Girl, where do you think you’re goin’?

Where do you think you’re goin’, goin’, girl?

That plea is the chorus of “Joanne,” the title track of Lady Gaga’s new album. Sung in a creaky voice that sounds at once millennial and aged, over acoustic guitar and hand percussion, it is a loving, lonesome cry across the mortal divide to her father’s sister, Joanne. She was an aspiring poet and painter who died before Gaga was born but remains a continuous inspiration, even a spirit guide. (It may align with the theme of artistic inheritance that the guitar is by Harper Simon, son of Paul.)

But “Where do you think you’re goin’?” is also a question for the singer herself, who takes one of her middle names from her late aunt. On Joanne, the album, the most theatrical figure in a decade of highly stylized pop divas reckons at age 30 with where Lady Gaga ends and Stefani Joanne Angelina Germanotta begins. She wants the public to know that, beneath that meat dress, there was always skin and bone.

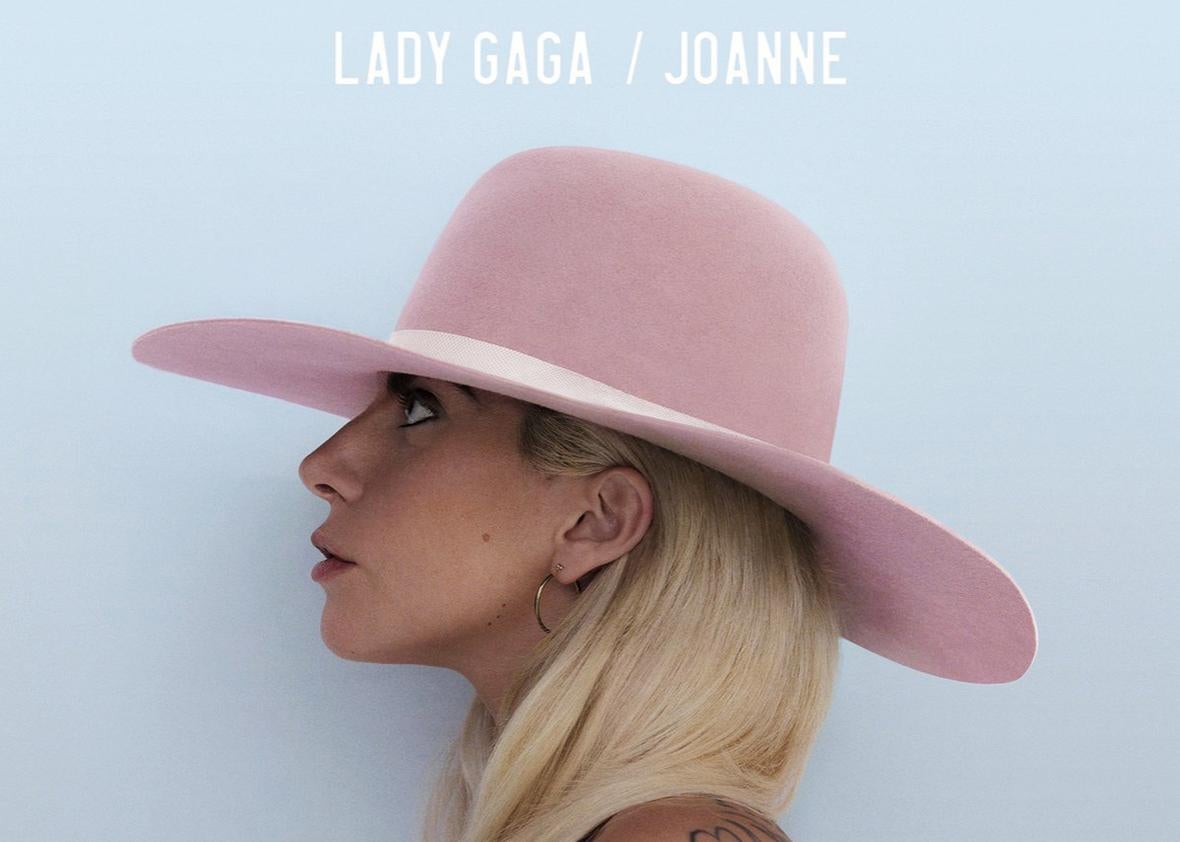

Its plain-faced cover profile is of Germanotta, unadorned except for a floppy, retro, pink hat. Joanne sheds Gaga’s Dada “monster” costumery and cosmetics along with much of her cybernetic sound. Instead it presents a kind of trans-Atlantic roots-pop cabaret, part Nashville and part Elton John. It was produced mainly with Mark Ronson, the U.K. vintage-sound restoration specialist renowned for his work with Amy Winehouse and on “Uptown Funk” with Bruno Mars. Other collaborators (primarily the producer BloodPop, formerly known as Blood Diamonds) drop in to smear electronic rouge and aquamarine around the songs’ contours.

