Symmetrical Lines and Social Comforts

Samuel Johnson’s simple, restrained poem is everything that death is not.

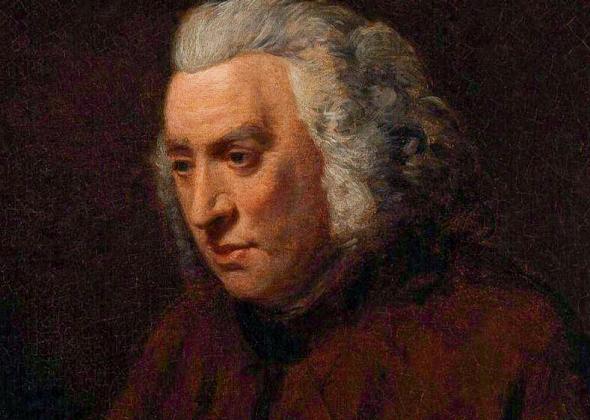

Painting by John Opie/National Portrait Gallery via Wikimedia Commons

Here is a great poem that may mark a significant divide, between readers who treasure Samuel Johnson’s “On the Death of Dr. Robert Levet” and those who don’t much like it.

The theory would be that the poem exemplifies an extreme polarity: pre-modern vs. modern; conventional vs. postmodern; rational vs. irrational; cooked vs. raw; Apollo vs. Dionysus; cool vs. funky. As to technique, metrical vs. free would be the least of it. For some, Johnson’s 36-line poem might resemble one of those quick personality tests that float around the Web.

But those handy pairs of opposites are too neat. They fall short of the poem’s reality, for me—a feeling I’ll try to explain in personal terms.

I was a teenager when I first read the poem in a course, Eighteenth-Century Literature, taught by Paul Fussell. Years later Fussell would write The Great War and Modern Memory, a landmark meditation on war, with World War I as the defining modern example. Indirectly, implicitly, that book is generated by Fussell’s experience as a young infantry officer in World War II. The book is dedicated “To the Memory of Technical Sergeant Edward Keith Hudson, ASN 36548772, Co. F, 410th Infantry, Killed beside me in France, March 15, 1945.” Fussell himself was wounded, with terrible scars on his legs and torso (something he would never allude to; I read about the scars decades later, in an account published by his brother).

When I took his course, the book about war was years ahead in my teacher’s future. The scars were hidden by his expensive-looking suits. To a classroom full of state university boys (Rutgers College was still single-sex), he embodied the period he taught, the Augustan 18th century: superior, witty, rationalistic, urbanely skeptical and precise. He lived in Princeton, but to his credit he told us that there were many more surviving 18th-century structures in New Brunswick than in Princeton, with its fake-historical clapboards and lattices.

We fuzzy-cheeked literary undergraduates were reading, outside any course, the new young writers: Alan Dugan, Allen Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac, Norman Mailer, Flannery O’Connor. Thanks to another course taught by Fussell, I was also devoted to the poetry of Emily Dickinson, Gerard Manley Hopkins, and William Butler Yeats. Ezra Pound’s ABC of Reading had been my textbook.

In other words, I had discovered a lot of ecstatic and tormented verbal music and color. I wasn’t prepared to be thrilled by personified abstractions like the “Affection” and “Arrogance” of Johnson’s poem. Quite the opposite: I had learned from Pound to “go in fear of abstractions” so I might scorn phrases such as “fainting Nature” and “hovering Death” without recognizing the realities they identify precisely. As to idiom and idiom’s relation to form, I had learned to value writing that incorporated the jaggedness of actual, natural speech. Instead of that, Johnson’s elegy for Dr. Levet was based on balanced, symmetrical lines: “By sudden blasts, or slow decline”; “Obscurely wise, and coarsely kind.”

Fussell showed, with a few remarks, how to hear the poem as a masterpiece of emotional truth. He also gave us bits of useful information, explaining that “Dr.” was a kind of polite term, not particularly grand, and that Levet was one of the dependent, more or less indigent people Samuel Johnson gave permanent shelter, in his own house. He explained that officious in Johnson’s time meant something more like dutiful or professional than its negative, modern sense.

I also remember my teacher telling us a truth I recognized even then, without yet experiencing it: that the longer we live, the more death deprives us of “social comforts.” Beyond our possible great losses, which are relatively few, to live is to feel an ever-increasing multitude of smaller but meaningful losses. People die who have been, in Johnson’s quietly perfect phrase, “social comforts”—a lighting bolt of understatement.

Comfort is what the humble, unassuming Levet provided the people to whom he brought a measure of medical care. Caretaking, providing comfort, doing your job: The poem celebrates these attributes, more reliable than the larger but delusive objects of “Hope”—that dark and many-tunneled “mine.” An ambitious, revered literary man, the author of the first English dictionary, Johnson implicitly honors the virtues of Levet as a kind of opposite to his own literary toil, with its high aspirations less reliable than Levet’s “modest wants.” Levet’s virtues, in contrast to Johnson’s own prodigious gifts, “walked their narrow round.” Alluding to the Christian parable of the talents, the poet pays homage to Levet’s management of his ability, never withholding it: “No summons mocked by chill delay / No petty gain disdained by pride.” The poem celebrates virtues that are strikingly different from its own qualites of eloquence, penetration, and scope.

The symmetry, the abstractions, the formal but plain idiom all convey balance and decency before the social realities of death. Equally moving, Johnson also presents some of death’s more urgent, practical realities: pain, dementia. Levet, as though in reward for his modesty and generosity helping other people, himself dies easily, “the nearest way”: “with no throbbing, fiery pain / No cold gradations of decay.” As with the social comforts, time exacts a price. The longer anyone lives, the more serious becomes the possibility of life ending with either pain or diminishment.

Yet the poem is a celebration, more than a lament, far less a complaint. Both Levet’s caregiving and the poet’s mastery of his art exemplify triumphantly the best in people. My teacher, when he was about the age of us college students, had seen a lot of death, in a multiple, violent, and ugly form. He had witnessed and experienced “throbbing fiery pain.” I don’t know how explicitly he thought about that early, crucial wartime experience in relation to “On the Death of Dr. Robert Levet.” It would not be Paul Fussell’s style to deflect attention from Johnson’s poem by raising such a merely personal question. I’m grateful to him for showing me the enduring—and I find, increasing—power in this work of art.

“On the Death of Dr. Robert Levet”

Condemned to Hope’s delusive mine,

As on we toil from day to day,

By sudden blasts, or slow decline,

Our social comforts drop away.

Well tried through many a varying year,

See Levet to the grave descend;

Officious, innocent, sincere,

Of every friendless name the friend.

Yet still he fills Affection’s eye,

Obscurely wise, and coarsely kind;

Nor, lettered Arrogance, deny

Thy praise to merit unrefined.

When fainting Nature called for aid,

And hovering Death prepared the blow,

His vigorous remedy displayed

The power of art without the show.

In Misery’s darkest cavern known,

His useful care was ever nigh,

Where hopeless Anguish poured his groan,

And lonely Want retired to die.

No summons mocked by chill delay,

No petty gain disdained by pride,

The modest wants of every day

The toil of every day supplied.

His virtues walked their narrow round,

Nor made a pause, nor left a void;

And sure the Eternal Master found

The single talent well employed.

The busy day, the peaceful night,

Unfelt, uncounted, glided by;

His frame was firm, his powers were bright,

Though now his eightieth year was nigh.

Then with no throbbing fiery pain,

No cold gradations of decay,

Death broke at once the vital chain,

And freed his soul the nearest way.