Kind of Blue

Why the best-selling jazz album of all time is so great.

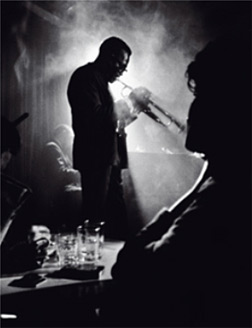

Miles Davis'Kind of Blue, which was released 50 years ago today, is a nearly unique thing in music or any other creative realm: a huge hit—the best-selling jazz album of all time— and the spearhead of an artistic revolution. Everyone, even people who say they don't like jazz, likes Kind of Blue. It's cool, romantic, melancholic, and gorgeously melodic. But why do critics regard it as one of the best jazz albums ever made? What is it about Kind of Blue that makes it not just pleasant but important? On March 2, 1959, when its first tracks were laid down at Columbia Records' 30th Street Studio (the album would be released on Aug. 17), Charlie Parker, the exemplar of modern jazz, the greatest alto saxophonist ever, had been dead for four years, almost to the day. The jazz world was still waiting, longing, for "the next Charlie Parker" and wondering where he'd take the music. Parker and his trumpeter sidekick, Dizzy Gillespie—Bird and Diz, as they were called—had launched the jazz revolution of the 1940s, known as bebop. Their concept was to take a standard blues or ballad and to improvise a whole new melody built on its chord changes. This in itself was nothing new. But they took it to a new level, extending the chords to more intricate patterns, playing them in darting, syncopated phrases, usually at breakneck tempos. The problem was, Parker not only invented bebop, he perfected it. There were only so many chords you could lay down in a 12-bar blues or a 32-bar song, only so many variations you could play on those chords. By the time he died, even Parker was running out of steam.

When Miles Davis came to New York in 1945, at the age of 19, he replaced Gillespie as Parker's trumpeter for a few years and played very much in their style. A decade later, he, too, was wondering what to do next.

The answer came from a friend of his named George Russell (who died just last month at the age of 86). A brilliant composer and scholar in his own right, Russell spent the better part of the '50s devising a new theory of jazz improvisation based not on chord changes but on scales or "modes." The kind of music that resulted was often called "modal" jazz. (A scale consists of the eight notes from one octave to the next. * A chord consists of three or four specific notes in that scale, played together or in sequence: For instance, a C chord is C-E-G.)

This distinction may seem slight, but its implications were enormous. In a bebop improvisation, the chord changes (which occur when, usually, the pianist changes the harmony from one chord to another) serve as a compass; they point the direction to the next bar or the next phrase. Chords follow a particular pattern (that's why it's easy to hum along with most blues and ballads); you know what the next chord will be; you know that the notes you play will consist of the notes that comprise that chord or some variation on them. Playing blues, you know that the sequence of chord changes will be finished in 12 bars (or, if it's a song, 32 bars), and then you'll either end your solo or start the sequence again.

Russell threw the compass out the window. You could play all the notes of a scale, which is to say any and all notes. "It is for the musician to sing his own song really," Russell wrote, "without having to meet the deadline of a particular chord." In other words, he continued, "you are free to do anything" (the italics were his), "as long as you know where home is"—as long as you know where you're going to wind up.

One night in 1958, Russell sat down with Davis at a piano and laid out his theory's possibilities—how to link chords, scales, and melodies in almost unlimited combinations. Miles realized this was a way out of bebop's cul-de-sac. "Man," he told Russell, "if Bird was alive, this would kill him."

In an interview that year with critic Nat Hentoff, Miles explained the new approach. "When you go this way," he said, "you can go on forever. You don't have to worry about changes, and you can do more with time. It becomes a challenge to see how melodically inventive you are. … I think a movement in jazz is beginning, away from the conventional string of chords and a return to emphasis on melodic rather than harmonic variations. There will be fewer chords but infinite possibilities as to what to do with them."

Davis needed one more thing before he could go this route: a pianist who knew how to accompany without playing chords. This was a radical notion. Laying down the chords—supplying the frontline horn players with the compass that kept their improvisations on the right path—was what modern jazz pianists did. Russell recommended someone he'd hired for a few of his own sessions, an intense young white man named Bill Evans.

Evans was conservatory-trained with a penchant for the French Impressionist composers, like Ravel and Debussy, whose harmonies floated airily above the melody line. When Evans started playing jazz, he tended not to play the root of a chord; for instance, when playing a C chord, he'd avoid playing a C note. Instead, he'd play some other note in, or hovering around, the chord, suggesting the chord without locking himself into its restraints.

Davis hired Evans for his next recording date, the session that became Kind of Blue, which would be the perfect expression of this new approach to playing.

