Arts has moved! You can find new stories here.

Longform’s Best Culture Writing of 2013

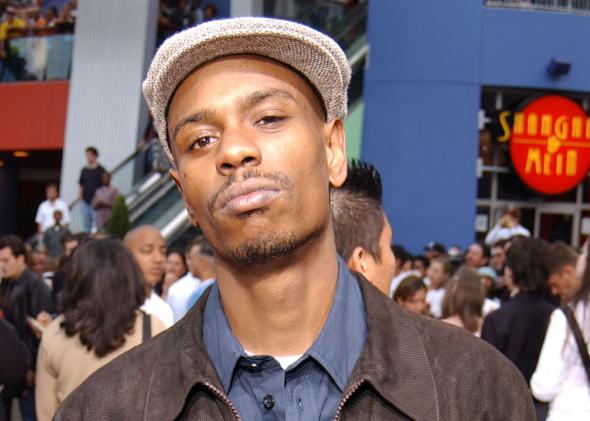

Dave Chappelle, Miley Cyrus, and the best book of the year.

Photo by Robert Mora/Getty Images

This week on Slate, we’ll be sharing our favorite articles of the year. For our full list—including the top 10 of the year, plus picks in sports, politics, tech, and more—check out Longform’s Best of 2013.

Searching for Dave Chappelle 10 years after he left his show.

When news of his decision to cease filming the third season of the show first made headlines, there were many spectacular rumors. He had quit the show without any warning. He had unceremoniously ditched its cocreator, his good friend Neal Brennan, leaving him stranded. Chappelle was now addicted to crack. He had lost his mind. The most insane speculation I saw was posted on a friend’s Facebook page at 3 a.m. A website had alleged that a powerful cabal of black leaders—Oprah Winfrey, Bill Cosby, and others—were so offended by Chappelle’s use of the n-word that they had him intimidated and banned. The controversial “Niggar Family” sketch, where viewers were introduced to an Ozzie and Harriet–like 1950s suburban, white, upper-class family named “the Niggars,” was said to have set them off. The weirdest thing was that people actually went for such stories. Chappelle’s brief moment in television had been that incendiary. It didn’t matter that Chappelle himself had told Oprah on national television that he had quit wholly of his own accord.

Advertisement

A few days in the life of Miley Cyrus.

In the backroom of a tattoo parlor on North La Brea Avenue in L.A., Miley Cyrus is about to get some new ink. "All right, face down," says the tattoo artist, a bald guy named Mojo. Miley flips onto her stomach and sticks her ass in the air. On the bottom of her dirty feet, in ballpoint pen, are written the words ROLLING (right foot) and $TONE (left).

George Saunders Has Written the Best Book You’ll Read This Year

Joel Lovell • New York Times Magazine

Advertisement

An ode to Saunders.

Aside from all the formal invention and satirical energy of Saunders’s fiction, the main thing about it, which tends not to get its due, is how much it makes you feel. I’ve loved Saunders’s work for years and spent a lot of hours with him over the past few months trying to understand how he’s able to do what he does, but it has been a real struggle to find an accurate way to express my emotional response to his stories. One thing is that you read them and you feel known, if that makes any sense. Or, possibly even woollier, you feel as if he understands humanity in a way that no one else quite does, and you’re comforted by it. Even if that comfort often comes in very strange packages, like say, a story in which a once-chaste aunt comes back from the dead to encourage her nephew, who works at a male-stripper restaurant (sort of like Hooters, except with guys, and sleazier), to start unzipping and showing his wares to the patrons, so he can make extra tips and help his family avert a tragic future that she has foretold.

A visit to Star Axis, a desert art installation that connects you to the cosmos.

As I moved further up the staircase, the circular frame around Polaris dilated, taking me into past and future skies simultaneously. I thought about how the human relationship to the sky had changed during this last cycle of precession. I wondered what the night sky looked like to people of prehistoric times. How had its darkness and points of light appeared, as filtered through their beliefs and mythologies? We know the sky has always had a profound effect on the human mind, partly because it has always been a source of physical danger. Ever since our days on the savannah, the sky has menaced us with sunburn and thirst, and storms that pour out of its clouds without warning. It has also sent explosives to the Earth’s surface, in the form of comets and asteroids, and inflicted blindness, on those who dare stare into the retina-ruining sun. But it is not these hazards that give the sky its most potent psychological power over us. We tremble before the sky for deeper, more philosophical reasons. We fear it because, more than any other natural phenomenon, the sky offers us a direct experience of the unknown.

On photographer Garry Winogrand and the unedited archive of more than 500,000 exposures he left behind.

Garry Winogrand used to say that he took photographs of things to see what they would look like as photographs. He took a lot of them. He photographed relentlessly: crowds, zoos, dogs, cars, parties, sidewalks, train stations and women, always more women. He'd describe a good night as "thirty-five rolls." A good year might involve a thousand. He was always slow about editing. He had a rule that he wouldn't even look at an exposure for a year, so that emotion wouldn't cloud his judgment, but towards the end of his life he wasn't even doing that anymore. He just let his rolls pile up in trash cans and in the fridge.

For more of the year’s great writing, check out Longform’s Best of 2013.