Ready, Aim—Dream!

-

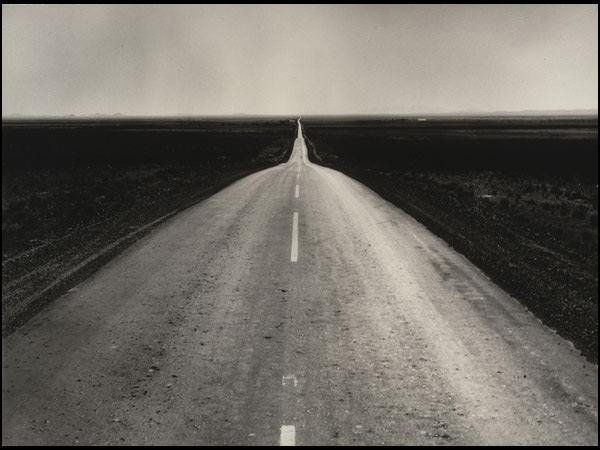

Shut your eyes and picture the great American West. What do you see? The boggling maze of the Grand Canyon, the sun streaming down on Yosemite, the pueblos at Canyon de Chelly, a moonrise over a sleeping New Mexican town, the mitten rock at Monument Valley, the sad profile of an Indian chief, a migrant mother with a worried face, a tornado in Kansas, a geyser in Wyoming, a gusher in Texas, a Marlboro Man on the range, Marilyn Monroe as a misfit, an open road, an endless sky, a surreal suburb, an empty parking lot?

You may be the victim of a great Western fantasy. Whatever image you chose, you can blame photography, which has done more than anything to construct our vision of the West, whether it's cowboys and Indians or parking lots and strip malls. If you have any doubt about this, check out "Into the Sunset: Photography's Image of the American West," an exhibition at MoMA.

As the show's curator, Eva Respini, notes in her catalog essay, photography and the West "came of age together" in the 1840s, and they grew up together. But did they lose their clear-eyed innocence together, too, and if so, when?

-

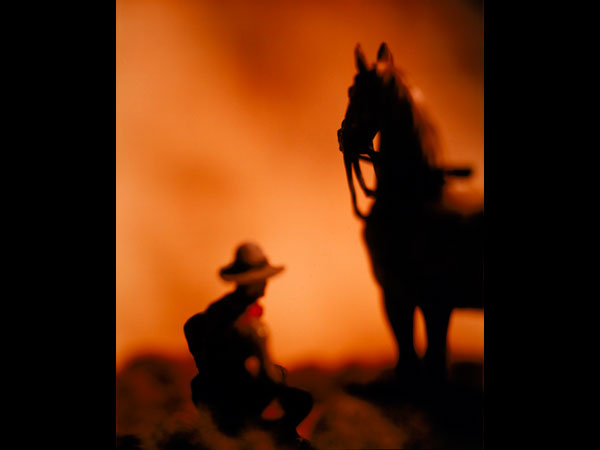

CREDIT: David Levinthal, Untitled, from the series "The Wild West," 1989. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. The Fellows of Photography Fund and Horace W. Goldsmith Fund through Robert B. Menschel © 2009 David Levinthal.

CREDIT: David Levinthal, Untitled, from the series "The Wild West," 1989. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. The Fellows of Photography Fund and Horace W. Goldsmith Fund through Robert B. Menschel © 2009 David Levinthal.The unofficial mascot of the exhibition is the Marlboro Man. There's an evocation of him by David Levinthal, who is known for creating picturesque scenarios with toys. And the opening shot of the show—right at the entrance to greet you—is Untitled (Cowboy), a Richard Prince photo from 2003 that was stolen, adapted, or made—depending on what you think of this artist—from a Marlboro ad. Although the photo looks authentic, it is, at every level, inauthentic. (We were, ironically, unable to get permission to reproduce it here.) Prince didn't really take the picture of the cowboy himself. And even the original photographer wasn't catching a real moment in a cowboy's life; he was just shooting an ad.

Since this "cowboy" is the centerpiece of the show, and since there's nothing true about him, he raises some big questions: Just how wide is the ambit of the Western fantasy? Does the fantasy West created by photography extend all the way back to the 1840s, when photographers first shot the West? Or did it dawn gradually?

Although the exhibition does not really answer these questions or even ask them explicitly, it does include a number of photographs that seem to date from before the end of innocence. So, maybe we can even find the precise moment when innocence and reality were lost—the primal scene.

