grievancemongering of modern identity politics, everyday life tends to demand that we suppress any unhappiness and put on a cheery face. Anecdotally, far fewer people bludgeon their acquaintances for using callous language than quietly force their discomfort underground. “I don’t want to insult anyone,” I heard over and over when I asked folks about their reactions to personal triggers. “I don’t want to be rude.”

Photo illustration by Natalie Matthews-Ramo. Photos by Thinkstock.

There are those who speak up. Recently, I wrote a blog post in which I referred to the “epileptic throb” of a synthy, New Age soundtrack; a reader emailed about my thoughtless word choice, imploring me to consider “the many people who have epilepsy, and who read Slate.” I didn’t know how to react. I had been proud of that adjective-noun combination platter. I didn’t immediately understand why someone would take offense at the metaphorical invocation of a disease or misfortune: Don’t we call bigotry “a cancer” on a senator’s legacy or denounce a verdict as “a miscarriage of justice”? But I also felt guilty—my use of epileptic had been playful and descriptive, not solemn or morally charged. Perhaps I’d trivialized the disorder by yoking it to a piece of music; in any case, there were plenty of other ways to get my point across.

So what’s the solution? It can sometimes feel as though modern language codes pit expressive richness and variety against empathy and compassion. The binary’s imperfect, but pick your team. On one side of the ledger sits the world, which becomes a more vivid and beautiful place when we have vaster vocabularies to draw on, more plots and situations to behold; on the other side are human beings, who have an obligation not to hurt each other when they can avoid it.

The most innocuous form of trigger warning—the one that simply alerts readers that difficult material is coming and advises them to be on guard—seems compatible with a full, humanist embrace of what some philosophers might call the “lifeworld,” the coherent universe of things we might experience. Except maybe it’s not, not really. “I think trigger warnings are counterproductive to the educational process,” Bertin, the National Coalition Against Censorship director, states flatly. “By all means, tell students what you’ll be teaching in your course. But don’t tell them how they’re going to feel about it.”

Advocates for the labels herald them as trust-building exercises, practical notes that help students feel “seen.” Yet in presuming that a reader will take offense or crumble under the pressure of certain topics, do trigger warnings interpret text before we have a chance to draw our own conclusions?

When I reached out to the University of Chicago for comment on John Ellison’s welcome letter, its press office forwarded me a faculty report from the Committee on Freedom of Expression, a group convened by the school in 2015 to “draft a statement articulating the University’s overarching commitment to free, robust, and uninhibited debate and deliberation among all members of the University’s community.” It reads:

The University’s fundamental commitment is to the principle that debate or deliberation may not be suppressed because the ideas put forth are thought by some or even most members of the University community to be offensive, unwise, immoral, or wrong-headed. It is for the individual members of the University community, not for the University as an institution, to make those judgments for themselves, and to act on those judgments not be seeking to suppress speech, but by openly and vigorously contesting the ideas that they oppose.

This is, I think, the correct way to conceptualize the role of a university in developing its students’ mental framework. It also strikes me as almost entirely irrelevant. It channels a sentiment that few campus activists would dispute, and it sidesteps the issue of what to do with ideas that are not so much “wrong-headed” as psychologically painful or eroding. If the university as an institution chooses to grant a speaking platform to some luminary students disagree with—as Yale, Oberlin, and Wesleyan have done, notoriously, in recent years—then surely those students can protest in order to “openly and vigorously contest” both the ideas and the university’s tacit endorsement of them.

The notion that trigger warnings violate “freedom of expression” has a similar smokescreen quality. An earmark—even one that may end up steering particular students away from a text—is not an act of censorship. If trigger warnings perpetrate harm, they don’t do so by uprooting our democratic ideals. They do so by constricting our imaginations and, perhaps, by preventing us from facing our fears.

Researching this piece, I kept mulling over “Mirror,” the spectral Sylvia Plath poem in which a looking glass describes the habits of her nervous owner. “A woman bends over me/ searching my reaches for what she really is,” the mirror says. “In me an old woman/ rises toward her day after day, like a terrible fish.”

