Double Lives

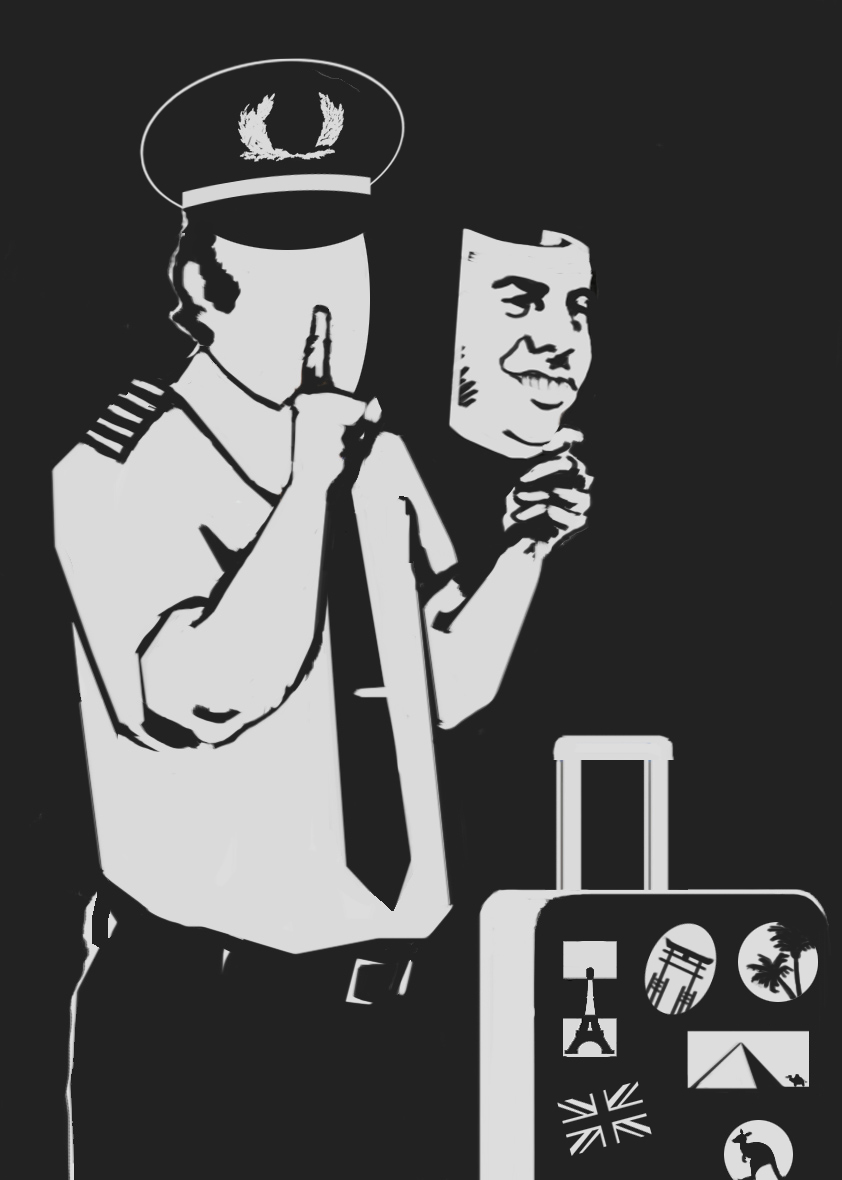

From politicians and CEOs to athletes and scientists, the news is filled with stories of people living double lives. The city mayor/ drug user. The investment banker/ mastermind of fraud. The golfer/ serial cheater. The nuclear physicist/ Russian spy. The aviator/ husband and father of a shadow second family. The list goes on and on.

What drives people to create and a hide an alternate persona? Why would they subject themselves to the psychological and emotional stress of sustaining a complicated web of lies over decades? How do they get away with it? And what happens when they don’t?

Born to Lie (and Cheat)

To answer these questions, we have to go back—way back—to that moment when, as kids, we first realized we didn’t have to come clean. Broken vase? The dog. Empty cookie jar? Your sister. Humans, it seems, are hard-wired to deceive. Studies have found that lying is actually a cognitive skill connected to higher-order thinking and reasoning—in other words, you have to know how to lie in order to know how to tell the truth. The ability to lie plausibly at an early age can actually be an asset: According to a study by the Institute of Child Study at Toronto University, children who lie as early as age two may grow up to be more successful than later liars.

