The Murders of Gonzago

How did we forget the mass killings in Indonesia? And what might they have taught us about Vietnam?

Photo courtesy of Drafthouse Films

The play’s the thing, wherein I’ll catch the conscience of the King.

— Hamlet, Act 3, Scene 2

1. Foul Deeds Will Rise

Is it possible to kill 1 million people and then forget about it? Or if it has been erased from consciousness, is there an unconscious residue, a stain that remains?

Josh Oppenheimer’s film The Act of Killing—for which I served, along with Werner Herzog, as an executive producer—is an examination of the Indonesian mass killings of 1965-66, in which between 500,000 and 1 million people died.1 The Act of Killing is truly unlike any other documentary film. A good thing in my opinion. One of the extraordinary things about documentary is that you get to continually reinvent the form, reinvent what it means to make a documentary—and Oppenheimer did just that. He identified several of the killers from 1965 and convinced them to make a movie about the killings. But the film is even weirder than that. Oppenheimer convinced these killers to act in a movie about the making of a movie about the killings. There would be re-enactments of the murders by the actual perpetrators. There would be singing, and there would be dancing. A perverted hall of mirrors.

But there is method to Oppenheimer’s madness—the idea that by re-enacting the murders, he, the viewers of the movie, and the various perpetrators recruited to participate could become reconnected to a history that had nearly vanished into a crepuscular past. Oppenheimer has the optimistic thought that the past is inside us and can be brought back to life.

As the killings of the mid-1960s spread across Indonesia, Sukarno, Indonesia’s left-leaning first president since its 1949 independence, was marginalized and eventually replaced in 1967 with Suharto, a general in the army. Almost immediately, the Suharto regime sought to hide the history of what happened. The killers were neither brought to justice nor given reason to believe that they had done anything wrong.

On the contrary, they became heroes of the new order. Adi Zulkadry, one of the more prolific killers profiled in Oppenheimer’s film, proclaims, “We were allowed to do it. And the proof is, we murdered people and were never punished. The people we killed—there’s nothing to be done about it. They have to accept it. Maybe I’m just trying to make myself feel better, but it works. I’ve never felt guilty, never been depressed, never had nightmares.”

The Act of Killing opens with a musical interlude and then an introduction. The basic background information appears over a scene in Medan—against a background of revolving billboards for flavored syrups (Pohon Pinang), high rises, and a truck-ramp used by skateboarders:

“In 1965, the Indonesian government was overthrown by the military.

Anybody opposed to the military dictatorship could be accused of being a communist: union members, landless farmers, intellectuals, and the ethnic Chinese. In less than a year, and with the direct aid of Western governments, over 1 million ‘communists’ were murdered. The army used paramilitaries and gangsters to carry out the killings. These men have been in power—and have persecuted their opponents—ever since.

When we met the killers, they proudly told us stories about what they did. To understand why, we asked them to create scenes about the killings in whatever ways they wished. This film follows that process, and documents its consequences.”

* * *

The film’s central character is Anwar Congo. (I hesitate to call him the protagonist.) In 1965, he had been the leader of a death squad in Medan, an Indonesian city of some 4 million people. Tall, thin, cadaverous, hidden behind dark glasses with an assortment of wide-lapelled suits—lime green, canary yellow. Congo seems as if on display, flamboyant to no particular purpose. He tells Oppenheimer about his love of the movies, particularly the Hollywood epics of the 1950s. Cecil B. DeMille’s Samson and Delilah and The Ten Commandments. Movies were part of the deal from the beginning.

Photo courtesy of Paramount Pictures

As Congo explains:

“If we watched a happy film, like an Elvis movie, we’d walk out of the cinema with a smile, dancing along to the music. Our hands and feet, still dancing—still in the mood of the film—and if girls passed, we’d whistle. We were excited. We didn’t care what people thought. This was the paramilitary office, where I always killed people. I’d see the person being interrogated … I wouldn’t be sadistic. I’d give the guy a cigarette … It was like we were killing happily.”

No knives. No guns. His basic tools were a chair, piano wire, a stick. Wrap the wire around the victim’s neck. Pull, then twist. An improvised garrote. Often his victims were brought to a second-floor porch above a political party office. (It is now a store that sells handbags and other accessories). He tells stories about how they pled for their lives, how the bodies were put in burlap sacks and dumped in the river. All told dispassionately—as though he’s describing a family picnic.

