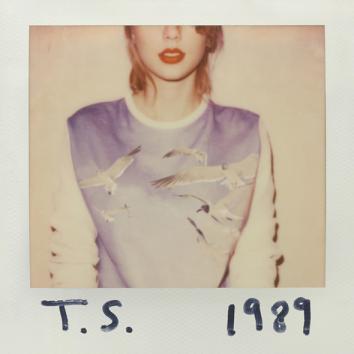

Contemplating Taylor Swift’s Navel

A deep gaze into 1989, 1989, and the mystery at the center of the world’s biggest pop star.

Photo illustration by Slate. Photos by Mark Davis/Getty Images, Kevin Winter/Getty Images for CBS Radio Inc., and Ethan Miller/Getty Images for iHeartMedia.

As to the Lord above with his eye on the sparrow, to a celebrity fashion blogger no detail is too minute to notice. Thus this summer the Cut, as well as Perez Hilton, took note that “There’s No Proof Taylor Swift Has a Belly Button.” Notwithstanding the crop tops, slit skirts, and cleavage the 24-year-old singer has been rocking as she molts from vanilla-malted country star to demi-caliente adult pop supernova, they observed, none of her outfits ever discloses the physical evidence that the Snow Queen of Pop was once of woman born. (Specifically of Andrea Gardner Swift, née Finlay.)

The irony is both obvious and irresistible, just like a good Taylor Swift lyric: The songwriter famous for her diaristic “navel-gazing” does not permit any glimpse of her actual abdominal dent.

After much foreshadowing, Swift’s fifth studio album, 1989, her vaunted conversion from country-pop to pop-pop, finally debuted this week, to messianic-level marketplace expectations and to the rapture of fans like (and unlike) me. It is being pored over for all kinds of clues, but no one is sleuthing the mystery of the missing belly button. Which makes sense because the solution is no doubt prosaic (strategic modesty, or possibly outie). But the symbolism is, as Swift might say, epic.

Note: I realize it’s dicey to use a body-centered metaphor to discuss a young female artist, and one who distances herself from the anatomical foregrounding in contemporary pop at that. But in art, what’s elided is also part of the story. And culturally the navel plays several archetypal roles that (sometimes) transcend the flesh.

So as we gaze into 1989, let’s consider the many ways that Swift’s absent navel, like Nietzsche’s abyss, gazes back.

As Umbilical Nub

Swift’s prime talking point is that she titled the album 1989 after friends pointed out midway through its two-year gestation that it was sounding very ’80s, a note she ran with. Honestly, though, the width of this album’s shoulder pads has been exaggerated; there are as many touches from 1970s, 1990s, and 2000s pop, which is to say 1989 sounds precisely like a 2014 Taylor Swift album produced by Max Martin and Shellback.

Photos by Frederick M. Brown/Getty Images and courtesy of Protj/Wikimedia Commons

More vital is that 1989 is the year Swift was born (Dec. 13). As she’s said, the title declares her symbolic rebirth, severing the umbilical link to Nashville and the stylistic trappings of country. This is why “Shake It Off,” the first single, startling and addictive and horns-y, about dancing your reputation and inhibitions away, really ought to be the first song, too. Instead the dismally (and literally) jingle-like “Welcome to New York” is perhaps the lousiest opening track to a great album since “Radio Song” on REM’s Out of Time (1991). Still, Swift’s ode to doing a geographical does offer a curtain-raising rupture: Toto, we’re not in Nashville anymore.

The album title’s two meanings counterbalance each other: The ’80s framing story helps sustain the thread of quaintness and small-town nostalgia to which many of her long-term fans are attached. But the personal meaning is utterly about living in the big old city, about “someday” becoming now. Calling it 1989 is an alternative to calling it 24 or 25 (which might be confused with an album by Adele, her rival in sales and divadom), a stamped certificate that Swift is a grown-ass lady now.

As Median Point and Sore Spot

Reaching adulthood is perilous for a teen star. How do you replace that erstwhile guileless glow? The pattern in recent years, from Justin and Britney to Miley and Justin, has been for winsome Disney Channel poppets to claim their self-determination by aggressively projecting sexuality. But Swift neither wants nor needs to assert her autonomy so wildly—as a singer-songwriter, Taylor’s always seemed to be in charge of Taylor. The problem was who Taylor was.

