Drip, Drip, Drip

-

Jackson Pollock, CREDIT: One: Number 31, 1950, 1950. Oil and enamel paint on canvas 8' 10" x 17' 5 5/8". Sidney and Harriet Janis Collection Fund (by exchange). © 2010 the Pollock-Krasner Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Jackson Pollock, CREDIT: One: Number 31, 1950, 1950. Oil and enamel paint on canvas 8' 10" x 17' 5 5/8". Sidney and Harriet Janis Collection Fund (by exchange). © 2010 the Pollock-Krasner Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New YorkSoon after WWII, New York overtook Paris as the capital of modern art, Abstract Expressionism was the form of its triumph, and the Museum of Modern Art emerged as its temple. Through next April, MoMA has cleared its entire fourth floor for a show of nearly all the AbEx work it owns: some 200 paintings, drawings, and sculptures. Earlier in the century, European surrealists and "non-objectivists" had abandoned representation for Jungian symbols and geometric shapes said to reflect the cosmic order. But the "New York School," as the AbEx painters were known, went further. "At a certain moment," critic Harold Rosenberg wrote in 1952, "the canvas began to appear to one American painter after another as an arena in which to act—rather than as a space in which to reproduce, re-design, analyze or 'express' an object." The result was "not a picture but an event," in which the artist-hero "took to the white expanse of the canvas as Melville's Ishmael took to the sea."

-

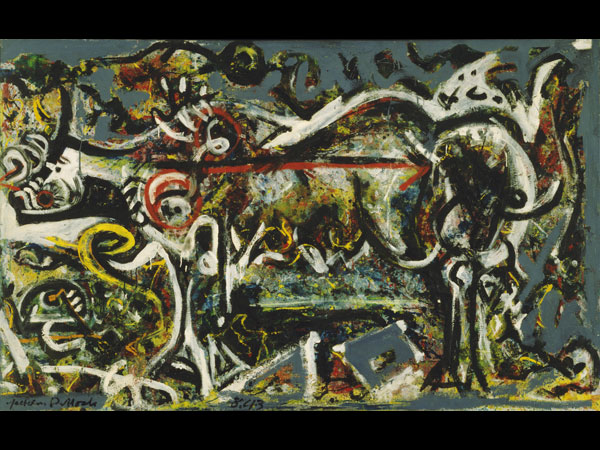

Jackson Pollock, CREDIT: The She-Wolf, 1943. Oil, gouache, and plaster on canvas 41 7/8" x 67". © 2010 the Pollock-Krasner Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Jackson Pollock, CREDIT: The She-Wolf, 1943. Oil, gouache, and plaster on canvas 41 7/8" x 67". © 2010 the Pollock-Krasner Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.MoMA's directors were slow to see AbEx as a distinct style, much less an era's signature. Not till 1958 (a decade after they were profiled in Life magazine) did the museum display its practitioners' art in a group show, called "The New American Painting," and by then a still newer American art was about to Pop. Still, the curators "got" Jackson Pollock—the group's grand and tragic icon—right away, buying The She-Wolf at his first solo gallery show in 1943. Earlier that year, at a Spring Salon for artists under 40, Pollock was singled out by several artists and critics, including Piet Mondrian, for his Stenographic Figure. But that painting was almost cartoonish—Miró on steroids—compared with She-Wolf, which was dark, turbulent, reeking of taboo: a transitional piece, studded with the totemic hieroglyphics of his earlier work but meshed with the stained colors and "all-over" lines (filling the entire canvas, no center or periphery, everything equally prominent) of the giant "drip" paintings to come.