“There’s many ghosts here, because many people were killed here … They died unnatural deaths. They arrived perfectly healthy. When they got here they were beaten up and died … Dragged around ... And dumped ... At first we beat them to death. But there was too much blood. There was so much blood here ... So when we cleaned it up, it smelled awful. To avoid the blood, I used this system. Can I show you ...?”

2. This Distracted Globe

The finished film was shown for the first time at the Telluride Film Festival. After the screening, I got into an argument with a critic who told me that he knew less about the Indonesian genocide after seeing the film than he did before—that the film provided insufficient background information and little historical context. Hard to argue. The critic was right. But I believe he misunderstood what Oppenheimer was trying to do.2 Oppenheimer is not offering a historical account of what happened in Indonesia, but rather an examination of the nature of memory and of history.

I called Oppenheimer in Copenhagen.

Errol Morris: Would you call this a forgotten history?

Joshua Oppenheimer: In the United States, yes. To the extent that it was reported at all—it was reported as good news. A victory over communism. It was a pivotal moment for the “domino theory” containment of communism in Southeast Asia.

Morris: Communism had been contained. The dominos have been swept off the map. At least in Indonesia.

Oppenheimer: It’s worth looking at how the story is forgotten and isn’t forgotten in Indonesia itself. How it is remembered and isn’t remembered. In my film, you see the gangsters boasting about it. But in the official history, the story is not spoken about, really. “There were these cruel Communists. They were everywhere, and then we beat them, and then they were gone, and we don’t talk about what happened to them.” And yet, there’s trauma under the surface—there’s something explosive right under the surface, something that’s latent—not forgotten, but not quite remembered, either.

Oppenheimer explained to me that Indonesia had fought a war of independence against the Dutch from 1945 to 1949. Indonesia is “a huge country,” he said, “the size of the United States,” and “the fourth-biggest country in the world by population,” but it was “far poorer at independence than India, for example.” In the 1950s, there was “a struggle for control of the country’s resources, with the Indonesian army on the one side and the workers and the peasants on the other side. They went head to head. And the Indonesian army became very strongly anti-communist with the support of the United States throughout the ’50s.” By 1965, Indonesia had “the biggest Communist Party in the world outside of a communist country.”

Morris: Presumably, the United States saw this as a threat.

Oppenheimer: A huge threat. Vietnam was small and resource-poor compared to Indonesia. The United States was scared of what a communist Indonesia would do, and now they’re doing everything they can with the Indonesian army to stop the Communists. And by 1959, the army had already forced Sukarno to allow no further elections, creating, effectively, a country governed by martial law regime. The purpose of this was, of course, to stop the rise of the Communist Party through the electoral process.

Morris: All leading up to Sept. 30, 1965.

Oppenheimer: Yes, six army generals were killed by a group of junior officers on Sept. 30, 1965. There was supposedly evidence that these generals were involved in a CIA-sponsored coup attempt against Sukarno, who was increasingly dependent on the Communist Party, and was seen as an enemy of the United States—someone who was risking going communist. And it’s highly likely that there was indeed a U.S.-planned coup.

Courtesy of Bernard Safran/TIME; Courtesy of TIME

Morris: To replace Sukarno?

Oppenheimer: To replace Sukarno. Seven generals were targeted. Six ended up getting killed, and their bodies were dumped in a well. Suharto was tipped off. He was told, “This is going to happen.” He certainly didn’t warn the commanders who were above him. He let it happen and then he swiftly moved to crush it and to capture or kill the people involved.

Morris: And the Sept. 30 attempted coup became the pretext for a counter-revolution?

Oppenheimer: Yes, and in fact there is abundant evidence that the Communist Party was not behind the killing of the six generals, but nevertheless the killing of the six generals was used as a pretext to “exterminate the communists.” Since 2000, all these papers have been declassified: letters from the CIA stations in Jakarta and from the embassy to Washington. There was a concern that the army would stop at the officers behind the killing of these generals. “What if they don’t go far enough? This is our opportunity to go against the whole PKI [the Communist Party of Indonesia]. Let’s go against all of them.” You can see that the United States made it very clear that, as a condition for future aid, the Indonesian army must go after the whole Communist Party. And they had guys in the State Department compiling death lists for the army—communist leaders, union leaders, intellectuals who were left-leaning. The signal from the U.S. was clear: “We want these people dead.”

3. The Pale Cast of Thought

Often the study of history is like pulling on a thread: Some detail catches your attention and leads to something else, another detail. A narrative slowly unraveling, slowly revealing something behind it, something hidden or forgotten. Not just the story of a crime, but the story of interconnected crimes.