As I discussed recently with fellow critic Sarah Liss, Swift’s brand for years has been a half-knowing, half-naive everygirlness. A privileged and sheltered kid who radiated middle-school self-consciousness, she found that tween-girl fans (and their parents) took to her blend of blushing and bluster like catnip. Swift had discovered a novel cross of teen pop’s slumber-party-secrets vibe with country’s technical craft, forthrightness, and courtesy.

In both Nashville country and white teen pop, the ability to project realness and approachability has always been a valuable currency—the sense that the artist could be your big sister or best friend, singing (in country at least) about her life, a life a lot like yours writ large, with hotter crushes and sparklier jackets and screaming stadiums. (The presumptive fans on either side are girls and women; straight boys’ feelings don’t count much, for once.)

By the time of 2012’s Red, though, she often was coming off a bit like a twentysomething actor stuck playing young and dumb on a high-school soap opera. That’s what made the reinvention (which began with that album’s “I Knew You Were Trouble” and “We Are Never Ever Getting Back Together”) so urgent.

As Jell-O Shot Dispenser

It might seem like a paradox: Pop reads as a younger and shallower style than country, which is classically “four chords and the truth” about grown-up problems, despite its recent plague of party anthems. But Swift didn’t want to mature all the way into mom jeans, at least not yet (after 30 it wouldn’t be hard to picture).

Going pop lets her act her actual age and, frankly, her stratospheric social class—more urbane and sharp-edged but also Instagram-filtered. It might mean streamlining her distinctive lyrical vocabulary (to the distress of some critics and fans), but it also means one of the biggest stars on the planet can drop the “Who, me?” face and go head-to-head, with her game face on, against pop peers and rivals.

Photo by Steve Marcus/Reuters

With the care and nurturing at which Swift is so deft, the fan coalition she forged won’t fall apart, country radio or no country radio. And now she need not be so wedded to lyrical naturalism—her mastery of it is one of the reasons I and many other listeners love her, but aesthetically it is a bit retro and hokey. She needs to expand her range.

It also means she gets to stop pretending a lot of things, whether that’s caring about mandolins or being the weaker sex: So many of Swift’s older songs are marred by the way she portrays herself as the victim in all the relationship dynamics, a passive way of getting revenge. That pattern has all but vanished on 1989, and that’s a benefit of ditching country parochialism for pop’s female-dominated fracas.

This is a coming-out party. As Swift sings on “New Romantics,” in the final words of the extended version of the album: “The best people in life are free.”* To go by 1989, Taylor’s take on 24 is a lot less “dress up like hipsters and make fun of our exes” (her idea of fun at “22”) and more like a boss: I’ve never believed her more completely than when she howls in “Shake It Off”: “I never miss a beat/ I’m lightning on my feet/ and that’s what they don’t see.”

She ain’t talking about dancing.

As Contemplative Locus

Like many people, I suspect, I for years held my own ideas about how Swift ought to mature, based on a creakier notion of “quality songwriting” than her industry-savvy one. I noted her love for the likes of Joni Mitchell and Emmylou Harris as narrative singers of female experience, but also the way her everygirlness was innately political: It tried to enunciate the subjective experience of being a 21st-century suburban girl, in the manner of a subversive YA novelist. She didn’t grasp what feminism was yet, and she definitely wasn’t always doing it to the satisfaction of the coastal elites, but at base she leaned that way.

As her talent developed I thought she might become a kind of arena-scale, millennial Tori Amos, singing thorny, complex songs of young womanhood, like a tuneful version of the young feminist essayists on sites such as the Hairpin and Rookie.

The person I wanted her to be, in retrospect, was Lorde. The antipodean teen-prodigy “Royals” singer was initially critical of Swift, but now they are friends. (Swift is a “keep your enemies closer” type.) In fact Swift does emulate Lorde’s diction and her pulsing-synth style in spots on 1989, such as the us-against-them brooder “I Know Places” and the manifesto-toned bonus track “New Romantics,” but to such a different effect that the songs seem better when you don’t try to compare them.

My forecasting errors were due to the fact that I’d bought into the “diary” model of Swift’s supposedly introspective songwriting process. I’m coming to think that’s nonsense. Swift is not very compelled by her navel as the yogic source of interior insight. She only cares that it’s the diaphragm zone a singer needs to project from. Swift is interested in impact.

As Camera Aperture

For years fans and media have treated Swift’s output as an unfolding roman à clef, obsessively cross-referencing her paparazzi-documented personal life with her song lyrics. And Swift has demurred while egging it on, most of all with the typographically coded “hidden messages” in her liner notes.