It has the fun, boot-scootin’ cowboy-funk of tracks such as “A-YO” and “John Wayne.” It has the New Wave–meets–arena-rock of “Diamond Heart” and the first single “Perfect Illusion.” (An unfortunate strategic choice, because it’s more of a leftover-meatloaf than most of the songs here, not least because it swipes its title hook from the “keepin’ my baby” line of Madonna’s “Papa Don’t Preach.”) It has more earnest modern country in “Million Reasons” and “Sinner’s Prayer,” written respectively with Nashville songwriter Hillary Lindsey (responsible for Little Big Town’s 2015-conquering “Girl Crush” and much of Carrie Underwood’s catalog) and the indie-folk artful dodger Father John Misty. Misty also had a hand in the electro-barrelhouse-piano peace-and-lovin’ of “Come to Mama,” which is material Janis Joplin might have sung if she’d lived to mellow into the mid-1970s. It even has several arresting guitar interludes from Josh Homme of the stoner-rock stalwarts Queens of the Stone Age. That’s a meeting neither artist’s core fans ever might have predicted, or welcomed.

Naturally there are also morsels for the “Little Monster” loyalists. The she-bop, self-pleasure anthem “Dancin’ in Circles,” with its “Alejandro”-like Spanish-island lilt, could have been on 2009’s Fame Monster EP, though it also genuflects to the recent “tropical house” trend. (It was co-written with a po-mo collagist of a previous generation, Beck, though his touch is all but undetectable in this version.) But mostly she is asking fans to move on, alongside her.

There’s always been a slippage of timelines in Gaga’s career. Plenty of young artists end up singing obsessively about celebrity after it’s happened to them. She made it her targeted métier from the start, calling her first dance-pop album The Fame in 2008. She became more socially forward-thinking with Born This Way in 2011, which established her totemic role in the LGBTQ community, while calling back musically to the new-pop 1980s of Madonna, Prince, and Springsteen. When the music business expected her to consolidate her hit-making status in 2013, she released the experimentally dense rave-pastiche Artpop instead. Then she stepped back and made a turn more characteristic of stars who’ve aged well out of the Top 40 (such as Rod Stewart or, most recently, Nobel Laureate Bob Dylan). Her American Songbook standards album, Cheek to Cheek, matched her with the octogenarian eminence Tony Bennett. Now, instead of doing the big-pop-comeback thing with Joanne, she’s making a move toward intimacy and authenticity. Or at least a born-and-bred showbiz kid’s version of that.

On another level, though, her timing is consistently on point. The fame-deconstruction motif was in sync with the pop-diva apotheosis that was building late last decade. Larger-than-life young women such as Katy Perry, Rihanna, Miley Cyrus, and Beyoncé ascended like glam King Kongs to the top of the music industry’s teetering tower and (I-am-woman-hear-me) roared, especially on social media. Gaga brought a meta-pop conceptualism to that moment in a way that quickly made her the darling of pop-culture academics. (The online journal Gaga Stigmata, active from 2010-14, proudly called itself “the first mover in Gaga studies.”) She was ahead of the wave of this decade’s big ’80s-music revival, thanks in part to her early involvement with the turn-of-the-century NYC “electroclash” movement. (She winks to it on the deluxe edition of Joanne with the tinny synth-horns of “Just Another Day,” though that’s balanced out by some Sgt. Pepper bounce). And even Artpop, perceived as a commercial and critical nadir, was her way of wading into the tension at the time about whether the energy center of youth music culture was in the mainstream charts or at club parties and EDM festivals.

The jazz-duets album was more of a pause-and-reset, intended to certify her as a more traditional singer and musician rather than a spectacle machine. (Though it doubled as another assertion of her chameleonic changeability, not unlike her hero David Bowie singing Christmas carols with Bing Crosby in 1977.) It was also Gaga touching base with Stefani Germanotta’s performing-arts-high-school, Broadway-lover background. It enabled Joanne, which is the nearest commercially viable thing to a sequel to what she was attempting, with limited success, in her solo piano-and-voice performances in New York in the years before she invented Gaga.

