Why Brutalist Architecture Is So Hard to Love

Courtesy of Lauren Manning/Flickr

Roman Mars’ podcast 99% Invisible covers design questions large and small, from his fascination with rebar to the history of slot machines to the great Los Angeles Red Car conspiracy. Here at The Eye, we cross-post new episodes and host excerpts from the 99% Invisible blog, which offers complementary visuals for each episode.

This week's edition—about Brutalism—can be played below. Or keep reading to learn more.

No matter which James Bond actor is your favorite, it’s undeniable that the Sean Connery films had the best villains. There’s Blofeld, who turned cat-stroking into a thing that supervillains do, and then there’s Goldfinger—Bond’s flashiest nemesis. Fun fact: The author of the James Bond books, Ian Fleming, named Goldfinger for a real person—an architect by the name of Erno Goldfinger, who made giant, hulking, austere concrete buildings. Fleming disliked these buildings so intensely that he immortalized their architect as a villain in pop culture.

And Fleming wasn’t the only critic. Goldfinger’s buildings were decreed “soulless.” Inhabitants claimed to suffer health problems and depression from spending time inside of them. Some of Goldfinger’s buildings were vacated because occupants found them so ugly. Yet, architects praised Goldfinger’s buildings. His Trellick Tower in London, completed in 1972 and once threatened with demolition, has been awarded landmark status.

This divide—this hatred from the public and love from designers and architects—tends to be the narrative around buildings like Goldfinger’s. Which is to say, gigantic, imposing buildings made of concrete.

Some people refer to this building style as Brutalist architecture, but Brutalism is a big, broad label that’s used inconsistently, and architects tend to disagree on a precise definition of the word. Furthermore, the word brutalism has intense connotations, even though it’s not actually related to brutality. The word originates from the French béton brut, which means raw concrete.

Lots of folks, beyond the creator of James Bond, love to hate these concrete buildings. Their aesthetic can conjure up associations with bomb shelters, the Soviet era, or developing-world construction. But as harsh as it may look, concrete is an utterly optimistic building material.

Around the 1920s, concrete was seen as being the material that would change the world. The material seemed boundless—readily available in vast quantities—and concrete sprang up everywhere, on bridges, tunnels, highways, sidewalks, and of course, massive buildings. Concrete has become the second-most consumed product in the world. The only thing we consume more of than concrete is water.

Concrete presented the most efficient way to house huge numbers of people, and governments all over the world loved it—particularly in Soviet Russia, but also later in Europe and North America.

Philosophically, concrete was seen as humble, capable, and honest—exposed in all its rough glory, not hiding behind any paint or layers. Concrete structures were erected around the globe as housing projects, courthouses, schools, churches, hospitals, and city halls.

In the late 1950s and early ’60s, Boston was plagued by a loss of manufacturing jobs and by white flight to the suburbs. For decades the Massachusetts capital had the highest property taxes in the nation and almost no new development. So Boston set an agenda to make the city great again by erecting big, soaring, modern buildings made of concrete. And, though some of these buildings were celebrated, others were despised.

Courtesy of Francisco Anzola/Flickr

When Boston City Hall was built in 1968, critics were put off by the concrete style. It was called “alienating” and “cold.” And since it was a government building, this criticism became impossible to remove from politics. Boston City Hall became a political pawn as mayors and city council members vied for public support with promises to tear it down.

But tearing down Boston City Hall has never come to pass. Doing so would take an incredible amount of effort and money. And so, government officials have largely chosen to ignore the building. This so-called active neglect happens with a lot of concrete buildings—they are intentionally unrenovated and uncared for. Which only makes the building more ugly, and then more hated, and then more ignored. It’s a vicious cycle wherein the public hate of a building feeds on itself.

When people built these mammoth concrete structures, no one really thought about maintenance, because they seemed indestructible. In the early days of concrete, people assumed it was an everlasting material that wouldn’t require any further attention. This has not proved true. But, it can be hard to tell when concrete needs repairing, because its decay is not visible on the surface. Concrete deteriorates chemically, from the inside out. Part of this has to do with the metal rebar reinforcements that help to hold up most concrete buildings. The rebar can rust, and the rust can eat away at the overall structure.