If you read the messages from 1989, they reinforce the impression from the lyrics (and dead giveaways like the title of “Style”) that much of the album is about Swift’s 2012 relationship with Harry Styles, the then-18-year-old singer from English boy band One Direction. There are repeated details about their on-off romance, especially references in several songs to a vehicle crash (on the record a car, in real life supposedly a snowmobile) and to Styles’ signature paper-airplane necklace.

Which is weird, because by all accounts the cumulative lifespan of this relationship was fruit fly–like. Swift may be melodramatic about her emotions, but could someone so high-functioning, even in her early 20s, be quite so unhinged about such a fleeting affair?

Listen to the tone of the messages: “WE BEGIN OUR STORY IN NEW YORK. … THERE ONCE WAS A GIRL KNOWN BY EVERYONE AND NO ONE. … HER HEART BELONGED TO SOMEONE WHO COULDN’T STAY.”

This is not a diary. This is a screenplay. Swift isn’t genuinely disclosing her intimate life, but harvesting scraps and rearranging them into a grander narrative. Who knows what really happened in these love affairs, if anything? As a thought experiment, let’s just imagine nothing did. For Swift, Harry Styles isn’t a lover but a prop, a figment, a flicker. I posit that this is her real achievement.

Consider the rollout of the early tracks on 1989, which is distinctly cinematic.

“Welcome to New York”: setting. “Blank Space”: casting (the “pen click” sound Swift perfectly drops into the chorus could be the click of a movie slate). “Style”: wardrobe and makeup. “Out of the Woods”: the plot begins to thicken. “All You Had to Do Was Stay”: the all-is-lost moment. Etc.

The arc gets messier—there are competing priorities in sequencing the biggest album of the year, after all—but it checks off all the boxes of a romantic drama. Swift seems to propose two possible endings—either a reunion montage set to “How You Get the Girl” followed by the gauzy denouement “This Love,” or a scenario in which the couple’s life get much too crazy (chased like foxes through “I Know Places”) and the girl finally swears off the boy like a bad addiction, as Swift says she’s lately done with dating in general (the lovely Imogen Heap duet “Clean”).

This model helps rescue “Welcome to New York.” As Molly Lambert recently commented on Grantland’s Girls in Hoodies podcast, it’s hard to hear Swift sounding like she knows nothing, because we love her best when she seems to know everything. But if she’s really the director and omniscient narrator, then it’s fine that her lead character starts off clueless, just like Anne Hathaway’s naif in the first reel of The Devil Wears Prada, so we can appreciate how much wiser (and sadder) she is by movie’s end.

The hypothesis that Swift’s purported private life is a total crock also sheds some light on the tech-privacy paranoia notoriously depicted in last month’s Rolling Stone profile, brilliantly parodied by the InfoSec Taylor Swift Twitter account: She does have secrets to keep, and she wants to be the one who controls the leaks and aims the cameras.

Of course, that control mania would be true even if her dating life were straight legit, as we witnessed during the cross-media but otherwise old-fashioned two-month gradual reveal and charm offensive that led up to 1989’s release. No trendy sneak-attack drop for her. Unlike Beyoncé, U2, or Thom Yorke, Swift has no use for a birth of Athena–like spectacle of instant genesis, because even when she makes music that leans on beats and synths instead of fiddles and guitars, her credibility is staked on authorship—her skills as notebook poet and bedroom tunesmith. For a fan base still wary of artifice, she needs to show her work.

That’s why on the deluxe version of 1989 there are spoken bonus tracks that document three songs’ beginnings as voice-memos to her collaborators. These serve to swaddle Swift’s ruthlessly professional, results-driven process in organic cotton pajama-party spontaneity and to vouchsafe that her private experience remains the bona-fide mother lode of her songs’ DNA.

Maybe yes, maybe no. But if 1989 is a movie, these are the DVD commentary tracks.

As Teen-Pop Erogenous Zone

Another standard contrast between pop and (usually) country is sexual forwardness, and while Swift has been easing off any pretense to chastity for a while now, the 1989 movie includes her first out-and-out sex scene, “Wildest Dreams”:

He’s so tall, and handsome as hell.

He’s so bad, but he does it so well …

I said, “No one has to know what we do.”

His hands are in my hair, his clothes are in my room.