Is this a story about Indonesia or also a story about us? Oppenheimer had said that the killings were facilitated by the State Department and the CIA. Was this true?

Photo by Abbie Rowe/PhotoQuest/Getty Images

I had picked up Economists with Guns: Authoritarian Development and U.S.-Indonesian Relations, 1960–1968, a book by Bradley Simpson, professor of history at Princeton. I didn’t have to read far: The first pages recapitulate the relevant history leading to the violence. Simpson calls it “an army-led and U.S.-backed campaign of extermination.”

“The annihilation of the largest non-bloc Communist party in the world vividly undermined the rationale for the escalating U.S. war in Vietnam, as former defense secretary Robert McNamara has noted, eliminating at a stroke the chief threat to the Westward orientation of the most strategically and economically important country in Southeast Asia and facilitating its firm reintegration into the regional and world economy after a decade-long pursuit of autonomous development.”

The phrase “undermined the rationale for the escalating U.S. war in Vietnam” caught my attention, as did the reference to McNamara. How was McNamara involved?

I won an Oscar for my film The Fog of War, a profile of McNamara, who was secretary of defense during the Kennedy and Johnson administrations, from Jan. 21, 1961 through Feb. 29, 1968.* The Johnson presidency included the period of the Indonesian killings and the escalation of the Vietnam War. Simpson referred in a footnote to McNamara’s memoir, In Retrospect, a book I thought I knew well. McNamara writes:

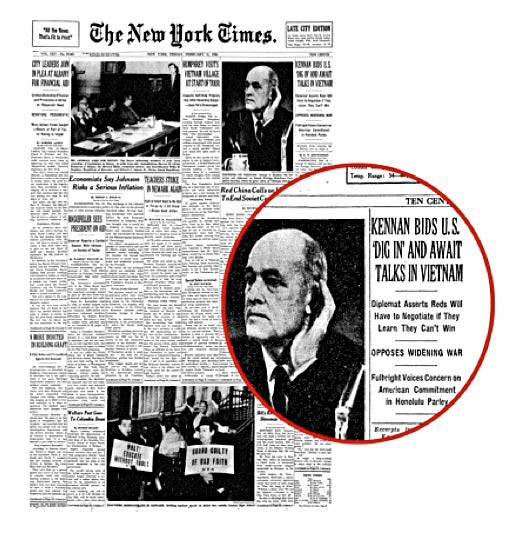

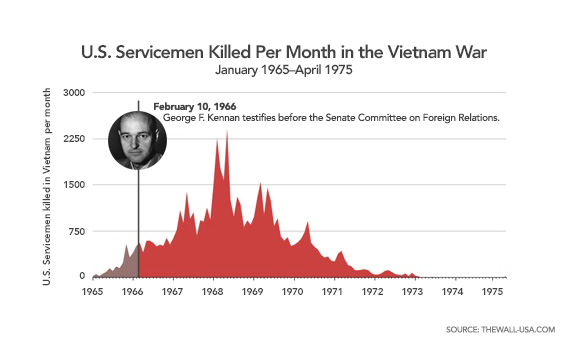

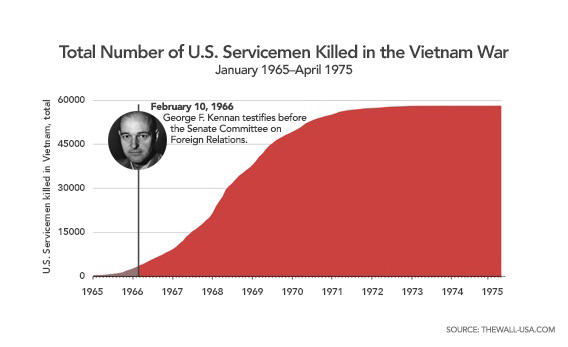

“George F. Kennan, whose containment strategy was a significant factor in our commitment to South Vietnam’s defense, argued at a Senate hearing on February 10, 1966, that the Chinese had ‘suffered an enormous reverse in Indonesia ... one of great significance, and one that does rather confine any realistic hopes they may have for the expansion of their authority.’ This event had greatly reduced America’s stakes in Vietnam. He asserted that fewer dominoes now existed, and they seemed much less likely to fall.”

He concludes, “Kennan’s point failed to catch our attention and thus influence our actions.”