Foa compared traumatized memory to a book you can’t stop reading. I think about Plath’s mirror-that-is-a-lake. I think of a veil of placid waters smoothed over the worst one’s psyche has to offer. Occasionally dread or shame or sadness surfaces. Then it sinks back down. But those drowning currents and terrible fish are more than stray encumbrances—they are part of the person; they live in her looking glass. It’s transcendently unfair, and you can go around and around trying to wrestle with it, and those with and without PTSD will join you, mourning the ways in which life doles out heartbreak and flaws to mock the beautiful things we want.

This procession of grief should never be dismissed. In fact, it is the starting point for empathy. But my point is: Perhaps the anger at being triggered borrows some of its heat from a more elemental anger—why did this happen to me? Why do these weak spots, these sites of appalling tenderness, have to be a permanent part of my life? Given how fiercely I long to disown the personal history that animates my responses to particular words, I can only imagine how intense that desire might be for someone who has experienced true trauma. Yet I can’t help but hear in the rejection of trigger warnings Plath’s character “searching … for what she really is,” or at least for a piece of what she is. I can’t help believing that to avoid your triggers means to avoid yourself.

* * *

PET is the most famous, laurelled treatment for PTSD and other anxiety disorders, but it’s not the only one. Since the late 1980s, psychologists have also turned to acceptance and commitment therapy, or ACT. Developed by Steven C. Hayes during that decade’s flowering of cognitive behavioral methods, ACT resembles its older cousin, PET, but at a slight angle.

Where Foa’s signature tactics focus on defanging triggers through repetition, ACT is concerned with the “cognitive inflexibility” that is characteristic of people with keen anxiety. These patients often suffer from “thought-action fusion,” or the belief that their thoughts carry an eerie efficacy or truth.

In the fuser’s distorted worldview, you may imagine your family dying in a plane crash and conclude you are an evil person, or even that you have tugged destiny’s robe. Or perhaps you criticize yourself as an eternal loser and grow convinced, in thinking it, that you have made it so. (Consider, as another version of this, the deathless relationship-squabble refrain: Just because you think that doesn’t mean it’s true!)

ACT works by challenging the domineering force of these unbidden, intrusive thoughts. Patients are encouraged to cultivate a sense of the “self-as-context”—of a separate, curious, and empathic you who observes each inner experience as it drifts by. The therapy “helps create a certain psychological detachment from your thoughts, so that you can sit with them,” says Darby Saxbe, an assistant professor of psychology at the University of Southern California and a sometime Slate contributor. According to Hayes’ model, no piece of mental flotsam “is deterministic, no memory so distressing or dangerous that you can’t build tolerance and acceptance and move forward,” Saxbe says.

For people with verbal triggers, the goal of ACT is to upend the internalized belief that any bit of text can wield damaging, identity-unraveling power. You are not your thoughts; you can rise above your memories. If the governing metaphor of PET remains the memory book of trauma, ACT’s central figure is a stream carrying along a peaceful cargo of fallen leaves. When you have an upsetting thought or feeling, the treatment’s exercises instruct, imagine it as just another leaf floating down the river. Notice it, observe it, and let it go.

“Cognitive avoidance is really counterproductive,” Saxbe says. “It can have rebound effects, such as more flashbacks, because the memories aren’t fully processed.” ACT thus shares PET’s emphasis on exposure, though it subtly reframes that approach’s priorities. When I spoke to Foa, she underlined the importance of reducing traumatic reactions, the kind of stress responses that Lindsey dealt with when her friend said the word trapped. Though ACT also has the salutary effect of curtailing flashbacks, its practitioners are more interested in transcending PTSD symptoms when they strike. This goal—allowing patients to live the lives they want, despite bursts of unpleasantness—is conceptualized as “moving in a valued direction,” Saxbe says. It means identifying what’s important to you, deciding what you want to do, experiencing all the anxiety and pain and awfulness that the human brain in collaboration with the gods deposits in your lap because you are alive on Earth, and doing it anyway.