-

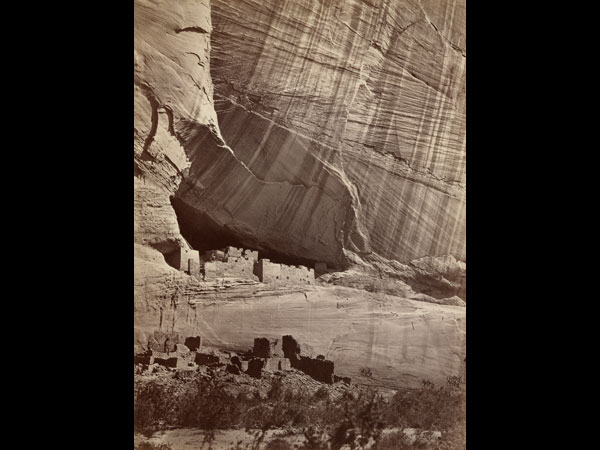

Timothy O'Sullivan, CREDIT: Ancient Ruins in the Canyon de Chelle, 1873. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Ansel Adams in memory of Albert M. Bender.

Timothy O'Sullivan, CREDIT: Ancient Ruins in the Canyon de Chelle, 1873. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Ansel Adams in memory of Albert M. Bender.I'm pretty sure that Timothy O'Sullivan's picture of Canyon de Chelly (1873) is true West. Pure as the driven snow. OK, maybe he worked hard to get that gorgeous striation on the rock wall. Maybe he did wait for the sun to cast the strongest possible shadows. And maybe his use of the vertical landscape format, known primarily from East Asian landscapes, did make the canyon walls look even higher than they are. (The vertical format is one of the best tricks of Western landscape photography. William Henry Jackson and Alvin Langdon Coburn used it, too.) But, hey, O'Sullivan didn't set up the whole canyon. He didn't build those houses in the cliffs. He's not making it all up.

-

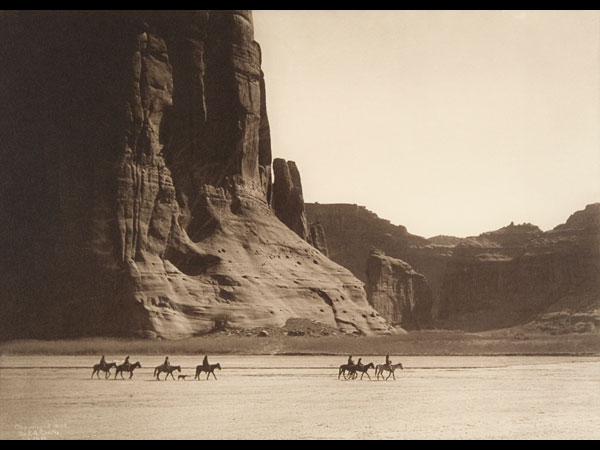

Edward Sheriff Curtis, CREDIT: Cañon de Chelly, 1904. Amon Carter Museum, Fort Worth, Texas.

Edward Sheriff Curtis, CREDIT: Cañon de Chelly, 1904. Amon Carter Museum, Fort Worth, Texas.What about Edward Sheriff Curtis' 1904 photograph of the very same canyon? The curator of the exhibition suggests that this shot is suspect, because here the photographer seized on an opportunity "for the picturesque." The "small Navajo figures cross the barren land on horseback, as at the beginning or the end of a mythic tale." Personally, I see no problem. It's not as if Curtis imported these figures to the canyon. Not everything picturesque is a lie.

-

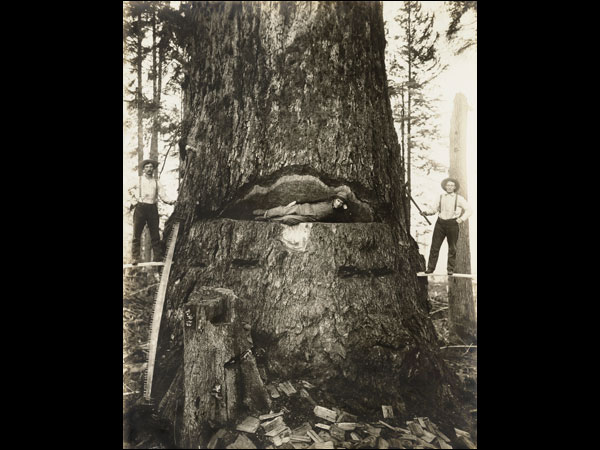

Darius Kinsey, CREDIT: Felling a Fir Tree, 51 Feet in Circumference, 1906. Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Darius Kinsey, CREDIT: Felling a Fir Tree, 51 Feet in Circumference, 1906. Museum of Modern Art, New York.Still, the truth is, once you allow figures into a landscape, it's hard to lock all narrative out. As Arthur Miller said on the set of the movie The Misfits in the Nevada desert: "The people were so little and the landscape was so enormous." It's hard not to see a story there.

