How do you solve a problem like the suburbs? For one man in Arizona, it means creating an agricultural utopia, replete with picket fences and a community garden. He was inspired by one of our era’s most scathing critics of suburban sprawl: James Howard Kunstler. We’ll hear from both about what happens when you try to remedy what Kunstler calls “the greatest misallocation of resources in the history of the world.”

Download episode

Rebecca Sheir has been a host and reporter on All Things Considered, Morning Edition, Marketplace, Here and Now, The Splendid Table, and the Alaska Public Radio Network. Follow her on Twitter.

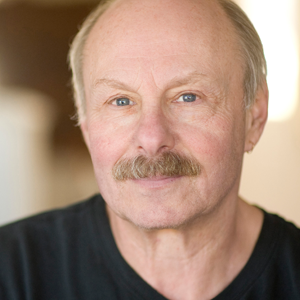

James Howard Kunstler is a novelist, playwright, and journalist. He has written numerous nonfiction books railing against suburban sprawl and its car-first model of development. Kunstler lives in Washington County, New York.

Rebecca Sheir: If you get on the massive six-lane highway heading out of downtown Phoenix, Arizona, you’ll drive past something you see in many parts of the state capital: sprawl. Phoenix is among the most sprawling cities in America, thanks to the population boom it’s seen since World War II. In 1940, it was home to 65,000 people. Today, it’s more like 1.5 million. And what was once agricultural land has largely given way to suburban housing developments. But a guy by the name of Joe Johnston—

Joe Johnston: When you drive down the street either you’re attracted to it or you don’t like it.

Sheir: He decided to buck that trend by creating a housing development of his own.

Johnston: The people that don’t like it would be the people that want large lots.

Sheir: And his development looks nothing like the juggernaut of strip malls, cul-de-sacs, and stucco-housing that define the suburban aesthetic.

Johnston: And then we’ll go look at the community garden. The community garden is where people are able to do their own gardening in a community setting. We will wander in there.

Sheir: Folksy and friendly in his wide-brimmed hat, Joe Johnston is a native of Gilbert: this suburb of Phoenix, 20-some miles east of downtown.

Johnston: When we moved here in ‘67, it was all dirt roads. The ditches were dirt, and so because dirt ditches are porous, there were a lot of trees all along here, cottonwood trees. There was one neighboring farm. The school I went to I graduated from a class of eight kids, all from a farming background. There was actually a guy in a covered wagon that would come down from the Superstition Mountains. Yeah. Very rustic.

Sheir: But now? Gilbert is the most densely populated incorporated town in the country.

Johnston: Starting around, uh, late ‘90s it became clear that development was coming our way in terms of subdivisions, growth, freeways, that sort of thing. Typically in our area people just scrape the land and then just build houses and they’re done with it. And the whole history goes away. Instead of just selling and going elsewhere, we decided to stay here and create what we thought would be the best stewardship of the farm. And so we decided to convert our family farm into a community.

Sheir: But not just any community, a kind of utopian community. One that revolves around living off the land. I’m Rebecca Sheir and from Slate magazine, this is Placemakers: stories about the spaces we inhabit, and the people who shape them. Today: How do you solve a problem like the suburbs? For Joe Johnston, it means creating your own utopia. And for a fellow we’ll meet a little later in the show—

James Howard Kunstler: 80 percent of everything ever built in America has been built in the last 50 years, and most of it is depressing, brutal, ugly, unhealthy and spiritually degrading.

Sheir:—it means completely rethinking the idea of urban development. We’ll talk with James Howard Kunstler, who’s been called “the world’s most outspoken critic of suburban sprawl,” about how we can save this country from, as he puts it:

Kunstler:—the greatest misallocation of resources in the history of the world.

Sheir: But first: back to Gilbert, Arizona, and Joe Johnston’s attempt to turn suburbia on its head.

Johnston: I thought: “OK, well, we’re going try to preserve urban agriculture. We want to create a good community.”

Sheir: A kind of utopia, if you will. So when it came time to name the place, he took the agricultural element:

Johnston: So, “agri”—

Sheir:—and the utopian aspect:

Johnston:—“topia.”