As for trigger warnings, “they send the message that language itself is going to damage you, and that’s simply not true,” Saxbe says. “Narrative doesn’t have the power to control us. Even coping with anxiety, we can choose how to structure our lives.” When I point out that flashbacks are scary and uncomfortable, Saxbe counters with the gentlest and most empathetic “so what?” I’d ever heard. PTSD symptoms “won’t hurt you,” Saxbe says. “They won’t shatter the integrity of your body or your mind.”

ACT seems to offer students a new calculus for when to miss class and when to read on. If participating in your literature seminar aligns with your values, if it fulfills certain goals related to how you wish to arrange your life, then you might consider braving The Great Gatsby’s provocations. (And if your course schedule doesn’t reflect your values or goals, then maybe you picked the wrong major?) Seen as a form of in vivo exposure, and thus a component of PE therapy, a verbal trigger in a college setting is a lash of emotional incitement in an academic space. You might argue that its activations are best courted elsewhere. But if a verbal trigger and its ensuing response are just byproducts of “moving in a valued direction,” it doesn’t really matter where they “should” be. They’re there, on the seminar table, and if you want your actions to express your ideals and aims, you know what you need to do.

The encounter will likely cause discomfort. But as Saxbe might put it, so what?

* * *

When Jennifer, a D.C. woman now in her mid-20s, was a senior in college, she received word that her boyfriend, a soldier stationed in Virginia and about to deploy to Afghanistan, had attempted suicide by opening his wrists. Several weeks after a nightmare that involved recovering his bloodstained phone from his apartment, contacting his parents in Germany, and being refused entry to his hospital room, she acquired a PTSD diagnosis.

Speak to Jennifer about the military today, or mention “being deployed,” and her chest will tighten. A torrent of anxiety will sweep through her body, stealing her breath away and making thought impossible. She says that reading her favorite book, Slaughterhouse Five, now constitutes “torture.” If her friends or family start discussing the Army, she needs to walk outside.

Jennifer—that’s not her real name—is one of my close friends. I didn’t know about her ex’s suicide attempt, or her PTSD, until I told her I was writing this article. When I ask her how it felt to recollect and express what happened to her, she replies, “You have to be able to talk about it to be sane.” She can’t “bottle it up and let it destroy me.” As for trigger warnings, “I feel like maybe I have a harsher view on the world now, because of course I don’t want people to have to relive that pain,” she writes in a Facebook chat. “But I also want to say, ‘No, it’s fine. They deal with that misery all the time.’ ”

“All the time?” I press her. I could have added: Like when we were having drinks on your couch? When you did a stand-up routine at your own karaoke party?

The pain and sadness doesn’t ever really dissipate, Jennifer admitted. It ebbs and flows, like a river.

You think you know a person and you don’t. You think you’re telling your friend about a movie you liked, and you’re flooding her mind with ghosts.

But Jennifer, for whom certain words or phrases grow spines and teeth, did something unexpected with her triggers. One year after the events that gave her PTSD, she opened a Google document and wrote it all down. She wrote “through tears,” she says, and “everything is spelled wrong.” Yet in using the very language that harrowed her to give shape to her experience, she found some relief.

You can’t defeat trauma by avoiding it. Pushing it away only makes it more supple. Jennifer named her Google document “I can’t leave you alone,” and I had to pause when I saw the title, because I’d thought it was the other way around. We long for the past to let us be, but the reality is more complicated. We need to learn how to let the past be.

Is that what writing—carefully re-enacting your story in language—teaches you? With every sentence we set down, we leave behind a feeling, a memory. It would explain why so many people with difficult histories turn to memoir—not to testify, but to escape. “I thought if I could get it on paper and out of my head, it would be like moving on,” Jennifer tells me. Words, which open trapdoors and produce nemeses from the past, have an uncanny power to hurt us. But they can also be our salvation.