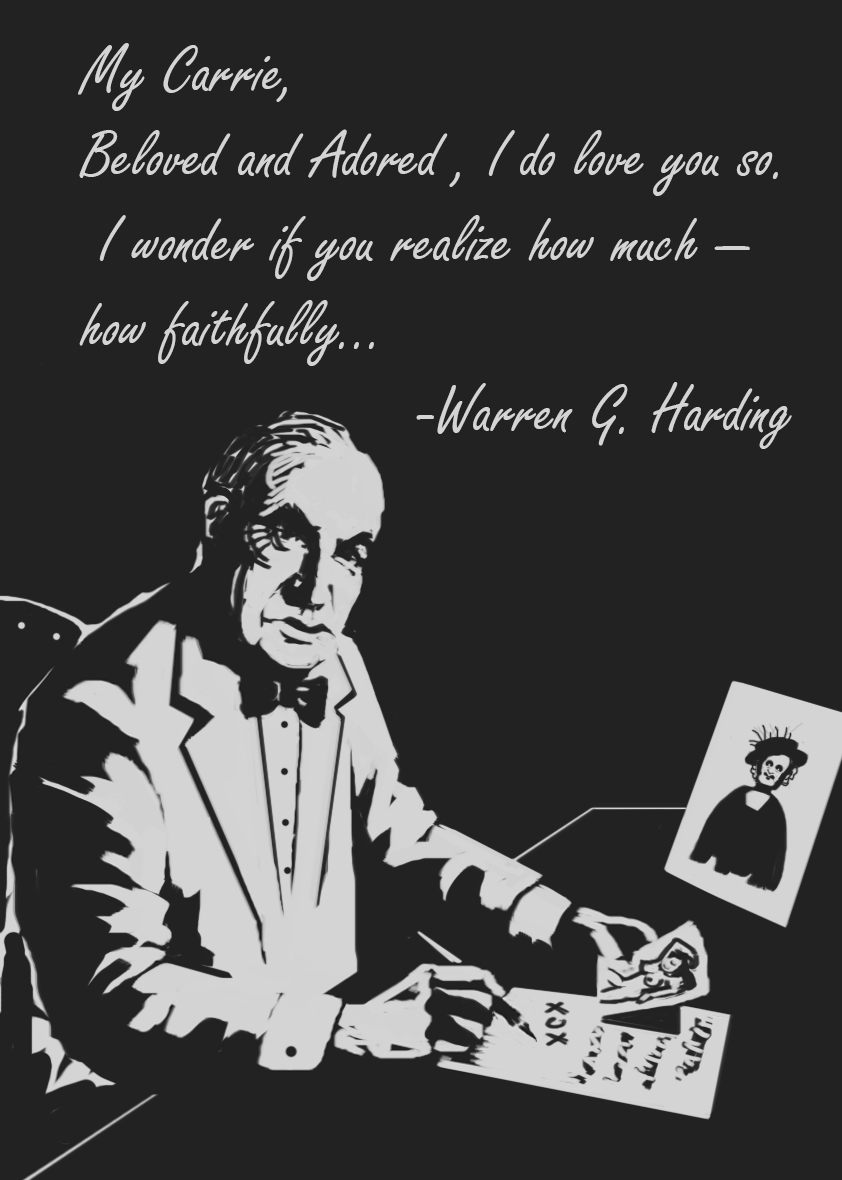

And sneaking around? Well, that may be hard-wired, too. Recent studies have shown that even monkeys have "affairs" and try to hide them. While statistics vary according to sources, the number of men and women who cheat on their spouses could be over 50%. A key factor is power, which, according to recent research, enhances people’s faith in their ability to successfully attract potential sex partners. This could be why cheating seems to be so rife in hothouse environments with clear power hierarchies: Political offices, for example, or a scientific think-tank like the Manhattan Project.

Secrets Vs. a Secret Life

Once we master the skill of lying, we get to experience the power of keeping secrets. We learn to withhold information to make people happy (like a birthday gift), to get out of trouble, to experience excitement, to avoid feelings like shame, to protect other people and to get what we want. We learn that sometimes we get caught and sometimes we don’t—and we figure out the behaviors, words and strategies that will tip the scales in our favor. The motivations for keeping secret lives are the same as for keeping simple secrets. The difference, psychologists say, is just a matter of degree.

Lying for the Cause

What about those those who don’t seem to be motivated by personal gain—like the Nazi industrialist who risked his life and fortune to shelter his Jewish factory workers? Consider the Manhattan Project scientists, who remain committed to working for years in an atmosphere where, as a chemist’s daughter put it, “One of the things you never knew… [was] exactly was what your father did.” Security was said to be so tight at Los Alamos that when one physicist got married, neither his or his wife’s parents were permitted to attend.

The answer, as reported by Slate, could be that people who endure danger in support of their beliefs may be less risk-averse, more adventurous, less driven by a need for security and more empathetic than the general population. Experts divide lies into three categories: those we tell for our own benefit, those that benefit someone else and those that benefit both ourselves and others. For example, while members of the Manhattan Project team were earning an income from their work, they were also driven by scientific curiosity and a desire to contribute to the common good by preventing the globalization of fascism.

Getting Away With It

Lying—and lying chronically for years—can have serious mental and emotional consequences. The act of trying to suppress a secret actually makes it harder to do—in the way that telling yourself not to think of a pink elephant makes you immediately think of a pink elephant. The minds of people leading double lives may be increasingly flooded with constant unwanted thoughts, leading to stress, anxiety and tension. While some people are able to manage the stress by disassociating from, repressing or rationalizing their behavior, for many, the dual lifestyle unravels when the pressure becomes so great that they reach a boiling point and confess their deception—or the lies become so complex that mistakes are made and their secrets are exposed.

Detecting Lies

In reality, most of us are more likely to read about people leading double lives than to come face-to-face with them ourselves. But since we do hear as many as 200 lies a day and we detect them with just 54% accuracy, it can’t hurt to watch out for these signs of untruth.

- Oversimplified stories told in strict chronological order. This helps liars keep details straight, while in a truthful account, we may start with an emotional detail and jump around in time.

- Bolstering phrases like, “To be honest,” and “Truthfully speaking.” These aren’t necessary when we’re really telling the truth.

- Movements that contradict words: When we’re concentrating hard on keeping a story straight, we may inadvertently nod “yes” even while we’re saying “no.”

- Verbatim repetition of a question: We often repeat part of a question before answering it. But liars repeat the whole thing to buy themselves time to prepare a deceptive reply.

- Lopsided or partial shoulder shrug: In a movement that genuinely means “I don’t know” or “I don’t care,” people raise both shoulders fully and symmetrically. A lopsided or tentative half-shrug could indicate deception.