American Hero

William Carlos Williams’ poem “Dedication for a Plot of Ground” tells the ordinary and remarkable American immigrant story.

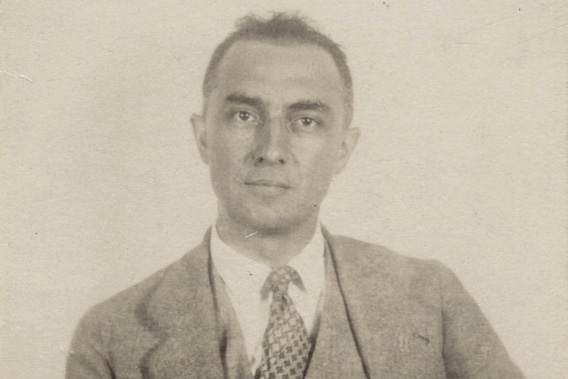

Courtesy of the Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library/Yale University/Wikimedia Commons

What might an American hero-poem be? Longfellow invented literary folk-narratives, Whitman invented himself. Later poets as different as John Ashbery and Elizabeth Bishop have elevated ordinary American language and life by incorporating sly, almost covert allusions and quotations from the historical, European voices of (for example) Andrew Marvell, William Wordsworth, Charles Baudelaire: a way of finding the heroic element in the ways and echoing accents of culture itself.

An early poem by William Carlos Williams gives us a heroic life more familiar and more modern than Longfellow's “Paul Revere” or “Hiawatha,” more pragmatic and driven than Whitman. The story he tells is the ordinary and remarkable American immigrant story.

One thing I like about this poem is the way it is hard to follow. I recognize not only the immigration story, but the confusing, disorderly, partial nature of that story as well. Williams' account of his grandmother's life involves not only the quirks of displacement, but a messy cloud of marriages and separations, custody struggles and dislocations, betrayals and persistence, all compounding one another. That is, this poem's story, and its abrupt, condensed manner of telling the story, resembles most of the American family stories I know, and the way I have heard them. Specifically, personally, the poem reminds me of the difficulty I had, as a child, following the knotted, fragmentary narratives of my grandparents and their parents, siblings, mates, children.

Like most family trees, the one that includes the life of Emily Dickinson Wellcome has more interruptions, twists, and enigmas than clear symmetries. Williams' almost impatient tone, sharp and recklessly quick, is part of his tribute to that woman, the poem's hero. Hers is a story of meaning and intention that persist through the turmoil of her odyssey.

In a nontraditional way, Williams accomplishes some traditional purposes of poetry: to recount a hero's deeds and to celebrate the ancestors. The genealogy is a tangle, far from plain—and the American expression of the poem's final two syllables is, gloriously, as plain as can be.

In another prolonged journey, this is the final installment of Slate's weekly poems, begun with the first issue, in 1996. Seventeen years as poetry editor: a long and pleasurable run. Links to Classic Poem discussions, and eventually some new ones, will appear on my personal website, www.robertpinskypoet.com. And I will be writing for the magazine from time to time. My heartfelt thanks to Slate's founding editor, Michael Kinsley, and his successors—and to the many Slate poetry readers, especially those who have appeared in The Fray and Comments section.

Click the arrow on the audio player to hear Robert Pinsky read “Dedication for a Plot of Ground.” You can also download the recording.

“Dedication for a Plot of Ground”

This plot of ground

facing the waters of this inlet

is dedicated to the living presence of

Emily Dickinson Wellcome

who was born in England; married;

lost her husband and with

her five year old son

sailed for New York in a two-master;

was driven to the Azores;

ran adrift on Fire Island shoal,

met her second husband

in a Brooklyn boarding house,

went with him to Puerto Rico

bore three more children, lost

her second husband, lived hard

for eight years in St. Thomas,

Puerto Rico, San Domingo, followed

the eldest son to New York,

lost her daughter, lost her “baby,”

seized the two boys of

the oldest son by the second marriage

mothered them—they being

motherless— fought for them

against the other grandmother

and the aunts, brought them here

summer after summer, defended

herself here against thieves,

storms, sun, fire,

against flies, against girls

that came smelling about, against

drought, against weeds, storm-tides,

neighbors, weasels that stole her chickens,

against the weakness of her own hands,

against the growing strength of

the boys, against wind, against

the stones, against trespassers,

against rents, against her own mind.

She grubbed this earth with her own hands,

domineered over this grass plot,

blackguarded her oldest son

into buying it, lived here fifteen years,

attained a final loneliness and—

If you can bring nothing to this place

but your carcass, keep out.