The clearest example of its novelty is a piece, composed (without credit) by Evans, called "Flamenco Sketches." At most jazz sessions, the sheet music that the leader passes around to the band consists of "heads"—the first 12 or so bars of a tune, with the chords notated above. The band plays the head, then each player improvises on the chords. But for "Flamenco Sketches," Evans had jotted down the notes of five scales, each of which expressed a slightly different mood. At the top of the sheet, he wrote, "Play in the sound of these scales."

For the band's two saxophone players, John Coltrane on tenor and Julian "Cannonball" Adderley on alto, it was a particularly bizarre instruction. Both were astonishingly adept improvisers, but they built their creations strictly on chords, Adderley as an acolyte of Charlie Parker (with a gospel-infused tone), Coltrane as an almost spiritual explorer, searching for the right sound, the right note, mapping out his voyage on charts of chords, piling and inverting chords on top of chords, expanding each note of a chord to a new chord, not knowing which combinations might work and therefore trying them all.

A few months after the Kind of Blue sessions, Coltrane led his own band on an album called Giant Steps, which pressed this quest to its ultimate degree—literally:

Giant Steps marked the end of the bebop frontier; Coltrane knew this, and, afterward, would go in a whole new direction, less tethered to structure, more "free," than even Russell's concept envisioned. But on Kind of Blue, especially "Flamenco Sketches," he took his first—and most lyrical—step out on that brink:

The departure from bebop is clear from the album's opening tune, "So What," which would emerge as this new sound's anthem. Evans describes it on the album's liner notes as "a simple figure based on 16 measures of one scale, 8 of another and 8 more of the first … in free rhythmic style." (Loose as it is, this was more structured than some of the pieces. Evans writes that, for "Flamenco Sketches," the improvisations on each scale can last "as long as the soloist wishes.") In this 30-second clip from "So What," Davis improvises on a single scale for all but the last few seconds, when Evans signals a shift to a different scale:

Compare this with "Freddie Freeloader," the album's only conventional blues. (For this track alone, Miles let his usual pianist, Wynton Kelly, a straight blues-and-bebop keyboardist, sit in for Evans):

Structurally, it's similar to the early bebop tunes that Davis played with Parker in the mid-1940s, the melody latched to the pianist's chord changes, which occur nearly every bar, as in this 1946 Parker recording of "Ornithology" with Davis as sideman:

Now contrast these conventional bop pieces with the most fully developed piece of "modal" jazz" on Kind of Blue, called "All Blues":

It has the same feel as the other blues tunes, but listen closely: The horns, blowing harmony in the background, are playing the same notes in each bar; they're not shifting them to follow the chord changes; there are no chord changes. It sounds (hence the album's title) kind of blue.

So Kind of Blue sounded different from the jazz that came before it. But what made it so great? The answer here is simple: the musicians. Throughout his career, certainly through the 1950s and '60s, Miles Davis was an instinctively brilliant recruiter; a large percentage of his sidemen went on to be great leaders, and these sidemen—especially Evans, Coltrane, and Adderley—were among his greatest. They came to the date, were handed music that allowed them unprecedented freedom (to sing their "own song," as Russell put it), and they lived up to the challenge, usually on the first take; they had a lot of their own song to sing.

The album's legacy is mixed, precisely for this reason. It opened up a whole new path of freedom to jazz musicians: Those who had something to say thrived; those who didn't, noodled. That's the dark side of what Miles Davis and George Russell (and, a few months later, Ornette Coleman, in his own even-freer style of jazz) wrought: a lot of noodling—New Age noodling, jazz-rock-fusion noodling, blaring-and-squealing noodling—all of it baleful, boring, and deadly (literally deadly, given the rise of tight and riveting rock 'n' roll). Some of their successors confused freedom with just blowing whatever came into their heads, and it turned out there wasn't much there.

Another appealing thing about Kind of Blue, though it's also a heartbreaking thing: There was no sequel. Soon after the recording date, the band broke up. Evans formed his own piano trio; Adderley went back to playing gospel-tinged bop; Coltrane (after making Giant Steps) took his own road to freedom; Davis, too, retreated to earlier forms for the next few years, until he formed his next great band, in the mid-'60s, with younger musicians who pushed him on to more adventurous experiments.

Kind of Blue is a one-shot deal, so dreamily perfect you can hardly believe someone created it. Which is why it remains so deeply satisfying, on whatever level you experience it, as moody background music or as the center of your existence. Listen to it 100 times or so, and you still marvel at its spontaneous inventions; now and then, you'll even hear something new.

Correction, Aug. 19, 2009: The article originally stated that a scale consists of 12 notes, which is true for chromatic scales (scales with all the notes—natural, flat, and sharp), but since Russell was talking about scales or "modes" that sound different from one another (meaning they include at least some different notes), this can be true only of scales with eight tones or eight notes. ( Return to the corrected sentence.)