I was shocked. It was a passage that undoubtedly I had read but passed over. But the message was clear. Kennan was saying that the Vietnam War was unnecessary—the invasion of the South and the bombing of the North; the deaths of 58,000 American servicemen and more than 1 million Vietnamese were unnecessary. Not to mention the “collateral damage” to Cambodia and Laos.

Unnecessary.

Had Kennan’s testimony been reported? Yes, on Page 1 of the New York Times, Feb. 11, 1966, top of the fold, right-hand column—the lead story. And although the Times was equivocal, it was clear that Kennan had serious doubts. “Kennan Bid U.S. Dig In.” “Kennan Asserts Reds Will Have to Negotiate if They Learn They Can’t Win.” Followed by “Opposes Widening War.”

And in the Washington Post, a more forthright statement of Kennan’s testimony—a banner across the top of the page, “Kennan Urges U.S. Not to Enlarge War.” Compared with the New York Times, the article was unequivocal.

Kennan, often thought of as the architect of the Cold War, was testifying one year after combat troops landed at Danang in South Vietnam (March 8, 1965) and nine years before the fall of Saigon to the Communists (April 29, 1975). His words are tragic. A Cassandra-like warning that went unheeded. Kennan’s testimony continued,

“There is more respect to be won in the opinion of this world by a resolute and courageous liquidation of unsound positions than by the most stubborn pursuit of extravagant or unpromising objectives … Our country should not be asked, and should not ask of itself, to shoulder the main burden of determining the political realities in any other country, and particularly not in one remote from our shores, from our culture and from the experience of our people. This is not only not our business, but I don’t think we can do it successfully …”

In McNamara’s words, it “failed to catch our attention.” Then. McNamara was re-enacting Kennan’s testimony in his mind—the counterfactual of what might have been but wasn’t. And why it failed to catch his attention. A reminder of Kierkegaard’s famous quotation, “Life can only be understood backward; but it must be lived forward.”

Think of the chronology.

Kennan, in his famous 1947 article “The Sources of Soviet Conduct.” written under the pseudonym “X” for Foreign Affairs, developed the idea of containment of the Soviet Union.

“It is clear that the main element of any United States policy toward the Soviet Union must be that of long-term, patient but firm and vigilant containment of Russian expansive tendencies.”

Kennan later claimed that he had been misunderstood. He claimed that he had come up with a political solution to a political problem, and it had been misinterpreted as a military solution to a military problem. But it became the policy of the Truman administration. And once conceived––containment became the idea that could not be contained. Walter Lippmann, an early critic of containment, called it “a strategic monstrosity” that depended on building “a coalition of disorganized, disunited, feeble and disorderly nations, tribes and factions around the perimeter of the Soviet Union … [which] cannot in fact be made to coalesce … a seething stew of civil strife.” On this count, Lippmann was right. Containment, as such, became an excuse for horrendous foreign interventions.

* * *

McNamara’s quotation from Kennan, Kennan’s testimony, the article on Page 1 of the New York Times, and the coverage in the Post put the story of the Indonesian mass killings into stark relief. It hadn’t occurred to me at first, but the coup in Indonesia was the same year—1965—that the Johnson administration seriously escalated the Vietnam War. Here’s an exchange of telegrams between the U.S State Department and the U.S. Embassy in Jakarta.

“Consulate in Medan, November 16, 1965. Telegram to the Department of State.

Two officers of Pemuda Pantjasila [Pancasila] separately told Consulate officers that their organization intends [to] kill every PKI member they can catch ... He stated Pemuda Pantjasila will not hand over captured PKI to authorities until they are dead or near death …”

The leaders of Pemuda Pantjasila in Medan were Anwar Congo and his friends, the central characters in The Act of Killing.

“Sources indicate that much indiscriminate killing is taking place ...

Attitude Pemuda Pantjasila leaders can only be described as bloodthirsty. While reports of wholesale killings may be greatly exaggerated, number and frequency such reports plus attitude of youth leaders suggests that something like real reign of terror against PKI is taking place.”

Another telegram, coming out of Indonesia and going to the State Department in Washington, D.C., then headed by McGeorge Bundy.

“Ambassador Marshall Green, December 2, 1965. Telegram to the Department of State.

This is to confirm my earlier concurrence that we provide Malik with fifty million rupiahs requested by him for the activities of the KAP-Gestapu movement. [REDACTION]

The KAP-Gestapu activities to date have been important factor in the army’s program, and judging from results, I would say highly successful. This army-inspired but civilian-staffed action group is still carrying burden of current repressive efforts targeted against PKI, particularly in Central Java...