Sheir: And boom: Agritopia was born. Joe started building Agritopia in 2001, and in some respects, it looks like any other subdivision: row after row of houses, a school. But then you’ll see stuff that doesn’t necessarily scream “suburbia.” Like clusters of mailboxes, to encourage interaction; shallow front yards, so you can greet your neighbors on their wide front porch as you stroll by, pedestrian pathways everywhere, making it easier to take that stroll. Then you have something else decidedly unsuburban.

Johnston: Over here we got, uh, Brussels sprouts here, artichokes there.

Sheir: Garden plots that you can rent on the farm, which sits at the development’s center.

Johnston: Towards that big net you can see date palms down there.

Sheir: Residents of Agritopia raise more than 100 varieties of fruits and vegetables, many of which are sold to local restaurants.

Johnston: All these are public-access pathways, with grapes.

Sheir: Joe Johnston says the next step is to build something right next to Agritopia’s farm: a downtown. And where his family’s barn used to be, he’s creating a retail area called Bar None.

Johnston: The project that’s being built right now is Bar None, which would be a brewery, a winery, a salon, a florist, a woodworking shop, and letterpress paper and design.

Sheir: Then there are three-story apartments in the works—replete with connecting sky bridges. It’s a big change for Agritopia and its residents, people who were attracted to the idea of living in a quiet farming community. So you probably won’t be surprised to hear that when they held meetings about Joe’s plans, he got some pushback.

Johnston: Oh, you know, like “You’re just in it for the money,” “You’re ruining the neighborhood, this isn’t what Agritopia is supposed to be.” That kind of stuff, you know.

Sheir: But Joe actually seems fine with the conflict his changes have inspired.

Johnston: If you’re not doing something weird, and that some people don’t like, you’re probably not pushing the boundaries far enough.

Sheir: In the end, he says, just like his family farm had to change, Agritopia has to change, too.

Johnston: Some people will drive down the street and say, “Well, you know, it’s like Disneyland,” and this place has a certain order to it. But it’s not a sanitized village. You still have divorce, there’s suicide, there’s all that stuff. That doesn’t mean we shouldn’t try to create a beautiful environment. It just means this is the thing we took, and if you like it fine, if you don’t, you don’t have to live here, either.

Sheir: Agritopia is actually part of a growing movement of so-called agrihoods. The Urban Land Institute estimates that you can find about 200 of them across the country. And part of Joe’s inspiration for creating his own agrihood came from—

Kunstler (from TED Talk): The immersive ugliness of our everyday environments in America is entropy made visible.

Sheir:—this guy.

Kunstler: Mostly, I want to persuade you that we have to do better if we’re going to continue the project of civilization in America.

Sheir: His name is James Howard Kunstler. Here he is giving his 2004 TED Talk called “The Ghastly Tragedy of the Suburbs.”

Kunstler: There are a lot of ways you can describe this. You know, I like to call it “the national automobile slum.” You can call it suburban sprawl. I think it’s appropriate to call it the greatest misallocation of resources in the history of the world. You can call it a technosis externality clusterfuck. And it’s a tremendous problem for us.

Sheir: Kunstler is a novelist, and playwright, and journalist, and has written numerous nonfiction books railing against suburban sprawl and its car-first model of development. Books like The Geography of Nowhere: The Rise and Decline of America’s Man-Made Landscape and Home From Nowhere: Remaking Our Everyday World.

It was this last one that particularly inspired Joe Johnston to build Agritopia, out in Gilbert, Arizona. So, when I reached out to James Howard Kunstler for an interview not too long ago, I asked him what he thought of Joe Johnston’s endeavor.

Kunstler: Well, it sounds—it looks like he did a pretty good job of creating a new urbanist community. I’ve been associated with the new urbanist movement since its founding in 1993, and it was an attempt to reform the ways that we develop property in America, and to do it along the lines of more traditional town and cities and neighborhoods.

And my only problem with it was that it seemed like a good project in the wrong place. Phoenix is about the last place in America that I think has much of a future.

Sheir: Why do you say that?