“Wildest Dreams” has been written off widely as a Lana Del Rey rip-off musically and lyrically, but in context I take it as a deliberate exercise in bedroom dress-up and role-playing—“even if it’s just pretend.” It is not as if Del Rey herself is any stranger to imitation and disguise. Swift’s character takes satisfaction in her confidence that the memory of her erotic power will “follow [her lover] around,” which is a long way from the outright erotophobia of an early song such as “Fifteen.”

Photo by Mario Anzuoni/Reuters

On 1989, her erotic sophistication runneth over. On “Blank Space” she winks to her reputed “long list of ex-lovers,” cavalierly calls love “a game—want to play?” and seems altogether indifferent to her previously cherished notions of eternal soul mates, boasting, “I can make the bad guys good/ for a weekend.” The two lovers in “Style” mutually admit to cheating, which in an earlier Swift song would have been a cataclysm. And so on. There are of course many songs of romantic idealism, too, but the possessiveness of her previous songwriting persona seems to have been declared out of bounds.

Her timbres are polymorphous, too. Tossing aside the country imperative to keep vocals naturalistic, Swift uses studio processing—as well as her own expanding abilities—to try out all sorts of inflections: seductive whispers, joyful whoops, catty snarls, digitally flattened drawls that nearly squirm out of the grip of gender. She has a millennial’s complete comfort with technological extensions as expressive prostheses.

However, whether you consider it a sign of conservatism or feminist empowerment (and there’s no reason it can’t be both), she’s never explicit about acts and body parts, the way so much pop is in 2014. This is the woman who still won’t show her navel, which was to the white teen-pop of the 1980s, ’90s, and early 2000s what booty is to 2014: the lead instrument of every Top 40 starlet’s purported erotic self-assertion.

It’s not only that Swift comes from country—she also comes from upper-middle-class Pennsylvania suburbia. It’s easy to imagine that she took in Britney Spears and immediately thought “trashy.”

Photos by Christopher Polk/Getty Images for NARAS and Larry Busacca/Getty Images for NARAS

Her friendships with young feminists like Lorde, Rookie editor Tavi Gevinson, and Girls creator Lena Dunham are clearly, as she’s often said lately, broadening her concepts of female potential, including sexuality. But Swift’s sisterhood has its limits.

As Pretty Hate Machine

Part of the fun of 1989 is in watching Swift toy with boys, flipping the power dynamics of many of her early songs. As often as not, they’re the ones left longing and yearning, or used and tossed aside. I return to “Blank Space” here because it’s the real tone-setter for the record. It’s capped with a dominatrix declaration, delivered with a slippery mixture of clip and purr: “Boys only want love if it’s torture/ Don’t say I didn’t, say I didn’t warn ya.” Fair enough.

But when it comes to some other women, there’s a persistent feeling that another line in the song holds true: “Darling, I’m a nightmare dressed like a daydream.”

Her stylistic tributes, partnerships, and dedications signify her alliances. When she sings “I’m dancin’ on my own” in “Shake It Off,” I suspect that’s a salute to Robyn, a longtime Max Martin client whose ’80s-accented style could be taken as a general influence here. There are the nods to Heap, Lorde, Del Rey, and Dunham—bonus track “You Are in Love” depicts the growth of Dunham’s romance with boyfriend Jack Antonoff (of Fun and Bleachers, and of course Swift’s collaborator on “Out of the Woods” and “I Wish You Would”) with an untrammelled affection and admiration I find very moving.

But I take issue with Jon Caramanica’s claim in the New York Times that Swift is using “almost no contemporary references” on 1989 and competing with the rest of mainstream pop only by setting herself apart from it. Sure, she eschews hip-hop crossovers and other edgier gestures in her production, but the whole category of ’80s-ness has been a thing in white female pop for years now—and I think with that she puts herself in direct conscious competition with the likes of Katy Perry, Miley Cyrus, Lady Gaga, Charli XCX, Icona Pop, Iggy Azalea (is that a deliberate melodic grab from “Fancy” in “Bad Blood”?), and others, as a field of pretenders against whom to match both her persecution complex and her will to power.

I’m not taking too seriously the purported beef with Perry in the poison-pen letter “Bad Blood” (which I believe lampoons Perry’s own style)—that’s just more Swiftian stage management. But she does it with a chillingly vicious aplomb for an artist who in the past was so into positive thinking that she had her own line of greeting cards. Her recent banter about “brainless” and “evil pop” versus pop that is “clean and good and right” effects a curious conflation of morals and aesthetics I doubt she could coherently defend.