-

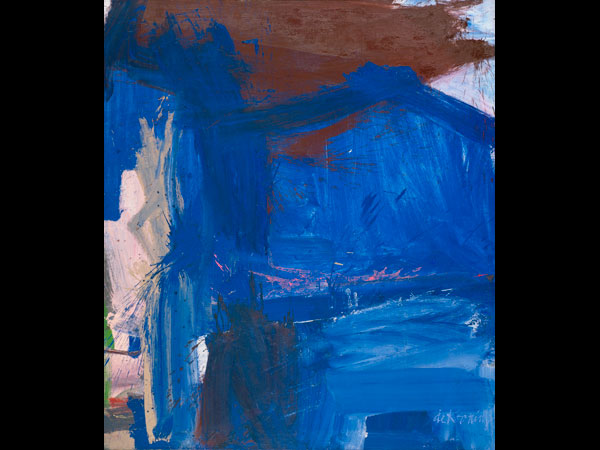

Willem de Kooning, CREDIT: A Tree in Naples, 1960. Oil on canvas 6' 8 1/4" x 70 1/8". The Sidney and Harriet Janis Collection. © 2010 the Willem de Kooning Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Willem de Kooning, CREDIT: A Tree in Naples, 1960. Oil on canvas 6' 8 1/4" x 70 1/8". The Sidney and Harriet Janis Collection. © 2010 the Willem de Kooning Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.One thing about a big museum show like this: You're staggered by how much great stuff has been languishing in the basement. Pollock's She-Wolf hasn't seen daylight in years. Neither have several paintings by his rival-comrade, Willem de Kooning, including this spectacular splash of color, A Tree in Naples. These omissions can distort the story of an artist's evolution. In de Kooning's case, the standard MoMA narrative covers the ferocious slashes of the early-'50s Woman series and the languorous swirls of the '80s (both great in their ways) with little in between. Who knew the collection included any of his landscapes! De Kooning was one of the few AbEx artists (another was Joan Mitchell) who swooned over nature, but, unlike the Impressionists, he painted not the scenery but the feeling that it washed over him. Few artists of any era painted color so sensuously: such deep indigo blues, such fleshy pinks, such sun-hazed yellows; and look at that corner pocket of verdant green.

-

CREDIT: Robert Motherwell, Elegy to the Spanish Republic, 108, 1965-67. Oil on canvas,

CREDIT: Robert Motherwell, Elegy to the Spanish Republic, 108, 1965-67. Oil on canvas,Some critics and a few of the artists themselves explained AbEx in political terms: as a product of the atom bomb, radio, the airplane, and the anxieties of modern life. Maybe. Certainly these shocks of the new accounted, to some degree, for the art's popular appeal or at least curiosity. But the artists themselves were interested mainly in form. Much as they sought to break away from tradition, they incessantly studied the great artists of the past. Robert Motherwell, the most intellectual of the AbEx artists, titled his most famous painting Elegy to the Spanish Republic, and its black swaths seem to convey a tale of hope snuffed out. But the painting isn't so different in form from his earlier, much brighter, sprightlierThe Voyage, which was inspired by a Baudelaire poem and greatly influenced visually by the Jazzcollages of Matisse, who, as Motherwell often said, inspired and moved him more than any other 20th-century artist.

6' 10" x 11' 6 1/4". Charles Mergentime Fund. © Dedalus Foundation Inc./Licensed by VAGA, New York. -

Mark Rothko, CREDIT: No. 16 (Red, Brown, and Black), 1958. Oil on canvas 8' 10 5/8" x 9' 9 1/4". The Museum of Modern Art, New York, Mrs. Simon Guggenheim Fund. © 1998 Kate Rothko Prizel & Christopher Rothko/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Mark Rothko, CREDIT: No. 16 (Red, Brown, and Black), 1958. Oil on canvas 8' 10 5/8" x 9' 9 1/4". The Museum of Modern Art, New York, Mrs. Simon Guggenheim Fund. © 1998 Kate Rothko Prizel & Christopher Rothko/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.Mark Rothko was the ultimate form-obsessed painter, finding his niche of personal expression, in the late 1940s, in slabs of rectangles, each painted a color that contrasts with, or merges into, the color above or below—until, by the late '60s, as a prelude to suicide, he narrowed his palette to dark gray and pitch black. But in the middle years, Rothko produced nerve-tingling works. No. 16 (Red, Brown, and Black) is one such marvel, as is No. 37/No.19 (Slate Blue and Brown on Plum), both done in 1958. He once said he was trying to capture that moment "towards nightfall," when "there's a feeling in the air of mystery, threat, frustration—all of these at once." Get up close to these paintings: The colors shimmer, they float on air. When MoMA acquired its first Rothko, No.10, in 1950, one of the museum's board members resigned in protest. I hope someone shouted, "Good riddance!"

-

David Smith, CREDIT: Australia, 1951. Painted steel, 6' 7 1/2" x 8' 11 7/8" x 16 1/8". The Museum of Modern Art, New York, gift of William Rubin. © Estate of David Smith/licensed by VAGA, New York, N.Y.

David Smith, CREDIT: Australia, 1951. Painted steel, 6' 7 1/2" x 8' 11 7/8" x 16 1/8". The Museum of Modern Art, New York, gift of William Rubin. © Estate of David Smith/licensed by VAGA, New York, N.Y.It's a cliché to say that modern sculpture is like a painting in space, but there's no keener description of David Smith's Australia, an abstract portrait (so it's said) of a kangaroo in motion, made of thin rods and steel plates for a truly breathtaking balance of fleet airiness and heft. Smith started out as a painter, then switched materials after seeing Picasso's welded sculptures, but his style was influenced more by his AbEx friends, most of whom lived (and drank and quarreled and caroused) in what is now called the East Village. In one of the MoMA show's most inspired juxtapositions, Australia is installed in the Pollock gallery, adjacent to Number 7, 1950, a canvas with similarly jagged lines and almost exactly the same width, to highlight the common atmosphere these artists shared and the influence that the unpolished power of Primitive art had on many of them.