Kunstler: Well, because facing the resource and capital scarcity problems as we do, Phoenix is a very unpropitious place to add more urban stuff to. You know, it’s a city that is going to really have to contract a lot, and I’m not even sure it’s going to be there in 50 years.

It has water problems. It’s not really a very good place for growing things without irrigation. And um, I have my doubts that it’s going to work out. You know, it’s also a place where if everybody doesn’t have air-conditioning, society there doesn’t really work. So I guess that’s my complaint about the project.

Sheir: Are you aware of any other developments inspired by your ideas or have developers and architects approached you, seeking your advice about projects?

Kunstler: Well, not my ideas per se. I really was a commentator on the scene when the new urbanist movement came along. You know, they were the people who really generated not just the ideas, but they dove into the dumpster of history, and they got back a lot of principle and methodology and skill for urban design that we had thrown in the garbage over the last, you know, half century in our effort to turn America into a driving utopia. And they did all the hard work. They figured out the ways to return to traditional town design and they did a great job.

There are a lot of projects that have been done by them around the country. Some of them are better than others. Many of them ran into problems with the permitting process where they had good ideas that were defeated by foolish municipal officials.

You know, for example, many of these projects included town centers that would allow people to live close to some kind of a store or, you know, a few retail things, and those were frequently shot down by the local municipal planners who refuse to change their zoning to allow it.

So, the new urbanists operated under a considerable burden of entrenched stupidity in the American planning system, you know, which includes a vast set of laws and regulations and zoning codes that have taken more than a half a century to put together and which, now burden us terribly.

There are several projects that are similar to this one in the sense that they were based around the idea of agriculture. And one of them is a project called Serenbe in Georgia. And that was designed by the leading architectural town planning firm of the new urbanism: Andres Duany and Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk, otherwise known as DPZ. And uh, as Andres quipped a few years ago, farming is the new golf. And that tells you a little bit about sort of what the demographic is that has been most involved in this.

Sheir: After the break, we’ll continue our conversation with James Howard Kunstler, and hear what today’s buildings have in common with video recorders, how the great American tragedy is all about boxes inside parking lots, and why “solutions” aren’t necessarily the answer to this whole mess.

Sheir: From Slate magazine, it’s Placemakers. I’m Rebecca Sheir. We started today’s show in Gilbert, Arizona, where a guy by the name of Joe Johnston wanted to build a different kind of housing development—one focused on living together, and living off the land. And so, about 15 years ago, he created “Agritopia.”

Joe took a lot of inspiration from James Howard Kunstler: a writer known for his scathing condemnation of our car-crazed culture, and the suburbs to which it’s given birth. Something else that makes Kunstler crazy? Zoning. Or, at least, the way we’ve been handling zoning for the past 70-some years. Here he is talking about it on his weekly podcast, which he calls “KunstlerCast.”

Kunstler: And it’s after World War II that we really start to get going on the refinements of zoning and we start to enter this really territory of the absurd. And among the things that we do is we decide that shopping is now classified as an obnoxious industrial activity that nobody should be allowed to live anywhere near.

Sheir: I live in Washington, D.C., and in my neighborhood it’s easy enough to walk out my door and do a little shopping. And more often than not, there are apartments right upstairs from the store, housing other people who can pop out their door and do exactly what I’m doing. And as a longtime city-dweller, I couldn’t imagine it any other way. But, says James Howard Kunstler, that’s not how officials following the old-school zoning codes see it.

Kunstler: The laws and codes that have already been set up create such immense obstacles to living that way, and they just go by the codes. They just sort of blindly follow the codes that have been put into place before them, and, now, they’re there and they have to follow them. For example, in much of America, if you want to open a retail store somewhere, you have to supply X number of parking spaces. Right? And if that’s the case, then just about every retail establishment is going to be some kind of a box in the middle of a parking lot. And if you have a whole town or city composed of boxes and parking lots, you’re not going to have really much of a walkable town. And that’s sort of the essence of the predicament. We’re blindly following these old codes, and it’s very difficult to reform them.

Sheir: Well, something you often talk about is the importance of having places worth caring about. So, what does a place need to have in order to make it worth caring about?

