What Happens When a Disruptor Gets Disrupted

The war between auto dealers and TrueCar, a company that wanted to change car sales.

Photo illustration by Lisa Larson-Walker. Photos by Getty Images, Thinkstock.

This article originally appeared in Inc.

A few years ago, Scott Painter had it made. He was wealthy, handsome, and smart, a TED and Davos guy who hung out with Elon Musk and Richard Branson. “Everything in my life had gone unbelievably well,” he says. “Just off-the-chart success.” Over two decades, he had started dozens of companies and raised more than $1 billion in venture funding before finally hitting upon his Really Big Idea in 2005: A company eventually called TrueCar would bring price transparency to the sneaky world of auto salesmanship and give consumers leverage by telling them exactly how much other people were paying for cars.

For car shoppers, it was nirvana: no more haggling, no more waiting for that gold-chained salesman to talk to his manager to “see what I kin do.” Instead, you just went to TrueCar.com, typed in your ZIP code and the make, model, and extras you wanted (don’t forget the fuzzy dice!), and printed out a voucher, redeemable at your local TrueCar dealer, with a guaranteed low price. It was free and easy. And dealers paid TrueCar only if the lead turned into a sale—$299 for new cars, $399 for used.

Dealers signed up by the thousands, hoping to make up for lost ground after getting whacked by the Great Recession. Customers loved it, flocking to TrueCar’s site and those of Capital One, USAA, and other partners that used its technology for their car-buying programs. Investors were thrilled too, ponying up more than $185 million in venture capital. With Painter as chief executive, TrueCar reached nearly $76 million in sales by 2011, went public this past May, and, in its first quarterly earnings report, beat analyst expectations for revenue ($50.5 million) and Web traffic (4.2 million unique visitors per month). In September, its certified dealer count hit 9,000.

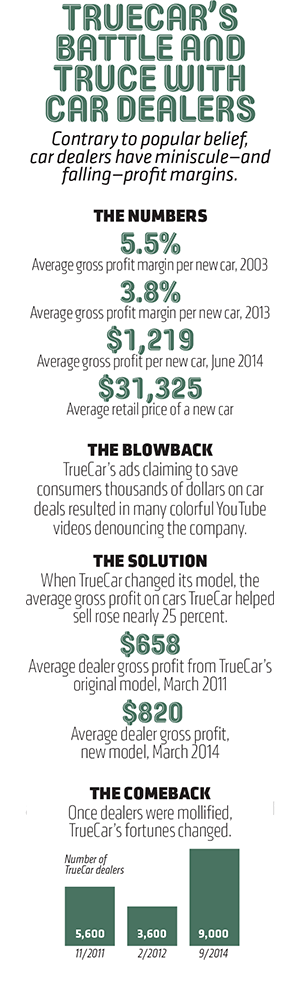

But in early 2012, TrueCar nearly became just another overhyped Internet flop. The problems started just as it was gaining critical mass, airing national TV spots showing real customers saving $3,000, $8,000, even $14,000 on their cars. What those ads failed to mention is that most dealers, despite their greedy reputation, make very little money selling new cars. The average profit margin of a new-car sale was only 3.8 percent last year, according to the National Automobile Dealers Association; most dealers survive on ancillary services such as maintenance, financing, and warranties. “If I pay TrueCar $299 for a lead, I just gave away much of the gross profit on that car,” says Donald Hall, head of the Virginia Automobile Dealers Association, who tangled fiercely with Painter.

Near-hysteria broke out among dealers, who feared that TrueCar was encouraging a destructive race to the bottom that would disrupt them right out of existence. In a speech in 2011, Mike Jackson, CEO of AutoNation, the nation’s largest auto retailer, called the situation “a death spiral” for dealers.

The blogosphere lit up. Dealers began telling Painter exactly where he could put those vouchers. Big dealer chains cut ties with TrueCar. State associations told members they could get in trouble with regulators because Painter’s company was possibly violating state franchise laws designed to protect dealers. Honda threatened to cut off advertising funds to TrueCar dealers who sold vehicles too cheaply, arguing that it would harm the brand’s image. Pictures of Painter as the devil circulated on the Internet. “Basically, they suck!” screamed an auto sales trainer named Jerry Thibeau in a typical YouTube video.