Consider Darius Kinsey's 1906 photograph Felling a Fir Tree, 51 Feet in Circumference. Here Kinsey shows part of a large tree, mortally wounded and flanked by small men with axes and saws. In the mouth of the tree's fatal crack lies a man, alive, relaxed, almost smiling. He is a picture of true machismo, casual and radiant in the face of death. Kinsey, who was clearly aiming for a David and Goliath tale, must have set up the shot: "You, there, you crawl into that crack, and I'll pay you a buck!" Still, the man in the maw really must have been brave enough to lie there. So I'd say this is not so much a pure fantasy as a tale of true grit.

-

Timothy O'Sullivan, CREDIT: Savage Mine, Curtis Shaft, Virginia City, Nevada, 1868. Amon Carter Museum, Fort Worth, Texas.

Timothy O'Sullivan, CREDIT: Savage Mine, Curtis Shaft, Virginia City, Nevada, 1868. Amon Carter Museum, Fort Worth, Texas.True grit may be the longest-running Western myth of them all, and it extends to Indians, cowboys, loggers, miners, homesteaders, and migrant farmers. But it certainly didn't start out as a myth. As early as 1855, there are group portraits of rugged homesteaders out on the range with blurry children at their feet. In 1868, Timothy O'Sullivan's Savage Mine, Curtis Shaft, Virginia City, Nevada shows grim miners, all unsmiling, standing with coffinlike carts, ready to descend. No romance there. (Well, the glowing light and the triptych could hint at something religious.) At the turn of the century, Adam Clark Vroman photographed a group of Indians in ordinary dress, looking chilled in front of some cliffs. No artifice there. At some point, each one of these rugged realities did become a fantasy of ruggedness, but just how and when is not clear.

-

Gertrude Käsebier, CREDIT: American Indian Portrait, circa 1899. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Mina Turner.

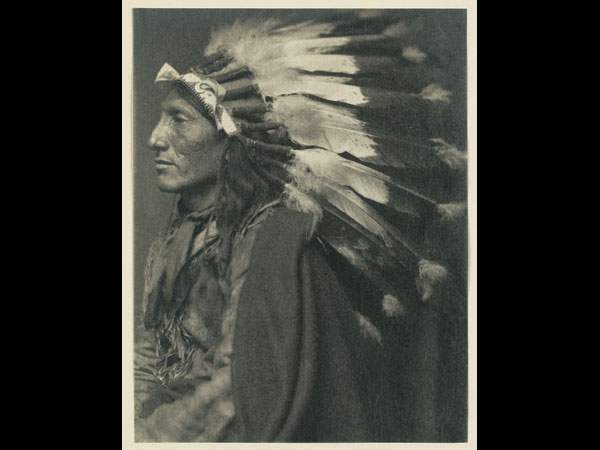

Gertrude Käsebier, CREDIT: American Indian Portrait, circa 1899. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Mina Turner.The blame for the myth of the noble Indian, at one with the land, has often been laid at the feet of Edward Sheriff Curtis, official chronicler of Indian life. Near the end of the 19th century, when it was clear that the Indians were fast disappearing from the American West, a number of photographers, including John K. Hillers, Gertrude Käsebier, and Edward Curtis, started photographing them. The most ambitious project, funded by J. Pierpont Morgan, was carried out by Curtis, who made not only thousands of photographs but also audio recordings.

Maybe it was Curtis' impulse to capture things as they once were (rather than things as he found them) that led him down the path to myth. Curtis apparently staged some of his shots, "sometimes asking his subjects to change into traditional dress and retouching his negatives to erase traces of the modern world," Respini notes. And, she adds, Gertrude Käsebier was similarly guilty: Her photograph of Whirling Horse, taken in profile to show off his headdress, "is an artistic representation rather than an insightful psychological portrait … a romantic cliché." Actually, the thing that stands out most in this portrait by Käsebier, I think, is his bad complexion.

-

Dorothea Lange, CREDIT: Migrant Mother, Nipomo, Calif., 1936. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Purchase.

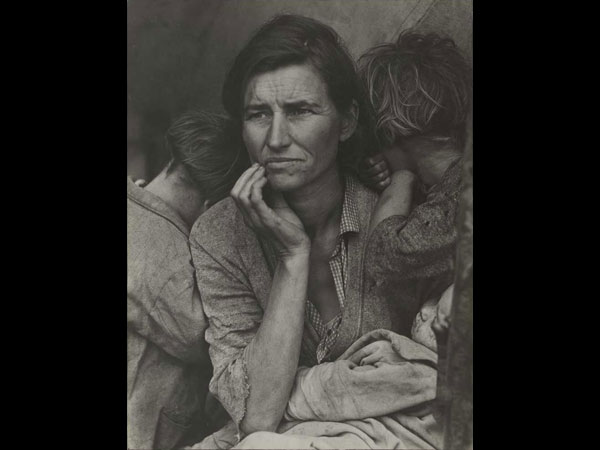

Dorothea Lange, CREDIT: Migrant Mother, Nipomo, Calif., 1936. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Purchase.One thing you can probably hang on Käsebier and Curtis is their romance with the face. In some of their portraits, the face (or the body) actually becomes the landscape. And this seems to be one of the most effective tropes of the Western portrait photograph. The close-up not only allows photographers to block out things in the environment—modern conveniences, other people—that might give the lie to whatever they're trying to convey, but also allows them to speak about the place through the face.