-

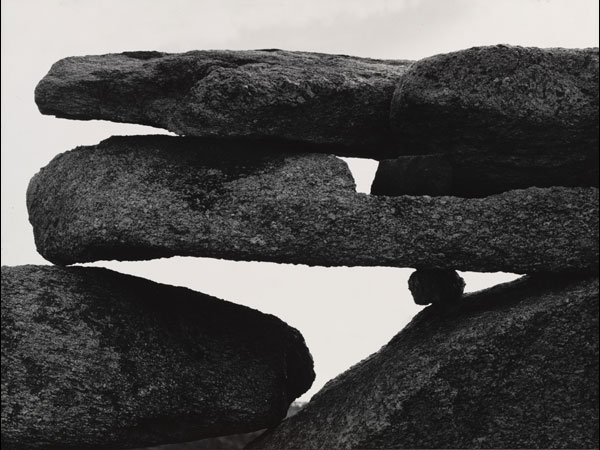

Aaron Siskind, CREDIT: Martha's Vineyard, 1954-59. Gelatin silver print, 12 7/16" x 16 1/2". The Museum of Modern Art, New York. © 2010 Estate of Aaron Siskind.

Aaron Siskind, CREDIT: Martha's Vineyard, 1954-59. Gelatin silver print, 12 7/16" x 16 1/2". The Museum of Modern Art, New York. © 2010 Estate of Aaron Siskind.One of the show's surprises is a room of photographs, a medium not generally associated with Abstract Expressionism, and, it must be said, not all these photos make a case for inclusion—but those that do are a revelation. A few by Robert Frank are illuminating: the profile of a car, light reflecting off its roof against a twilit sky; the center line streak of a narrow New York City avenue, like a Barnett Newman "zip" painting, vanishing into the horizon. Frank's approach to picture-taking—"fast bold sure eminently unfussy," as Walker Evans put it—owed much to the AbEx painters' spontaneous brushstrokes, but it's an eye-opener that he so often took inspiration from their images, too. Most striking, though, are Aaron Siskind's shots of nature and architecture: peeling paint, Chicago street murals, and especially a staggered stack of stones in Martha's Vineyard that would fit right in with paintings by Franz Kline, Arshile Gorky, or Adolph Gottlieb.

-

Clyfford Still, CREDIT: 1944-N No. 2, 1944. Oil on canvas, 8' 8 1/4" x 7' 3 1/4". The Museum of Modern Art, New York, the Sidney and Harriet Janis Collection. © Clyfford Still Estate.

Clyfford Still, CREDIT: 1944-N No. 2, 1944. Oil on canvas, 8' 8 1/4" x 7' 3 1/4". The Museum of Modern Art, New York, the Sidney and Harriet Janis Collection. © Clyfford Still Estate.The most eccentric Abstract Expressionist painter by far was Clyfford Still. Fanatically uncompromising, he regarded Europe's artistic traditions as a "totalitarian hegemony" that must be erased entirely. He didn't merely paint, he encrusted his canvases with thick black paint, punctuated by a thin streak of yellow or a lighting bolt of red. (Rothko pronounced Still's paintings to be "of the earth.") By choice, he sold only a few of his works in his lifetime, leaving behind more than 1,000 large paintings, rolled up, unseen, with instructions that they be shown only in a museum dedicated to exhibiting his works exclusively. A decade ago, some donors took up the challenge and are now erecting a Clyfford Still museum in Denver. MoMA owns just two Stills, and they are mesmerizing: the arrestingly austere 1944-N No. 2 and the more lavish 1951-T No. 3. By "lavish," I mean it has a few whole swaths of color. 1951 must have been a jolly year.

-

Grace Hartigan, CREDIT: Shinnecock Canal, 1957. Oil on canvas, 7' 6 1/2" x 6' 4". The Museum of Modern Art, New York, gift of James Thrall Soby. © 2010 the Estate of Grace Hartigan.

Grace Hartigan, CREDIT: Shinnecock Canal, 1957. Oil on canvas, 7' 6 1/2" x 6' 4". The Museum of Modern Art, New York, gift of James Thrall Soby. © 2010 the Estate of Grace Hartigan.Another surprising thing about this comprehensive show is not just how many artworks but how many artists—in some cases, major artists—even a frequent visitor has almost never seen at MoMA until now: Sam Francis, Helen Frankenthaler, Alfred Leslie, Joan Mitchell (her explosive Ladybug really should be on permanent display), and, not least, Grace Hartigan, whose Shinnecock Canal, a festive pastiche of scribbles and bold colors, is an eye-opener. Hartigan was a "second-generation" AbEx painter and a saucy proto-feminist in a macho, male-dominated art world—the only woman featured in MoMA's 1958 show on "The New American Painting." Like de Kooning, she never abandoned figurative forms and, in the '60s, unlike any of her old colleagues, even drifted into Pop, incorporating pastel colors and images from comic books and advertisements.