Between December 2011 and February 2012, a third of TrueCar’s 5,600 certified dealers canceled. Without dealers, it had no business. At TrueCar’s offices, in Santa Monica, California, they had a nickname for the crisis: the Swirl. By that, they meant maelstrom, though it also conjured images of TrueCar spinning down the toilet. Before the Swirl, TrueCar had $40 million in cash and was growing rapidly by every measure, from dealerships and cars sold to revenue and Web traffic. But all the dealer defections caused TrueCar to lose $75 million in 2012, and its TV ads disappeared. “I thought, ‘Holy shit—in 45 to 60 days, I’m out of business,’ ” Painter says.

Painter’s personal life also began to crumble. He was fighting a bitter custody battle with his ex-wife over his two oldest children, and his second marriage was falling apart, he says, because he was so focused on trying to stop the Swirl that he neglected his wife, who was trying to deal with two young children and an unavailable husband. “I was a horrible husband and a horrible father,” he says. Panic attacks left him unable to breathe. So he went to the doctor—and was told he had a serious congenital heart defect and had to lose 50 pounds and stop drinking immediately.

The failure of TrueCar would also mean personal financial ruin because Painter had invested so much of his own wealth in the company. As his performance bonuses dried up, he fell into debt and had to beg his board of directors for a pay raise to support a lifestyle that included a house in Bel Air, a nine-car garage, and a $220,000 silver Aston Martin Rapide.

In early 2012, a desperate Painter did what any upscale 43-year-old Californian whose life was imploding would do: He turned to his therapist. “What’s going on?” he wanted to know. “Why is all this happening to me?”

His therapist thought for a moment and said, “Have you ever thought that all of this is your fault?”

Painter fell silent. That had never occurred to him. To the words he uses to describe himself—workaholic, idealist, perfectionist—nobody who knows Painter well would argue with adding charming, intelligent, creative, hyperarticulate, and deeply committed to his techno-libertarian beliefs. But, as shocked as Painter was, the therapist had a point. Today, Painter himself says, “I’m an arrogant jerk.” And sometimes, he adds, “a complete asshole!”

Arrogant jerkdom takes years to develop, as any shrink will tell you, and for Painter it began in middle-class Sacramento, where he grew up with a stepfather who was “a real hard-ass.” Painter was a restless, precocious lad. Inspired by his grandfather Ed Swofford, then CEO of Aloha Airlines, he started his first company, an automobile-detailing service, at age 14. Later, he joined the Army, studied at West Point (political science and engineering), and went to the University of California at Berkeley (economics) on a rugby scholarship. He graduated from neither school. A Berkeley class project led to InfoAccess, his first company to offer car-buying information online to consumers.

Since then, Painter has founded a staggering 36 stock-issuing, incorporated companies. “I love manifesting things out of thin air,” he says by way of explanation, adding that he probably has attention deficit disorder. He also loves cars, which you might guess from the nature of many of his startups. Prior to TrueCar, he was probably best known for CarsDirect, which he launched in 1998, raising $350 million in venture capital. Painter resigned as CEO the following year under pressure from investors after he laid off 90 people. As its name implied, CarsDirect aimed to sell cars directly to consumers from the manufacturer, leaving out the middleman. So it’s easy to see why many auto dealers still despise Painter—despite the fact that they share certain traits, including a love of choice expletives. “When people say, ‘Scott’s evil!’ they go back to CarsDirect,” says Painter. “How can you be a dealer and hear that and not go, ‘I hate that fucking guy!’?”