Courtesy of Richard E./Flickr

Tearing down massive concrete structures is costly and wasteful, but we can adapt these buildings to make them greener, more appealing places to be. And the best way to break the cycle of active neglect may be to love these concrete brutes in all their hulking glory. As with any art form—whether opera or painting or literature—the more you know about it the more you appreciate it. This is especially true of concrete buildings.

Architecture students appreciate them because they know that working with concrete requires great skill and finesse. Every little detail has to be calculated in advance because once the concrete is poured, there’s no going back to make adjustments.

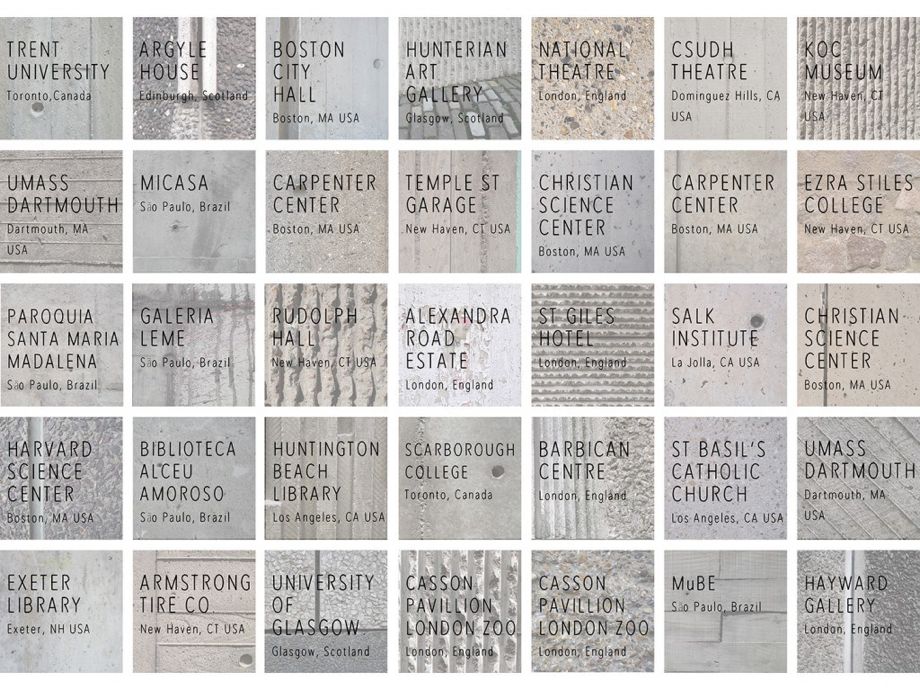

Aside from the interesting design challenges concrete poses, the material itself can be subtly beautiful. We call the city a “concrete jungle” to talk about the artificiality of the urban landscape, but concrete can actually be a very natural expression of the environment. What we think of as a homogenous substance is actually rich and diverse; concrete’s color and texture can be dictated by local climate, earth, and rock. Concrete can also be an expression of local style and custom. For example, British concrete has big, thick textured chunks of rock, while Japanese concrete is fine and smooth.

Courtesy of Sarah Briggs Ramsey*

But the beauty of concrete architecture might be the most apparent when you observe buildings like pieces of sculpture—without having to actually live and work in them. Which brings in concrete’s surprising ally: photography. Concrete looks good in photographs. It provides a neutral background to bring out people’s skin tones, or the color of their clothing. Fashion photographers discovered this first, but in recent years, pockets of the Internet started to appreciate these concrete buildings.

Photography is allowing a new audience to appreciate these buildings for their strong lines, crisp shadows, and increasingly, the idealism they embody. “[Concrete buildings] represent a set of ideas about the state of the world and what the future was imagined to be that we want to preserve,” says Adrian Forty, author of Concrete and Culture. “We should remember what people were thinking 50 years ago. If we tear these buildings down, we will lose all of that.”

Back in the 1960s, Victorian-style buildings were considered hideous and impossible to repair. We were tearing batches of Victorians down to erect big concrete buildings. But some Victorians were saved—and today, some of them are considered treasures. Concrete architecture now finds itself at an inflection point: too outdated to be modern, too young to be classic. And a small but growing band of architects, architecture enthusiasts, and preservationists would like us to just wait a bit and see. Maybe, with a little time, we’ll come around to love these hulking concrete brutes.

To learn more, check out the 99% Invisible post or listen to the show.

*Correction, Aug. 14, 2015: A photo credit on this post originally misspelled Sarah Briggs Ramsey’s first name.