The Dark Art of Cut and Paste

-

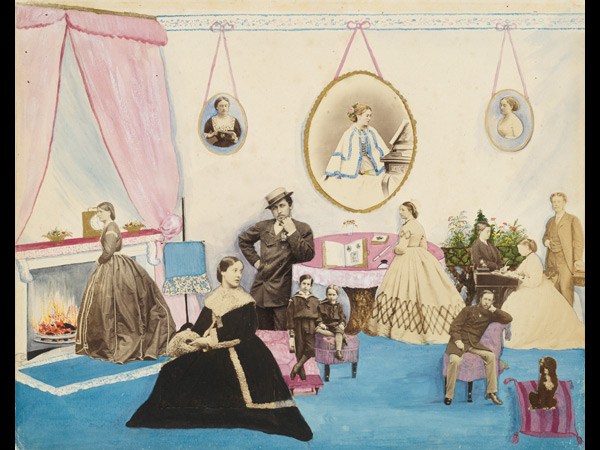

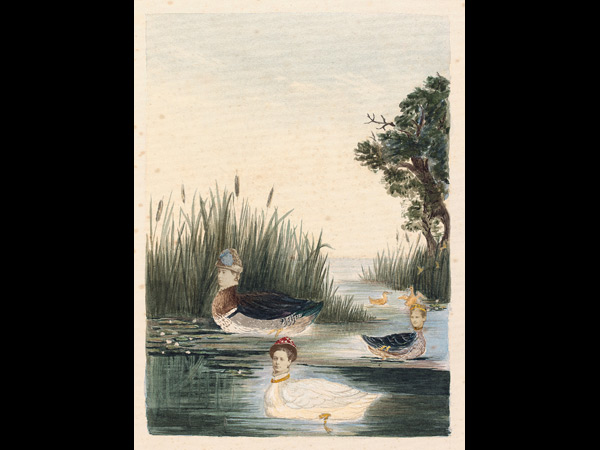

Georgina Berkeley, CREDIT: Untitled Page From the Berkeley Album, 1867-71. Collage of watercolor and albumen silver prints. Musée d'Orsay, Paris. Photo courtesy of Réunion des Musées Nationaux/Art Resource, New York.

Georgina Berkeley, CREDIT: Untitled Page From the Berkeley Album, 1867-71. Collage of watercolor and albumen silver prints. Musée d'Orsay, Paris. Photo courtesy of Réunion des Musées Nationaux/Art Resource, New York.A year or so after Charles Darwin published On the Origin of Species (1859), English ladies started cutting up photos of their friends and relations and pasting bits and pieces of them (particularly their heads) into alien landscapes and onto foreign bodies. Was it just a new pastime, like staging parties or playing the piano–yet another way for Victorian women to show off their class and their wits? Or was it more?

To judge from an exhibition called "Playing With Pictures: The Art of Victorian Photocollage," organized by Elizabeth Siegel for the Art Institute of Chicago and now on view at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the answer is: It was more.

-

Frances Elizabeth, Viscountess Jocelyn, CREDIT: Diamond Shape With Nine Studio Portraits of the Palmerston Family and a Painted Cherry Blossom Surround, From the Jocelyn Album, 1860s. Collage of watercolor and albumen silver prints. National Gallery of Australia, Canberra.

Frances Elizabeth, Viscountess Jocelyn, CREDIT: Diamond Shape With Nine Studio Portraits of the Palmerston Family and a Painted Cherry Blossom Surround, From the Jocelyn Album, 1860s. Collage of watercolor and albumen silver prints. National Gallery of Australia, Canberra.As Patrizia di Bello points out in the catalog, Playing With Pictures, powerful social determinants drove this new art. By the 1860s, cartes de visite—those 2.5-by-4-inch cardboard calling cards with photos on them (the Facebook photos of the day)—were becoming cheap enough for even working-class people to buy, exchange, and collect. So aristocratic women upped the ante by adding artistic touches to the albums in which they kept and showed off their cartes de visite.