The album begins by harkening back to those days with “Diamond Heart.” It immediately bolts attention by describing the go-go dancing work she was doing just out of school to make ends meet—as well as the sexual assault she endured at the hands of, she sings, “some asshole” who “wrecked all my innocence.” (She has spoken about this event before, and it informed the Oscar-nominated song “Til It Happens to You” that she co-wrote for the campus-rape documentary The Hunting Ground.) A harder, more mercenary self emerged, intent on making money but also on safeguarding her “diamond heart.”

Lady Gaga was a creative solution to Germanotta’s corneredness then. Joanne is in turn an escape from the dead ends the Gaga identity led to. Her fame-personae games were always warmed-over Andy Warhol, Bowie, Judith Butler, and Madonna theories with a 21st-century twist. As renewedly relevant as that seemed in 2009 and 2010, it’s all become way too obvious and kiddie-pool-level in the era of Snapchat and Instagram: Image and identity are constructed and malleable? Oh, do tell! “Authenticity,” too, is a clichéd way to break down such devices. Some of the rootsy gestures on Joanne are reminders that a truth-telling stance is always its own kind of artifice, with its own scripted formulae.

But the thing about autobiography is that, unlike abstract point-making, it tends to lead to specifics, and that’s often the redeeming factor here. Gaga’s duet with Florence Welch of Florence and the Machine, “Hey Girl,” risks being a lady-friendship anthem as generic as its Elton-and-Kiki-Dee (side-routed through “Bennie and the Jets”) template—until it reaches the bridge, which suddenly starts detailing, “Help me hold my hair back … And we danced down the Bowery/ Held hands like we were 17 again.” We don’t need to know if Gaga’s talking about a particular person there, but it’s not a bromide like the chorus’s “We can make it easy if we lift each other.”

There’s also a side to this step that is not merely personal but characteristically on top of the zeitgeist. When Taylor Swift made a huge show of switching allegiances from country to pop in 2014-15, it seemed to certify that megapop had achieved total dominance. Instead, as if Swift had thrown the cosmic forces out of balance, that great pop tide has been turning against itself ever since. As Slate’s Chris Molanphy has noted, this year has been marked by melancholy, downbeat hits from the Chainsmokers (with whom Gaga has feuded on Twitter), Twenty One Pilots, and Frank Ocean. The presence of BloodPop as a producer on Joanne is a reminder that he tooled Justin Bieber’s “Sorry,” part of a suite of head-down acts of contrition for pop hubris. Veterans such as Rihanna, Drake, and Kanye have bucked the pop playbook tactically and stylistically, and artists have become more outspoken about both private and societal anxieties, led by Beyoncé’s Lemonade.

You could look at Gaga’s Nashville salutes as commercial hedging (though, again, ahead of her age group), as it’s increasingly where white rockers’ careers go to retire in comfort. But in many ways I hear her “Sinner’s Prayer” as the deepest song here, a “bad girl” grappling with the intergenerational fallout of her relationship with her father (“a cruel king,” as she calls him on “Diamond Heart”). It’s parallel in style and theme with Beyoncé’s own country turn on Lemonade, “Daddy Lessons.” (“ ‘When trouble comes in town and men like me come around,’ my daddy said, ‘Shoot.’ ”) Maybe country simply reminds most girls of their dads, even across racial boundaries. But it’s also part of Gaga’s attempt here to catch up with the ever more explicit topicality, feminism, and anti-racism of the pop/anti-pop voice of 2016.

Unfortunately, her biggest reaches that way are the two weakest songs here, which suggest that pop-monster and singer-songwriter lyrical standards do not always mesh. The deluxe edition’s “Grigio Girls,” dedicated to a breast-cancer–suffering colleague in her Haus of Gaga artistic team, is a bachelorette-party–style girl-power anthem, and also a raucously vapid chunk of garbage. Worse is her entry into the ranks of police-brutality–protesting, Black Lives Matter solidarity songs, “Angel Down.” From the title to the synthesized harp glissandos, it traffics in a sentimentalization of political and racial anger that becomes cringeworthy (in the way, for instance, that it juxtaposes “the age of the social” with “the arms of the sacred”).

On the deluxe edition, however, there is a bonus “work tape” take of “Angel Down” that, startlingly, kind of works. It’s less flounced up in audio taffata, and Gaga’s vocals are throaty and heartfelt, on a sonic plane that’s been sanded out of the official version. Indeed, it summons up a fantasy alternative version of Joanne, an album that for all its varied enticements never quite gels into the declarative statement it aspires to. There’s an anxiety in it, nudging, Do you like me this way? Do you care about me like this? As transitional albums go, it’s undeniably a charming one. But its brightest promise springs from where we imagine this girl, this woman, this Gaga-Germanotta, might be goin’, goin’ next.