[REDACTION] Our willingness to assist him in this manner will, I think, represent in Malik’s mind our endorsement of his present role in the army’s anti-PKI efforts, and will promote good cooperating relations between him and his army.

The chances of detection or subsequent revelation of our support in this instance are as minimal as any black bag operation can be. [REDACTION]”

Those two telegrams were followed by this one.

“Department of State, December 16, 1965. From William Bundy and Samuel Berger. Telegram to the Embassy in Indonesia.

Appears from here that Indonesian military leaders’ campaign to destroy PKI is moving fairly swiftly and smoothly ...”

* * *

I spoke with Bradley Simpson. I was particularly interested in the McNamara quote from In Retrospect.

Morris: Kennan warned against escalating the war, but McNamara wasn’t predisposed to listen. But what surprised me in your book is not just the idea that the destruction of the PKI eliminated the need for the Vietnam War, but the extent to which the U.S. played a role in all of this.

Bradley Simpson: I went into the project having read all of the literature on the coup attempt, on the Sept. 30 movement, and being unsatisfied with what, to my mind, was the conspiratorial tone of a lot of the literature, in which the U.S. was somehow pulling all these strings and orchestrating events. Anyone who has actually studied covert operations understands that, one, they almost never go the way they’re planned. To the extent that U.S. covert operations have succeeded in overthrowing governments, they almost inevitably succeed in spite of themselves, or they fail a dozen times before they succeed, and then by the skin of a chicken’s teeth.

Morris: But 1965—

Simpson: There is no smoking gun in 1965. There is a lot of smoke but no gun. And I think the best that I could come up with at the time was to demonstrate how, since the late ’50s, U.S. covert operations in Indonesia had been geared toward provoking exactly the kind of clash that took place in late ’65. And that those covert operations accelerated in the summer of 1964 in ways that connect with the expansion of the war in Vietnam. Johnson’s decision to sign off on expanded covert operations in Indonesia takes place right around the time of the Gulf of Tonkin incident. They were looking at all this as a piece.

Morris: But in your book you called it “an army-led and U.S.-backed campaign of extermination.”

Simpson: The CIA was hoping to use black propaganda and some disbursements of money to try and maneuver the Indonesian Communist Party into a position where they would be tempted to do something stupid—given that the U.S. was actually incredibly weak in Indonesia in 1964 and 1965, and had very few cards to play. The paper trail is a lot clearer and the U.S. role is better documented in terms of what the U.S. knew, how much they were encouraging the Indonesian army, and the degree to which they were providing weapons and economic assistance, with the expectation that this assistance was going to be used to exterminate unarmed Communist Party members.

Morris: Can you talk more about the U.S. role in the killings?

Simpson: It was an extraordinarily rapid genocide and the Johnson administration knew about the events as they unfolded, and they made a very deliberate decision to intervene on the side of the génocidaires. The documentary record is clear-cut. And Kai Bird in his biography of the Bundy brothers has McGeorge Bundy saying, basically, “I have a clear conscience. We knew what we were doing. We did what we were doing because we thought it was the right thing to do, and I sleep easy at night knowing that we played the role that we did.”

4. Suit the Action to the Word

I’ll have these players

Play something like the murder of my father

Before mine uncle. I’ll observe his looks,

I’ll tent him to the quick, if a’do blench

I know my course.

—Hamlet, Act 3, Scene 2

Photo courtesy of Criterion Collection/Two Cities Films

The Act of Killing asks the questions—what is history? What is its purpose? Are we simply trying to uncover what really happened in the past? Trying to provide a moral lesson or a cautionary tale for the future? Both? And it tries to address these questions through re-enactments.

The Act of Killing reminds me of the central scene in Hamlet—not the soliloquy, not the testimony of Hamlet’s ghost, not the graveyard scene, but the re-enactment of the murder of Hamlet’s father—the performance of the play, The Murder of Gonzago. Act 3, Scene 2. Or using Hamlet’s more descriptive title, The Mousetrap. The play within the play. The scene where Hamlet attempts “to catch the conscience of the king.”

Hamlet, of course, suspects that his uncle, Claudius, has murdered his father, the king of Denmark, then married his mother, the widow of the murdered king. Hamlet learns from his father’s ghost (or from a ghost that purports to be the ghost of his father), that Claudius really is the killer.

“But know, thou noble youth,

The serpent that did sting thy Father’s life,

Now wears his crown.”