Kunstler: Well, I think mostly what it needs is the human scale. It needs to be a place that human bodies can move around in, and function in well according to what their neurology requires. And the trouble with the scale of suburbia, and indeed, with the scale of many of our contemporary cities, is that they impose a kind of a tyrannical and despotic scale on the human psyche, which is terribly punishing and makes it hard to function. Doesn’t give us any psychological rewards for being there. And history is going to see that it was a tremendous error to decide to live that way.

You know, I have a new theory of history, which is that things happen because they seem like a good idea at the time. And suburbia seemed like a good idea at the time, but it was a special time and place in history, with special dynamics. And now, we’re going to have to live with the consequences of that. And the consequences will be tragic.

Sheir: Well, if we want to build more places that are worth caring about, what does that involve? What does that look like in the design?

Kunstler: Building places that are worth living in and worth caring about require a certain attention to detail, and of a particular kind of detail that we have forgotten how to design and assemble. And that involves the relationship of the buildings to each other, the relationship of the buildings to the public space, which in America, comes mostly in the form of the street. Because it’s only the exceptional places in America that have the village square or the New England green. You know. The street is mostly the public realm of America. And we have to design these things so that they reward us.

For example: Many streets in American cities have been turned into mini-freeways by making them one-way streets and not allowing parallel parking on the curb. And that allows the cars to go much faster than they would ordinarily. I mean, that’s the whole point of turning them into one-way streets, is to maximize the traffic flow.

Well, in fact, the faster that every car goes on a street in downtown Minneapolis, the more unpleasant that street is going to be, and the more, over time, the buildings are going to turn their backs to that street, and people are going to shun those streets, and they won’t walk on them.

So, these are the kinds of things that we’ve been doing for decades. In our cities we put up these modernist office towers with blank walls on the ground floor that offer nothing for the passing pedestrian, that offer nothing either economically in terms of a commercial relationship between the people on the street and the building, and offer nothing even in terms of ornament, or something that would please the eye. In fact, all they do is sort of despotically tower over people and make them feel bad.

So, there are any number of design things and details that we could attend to that we just don’t because we have forgotten how to do these things.

Sheir: Well, while we’re talking about buildings, you gave a TED Talk, and you mentioned this civic building close to where you live in New York state. It’s boxy. It’s nondescript. I’m not even sure it has any windows. You were talking about the design firms who take on projects like this building and these last-minute meetings they have to nail things out. And you said this is what they’re thinking:

Kunstler (from TED Talk): Eight hours before deadline, four architects trying to get this building in on time, right? And they’re sitting there at the long boardroom table with all the drawings, and the renderings, and all the Chinese food caskets are lying on the table, and— I mean, what was the conversation that was going on there? [Laughter.] Because you know what the last word was, what the last sentence was of that meeting. It was: “Fuck it.”

Sheir: Do you really think developers just don’t care? Or do they know what they’re doing, and they just wanna maximize profits?

Kunstler: Oh, I think that there’s no question that they want to maximize profit. And frankly, you can’t blame people for doing that, but developers maximized profits in different eras of our history, and they managed to do it by putting up beautiful buildings.

Now, because we’ve been under the sway of about 90 years of dogmatic modernism, uh, it’s no longer acceptable to ornament a building, and we have lost the skills necessary to do it. So we’re basically just putting up buildings with blank walls that look like video recorders. You know, they have a hole, with a door that looks like the place that the input jack goes, and then they have a place, you know, where the loading dock is; it looks like where the cord for the speakers comes out, and they don’t give a fuck about the rest of the building. And that’s how we roll.

We’re living in a culture that doesn’t believe in decorating buildings, or proportioning them properly. And they don’t know how to do it anymore because they haven’t been doing it for, you know, the better part of the century.

Sheir: I was reading an interview you did with Rolling Stone. I used to write for Rolling Stone, actually. And the writer asked you, “Do you have a solution to our troubles?” And you said, “Solutions aren’t what you like talking about,” What should we talking about if not solutions?

Kunstler: What I also said was, um, I urge people not to think in terms of “solutions,” but in terms of intelligent responses to the quandaries and predicaments that we face. And there are intelligent responses that we can bring forth.

