The Time Is Out of Joint

Behind the scenes on D'Angelo's Voodoo.

The following essay is a series of excerpts from Jason King’s liner notes for Light in the Attic’s new vinyl reissue of D’Angelo’s seminal 2000 album Voodoo.

Holdups and false starts kept Voodoo from a '90s release. Perfectionist D’Angelo had become distracted by weed and weightlifting, and debilitated by sophomore pressure to follow up his groundbreaking 1995 debut Brown Sugar. In the interim he’d fathered two children, switched managers, jumped to a new record label, and made cameos on scattershot soundtracks. Two promo singles dropped: murky, sample-heavy “Devil's Pie” in October 1998 and Redman/Method Man-assisted toe-tapper “Left and Right” a year later. But promises of a full-length studio album evaporated into the ether. Voodoo might have seen its commercial release in November 1999, but a planned duet with Lauryn Hill on a lurching cover of Roberta Flack's 1975 “Feel Like Making Love” remained unfinished and the album was pushed back until just after the New Year. (The rendition would ultimately wind up on Voodoo as a solo D'Angelo record without Hill.)

Voodoo was a project obsessed with 1960s, '70s, and '80s funk and soul—a nostalgic nod to the ideas and inventions of black music trailblazers like Jimi Hendrix, Sly Stone, George Clinton, Kool and the Gang, Al Green, and Prince, powered by avant-garde hip-hop-influenced rhythms. As such, Voodoo is decidedly postmodern, bopping in and out of and between eras without necessarily belonging to any singular era in particular. And perhaps the delayed, dislocated timing of Voodoo’s commercial release suggests a truism about D'Angelo himself: Wherever he seems to go, the time is, as Hamlet once said, out of joint.

Brown Sugar relied on programming, with many of the songs pre-written and arranged before D’Angelo recorded them. Voodoo, on the other hand, was a more organic, improvisatory, and experimental affair. Much of the songwriting occurred in the studio. The innovation kicked off, it seems, with Jimi Hendrix. In a recent interview, Voodoo's mix engineer Russ Elevado recounted to me how he helped turn D'Angelo onto Hendrix in the mid '90s. "All D'Angelo had heard of Jimi at that time were songs like Purple Haze and albums like Are You Experienced," he said. "I had been hired to mix a few songs on Brown Sugar; and, around '94 or '95, I kept trying to play Jimi for D'Angelo but at the time he wasn’t really open to it. Finally when I went down to Virginia to talk about the concept for what was to become Voodoo, D'Angelo and I went out for breakfast, and in the car I popped in Electric Ladyland. He looked at me as if to say: ‘Who is this?’"

No surprise, then, that they chose downtown New York's Electric Lady, the famed studio Hendrix built before he died, as the venue for recording the album. "There we were,” Elevado recalls, “blowing the dust off the original Rhodes that Stevie supposedly recorded with in the early 1970s, and blowing dust off some of the microphones. You have to remember that at that time in the mid 1990s, hardly anybody in soul music was doing any recordings with vintage equipment like that.”

The concept behind Voodoo was simple. Put together a kick-ass ensemble of R&B musicians bent on grooving together. Record them live, in real time, jamming face-to-face in an effort to capture their conviviality and chemistry. This was the way funk records used to be made in the pre-digital era when people who knew what they were doing were actually making them. For Voodoo's core rhythm trio, D'Angelo recruited his friend and colleague, the Roots' Afroed visionary Ahmir "Questlove" Thompson to play drums, and Welsh journeyman Pino Palladino to hold down the bass. Additional collaborators included guitar mavens Charlie Hunter, Spanky Alford and Mike Campbell, neo-soul stalwart James Poyser on keys, and jazz prodigy Roy Hargrove on horns.

“I was a kind of a walking YouTube before YouTube existed,” said Questlove in our recent interview. “People felt comfortable to share archives with me and trusted that I wouldn’t go out and exploit them. So I would get what I would call ‘treats:’ you know, an old promoter that might have worked for Bill Graham back in the day … would hand me a manila envelope and it would be, say, a rare copy of Sly and the Family Stone’s four shows at the Fillmore. I’d take it back to Electric Lady Studios and make copies of it and we’d just study it and then a week later we’d start working on it. That was the process.” The band spent all of 1996 and most of 1997, he says, “just watching treats and jamming. I have to say we really hit our stride in late 1997 when I went to Japan and unearthed about 4,000 video episodes of Soul Train. Then we really got down to business and started recording the album.”