Illustration by Daniel Maclise/Wikimedia Commons

In the play within the play, The Murder of Gonzago, Hamlet asks his actors to “hold a mirror up to nature.” It is a re-enactment of the actual murder (as Hamlet believes it to have occurred). But why did Hamlet stage it? To scrutinize Claudius’ reactions? To provoke him? To serve notice, that he, Hamlet, had solved the crime and knows the identity of the criminal?

Or as Hamlet tells Horatio, is it an attempt to confirm his suspicions that Claudius is the killer?

“There is a play to-night before the king;

One scene of it comes near the circumstance

Which I have told thee of my father's death:

I prithee, when thou seest that act afoot,

Even with the very comment of thy soul

Observe mine uncle: if his occulted guilt

Do not itself unkennel in one speech,

It is a damned ghost that we have seen,

And my imaginations are as foul

As Vulcan’s stithy.”

Re-enactment as a form of historical reckoning. Hamlet asks: Can the play capture the conscience of the king? The Act of Killing asks: Can the play capture the conscience of a nation?

* * *

My discussions with Joshua Oppenheimer turned to the methodology behind his film—the underlying reason for the re-enactments. Oppenheimer’s attempt to answer the question: Who were these men, the killers? Did they see themselves as killers? Of course, there is a difference. In Hamlet’s play within a play actors are re-enacting the murder of his father. Here, the actual perpetrators are re-enacting their crimes. And yet, I was taken by the similarities rather than the differences. The idea that the re-enactment of a crime can tease out hidden thoughts and emotions. Congo asks, “Have I sinned? I did this to so many people, Josh. Is this all coming back to me? I really hope it won’t.”

We discussed my fascination with a scene from Ibsen’s Peer Gynt, the peeling of the onion. The onion represents Peer—his real self. He asks, “Who am I? Who am I, really?” As he peels off each layer, he identifies some aspect of himself. “I’m this ...” And then he peels off another layer. “No, I’m that.” He keeps peeling and peeling, until there’s nothing left. Shards of onion lying at his feet.

That’s the despairing, modernist vision. You get to the bottom of a man, and what is left? A mass of evasion, delusion, confusion—self-deception. And yet, we all believe that there has to be something more—

Photo courtesy of Ernst Emil Aubert/Wikimedia Commons

Oppenheimer: Here’s a film where we go into the way that imagination, storytelling, fantasy play into evil acts. What it means to do something that’s devastating, not just to the people whom you’re hurting and their families, but also to yourself— You have to be acting in a blind spot of self-ignorance in the moment. A kind of blindness. Anwar is talking about the way he used movies not just to get clever methods of killing, but to step out of himself. As he says, coming out of an Elvis movie in a state of trancelike enchantment with the music and the fun of it. All so he could kill happily.

Morris: You use re-enactment in a way that I’ve never really seen before—re-enactment as a way of asking a question about an even deeper mystery, the mystery of who we are, the mystery of what is inside of us—but at the end of the film I actually do not know who this man is.

Oppenheimer: When Anwar’s watching the footage?

We are discussing a scene in The Act of Killing where Anwar Congo is watching the re-enactments of the killings. That is, a scene where he watches himself re-enact the killings. Followed by a scene of Anwar Congo retching on a rooftop.

Morris: Yes. The vomiting—whether the vomiting is one more performance for himself and for us, or if it is the result of something real. Can we ever know?

Oppenheimer: It’s both—in the same sense that an actor can tap into a real emotion through acting or we can make ourselves sad by choosing to remember something and talking about it in a way that makes us sad. It’s definitely both. He’s performing for my camera. He’s certainly aware of the camera and he’s thinking about that. At the same time, he’s performing in such a way that he allows the past to hit him with an unexpected force in that moment.

Morris: I just don’t know.

Oppenheimer: Really.

Morris: Well, you know him and I don’t. All I have to go on is really talking with you and watching the film. But I’m left in the end with a question. I know that there is a past for people, but do they ever deal with it. or do they just try to reinvent it or just make it up out of whole cloth?

Oppenheimer: You’re raising a very, very scary thought. It’s so disturbing in some way that it would’ve been hard for me to maintain my relationship with Anwar, if this were an operating assumption. It could be right. If Anwar doesn’t have a past and also has these at the very most echoes, reverberations or stains from what he’s done that he doesn’t recognize, and if the final moment is maybe yet another moment of performance, if he then disappears into the night and we’re left in this shop of empty handbags, and there’s no connection to the past on that roof, then it’s almost too chilling for me to contemplate what the whole movie is really saying. It’s a disturbing thought.