The prime example of the face as landscape is Dorothea Lange's iconic shot of the Depression, Migrant Mother. If you look at the outtakes from the shoot that yielded this famous shot, you'll see that only in Migrant Mother has the landscape been cropped completely. Almost the whole frame is taken up by the face, and the face reflects the state of the land—wrinkled, worried, dusty, spent.

In the show, you can see a related approach in Richard Avedon's devastating 1983 portrait of an unemployed blackjack dealer, whose very body has been marked and grooved by gambling. (And, to support the idea that face is place, the Avedon portrait is huge—more than four times the size of O'Sullivan's photo of Canyon de Chelly.)

-

Joel Sternfeld, CREDIT: After a Flash Flood, Rancho Mirage, Calif., 1979. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Acquired with matching funds from Shirley C. Burden and the National Endowment for the Arts © 2009 Joel Sternfeld.

Joel Sternfeld, CREDIT: After a Flash Flood, Rancho Mirage, Calif., 1979. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Acquired with matching funds from Shirley C. Burden and the National Endowment for the Arts © 2009 Joel Sternfeld.In the late 1950s, shortly after the publication of The Americans, Robert Frank's unsparing and understated book of photographs of American life at midcentury, irony began to creep into photographs of the American West. Where there's a gorgeous landscape, it's mocked in a billboard. When there's a placid house, it's at the tip of a landslide. Where there is a comfy interior, there's a power plant or a porn movie being shot just outside the window. The bigger the photograph, the less grand the subject.

Irony, by the way, seems to be the esthetic stance that the exhibition is most comfortable with. The key figures of the show—Robert Frank, Lee Friedlander, Edward Ruscha, Richard Prince, Cindy Sherman, Joel Sternfeld, and Larry Sultan—have deliberately deadpan styles and subjects that allow them to elude any accusations of unintentional fantasy making.

-

Garry Winogrand, CREDIT: New Mexico, 1957. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Purchase.

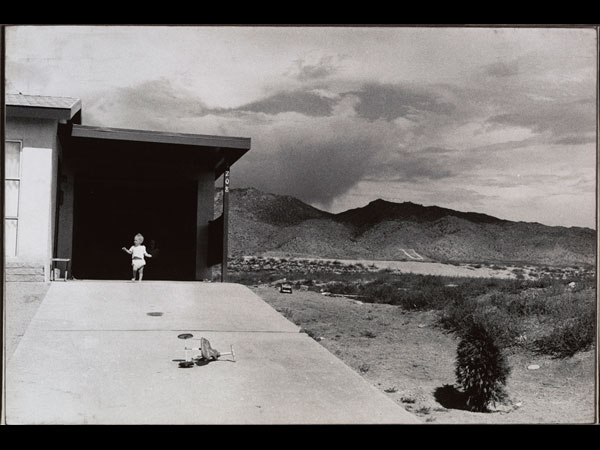

Garry Winogrand, CREDIT: New Mexico, 1957. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Purchase.One photograph I find difficult to place on the fantasy-reality-irony spectrum—which is therefore one of my favorites—is Garry Winogrand's 1957 picture of a suburban house in New Mexico. Like William Henry Jackson's picture of the Grand Canyon or Curtis' picture of Canyon de Chelly, it features grand nature and small humanity, and therefore invites an allegorical reading.

A toddler, all white and bright, emerges from the blackness of a carport and is about to walk the white plank of a sloped, concrete driveway, right into our arms. But it's not exactly a come-to-mama shot. Behind the suburban house are dark mountains and sagebrush and, above them, a brooding sky, about to pour its evil onto the world. And if all that doesn't get the poor sun-blinded kid, the toppled trike will.

OK, that's a little strong. But there's definitely a dark tale on the horizon. Something wicked—tornado, flash flood, depravity—is coming. And yet, despite the overload of foreboding, there's something aesthetically true about this picture. The blinding light is right. The contrast between dark garage and white driveway is right. The sense of the forlorn, spanking-new house, plunked into the middle of nowhere is right. And the Wizard of Oz sky is right, too. This picture, narrative and fantastic as it is, depicts something real in the Western landscape. And therefore it is, as far as I'm concerned, beyond the reach of the Marlboro Man.