Looking through the albums in the exhibition (and the Met has computers that allow this), you'll see many pages of undoctored cartes de visite and then, intermittently, something more interesting. The album-maker arranges her cards into geometric patterns. She adds watercolor garlands around their edges. She lets a dress in a photo rest lightly on some watercolor foliage. Emboldened, she cuts the photos from the cards and pastes heads or bodies onto fanciful backgrounds—a lake, porch, or drawing room—to make groups, scenes, entire narratives.

-

Mary Georgiana Caroline, Lady Filmer, CREDIT: Untitled Loose Page From the Filmer Album, mid-1860s. Collage of watercolor and albumen silver prints. Courtesy of Paul F. Walter.

Mary Georgiana Caroline, Lady Filmer, CREDIT: Untitled Loose Page From the Filmer Album, mid-1860s. Collage of watercolor and albumen silver prints. Courtesy of Paul F. Walter.For this collage, Lady Filmer placed her own portrait (she's the one near the table, posing with her albums) so she could gaze at the Prince of Wales (the guy in the boater leaning on the mantelpiece). Meanwhile, she shoved her tiny husband into a chair in the righthand corner of the scene, near the dog. Like a girl playing with a dollhouse, she set up a new social order, one that displayed both her clout (she's friendly, even flirtatious, with a prince!) and her artfulness (she stands near her pot of glue and paper knife).

-

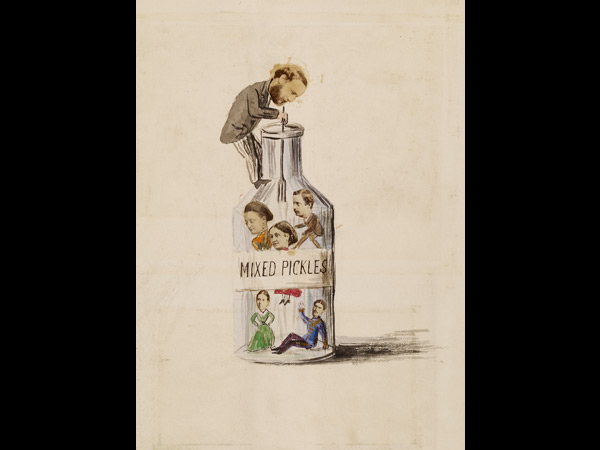

Victoria Alexandrina Anderson-Pelham, Countess of Yarborough, and Eva Macdonald, CREDIT: Mixed Pickles (Detail), From the Westmorland Album, 1864-70. Collage of watercolor and albumen silver prints. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles.

Victoria Alexandrina Anderson-Pelham, Countess of Yarborough, and Eva Macdonald, CREDIT: Mixed Pickles (Detail), From the Westmorland Album, 1864-70. Collage of watercolor and albumen silver prints. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles.But can class rivalry and social aspiration alone explain the bizarre situations in which these Victorian heads sometimes appear? Of course social life is full of slights and barbs, but some of the scenes go beyond that, both in cruelty and invention. This painful-looking scenario titled Mixed Pickles, made by Eva Macdonald and Victoria Alexandrina Anderson-Pelham, countess of Yarborough, shows a man climbing up the side of a glass bottle and poking a fork inside to try to stab one of the pickles, which are, in fact, the photographic heads of people attached to tiny watercolor bodies floating in invisible brine. To be picked out for social or romantic attention, the artists suggest, is not always an unmitigated joy; perhaps sometimes it is better to sink than swim.

-

Maria Harriet Elizabeth Cator, CREDIT: Untitled Page From the Cator Album, late 1860s-'70s. Collage of watercolor and albumen silver prints. Courtesy of Hans P. Kraus Jr., New York.