What Painter learned from CarsDirect, and a failed car venture he tried called Build-to-Order, is that the auto franchise system is so protected by state laws, and so politically powerful, that it’s nearly impossible to defeat it in any battle. (As his buddy Elon Musk has discovered while trying to set up Tesla dealerships.) So with his next company, Painter decided to partner with dealers. All he had to do was convince them that the information revolution was rendering their old-school selling methods obsolete. If consumers can buy a computer or dishwasher for nearly the same price at a variety of retailers nationwide, he argued, why should the price of a car vary up to 45 percent from one dealer to the next? “We believe that buying a car should be fun and should be fair,” Painter declared. “Cars are one of the last commodities that don’t behave like commodities because of the franchise system.”

Talk of the digital revolution was not exactly embraced by car dealers—price transparency being digerati-speak for “lower prices”—but many felt they had little choice. In 2005, Painter and his associates founded Zag.com to run the car-buying programs for big corporations and member-based organizations such as AARP. (Today these businesses account for more than half of TrueCar’s revenue; 38 percent comes from ordinary consumers visiting TrueCar.com and related mobile apps, and the rest comes from selling data and consulting to auto and finance companies.) Three years later, Zag launched TrueCar, which culled pricing information from a multitude of sources—finance and insurance companies, vehicle registration, dealers, and other data aggregators—to give consumers something they had never seen before: an up-to-date, real-life snapshot of what people actually pay for cars. In 2010, the two companies merged under the name TrueCar.

Painter’s pitch resonated with investors partly because they could all relate to how miserable it can be to visit a car dealership. According to a recent survey by Edmunds.com, one in five people said they’d willingly give up sex for a month rather than haggle for a new car. One in three said they’d rather do taxes, go to the DMV, or sit in an airplane’s middle seat. It became Painter’s mission in life to fix that. After his first two kids were born, he decided that TrueCar was his perfect chance to settle down and finally build a sustainable company.

Some dealers loved the leads TrueCar provided, especially when car sales dropped off a cliff during the financial crisis of 2008. “TrueCar is better than other lead generators, because customers get a price they can believe and I don’t have to pay unless I make a sale,” says John Harmond, general sales manager of Santa Monica Ford/Lincoln-Subaru, who has used TrueCar since its earliest days. Though Harmond has to pay $299 for every sale, TrueCar argues that dealers like him can actually save more than $1,000 per transaction, through reduced haggling time and inventory costs as cars sell faster, and by cutting back on marketing and sales staff. About 5 to 6 percent of TrueCar leads turn into sales, Harmond says, far better than the 2 to 3 percent from other lead generators, such as Edmunds.com.

Still, Painter admits that his company was so consumer-centric and had whipped itself into such a frenzy with what he calls its “Stick it to the man!” attitude, that dealers felt under attack. One TrueCar employee got so carried away that he registered the domain name fuckedbythedealer.com. Painter says he would never authorize such a thing and was shocked when he found out, and the employee was promptly fired. But by that time, the damage had been done.

And, as for that “complete asshole” thing—well, one moment that stands out came when Painter sat down for a family Thanksgiving dinner in 2011. At the table was his brother-in-law, Phil Kerr, a Mazda dealer in Arizona. With TrueCar at its pre-Swirl peak and its flashy ads saturating TVs nationwide, Painter began gleefully berating Kerr about how dealers like him would get steamrolled by the digital revolution unless they embraced Internet-driven price transparency—all while the rest of the family was attempting to enjoy their mashed potatoes and drumsticks. “I was such an arrogant ass to put him in his place,” Painter says.

What Painter didn’t know was that the tide had already begun to turn, and within mere weeks, the Swirl would begin to overwhelm TrueCar. Those TV ads played a big role—dealers saw that $3,000 to $14,000 in consumer savings coming directly out of their pockets—and industry bloggers began hammering TrueCar. “Your company is evil,” wrote Jim Ziegler, an industry consultant and a leader of the dealer revolt. “Your agenda is to destroy us.”

