Don't Look for Smiles

-

Tina Barney, CREDIT: Marina's Room, 1987. "Ektacolor Plus" color print on paper sheet, 48 x 60 inches. Courtesy Smithsonian American Art Museum, museum purchase.

Tina Barney, CREDIT: Marina's Room, 1987. "Ektacolor Plus" color print on paper sheet, 48 x 60 inches. Courtesy Smithsonian American Art Museum, museum purchase.Before laying eyes on "Close to Home: Photographers and Their Families," a modest show drawn from the permanent collection of the Smithsonian American Art Museum, I made a bet: There would be no smiles. It was a good bet, I figured, for what else can distinguish serious artists who photograph their own families from average Joes snapping shots for the family album? Think of Sally Mann's topless, defiant children posing for the camera. Or think of Annie Leibovitz's pictures of her dying father, Sam, and her dead companion, Susan Sontag, laid out. No smiles, naturally.

But if Mann and Leibovitz are your mental images of how professional photographers choose to expose their private lives, you really need to take a look at this show. It is so far from evoking the voyeuristic thrill and horror of Mann and Leibovitz that it isn't even funny. What has taken voyeurism's place? The thrill and horror of seeing photographers and their families fighting over their representation.

-

Larry Sultan, CREDIT: Mom in the Garage, 1988, printed 2000. Chromogenic development print, 29 7/8 x 35 5/8 inches. Courtesy Smithsonian American Art Museum, museum purchase through the Luisita L. and Franz H. Denghausen Endowment.

Larry Sultan, CREDIT: Mom in the Garage, 1988, printed 2000. Chromogenic development print, 29 7/8 x 35 5/8 inches. Courtesy Smithsonian American Art Museum, museum purchase through the Luisita L. and Franz H. Denghausen Endowment.The best-known figures of this strange subgenre of family portrait photography are Larry Sultan (1946-2009), who made a book of photographs of his parents in their suburban home (Pictures From Home) in the 1980s, and Tina Barney (1945-), known for her large-scale Ralph Lauren-esque family pictures. It just goes to show what happens when your subjects aren't small children or dying people. Yes, apparently these models have rights, and they're doing their damnedest to ruin the art.

Almost all of the photos in "Close to Home" are color pictures of well-dressed families in nice clean real estate doing almost lifelike things. They feel far closer to Jeff Wall's slyly constructed dramas—think of his large-scale scene of a man using one hand to hold onto his girlfriend and the other to flip the bird at a fellow pedestrian—than to the confessional portraits that Nan Goldin took of her familylike friends having sex in The Ballad of Sexual Dependency. These families have dressed up. They've cleaned out the garage. They know the cameras are coming. And they are ready.

-

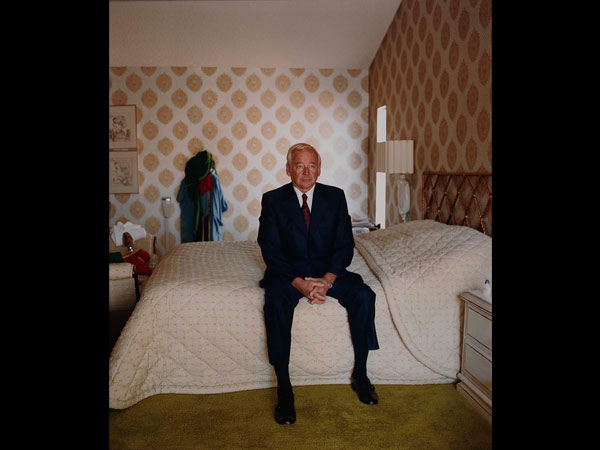

Larry Sultan, CREDIT: Dad on the Bed, 1984. Chromogenic development print 36 x 30 inches. Courtesy Smithsonian American Art Museum, purchase through the Luisita L. and Franz H. Denghausen Endowment.

Larry Sultan, CREDIT: Dad on the Bed, 1984. Chromogenic development print 36 x 30 inches. Courtesy Smithsonian American Art Museum, purchase through the Luisita L. and Franz H. Denghausen Endowment.It turns out that this kind of artistic but consensual family photograph has its own fascination. Here the interest isn't so much in looking at truly private moments but rather in seeing what kind of bargain has been struck between a photographer trying to expose a family secret and a subject resisting.

Consider Larry Sultan's Dad on the Bed. The wall text tells us that Sultan's dad, Irving, had to retire early from his job as a corporate executive with Schick and was "frustrated." But, in fact, Irving said his son had instructed him not to smile. Perhaps he gave him other irritating instructions, too, for the father issued a brilliant little manifesto afterward: "Any time you show that picture," Larry recalls him saying, "tell people that that's not me sitting on the bed looking all dressed up and nowhere to go, depressed. That's you sitting on the bed, and I am happy to help you with the project, but let's get things straight here.'"

-

Carrie Will, CREDIT: Rikki and Carrie, Dining Room, 2007. Chromogenic development print. 19 3/4 x 23 3/4 inches. Smithsonian American Art Museum, museum purchase made possible by David S. Purvis.