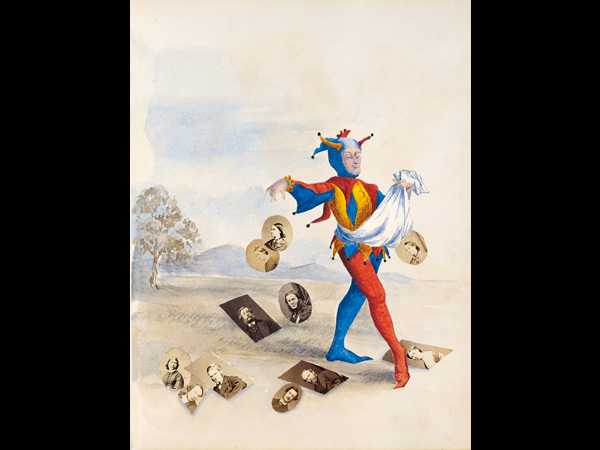

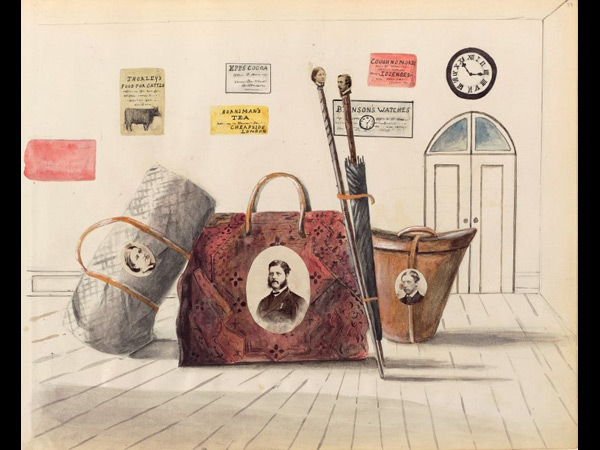

Maria Harriet Elizabeth Cator, CREDIT: Untitled Page From the Cator Album, late 1860s-'70s. Collage of watercolor and albumen silver prints. Courtesy of Hans P. Kraus Jr., New York.Once photos were unmoored from their original surroundings, it appears, something deeper and darker was set loose. You could turn your best friend into an acrobat, strip him down to his skivvies, and have him leap through a hoop of fire. You could transform a neighbor into a bubble, a duck, or the handle of an umbrella. You could splay the bodies of loved ones onto fans, or get them stuck in webs, or turn their heads into seeds and sheets of paper scattered carelessly by a clown.

-

Marie-Blanche-Hennelle Fournier, CREDIT: Untitled Page From the Madame B Album, 1870s. Collage of watercolor, ink, and albumen silver prints. The Art Institute of Chicago, Mary and Leigh Block Endowment.

Marie-Blanche-Hennelle Fournier, CREDIT: Untitled Page From the Madame B Album, 1870s. Collage of watercolor, ink, and albumen silver prints. The Art Institute of Chicago, Mary and Leigh Block Endowment.Here, in a page from the Madame B album, human faces, peering out, become the eyes of a butterfly's wing. It's an eye for an eye. The collagists loved living puns, strange substitutions, scale anomalies, and, at least occasionally, the attendant sadism.

-

Georgina Berkeley, CREDIT: Untitled Page From the Berkeley Album, 1866–71. Collage of watercolor, ink, pencil, and albumen silver prints. Musée d'Orsay, Paris.

Georgina Berkeley, CREDIT: Untitled Page From the Berkeley Album, 1866–71. Collage of watercolor, ink, pencil, and albumen silver prints. Musée d'Orsay, Paris.This is Saul Steinberg's world a century before his time. It is Surrealism 70 years avant la lettre. It is photomontage 60 years before the Dadaists did it in Berlin. It is collage 50 years before the Cubists "invented" it in France. The only artist who seems to anticipate these surreal-looking Victorian collages is J.J. Grandville, the 19th-century French satirical illustrator who drew animals and insects doing distinctively human things.

-

Elizabeth Pleydell-Bouverie and Jane Pleydell-Bouverie or Ellen Pleydell-Bouverie and Janet Pleydell-Bouverie, CREDIT: Untitled Page From the Bouverie Album, 1872-77. Collage of watercolor and albumen silver prints. Courtesy of George Eastman House, International Museum of Photography and Film, Rochester, N.Y.