TrueCar was also accused of violating state laws by acting as a broker and extracting too much valuable customer data from dealers’ computer systems. Painter denies that TrueCar was ever a broker, but the company voluntarily suspended service in Louisiana and Colorado while it overhauled its business model. Now it charges dealers a monthly subscription fee in some states, rather than on a per-deal basis, and operates legally in all 50 states and Washington, D.C. Troy Foster, TrueCar’s chief legal and compliance officer, insists that TrueCar is very clear with its dealers about what data it collects and how it is used and that it has never resold customer information to third parties. (Meanwhile, dealers and trade associations confirm they’ve received queries from the Federal Trade Commission about whether they violated competition laws by conspiring to boycott TrueCar; the FTC declines to comment.)

Struggling to reverse the slide, Painter hired Mike Timmons, a former AutoNation executive, to reach out to dealers. But this was as much a culture clash as a business dispute, with the colorful, rough-edged world of car dealers deeply distrustful of Painter’s elite team of technocrats from Santa Monica. One day at a dealer convention, Timmons approached Ziegler, who often wears a baseball hat emblazoned with his nickname, Alpha Dawg, and posts goofy videos of his attempts at rapping on YouTube. Timmons introduced himself and extended his hand in greeting—and Ziegler retorted, “I know who you are,” slapped his hand away, and kept walking.

Back in therapy, Painter realized that the solution to this mess was staring back at him in the mirror each morning. “Why don’t you start with the thing you can affect the most?” his therapist said. “Why don’t you go back and tell your wife, whom you love, that you’re sorry that you didn’t have the empathy to understand that she needed you to be there for her? And that it’s all your fault? Why don’t you own that and see how that goes?”

Painter did, going into couples therapy with his wife and saying almost those exact words. “Unbelievable!” he recalls. “The clouds parted.” His relationship with his wife improved immediately; now he had his first point of refuge in the storm. Next, he decided to try the same approach at work and found miraculous results there, too. “It became very easy to come into work and say, ‘You know, it’s actually my fault!’ ” he reports in a surprisingly cheery tone. “It became an almost intoxicating, gratifying thing to just own it.”

So he kept at it. Realizing he had not truly paid attention to the concerns of dealers—the lifeblood of his business—he went on a nationwide listening tour, meeting with dealer groups, car manufacturers, and industry media and influencers. “I realized very quickly it didn’t matter what I said. As long as I just took the blame for everything, we could get to a better place,” he says. “Almost all of these events were like AA meetings: ‘My name is Scott Painter, and I have violated all of you, and I want to change.’ ”

Next, Painter created a council of auto dealers that meets six times a year to tell TrueCar what it’s screwing up and what it’s doing right. He hired trusted insiders such as Pat Watson of the South Carolina Automobile Dealers Association and John Krafcik, former CEO of Hyundai Motor America. He spent 10 hours traveling to and from Norcross, Georgia, just to meet with Ziegler for a few hours to explain TrueCar’s new business model and show him the latest TV ads. They met at an outpost of the Cajun chain Pappadeaux Seafood Kitchen. “I was smirking at the very fact that I had this sprout-eating, preppy-ass Californian sitting in a Cajun restaurant eating spicy deep-fried alligator tails,” Ziegler boasted on his blog later. “I even took a photo of Scott Painter wearing my Alpha Dawg hat.”

Meanwhile, TrueCar.com scrapped its old slogan—”Know the Real Price”—and replaced it with “Never Overpay.” It has stopped showing estimates of how much dealers pay for cars. It no longer encourages dealers to beat the lowest price, instead rating dealer prices as good, average, or above average. The site also gives customers reasons to choose a dealer beyond price, including location and such added services as oil changes, car washes, and delivery. New TV ads talk glowingly about dealers as TrueCar’s “trusted partners.”

Painter also reformed his company’s culture. To drive home the point that TrueCar needed to do a better job balancing the needs of customers and dealers, he created a large metal seesaw etched with the word consumer on one end and dealer on the other. At company gatherings, groups of employees stood on both ends of the seesaw and tried to achieve a perfect balance.

