Americans Have No Idea How Bad Inequality Really Is

And if they did, they wouldn’t want European-style solutions.

Photo by Spencer Platt/Getty Images

If Michael Norton’s research is to be believed, Americans don’t have the faintest clue how severe economic inequality has become—and if they only knew, they’d be appalled.

Consider the Harvard Business School professor’s new study examining public opinion about executive compensation, co-authored with the Chulalongkorn University in Bangkok’s Sorapop Kiatpongsan. In the 1960s, the typical corporate chieftain in the U.S. earned 20 times as much as the average employee. Today, depending on whose estimate you choose, he makes anywhere from 272 to 354 times as much. According to the AFL-CIO, the average CEO takes home more than $12 million, while the average worker makes about $34,000.

In their study, Norton and Kiatpongsan asked about 55,000 people around the globe, including 1,581 participants in the U.S., how much money they thought corporate CEOs made compared with unskilled factory workers. Then they asked how much more pay they thought CEOs should make. The median American guessed that executives out-earned factory workers roughly 30-to-1—exponentially lower than the highest actual estimate of 354-to-1. They believed the ideal ratio would be about 7-to-1.

“In sum, respondents underestimate actual pay gaps, and their ideal pay gaps are even further from reality than those underestimates,” the authors write.

Americans didn’t answer the survey much differently from participants in other countries. Australians believed that roughly 8-to-1 would be a good ratio; the French settled on about 7-to-1; and the Germans settled on around 6-to-1. In every country, the CEO pay-gap ratio was far greater than people assumed. And though they didn’t concur on precisely what would be fair, both conservatives and liberals around the world also concurred that the pay gap should be smaller. People agreed across income and education levels, as well as across age groups.

This is the second high-profile paper in which Norton has argued that Americans have a strikingly European notion of economic fairness. In 2011, he published a study with Duke University professor Dan Ariely that asked Americans how they believed wealth should be split up through society. It included two experiments. In the first, participants were shown three unlabeled pie charts meant to depict possible wealth distributions: one that was totally equal; one based on Sweden’s income distribution, which is highly egalitarian; and one based on the U.S. wealth distribution, which is wildly skewed toward the rich. (They used Swedish income data as a model, rather than wealth, to strike a “clearer contrast” with the United States.)* Then, the subjects were told to pick where they would like to live, assuming they would be randomly assigned to a spot on the economic ladder. With their imaginary fate up to chance, 92 percent of Americans opted for Sweden’s pie chart over the United States.

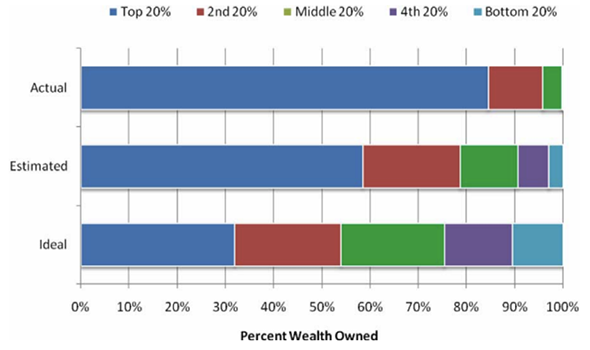

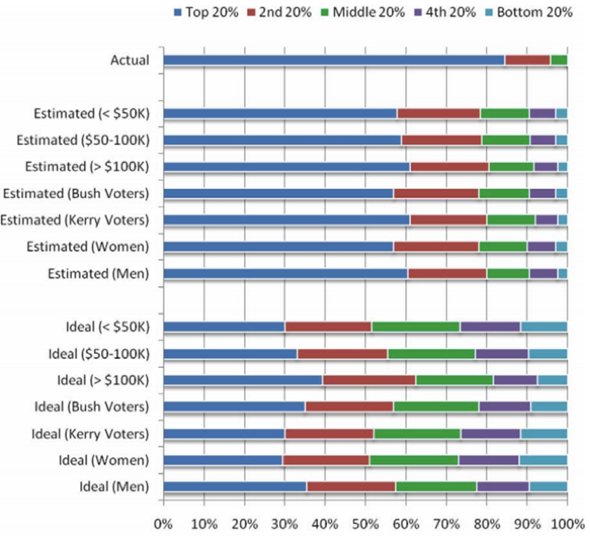

In the second experiment, Ariely and Norton asked participants to guess how wealth was distributed in the United States, and then to write how it would be divvied up in an ideal world (this, it seems, served as the template for Norton’s most recent study). Americans had little idea how concentrated wealth truly was. Subjects estimated that the top 20 percent of U.S. households owned about 59 percent of the country’s net worth, whereas in the real world, they owned about 84 percent of it. In their own private utopia, subjects said that the top quintile would claim just 32 percent of the wealth.

As in Norton’s more recent study, responses varied a bit by age, income, and political party, but there was overall agreement that America would be better off with a smaller wealth gap.

“People drastically underestimate the current disparities in wealth and income in their societies,” Norton told me in an email, “and their ideals are more equal than their estimates, which are already more equal than the actual levels. Maybe most importantly, people from all walks of life—Democrats and Republicans, rich and poor, all over the world—have a large degree of consensus in their ideals: Everyone’s ideals are more equal than the way they think things are.” Theoretically, Americans aren’t exceptional in their views about distribution at all—they have a sense of fairness similar to that of Germans, French, and Australians, and most Americans would be offended if they actually knew the degree of economic inequality that exists in this country.

But let’s say all of America woke up one morning and could cite Thomas Piketty chapter and verse. Would today’s moderates suddenly demand Scandinavian tax rates and mass wealth redistribution? Would our politics become more progressive?

It’s one thing to talk about fairness in the abstract; it’s another to agree on policies that would address it. Gallup, for instance, has consistently found that a solid majority of Americans believe wealth should be distributed more evenly. But fewer support the idea of imposing heavy taxes on the rich in order to do it. The Pew Research Center reports that 45 percent of Republicans already believe the government should at least do something to reduce inequality. But good luck finding GOP voters who are begging for a more robust welfare state.

Americans broadly support ideas that don’t require them to make an obvious personal sacrifice, like raising the minimum wage; they’re less happy to make tradeoffs. Europeans have long had social democracy baked into their politics; we have a libertarian streak. Maybe that would change if more Americans knew just how dire inequality has become. But I wouldn’t bank on it.

*Correction, Oct. 2, 2014: This article originally misstated that one of the pie charts in Norton and Ariely’s 2011 study was based on Swedish wealth data. It was based on Swedish income data. (Return.)