Carrie Will, CREDIT: Rikki and Carrie, Dining Room, 2007. Chromogenic development print. 19 3/4 x 23 3/4 inches. Smithsonian American Art Museum, museum purchase made possible by David S. Purvis.OK. Let's get things straight here. These family photos (unlike Sally Mann's or Annie Leibovitz's) are basically self-portraits, whether or not they include the photographer. They tell us about the photographer and what his or her family was willing to put up with. And in some cases the photographers are perfectly aware of—and intent on displaying—just this power struggle. A perfect example is this double portrait of the photographer and her twin.

The drama here lies in figuring out which twin is which, who is predator and who is prey. (And I won't tell you.) They are far from identical. One is watchful. The other seems slightly depressed. One boldly waits for the shutter; the other looks away. This is a picture of the relationship that the twins were having during the shoot and because of the shoot, a picture of a bargain temporarily struck. It's a great photograph of its own occasion.

-

Virginia Beahan, CREDIT: First Day of Spring, New Hampshire, 2005. Chromogenic development print. 18 1/2 x 23 3/8 inches. Smithsonian American Art Museum, gift of Haluk and Elisa Soykan.

Virginia Beahan, CREDIT: First Day of Spring, New Hampshire, 2005. Chromogenic development print. 18 1/2 x 23 3/8 inches. Smithsonian American Art Museum, gift of Haluk and Elisa Soykan.Although this photograph is ostensibly a portrait of Virginia Beahan's 89-year-old mother, who was then suffering from dementia, it is also a portrait of her fine daughter. The mother is wrapped in a blanket enjoying the first rays of spring on acres of New Hampshire land. She is well-cared-for and has her dignity. If she were wasting away in a nursing home, would her daughter, a landscape photographer, have exposed her to our view? Not likely, for that would have been, in effect, a portrait of a derelict and exploitative daughter.

-

Margaret Strickland, CREDIT: Easter Dress. Inkjet print, 17 x 21 inches. Smithsonian American Art Museum, museum purchase made possible by David S. Purvis.

Margaret Strickland, CREDIT: Easter Dress. Inkjet print, 17 x 21 inches. Smithsonian American Art Museum, museum purchase made possible by David S. Purvis.In consensual family photography (which, by the way, seems to be practiced mostly by women), the intentions of the artist don't always come through. Here, the wall text suggests that the photographer, Margaret Strickland, set out to capture her younger sister navigating the social pressures of adolescence in Georgia. But the most memorable thing about this picture is the looming portico. How awkward is that?

This brings up another constant in these consensual family portraits. Scroll back and you will notice that almost all of the photos in this show include not only a portrait but a nice piece of land or house. Is this the legacy of Tina Barney, whose subject was her own privileged circumstances? Or does it mean that all photographers come from rich families? Not at all. Once again, it's a peculiar artifact of this bizarre subgenre. What photographer's family would consent to showing off their own squalor? And what kind of photographer would demand it?

-

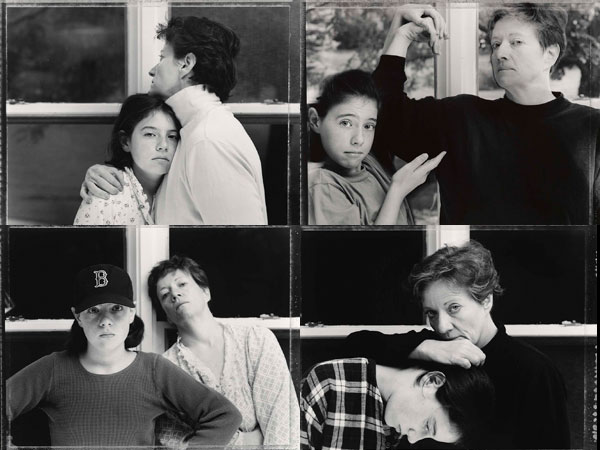

Elaine O'Neil, CREDIT: September 22, 1993, October 7, 1994, April 13, 1995, and April 13, 1996, printed 2005. Gelatin silver prints on paper image: 15 1/4 x 18 1/2 inches. Sheets: 15 7/8 x 19 3/4 inches. Smithsonian American Art Museum, purchase through the Luisita L. and Franz H. Denghausen Endowment.

Elaine O'Neil, CREDIT: September 22, 1993, October 7, 1994, April 13, 1995, and April 13, 1996, printed 2005. Gelatin silver prints on paper image: 15 1/4 x 18 1/2 inches. Sheets: 15 7/8 x 19 3/4 inches. Smithsonian American Art Museum, purchase through the Luisita L. and Franz H. Denghausen Endowment.By the way, I lost my smiles bet. The reason was Elaine O'Neil's great series of tightly cropped, black-and-white photographs taken every day over a five-year period in front of the grid of a window frame, "Mother and Daughter: Posing as Ourselves." In the 10 pictures from this series included in the exhibition, the mother/photographer never smiles, but the daughter does, and sometimes she even mugs for the camera, pointing to her mother in a mocking way.

Despite the fact that the slice-of-life effect is broken by the funny gestures and smiles, these pictures look the most like life. Though mother and daughter are clearly conscious of being photographed, they are the least self-conscious people in the show. They acknowledge the reality that is theirs for that instant, the reality that they are sitting before a camera, posing. Life, they say, is a photo booth, so let's get on with it.