Real or faux contrition? It goes back once again to Hamlet—now to Act 3, Scene 3. The confession in the chapel. Claudius on his knees. “My offense is rank. It smells to heaven ...” But should Claudius be forgiven while still holding the crown and the queen? “May one be pardon’d and retain the offence?” And his final thought. “My words fly up, my thoughts remain below. Words without thoughts never to heaven go.” Is Claudius saying that his prayers are insincere? That all such prayers are insincere? That mere words can never erase the stain of the terrible crime that he has committed?

* * *

The Suharto regime produced its own film in 1984, called Pengkhianatan G30S/PKI, or Treachery of the September 30th Movement/PKI. It is a government-sponsored false history of what happened in 1965.

The hero of the movie? Suharto himself. When he hears that the Communists have assassinated many of his superiors, he is cautious, deliberate—then finally announces that the army will crush the rebellion and avenge the deaths of the generals. The film ends with his funeral oration at the resting site of the dead generals, pleading with the Indonesian people to carry on.

Pengkhianatan G30S/PKI comes up in The Act of Killing—a few scenes are included. And Adi Zulkadry and Anwar Congo, the two killers at the center of The Act of Killing, are asked about it while getting their makeup done for yet another re-enactment of murder.

Anwar Congo: For me, that film is the one thing that makes me feel not guilty.

Adi Zulkadry: That’s how you feel? Not me. I think it’s a lie. It’s easy to make the Communists look bad after they’re destroyed. Everything is stylized to make them look evil! Communist women dancing naked?

Congo: But we shouldn’t talk about this, Adi. We should talk about our film. We shouldn’t say bad things about the other film to outsiders. What matters is our film.

5. The Conscience of the King

After finding his Senate testimony on Page 1 of the New York Times, I looked through the paper for much of 1966. The troubles in Indonesia were extensively covered. Kennan was not alone in commenting on mass murder in Indonesia. There were articles by Max Frankel, and, in particular, a four-part series that ran from Aug. 22–25, 1966, by Seymour Topping, the chief Southeast Asia correspondent and future managing editor of the New York Times. On Aug. 24, 1966, “Slaughter of Reds Gives Indonesia a Grim Legacy,” the third part, appeared on Page 1.3

I contacted Seymour Topping, now 91 years old. He had recently published a memoir, On the Front Lines of the Cold War. There was a series of chapters on the 1965 coup and the killings that followed. Early in the book, Topping tells a story about his four-part series and the effect it had on LBJ. Johnson didn’t see the Indonesian killings as obviating the need for escalation in Vietnam. Quite the contrary. He saw his aggressive posture on Vietnam as a good thing because it made the killings in Indonesia possible. It was part of the war against Asian communism.

Here’s Topping:

“Transferred from Moscow to Hong Kong as chief Southeast Asia correspondent, I traveled to Indonesia, where I covered the dethroning of Indonesian president Sukarno after the 1965 leftist putsch that brought on the retaliatory purge coup by army generals in which an estimated 750,000 people died. Bill Moyers, press secretary to President Lyndon Johnson, tells of the summer of 1966 when Johnson kept copies of my Indonesia dispatches about the army coup and the genocide that followed ‘in his pocket and on his desk so that he could show them to reporters and visiting firemen.’ Johnson was contending then that his stand in Vietnam had emboldened the Indonesian generals to crush the Communist bid for domination of the archipelago.”

I suppose it’s part of an endless discussion about cause and effect. About history. Did LBJ’s actions in Vietnam embolden the right-wing generals in Indonesia, and as a result help to make the 1965 coup possible? Did the coup obviate the need for the further escalation of the Vietnam War? No more falling dominos, at least in Indonesia. That much was clear to Kennan.

Cullen Murphy, the former editor of the Atlantic and now an editor at Vanity Fair, wrote to me about these issues.

“I was struck by the insidious circularity of the Indonesia/Vietnam dynamic. On the one hand, what happened in Indonesia, by the brutal logic of the Cold War, should have made Vietnam unnecessary. On the other hand, the Vietnam War, by the brutal logic of the Cold War, and as LBJ argued, made what happened in Indonesia possible. Don’t we have to stop thinking this way? But it's the part of the imperial British outlook that was transferred intact into the Washington mindset during the course of World War II––like one of those pathogens carried to a new host by an organ transplant.”