"When my musician friends first heard the album, they were confused,” notes Pino Palladino. “They thought: It sounds kinda weird, the timing’s kinda weird on it. D'Angelo explained the concept of how he wanted the bass to sound to me before we started playing. I attempted to put the bassline where I thought he wanted it. I would never have thought of putting it so far back behind the beat. But it becomes a different feeling: It stretches in and out of different accents."

The heavy backphrasing is what D’Angelo collaborator Raphael Saadiq once referred to as performing with "the grease," in the effort to achieve a "loose, way back in the pocket feel" or a "rubber band feeling." The backphrasing means that the bass is constantly changing its location in relation to Questlove’s straight-ahead, heavy time, impeccable drumming. The effect is a jumpy, unsettling pulse. The bass seems out of joint, never quite landing where you'd expect. Pino theorizes that D'Angelo likely takes his clues from hip-hop. He explains: "Hip-hop is music that’s been deconstructed, it's made up of bits of samples arranged in different places and often placed behind the beat. The way people sampled stuff influenced D in terms of the way he would write his music. When I first heard the backing tracks for Voodoo, it struck me as the kind of thing J Dilla would do, how he would deconstruct and reconstruct rhythms and just kinda deliberately mess things up. So you get these messed-up wobbly rhythms. You know, Dilla might take a four-chord pattern and start it on the second chord. D does that kinda thing too in his writing.”

Questlove echoes his colleagues when he discusses his drumming on Voodoo. “The thing that really attracted me to D’Angelo’s music was this inebriated execution thing that he had, which we both got from J Dilla. Dilla would program his drums non-quantized: in layman’s speak, it’s the equivalent of having a 5-year old play drums. It sounds sloppy, but there’s a human quality there. Playing drums the way I did for the Voodoo sessions was necessary for me because I had been playing differently before we started recording. There was a time in the 1990s where there was resistance to the Roots’ presentation: There were hip-hoppers who felt like we were doing a disservice to the culture because we weren’t real enough for the street. In a culture of samples, I had been told I sound too much like a drummer. So prior to Voodoo, I had been going through a period where I felt I had to prove to people that I was a machine: I had decided that my playing was going to be cold, you wouldn’t be able to tell if I was a sample or not. I spent three years of just icing my presentation to a science where I was just a kind of super-metronome; I spent three years of trying to hide myself. Then, in walks D’Angelo, and he basically tells me: ‘Yo, I need you to strip yourself of all that coldness and play human. I need you to play fucked up!’ He wanted me to play as drunk and as slow and as dusted as I’ve ever played in my life. I don’t smoke or drink, so he really guided me to a level of creativity I wouldn’t normally reach without some sort of stimulant. The first year of recording he would say: ‘I need you to keep the pocket but don’t drag behind me, but play a little crooked,’ if that makes any sense whatsoever.”

Most of the songs on Voodoo are six minutes or more (lengthy for pop) and almost all the intoxicating, druggy tempos (with the exception of the driving "Spanish Joint") check in far below 100 beats per minute. Those molasses tempos are extremely unusual for commercial R&B, which often clocks in at 120 bpm or higher. The resulting feeling on Voodoo is chilled out, unhurried. It’s an album that takes its sweet time. Rolling Stone critic James Hunter once deftly described the sound of Voodoo as “loose grooves and lazy-smoke,” calling it ”soul music that moves like smoke easing from a blunt.”

Some fans couldn’t quite get into the songwriting on Voodoo. Or maybe they got bored by its sleepiness. Many, however, managed to rediscover the album’s songs attending the Voodoo World Tour. His tour manager at the time, Alan Leeds, recalls that that D'Angelo is an incredibly generous performer. "He wants the musicians to get him off. He comes to the stage for that. As opposed to just coming for the audience, he actually comes for the musicians to get him off."

And let's face it: One of the main reasons certain fans came to see D'Angelo was to hear (and see) him perform Voodoo's only real hit single, "Untitled (How Does it Feel).” Co-written by Raphael Saadiq, "Untitled" is a slow-burn ballad that borrows chord progressions and production ideas from 1980s Prince ballads —to my ears, it sounds like a lost track that might have been written sometime between 1981's "Do Me Baby" and 1987's "Adore." Given its appearance on an album full of deliberately unfocused and unhurried grooves, Alan Leeds refers to "Untitled" as "the album's anomaly,” “a fastball down the middle,” “an easily accessible track with the radio hook.”