-

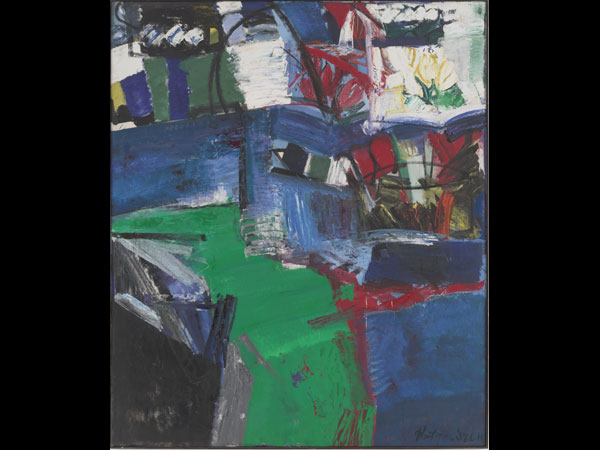

Hans Hofmann, CREDIT: Memoria in Aeternum, 1962. Oil on canvas, 7' x 6' 1/8". The Museum of Modern Art, New York, gift of the artist. © 2010 Renate, Hans & Maria Hofmann Trust/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Hans Hofmann, CREDIT: Memoria in Aeternum, 1962. Oil on canvas, 7' x 6' 1/8". The Museum of Modern Art, New York, gift of the artist. © 2010 Renate, Hans & Maria Hofmann Trust/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.The show starts and finishes with works by Hans Hofmann, the undersung leader of AbEx, whose art school on West 8th Street* served as a rallying point (along with the nearby Cedar Tavern) for the new New York painters. At the start is Spring, a small oil on wood, dated 1940, that experimented with "drip" before anyone had heard of Jackson Pollock. Near the end is Memoria in Aeternum, a large canvas that, with a wistful energy, pays homage to the entire span of Abstract Expressionism—the drips, stains, long gestural strokes, and Hofmann's own geometric forms. (See his nearby Cathedral.) It tolls not just the deaths of several artists but the eclipse of their artistic movement. Hofmann painted it in 1962, the year of Andy Warhol's first New York gallery show, the taking-hold of Pop, and, with that, the re-emergence of everyday life as a suitable subject for art, this time imbued with an ironic lilt, which undermined the AbEx image of the artist-hero who paints some inner reality on the canvas, liberating himself from the world around him.

Correction: The article originally stated that Hofman's school was on East 8th Street.

-

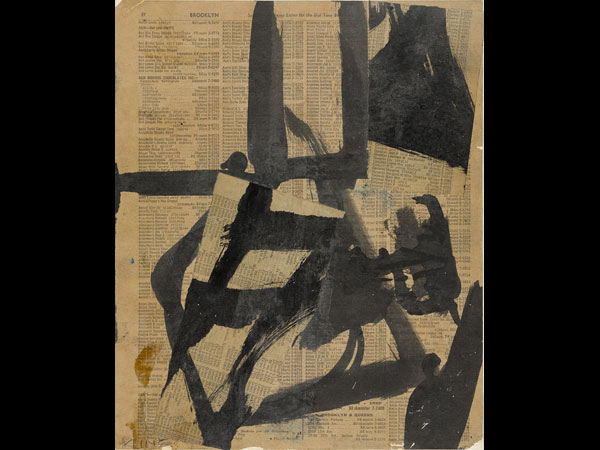

Franz Kline, CREDIT: Untitled II, c. 1952. Ink and oil on cut-and-pasted telephone-book pages on paper on board, 11 x 9". The Museum of Modern Art, New York. © 2010 the Franz Kline Estate/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Franz Kline, CREDIT: Untitled II, c. 1952. Ink and oil on cut-and-pasted telephone-book pages on paper on board, 11 x 9". The Museum of Modern Art, New York. © 2010 the Franz Kline Estate/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.Out in the fourth-floor lobby are works by some of the artists who came next (Warhol, Lichtenstein, Rosenquist, Johns), exiled from the galleries by this celebration of their predecessors. But just as the Abstract Expressionists took much from Surrealism and Impressionism while breaking out of their orbit, so the Pop artists did the same with AbEx. Franz Kline's Untitled II, done in 1952, slashed strokes of ink and oil paint on cut-and-pasted pages from a phone book—an update of Picasso's collage but also a forerunner of Robert Rauschenberg's "found objects." Pollock's Full Fathom Five (1947) contains nails, tacks, buttons, coins, cigarettes, and a key embedded in its canvas, to thicken the texture. Rauschenberg, who revered de Kooning, once famously erased a de Kooning drawing, but a wispy glow remained. The line between movements and eras is rarely clear-cut. In art, as in politics, revolution and tradition overlap more than either set of partisans likes to believe.