Courtesy of the New York Times

Kennan’s attempt to stop the escalation of the Vietnam War reminds us that if you’re trapped in a narrative, you’re not interested in anything that might contradict that narrative. You’re simply not going to listen. (Doors closed; lights out.) You’re not interested in revisiting the assumptions on which your narrative is based. Kennan wrote about being “enslaved to the dynamics of a single unmanageable situation—to the point where we have lost much of the power of initiative and control over our own policy.”4

Oppenheimer’s The Act of Killing opens with questions about historical amnesia. Is it possible to forget about (or to condone) the deaths of 1 million people? It is much easier for us, probably, to imagine such a thing happening in a developing nation. But what started with a story about Indonesia became for me a story about America. About the deep link between Indonesia, Vietnam, and the United States. And our ability to forget.

Have we erased the memory of what happened? Have we denied our own complicity?

When Kennan testified in February of 1966, the real carnage had not yet begun. Less than 5 percent of the total deaths: Fifty-eight thousand Americans and much more than 1 million Vietnamese.

* * *

On Sept. 26, 2002, 35 years later, Kennan spoke out again. Ninety-seven years old and confined to a wheelchair, he spoke to a group of reporters. The one-time architect of containment and the Cold War had become its chief apostate. It was an admonition and a warning. And a re-enactment of what Keenan knew about war. But this time, his remarks were not extensively reported. They did not appear in the New York Times, let alone on Page 1. Nor did they appear in the Washington Post. I know about them because Mark Danner quoted from them in his 2006 article “Iraq: The War of the Imagination,” in the New York Review of Books. Here is what Kennan said:

“Anyone who has ever studied the history of American diplomacy, especially military diplomacy, knows that you might start a war with certain things on your mind as a purpose of what you are doing, but in the end, you found yourself fighting for entirely different things that you had never thought of before ... In other words, war has a momentum of its own and it carries you away from all thoughtful intentions when you get into it. Today, if we went into Iraq, like the president would like us to do, you know where you begin. You never know where you are going to end.”

The interview took place in the apartment of former Sen. Eugene McCarthy, whose anti-Vietnam War campaign in 1968 was endorsed by Kennan. Kennan was asked to compare Bush and LBJ—Bush’s request to Congress to go to war in Iraq and LBJ’s request to Congress to go to war in Vietnam—the 1964 Gulf of Tonkin Resolution. Kennan was adamant—such resolutions “lead to no good ... You have to look at things all over again, every day, every week, every month, and adjust what you are doing, but do it in the light of the experience of the past ... There is a very, very basic consideration involved here, and that is that whenever you have a possibility of going in two ways, either for peace or for war, for peaceful methods or for military methods, in the present age there is a strong prejudice for the peaceful ones. War seldom ever leads to good results.”

Among other things, Kennan was delivering an argument for the importance of history. “You have to look at things all over again, every day, every week, every month, and adjust what you are doing, but do it in the light of the experience of the past ...” Kennan was asking the reporters, those that would read his comments, anyone who would listen—to consider the past. And yet, the past in 2002 had been all but forgotten.

I returned to Kennan’s remarks as quoted in the New York Times on Feb. 11, 1966, but I wanted to read the entire transcript of what he had said to the Senate Foreign Relations Committee. It’s not online. It can be found in Foreign Relations of the United States. Long, eloquent, and impassioned, Kennan’s testimony concluded with a quote from John Quincy Adams—his July 4, 1821 address to Congress.

“Wherever the standard of freedom and Independence has been or shall be unfurled, there will [America’s] heart, her benedictions and her prayers be. But she goes not abroad, in search of monsters to destroy. She is the well-wisher to the freedom and independence of all …”

I would like to thank my interviewees—Bradley Simpson, Joshua Oppenheimer, and Seymour Topping—and other people who I talked to for this project—Ron Rosenbaum, Michael Witmore, Mark Danner, Tom Luddy, Cullen Murphy, Fredrik Logeval, and John Roosa. There were the people who read the piece and checked the facts—Jessica Melvin, Yvonne Rolzhausen, and George Kalogerakis. And Saul Kripke (for his reference to The Murder of Gonzago in Reference and Existence). I’d like to thank Ann Petrone and Max Larkin for helping research and edit the piece. And of course, my wife, Julia Sheehan.

Correction, July 15, 2013: This essay previously listed the dates for the beginning and end of the Johnson administration where it should have had the dates on which McNamara assumed and then left the office of secretary of defense.