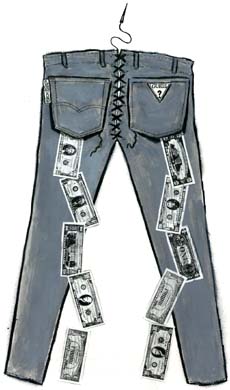

All in the Jeans

Levi's plays it clean, Guess plays it dirty, but they both lose in the hipness game.

Let me tell you a story about jeans. Actually, let me tell you a story about two companies that sell jeans. One of them, Levi Strauss, is about the best that American capitalism has to offer both in terms of ethical business practices and the way it treats its workers. The other, Guess Inc., is about the worst, notorious for its maltreatment of its workers and its ruthlessness in business. Now, if this were a story with an ending written by social democrats, Levi's would be rewarded and Guess would be punished. And if this story had an ending written by neoclassical economists, Guess would triumph and Levi's would pay the price for its attempt to evade market imperatives. What makes the story interesting, though, is that young consumers are writing it, and so it ends with two companies doing business in polar ways but arriving at exactly the same place: somewhere behind the curve.

Levi's is the world's largest clothing manufacturer, doing $7 billion in sales every year. It is also one of the few privately held large companies left in the United States, thanks to a management-led leveraged buyout in 1985. Since the LBO, which followed a year in which the company saw its earnings drop by 97 percent, Levi's economic performance has been outstanding, thanks in no small part to the rebirth of the 501 Buttonfly and, unfortunately, the remarkable success of Dockers. A recent outside appraisal of the company placed its market value at somewhere near 105 times what it was in 1984, a growth rate analogous to that of companies like Microsoft and Oracle.

In the past couple of years, though, Levi's has struggled. Overall sales have slowed, and its share of the men's jeans market has shrunk from 48 percent in 1990 to 26 percent in 1997. It would be great to see this decline as divine retribution for the invention of Dockers, but the answer has more to do with dramatic changes in the kinds of jeans kids buy and Levi's failure to adapt to those changes. At a time when kids influenced by hip-hop culture were buying jeans with legs as wide around as their waists, Levi's was still pushing its classic straight-leg look. And although it's now starting to push its baggy Silver Tab jeans hard, so-called private brands, marketed by department stores like J.C. Penney, are stealing the low end of the market while Ralph Lauren and his clones are eroding the high end. Levi's has become the dreaded "tweener," caught between the boomers and the echo-boomers.

The results have not been pretty. A month ago, Levi's announced that it would be closing 11 of its plants and laying off one-third of its North American work force, an astounding step for a company renowned for what its CEO called "long-term brand building, corporate social responsibility, and community involvement." Levi's workers have always been well paid relative to the industry as a whole, and the company has kept 55 percent of its manufacturing work force in Canada and the United States. In 1993, the company implemented Japanese-style production techniques in its sewing plants, breaking apart routinized assembly and giving individual workers more responsibility. Even Levi's severance package is impressive. With each laid-off worker receiving eight months' pay plus one week for every year of service, and company-funded retraining to boot, one union observer called it "by far the best severance settlement apparel workers have ever gotten."

Given all that, the easy way to understand what happened to Levi Strauss is to assume that its generosity caught up with it. If you employ unionized American workers instead of dollar-a-day Mexican workers, you will fail. But a look at its competition shows that Levi's main problem is not price cutting but image. Its largest competitor, VF, which makes Lee and Wrangler, charges only marginally less, and yet its market share has risen as Levi's has fallen. Retailers like Tommy Hilfiger and Ralph Lauren, whose jeans are not dramatically superior to Levi's in quality, are able to charge more simply because of their name. In the end, staying ahead of the style curve is both harder and more important than cutting costs.

A s evidence, one might want to look at Guess Inc., the jeans maker legendary for making Anna Nicole Smith a household name (well, in some households at least). Guess--there's a question mark at the end of the name, but typing it over and over is more annoying than you can imagine--was the hip jean of the 1980s, and it has spent most of this decade growing rapidly, both at home and abroad. Unlike Levi's, Guess has made its way in the world by subcontracting out production work, violating minimum-wage and maximum-hour laws, and suing everyone in sight. In the 1980s, for example, as part of a legal battle with Jordache, which at the time owned 50 percent of Guess, the Marciano brothers--who now own the company--set up a kickback scheme with contractors that ensured that money went to them and not to their partners. About the same time, they suborned an IRS agent into initiating criminal tax probes of Jordache's owners, probes that ended up going nowhere but were wonderful harassment devices.

In 1992, Guess paid the Labor Department $573,000 in fines for those minimum-wage and overtime-pay violations, and things seemed to have quieted down a bit within the bulletproof-windowed, razor-wire-surrounded stone building that serves as the company's bunker ... I mean, headquarters. But in the past year and a half, Guess has seen its stock price cut in half, had the only outside member of its board of directors quit after being on the job for a few weeks, and watched its chief financial officer resign for "personal" reasons. Meanwhile it has had a formal complaint filed against it by the National Labor Relations Board for firing 20 employees who were trying to organize a union, creating an in-house union to undermine those organizing efforts, and coercing workers into participating in an anti-union rally. It's capitalism with an inhuman face.

Coincidentally or not, Guess' earnings and revenue also have slid sharply, and what's interesting is that Guess' problems seem, in substance, almost identical to Levi's. Although the Marcianos are legendary for their abusive and intimidating management style--one former company CFO called Paul Marciano "psychotic" in a sworn affidavit--and for their habit of taking huge dividends out of the company's profits, they're not doing anything different today from the way they did business three years ago. They've always been crazy. It's just that now the Guess label has lost its cachet. The buzz is fading, and the company's jeans in particular, which a Fortune writer once said "made women look like Parisian hookers," seem like a vestige of a time when we read Less Than Zero and listened to Echo and the Bunnymen (which we may do still, but while wearing khakis). Without cachet, what does Guess have? Mostly, a really lousy labor-relations record.

So is the moral of the story that both the high road and the low road can take you into trouble if you stop paying attention to the taste makers? Partly. But the differences between the two companies--both, it's worth remembering, controlled by a small group of shareholders--also demonstrate that the choice of the high or the low road is a real choice. And our ideas of what constitutes a fair wage or a fair return on capital are historically contingent. Is a corporation supposed to net 12 percent of its sales or 20 percent? Should executives be paid 20 times the median wages of their employees or 300 times? The market does not dictate a universal solution to these questions, and so Levi's and Guess are able to answer them in very different ways. Unfortunately, in the face of the universal solvent of hipness, how you answer those questions seems to matter less than how you respond to this one: "So, do you have the 35-inch-wide legs or don't you?"