I’m not lecturing Swift that she should be a good girl and not scuffle with her rivals. All that friction is part of the joy of pop. But let’s not kid ourselves into thinking she’s not drawing up sides (and that those divisions don’t trace some sociologically telling, pre-existing outlines). Now that she’s officially in the pop fray, all those other divas are getting served: “If you come in my way/ just don’t.”

So you want to know what I think is really hidden under her high-waisted separates? A weapon. To borrow the title of an album released in 1989, a pretty hate machine. It probably looks a lot like that tesseract thingy from The Avengers.

Photo illustration by Slate. Photos by Christopher Polk/Getty Images for Clear Channel and courtesy of Marvel/IMDB.

As Feminist Hashtag

Because, on the other hand, you know, #gamergate. Maybe Swift’s “persecution complex” is merely realistic. #yesallwomen

As the Whitest Thing on Earth

We know Swift is gunning for other white-girl singers, then, but what about major pop stars of color, such as Rihanna, or, come on, Swift’s only real rival in pop domination and ubiquity in 2014, Beyoncé?

In short, Swift is too smart to set herself up against such hazardous targets. The performance idioms and genre conventions of R&B aren’t within her reach—which was of course the whole meaning of the “Shake It Off” video, a pre-emptive admission that there are parts of the pop game Tay cannot play, with the vital area of dancing No. 1 on that list. She can’t do it and, the video insists, she doesn’t mind. She’s an auteur, not a showgirl.

I’d venture to defend the twerking scene that briefly landed Swift in perdition as entirely a satirical shot across Miley Cyrus’ bow (“can’t stop, won’t stop movin’,” Swift taunts) that ended up backfiring in large part due to bad timing. As Ann Powers has pointed out, the video was released at the height of the police violence crisis in Ferguson, Missouri, in August, which heightened sensitivities considerably.

Swift also can’t compete vocally with the likes of Beyoncé, and again doesn’t aim to try. In fact I think she fears what it might entail to try. So she hires a teen-pop veteran such as Martin rather than a DJ Mustard or a Mike Will Made It, as Caramanica notes. The “Shake It Off” video kerfuffle probably made her feel that was a good call.

But accusing Swift, as John Herrman did on the Awl, of being “skeptical of America’s demographic progress” is several leaps too far. I wouldn’t disagree that Swift’s style in many ways is one of “intentional performed whiteness,” as Herrman wrote—she would regard that as being authentic to herself. And there are times where she’s used that privileged veneer of innocence as a shield—for instance, acting the awkward underdog when she’s really the mean girl—making “nightmare dressed up as a daydream” refreshingly frank.

Like most white artists, and most white people, Swift could dig far deeper into her position. But if she’s damned if she does flirt with cross-cultural appropriation, and damned if she doesn’t, well, I don’t know about you, but I’m feeling a catch-22. And she doesn’t deserve that, or at least no more than the mostly middle-class white critics sniping at her do. If only there were a rhythmic chant somewhere on this album we could direct at them.

As Apparition of the Madonna

A “nightmare dressed like a daydream”—but what kind of nightmare? Given 1989’s title, perhaps it is Stephen Dedalus’ nightmare: history, from which he is trying to awake. Perhaps it is the actual history of 1989—the year, after all, of the fall of the Berlin Wall and the showdown in Tiananmen Square, the year of the “End of History,” the twilight of the Cold War, the dawn of neoliberal triumphalism. The year of “Like a Prayer.”

When Taylor Swift talks about 1989 as an ’80s album, what she is really trying to do, I would argue, is nominate herself as the new Madonna—the multiple-threat female performer defined by her command of both destiny and zeitgeist. She’s a business, man. In the very act of switching genres, she’s emulating Madonna’s mutability, her multiple opportunistic identities. Again, like Madonna, she’s hinting, “Taylor Swift” is in many ways both corporation and constructed character.

(If only Swift would take this further, to David Bowie–like extremes—if 1989 is, say, her Young Americans, then maybe next we’ll get her Low or her Scary Monsters? OK, in my wildest dreams.)

Photos by Colleen Combes/Reuters and Mark Davis/Getty Images

I’ve mentioned that the ’80s-ness of 1989 has been aggrandized, but wherever it is true the sound tends to be aiming for (and not quite reaching) Madonna. “Style” gets tagged as sounding like Don Henley or Miami Vice, but you could just as easily say “Into the Groove.”