Elizabeth Pleydell-Bouverie and Jane Pleydell-Bouverie or Ellen Pleydell-Bouverie and Janet Pleydell-Bouverie, CREDIT: Untitled Page From the Bouverie Album, 1872-77. Collage of watercolor and albumen silver prints. Courtesy of George Eastman House, International Museum of Photography and Film, Rochester, N.Y.Why this precocious dip into collage, with its disturbing mix of media, so long before its allotted time in art history? Well, a cluster of big ideas floating around in Victorian England might have had something to do with it—ideas about substitution, transformation, mutation, and the very processes by which one thing can become something else. There are two obvious sources for these ideas, one fictional, one scientific. The fictional one is Lewis Carroll's Alice in Wonderland (1865). The factual one is Charles Darwin's On the Origin of Species (1859).

As the curator of this exhibition notes, Carroll's Alice was a source to be reckoned with and even to be pillaged for its imagery: "[B]y 1870 some twenty thousand copies had been printed, and by 1884 over one hundred thousand were in circulation." Readers loved the "puns and wordplay, misunderstandings, references to dreams, and bizarre transformations." They loved the illustrations, too. One family, the Pleydell-Bouveries, actually traced John Tenniel's drawings and then put photos of children they knew in Alice's place (an amusing twist, in retrospect, since Carroll himself based Alice on a real girl, Alice Liddell, whom he often photographed).

-

Georgina Berkeley, CREDIT: Untitled Page From the Berkeley Album, 1867-71. Collage of watercolor and albumen silver prints. Musée d'Orsay, Paris. Photo courtesy of Réunion des Musées Nationaux/Art Resource, NY.

Georgina Berkeley, CREDIT: Untitled Page From the Berkeley Album, 1867-71. Collage of watercolor and albumen silver prints. Musée d'Orsay, Paris. Photo courtesy of Réunion des Musées Nationaux/Art Resource, NY.The photocollagists, it seems, were especially taken with Carroll's great conceit of playing cards coming to life. They used their paper knives, glue, and watercolors to replace the kings, queens, and jacks in a deck with the heads of aristocrats they knew, giving their friends a nice social bump. And it's not hard to imagine, as Siegel notes, that the scene in which the Queen of Hearts shouts for random beheadings—"Off with his head!" "Off with her head!"—struck a chord. The collagists were, after all, deep into their own beheading ceremonies.

-

Kate Edith Gough, CREDIT: Untitled Page From the Gough Album, late 1870s. Collage of watercolor and albumen silver prints. V&A Images/Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Kate Edith Gough, CREDIT: Untitled Page From the Gough Album, late 1870s. Collage of watercolor and albumen silver prints. V&A Images/Victoria and Albert Museum, London.Irresistible as Alice was, On the Origin of Species may have been the stronger conceptual inspiration. A decade after it was published, Siegel writes, there were 16 different English-language editions. Every educated English reader would have known about Darwin and would have seen his ideas lampooned in "caricatures, songs, and satires in the popular press," including John Tenniel's comical drawings of half-human, half-animal figures. So, when the collagists cut out human heads and put them on animal bodies, they were not just tinkering with the social order, but also grappling with the mind-boggling idea that what is human now was not always so. Who knows? Maybe they were even mischievously suggesting a parallel between the two.

Unlike the many cartoonists who dealt with Darwin by simply plopping his head on a monkey body, the Victorian collagists appear to be trying out Darwin's ideas for size, and in rather personal and subversive ways. In one collage, Kate Gough placed a dozen photos of her family on monkey bodies and set them in a tree. And in this collage of human-headed ducks, she seems to suggest that, yes, stuffy aristocrats can trace their evolutionary roots to preening pond life. She makes her point well. Once you lay eyes on those serene ladies paddling around, breasts swelling with pride, you can really see where they got their splendid bearing.