Could Beyoncé Get in Trouble for Stealing Dance Moves?

Plus: Can a town really ban dancing, like in Footloose?

Evidence surfaced on Monday that Beyoncé may have cribbed dance moves from a Belgian choreographer, Anne Teresa de Keersmaeker, for her new music video “Countdown.” Certain scenes in the video do appear almost identical to a 1997 film version of de Keersmaeker’s 1983 work “Rosas danst Rosas,” both in terms of movement and design. Is it really possible to steal a dance?

Yes, but it depends on what you mean by dance. A whole work of set choreography—for example, Balanchine’s Swan Lake—is covered under intellectual copyright law and can certainly be stolen, but only if it meets three legal requirements: First, it must represent “the composition and arrangement of dance movements and patterns usually intended to be accompanied by music”; second, it must be provably original (and not just a performance of someone else’s work); and third, it must exist in a fixed and tangible form. To satisfy this last requirement, dances are usually recorded on film or translated into some form of written notation. If a dance work passes these tests, then its ownership can be claimed by the original choreographer, the company that performed it, the organization that commissioned it, or anyone else who has an appropriate claim given the nature of its creation.

Copyright law does not cover individual dance moves or “phrases,” however. As in music, where single notes or even short sequences of notes cannot be owned (how would anyone make new music otherwise?), individual movements are similarly free from restrictions. A good example of this might be a famous move like the “shimmy.” Though its giggly pattern of gyrations is certainly distinctive, the maneuver is not itself so elaborate as to be considered a “work” and is therefore available to any music-video producer who wishes to deploy it. Ballet elements like the plié or the arabesque fall into the same category.

In Beyoncé’s case, the fact that she copied not only choreography but also closely mimicked scene design and costuming may put her at risk for legal action, since these things taken together are more likely to be viewed by the courts as a version of de Keermaeker’s piece. Even if the pop star is legally excused, she may be deemed a villain by the modern-dance community. This is the second time this year that Beyoncé has been accused of being suspiciously “inspired” by a contemporary artist’s work.

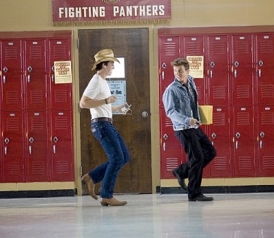

Bonus Explainer: A remake of the 1984 film Footloose opened in theaters on Friday. The original plot followed the struggle of a group of American youth in their quest to subvert and overturn their small town’s religiously motivated ban on dancing. Can a town really do this?

Yes, in a manner of speaking. Municipalities can set zoning regulations and noise ordinances, which delineate those forms of entertainment—such as dancing—that may be enjoyed in public spaces. In many cities, establishments must apply for a separate license, in addition to a liquor or restaurant permit, in order to legally facilitate dancing. Of course, patrons inspired to dance on their own cannot be punished; it’s just advertising, organizing, and general facilitation that are restricted.

The events in Footloose are based on those from the case of Elmore City, Okla., which, until 1980, had a law on the books dating from 1861 that forbade public dancing anywhere within the city limits. Many people held private dances in their own homes—this cannot be regulated—but dancing in public space was off-limits until students fought and won a battle to hold their high-school prom with the wary permission of the school board.

While most cities do not have such draconian regulations, specific instances of dance prudery do arise from time to time. In 1990, for example, a group of high-school students living in the town of Purdy, Mo., brought their challenge to a ban on school dances all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court, only to be denied a hearing. (The judges rendered their decision without comment, leaving in place the lower court’s finding that such policies were in the purview of the school board, regardless of the nature of their motivations.) Similarly, a 2007 case testing a New York City cabaret law dating from the Prohibition era failed to pass muster with the New York State Supreme Court’s Appellate Division; the court noted that dancing is “not a form of expression protected by the federal or state constitutions.” Meanwhile, school boards around the country have often imposed their own bans on specific forms of youthful dancing, especially the grinding or “freak” varieties.

Got a question about today’s news? Ask the Explainer.

Explainer thanks the Dance Heritage Coalition Inc.