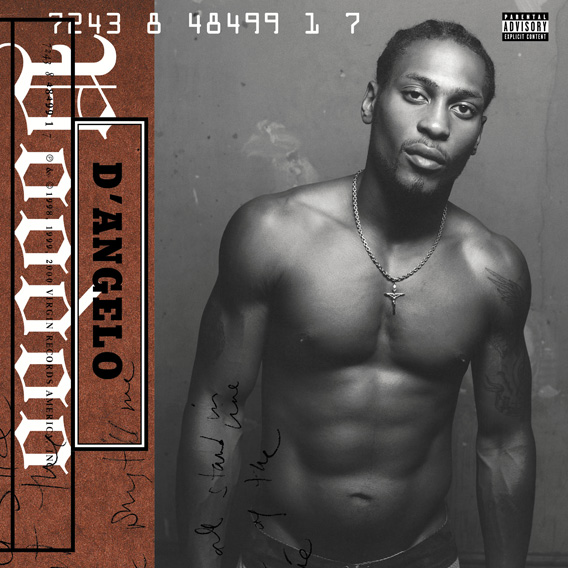

But it was the high-concept, simple-execution music video for "Untitled"—in which a shirtless D'Angelo, filmed from just below the waist up, sings to the camera, getting who knows what done to him by an unseen partner—that sent audiences, especially women and gay men, rushing to see D'Angelo live and to purchase the album. The subject of academic articles and endless on- and offline discussions, the “Untitled” video has become so iconic in terms of the history of black male sexual representation that it's almost impossible to think about the song as an independent entity outside of its visual marketing. The video did its job: it drove sales for both the song and the album (and the tour); “Untitled” ultimately rose to No. 2 on the R&B charts.

But if "Untitled" was the key to Voodoo's success, it was also the key to D'Angelo's ultimate unraveling. Part of the problem was that he'd become recognized in the culture as more of a bachelor stud than a serious musician, and his recognition of that misplaced respect may have been deleterious to his confidence and psychological health. Alan Leeds recalls the first series of shows of the Voodoo tour in which "girls in the audience were shouting ‘take it off!’. The look on D’s face—I don’t even know how to describe. He was stunned. There was a certain percentage of our audience thinking it was Chippendales. I don’t think he thought it through to think how the video was going to come back at him when he got on the stage." When an artist becomes reduced solely to the terms of his or her body, it can stifle a career, or even foreclose it altogether. What makes the story worse is that D'Angelo had willfully participated in his own exploitation.

With the exception of a few scattered musical collaborations here and there, D'Angelo entered into a long exile from the music industry. For some, D’Angelo became more known for his appearance on tabloid websites than for his music: over the years we’d hear about him drunk, on drugs, in rehab, in label turmoil, in a near-fatal car accident, arrested for soliciting an undercover female cop for sex. Our Internet searches would be haunted by a 2005 Virginia mugshot in which D’Angelo looked flat and bloated: the exact inverse of his Voodoo image. Oh, how he’d come undone.

And so, in retrospect, Voodoo is something of cautionary tale, another chapter in the depressing story of black male soul geniuses whose careers descend into dysfunction. For all of Voodoo's claims to realness and authenticity, D'Angelo's imaging, while rooted in promise, had been in some ways a charade, an unsustainable performance of black masculinity gone awry. D’Angelo would not tour again until 2012, when he returned to the stage in support of an album project that is still in the works.

Another way to look at D'Angelo's career trajectory is that he has always marched to the beat of his own metronome. With the exception of maybe Terrence Malick, no other celebrity of the 1990s or 2000s has fucked with time, and the expectations around time, as much D'Angelo—both in the music and in his career as a whole. He takes his own sweet time. We can name tons of celebrities who seem to be running faster than the speed of light, multitasking and oversharing in a sometimes desperate effort to stay afloat in the marketplace. D'Angelo, on the other hand, is a hermit and a chronic undersharer. He rarely does interviews unless he's got a product to hawk, he doesn't have a fashion line and businesses on the side, he doesn't appear on infomercials, he doesn't do films and he doesn't have a TV sitcom in the works. D'Angelo is simply a musician to his core. And that's enough. For reasons that have clearly not always been under his control, D'Angelo's entire career suggests an alternate narrative to the need for speed and immediacy and high visibility that is pop culture in the age of the Internet. Nope, D’Angelo just does his own thang.

Jason King’s complete liner notes are available on Light in the Attic’s new vinyl reissue of Voodoo.