While the new TrueCar has probably resulted in some consumers paying more for cars than they did using the old site, Painter believes he finally has a sustainable business model that benefits both buyers and sellers. He points to a recent TrueCar survey showing that most consumers believe dealers make a 20 percent profit on a new car—more than five times the average margin of 3.8 percent—and that if they discovered that dealers made nothing on a car sale, they would voluntarily tip them 8 percent. This shows that car buyers want the dealer to succeed, Painter says—they just don’t want to get ripped off. That’s where TrueCar comes in.

All together these changes produced a stunning turnaround. Since the depths of the Swirl in February 2012, TrueCar has more than doubled the number of participating dealers, to around 9,000, website traffic and the volume of cars sold have nearly tripled, and quarterly revenue has more than tripled.

Photo by Andrew Burton/Getty Images

Not all of TrueCar’s indicators are positive. Its IPO last spring, during a period of market volatility, raised only $70 million—its shares traded below its initial forecasted price—and its first earnings report this August included a $15 million net loss thanks to increased operating expenses, mostly for sales and marketing to attract new customers.

And Painter still has many critics. David Ruggles, a former dealer who is now a prominent consultant and writer, says, “I’m not mollified in the least.” He argues that TrueCar encourages the consumer to behave like a poker player who demands to see everyone’s cards before placing a bet. “Painter gets up and apologizes and says, ‘We were arrogant and we were wrong,’ because he lost millions in the dealer revolt. But his objective is still the same. The whole principle of demonizing dealers is opportunistic and I hate it. He’s not out to change the world for the better unless Scott Painter makes a buck doing it.”

TrueCar also recently annoyed dealers by announcing it will no longer offer financial credit to dealers who can prove a sale involved a third-party site other than TrueCar. Meanwhile, the mega retailer AutoNation plans to spend $50 million building its own Web tools to generate leads, cutting out Internet sites such as TrueCar and Cars.com. Some dealers are even turning the tables on Painter by showing customers TrueCar’s prices to prove how competitive their own offers are, helping them close the deal without paying a fee to TrueCar.

As for whether Painter has truly changed, others share Ruggles’ skepticism. “He’s still arrogant and full of himself,” says Hall of the Virginia state dealer’s association, who adds that he was using a “keep your friends close and your enemies closer” strategy when asking Painter to speak to his group’s annual convention in 2012. “But I like Scott and admire him, because he’s smart enough to recognize problems and change the way he operates. He walked into a lion’s den when he came to speak to us. It took a lot of nerve to do that.”

Painter is, at least, a wiser man about the forces of technological disruption, insisting that Internet entrepreneurs cannot have the same haughty attitude they did during the heady days of the ’90s. That’s when his CarsDirect was one of the many Internet companies to emerge from Bill Gross’ legendary Idealab, along with spectacular flameouts such as eToys. “Everybody was rolling with the zeitgeist of the time, saying the Internet is going to transform everything,” Painter says. “But that’s one of the blind spots of technology investing in general. Disruption for disruption’s sake is not a good idea in terms of creating long-term sustainable value.”

It took a lot of personal and professional turmoil for Painter to realize that. But today, he spends more time with his wife and children; he’s also lost weight and downsized his lifestyle by selling some of his cars. Now the company that he has bet all his chips on needs only another few thousand franchise dealers to reach the sweet spot of 11,000 to 12,000 that Painter believes will allow TrueCar to really take off—giving its certified dealers a competitive edge over the other 19,000 or so dealers nationwide while ensuring that TrueCar customers can choose from a wide selection of dealerships selling every major brand in all geographical regions of the country. That would put this restless entrepreneur on the path to creating a company he could someday leave for his children.

“The true spirit of disruption is to effect a better outcome,” says Painter. “Only by having this near-death experience did we realize that the real disruption would be to restore the trust between auto retailing and the consumer. The industry has a big existential crisis ahead of it—the consumer fundamentally doesn’t trust auto retail at all. Today, the consumer knows more about the car than the person selling it, and car dealers have worse reputations than members of Congress ... ”

Uh-oh. There he goes again.

See also: Seven Truths About LinkedIn