But when I hear the word “solution,” I always suspect that there’s a hidden agenda there. And the hidden agenda is: “Please, can you please tell us how we can keep on living exactly the way we’re living now, without having to really change our behavior very much?” And that’s sort of what’s going on in this country. And it’s not going to work. We’re going to have to change our behavior quite a bit.

And really, the general intelligent response to all this is that we’re going to have to downscale our activities and make them more local. And I think you can state categorically that most of the things that are now running at the giant scale are going to fail. They’re going to enter, you know, a zone of failure and they’re going to wobble and they’re going to go. You know, whether it’s mass motoring or Walmart shopping.

Sheir: But whatever happens, like you say in your TED Talk, the age of the 3,000-mileCaesar salad is coming to an end.

Kunstler: Yeah, I would say so. And it should be self-evident, but, you know, there are a lot of things that are obviously happening in our culture right now that we are just unable to pay attention to for one reason or another.

Sheir: Toward the end of my conversation with James Howard Kunstler, after all this biting talk about how grim the future is, and, really, the present, too, I asked him one last question—and I got quite the fired-up response.

Sheir: Can you give us some, hope here?

Kunstler: My job is not to be America’s therapist! I think that Americans are making a mistake to think that commentators like me should be therapist trying to make them feel better. It’s not about making you feel better. It’s about facing the facts of how we live in this country and what the conditions of life are and what the circumstances that are coming down on us represent. You know?

Life is tragic. If societies make poor decisions and make stupid decisions, they’re going to face that old banquet of consequences, and that’s where we’re at. So don’t expect people like me to be your therapist.

Sheir: The thing is, I don’t expect people like James Howard Kunstler to be America’s therapist. I’ve been reading commentary about Kunstler’s commentary, where people compare him to more of, like, a town crier, even a kind of Cassandra figure.

But Kunstler’s book, The Geography of Nowhere, the one that inspired Joe Johnston out in Gilbert, Arizona, to create Agritopia? It doesn’t just prophesize gloom-and-doom, and rant about the issues surrounding suburbia.

It talks about how we can remedy these issues. Like cutting down on commuting by car, taking steps to preserve our disappearing countryside, and, yes, designing places that are worth caring about.

One more thing we can do is something Kunstler mentioned at the end of his TED Talk back in 2004. And, really, it’s quite simple.

Kunstler (from TED Talk): Please, please, stop referring to yourselves as “consumers.” OK? Consumers are different than citizens. Consumers do not have obligations, responsibilities and duties to their fellow human beings. And as long as you’re using that word “consumer” in the public discussion, you will be degrading the quality of the discussion we’re having. And we’re going to continue being clueless going into this very difficult future that we face. So thank you very much. Please go out and do what you can to make this a land full of places that are worth caring about and a nation that will be worth defending.

Sheir: Placemakers is a production of Slate magazine and is produced by Mia Lobel, Dianna Douglas, and Michael Vuolo, and edited by Julia Barton. Our researcher is Matthew Schwartz. Eric Shimelonis does our mixing and musical scoring. Our theme was composed by Robin Hilton. Steve Lickteig is our executive producer. I’m Rebecca Sheir. Special thanks this week to Tarek Fouda for his reporting in Agritopia.

For more information about today’s show and other episodes of Placemakers, go to Slate.com/placemakers. You can drop us a line at placemakers@slate.com. You can follow us on Twitter; our handle is @SlatePlacemaker. And if you like what you’re hearing, please give us a review or rating on iTunes. It really does help.

Coming up next time on Placemakers: Social scientists say people in the United States are sorting themselves by political affiliation—Democrats on the coasts, Republicans in the southern and middle states. Now, followers of a third party say they want a home of their own, too.

Jason Sorens: This is a great day in the history of human freedom. It sounds grandiose, but I really believe it’s true. We are firing the starting gun on a mass migration of freedom lovers to New Hampshire.

Sheir: How Libertarians are taking the Granite State’s motto “live free or die” to a whole new level. That’s on the next episode of Placemakers.