And if not Madonna, then it’s the proto-Madonna, her more vulnerable forerunner, Cyndi Lauper. 1989 track 10, “How You Get the Girl,” for instance, should be the closing theme for a John Hughes movie starring Molly Ringwald giving Cyndi Lauper a makeover. It’s immediately followed by “This Love,” which is “True Colors” making out with Amy Grant (aka How You Get Celine Dion).

As the Omphalos of Capital

The year 1989 also saw the earliest hits of New Kids on the Block, who would go on to define the 1990s boy-band genre, out of which came teen pop, Robyn, Max Martin, and ultimately 1989.

Joshua Clover, in his 2009 book 1989: Bob Dylan Didn’t Have This to Sing About, examines how the historical events of “the long 1989” were culturally mulched in the pop music of the era. Clover’s subtitle is a kind of mind-blowing line from Jesus Jones’ “Right Here, Right Now,” that 1991 hit about “watching the world wake up from history.”

Clover argues that the period was a high-water mark for pop music because the “deracinated timelessness” that pop always aims at was perfectly matched by the illusion of universal consensus at the end of the Cold War, which drove pop to “attempt to know itself as excess, as a superfluity which exceeds every container … in the face of which meaningful action is impossible.”

This 1989 meta-pop awareness is also in the makeup of 1989, in the sense that it is meta-Taylor, an album difficult to hear as music as much as career maneuver, with her personal life as a kind of sub-metafiction within that career. In this sense 1989 is about making hits about hits, money out of money—about compounding interest and deriving derivatives.

Swift’s move to Tribeca, to a post-Bloomberg Manhattan thoroughly colonized by high finance, is in fact a kind of homecoming, as she grew up the daughter of a third-generation high-level stock broker, a Merrill Lynch vice president living in this cavernous three-story house in Wyomissing, Pennsylvania.

During an interview on the Canadian country cable network CMT on Monday night, I watched her lose her temper on her dad’s behalf when host Paul McGuire quoted country star Jason Aldean telling Billboard, “I can’t sing you a song about being a stockbroker on Wall Street, because I don’t even know where the hell Wall Street’s at.” Though Swift should know perfectly well why a Nashville country star might stretch the down-home truth on that count, she seemed genuinely taken aback that anyone would deny knowing where Wall Street is. He might as well have denied Jesus, or Disneyland.

It reminded me of omphalos syndrome, named from the Greek word for “navel.” It is the delusion that whatever locale you regard as the seat of power is, as author Cullen Murphy puts it, “the focal point of reality—that nothing is more important than what happens there, and that no ideas or perceptions are more important than those of its elites.” It was first diagnosed of Imperial Rome.

Welcome to New York, the imperial omphalos of global capital. It’s been waiting for you.

Clover writes that in the music of the post-1989 era we must also hear “empire singing … the ambiguous exultation of America’s geopolitical belle époque, the seeming restoration of its glory as global hegemon … the antechamber of the unipolar world, of the Washington Consensus and the last Pax Americana, which contains within it the spectacle of the nineties economic boom.”

Sometimes when I’m enjoying Taylor Swift, I suddenly feel with a shiver that I’m hearing Wall Street singing—disguised as an everygirl dressed like a daydream. Let the choir sing.

Dolly Parton didn’t have this to sing about.

And Finally, as Gordian Knot

Among quite a few contenders, my favorite song on 1989 is the same as most people’s, “Out of the Woods,” to which Antonoff’s music contributes an eccentric grandeur that nothing else on the record can match. It has Swift’s vaunted eye for detail but also this quivering, unquellable tension.

So many of the songs on this album use a repeated phrase for the chorus, but on “Out of the Woods,” there’s a unity of content and form, as the protagonist is asking herself whether this relationship has a prayer, and the obsessive-compulsive way she reiterates the question, worries at the rope, should be her answer: “Good!” she lies.

It’s the same way I’ve been chasing Swift’s geist in circles, like a vinyl 45 (a format that came to its commercial end in 1989) making its eternal revolutions around that empty whatchamacallit at its center. You could tug forever at the ends of Swift’s elusive, invisible abdominal bundle of avarice and sentiment, art, ego, envy, love and hate, drought and flood, truth and fiction, savior and monster—and it would never come undone.

Legend knows only one answer to such an impossible knot. You have to rent it in two, cut the cord. Yet who will step up to the challenge and act the Alexander to this pop-cultural oxcart? Who can wield the cleansing blade? In sooth, it must be the fellow over there …

… with the hella good hair. Come on over, baby.

*Correction, Oct. 30, 2014: This article originally misstated the title of the song “New Romantics” as “New Romance.”