Crazy in Love

For Valentine’s Day, a poem Ezra Pound called “the most beautiful sonnet in the language.”

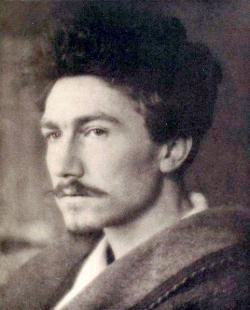

Photograph via Alvin Langdon Coburn/Wikipedia.

As a Classic Poem suitable for Valentine's Day, here is a vivid one about crazy, driven love.

Love and insanity have a long association. Expressions like “crazy about you” suggest both the depth of the link and how automatic or superficial it has become. One thing art does is revitalize such fossilized bits of culture.

And the revitalizing art doesn't need to be new. Mark Alexander Boyd's sonnet was written over 400 years ago, in Scots, but I find emotion and freshness in it every time. It has the sound of conviction. Even in this month of love-rhetoric in the Valentine card, traditional or ironic, Boyd's words, in an essential paradox of art, feel real because of how artfully they are put together. Ultimately, there's no way of saying what makes a poem good in this way: It's a mystery, and largely a mystery of sound, which is to say, beyond a certain point it is beyond analysis.

For me, part of the poem's effect comes from a collision or blending of cultures, a phenomenon of meaning not limited to the modern world. All history is multicultural, I think. The combination of the Scots language and classical mythology is part of the meaning. The effect of Boyd's northern tongue is not merely quaint: Like any idiom it suggests a civilization, and my sense of wonder at the poem is heightened by (for example) the grace and wonder of the Northern word “bairn” applied to a Mediterranean god of love, the Greco-Roman blind infant Eros or Cupid.

Like many other readers, I first encountered this poem in Ezra Pound's ABC of Reading. Still in my teens, I knew so little that I formed two vivid images from Boyd's lines:

Unhappy is the man for evermair

That tills the sand and sawis in the air

I saw the desperate lover as an insane ploughman tilling the beach and also—even more demented by love—as a carpenter pumping his hand saw across thin air; the lover's futile effort to build something out of air with his saw seemed even crazier than his futile effort to make something alive grow out of the sand. In time, the straightforward agricultural definition that “sawis” = “sows” was explained to me, but the ghostly, mistaken image of sawing the air remains in my imagination.

Pound says in his note about the poem “I suppose this is the most beautiful sonnet in the language, at any rate it has one nomination.” That statement's airy, nearly offhand assertiveness is characteristic. Pound as critic is a charming, persuasive bully: a great ear and a defective mind. Does the reckless confidence that makes ABC of Reading so valuable have the same roots as the actual diagnosis of insanity—literally and not as a literary trope for love—that saved Ezra Pound from being executed for treason? His anti-American, anti-Semitic, pro-fascist broadcasts for Mussolini have been much discussed. Possibly, there's not much more to say about them. A good adjective about the matter has been attributed to Czeslaw Milosz: “To be fooled by Stalin—okay. But to be fooled by Mussolini?—unintelligible.”

Unintelligible or repulsive in large ways, Pound did have that gift of the ear. His translations of the 13th-century poet Guido Cavalcanti, for example, are marvels of grace. (The reader has to grant Pound a peculiar, invented archaic English, with not only “thee” and “thou” but words like “gonfalon”: It means a banner or insignia.) The sonnet in which Cavalcanti writes to his friend Dante Alighieri presents an implicit standard for all love poetry. Is the artist really concerned with the one he claims to love, or is the poem just an occasion for showing off?

Click the arrow on the audio player below to hear Robert Pinsky read Guido Cavalcanti's "Sonnet XXIV."You can also download the recording or subscribe to Slate's Poetry Podcast on iTunes.

“Sonnet XXIV”

Dante, I pray thee, if thou Love discover

In any place where Lappo Gianni is,—

If't irk thee not to move thy mind in this,

Write me these answered: “Doth he style him 'Lover'?”

And, “Doth the lady seem as one approving?”;

And, “Makes he show of service with fair skill?”;

For many a time folk made as he is, will

To assume importance, make a show of loving.

Thou know'st that in that court where Love puts on

His royal robes, no vile man can be servant

To any lady who were lost therein;

If servant's suff'ring doth assistance win,

Our style could show unto the least observant,

It beareth mercy for a gonfalon.

Cavalcanti's poem, in English as well as in Italian, brings high standards to courtship, with courtly grace. I love this weird, unmodern translation by a modernist. How can something so good be done by someone so unintelligibly awful? I don't know. But I am glad to know that poem, and even more grateful for this one:

Click the arrow on the audio player below to hear Robert Pinsky read Mark Alexander Boyd's poem.You can also download the recording or subscribe to Slate's Poetry Podcast on iTunes.

Fra bank to bank, fra wood to wood I rin,

Ourhailit with my feeble fantasie;

Like til a leaf that fallis from a tree,

Or til a reed ourblawin with the win.

Twa gods guides me: the ane of tham is blin,

Yea and a bairn brocht up in vanitie;

The next a wife ingenrit of the sea,

And lichter nor a dauphin with her fin.

Unhappy is the man for evermair

That tills the sand and sawis in the air;

But twice unhappier is he, I lairn,

That feidis in his hairt a mad desire,

And follows on a woman throw the fire,

Led by a blind and teachit by a bairn.

Slate Poetry Editor Robert Pinsky will be joining in discussion of the poems this week. Post your questions and comments on the work, and he'll respond and participate. For Slate's poetry submission guidelines, click here. Click here to visit Robert Pinsky's Favorite Poem Project site. Click here for an archive of discussions about poems with Robert Pinsky in "the Fray," Slate's reader forum.