How a Technology That Helped Settle the West Became Known as the “Devil’s Rope”

Courtesy of Gabriel Calderón/Flickr

Roman Mars’ podcast 99% Invisible covers design questions large and small, from his fascination with rebar to the history of slot machines to the great Los Angeles Red Car conspiracy. Here at The Eye, we cross-post new episodes and host excerpts from the 99% Invisible blog, which offers complementary visuals for each episode.

This week's edition—about barbed wire—can be played below. Or keep reading to learn more.

In the mid-1800s, not many (non-native) Americans had ever been west of the Mississippi. When Frederick Law Olmsted visited the West in the 1850s, he remarked that the plains looked like a sea of grasses that moved “in swells after a great storm.” Massive herds of buffalo wandered the plains. Cowboys shepherded cattle across long stretches of no-man’s land. It was truly the wild and unmanaged West, but it was all about to change, due, in large part, to one very simple invention that would come to be known as “the devil’s rope.”

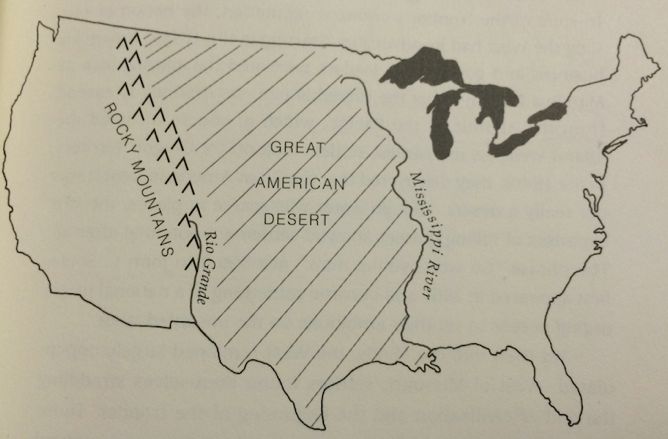

From the Colonial era through the early 19th century, the middle of the United States was populated mainly by Native Americans and a growing population of cowboys, or “cattlemen,” as they were often called. Most of the American West was divided into “territories” and, apart from Texas, most of the land was owned by the federal government. The middle swath of the country was so unexplored that it was often labeled on maps as “The Great American Desert.”

Courtesy of Joanne Liu

Then in the mid-1800s, a notion of manifest destiny swept the nation—the idea that the United States could, and should, span coast to coast. The U.S. government wanted farmers to move West, because farmers, unlike cattlemen, would establish communities and build permanent settlements. In 1862, President Lincoln signed the Homestead Act, offering 160 acres of free land to anyone who settled and farmed it for five years.

Photo by W.D. Johnson, 1897. Courtesy of Willard Drake Johnson/U.S. Geological Survey Photographic Library.

Would-be settlers started heading West in droves, but they quickly encountered a problem: fencing. In that great “sea of grasses,” there weren’t many trees to use for lumber. Although the land was fertile, there was no way to stop the many cattle from trampling and destroying crops.

Farmers tried using thick and thorny osage orange hedges for fencing, but they take about five years to grow, making them largely impractical.

Courtesy of Ted/Flickr

Settlers also tried smooth wire fencing, but the cattle could bust through it. People were getting frustrated; many abandoned their homesteads.

Fencing became a hot topic in newspapers, agricultural publications, and the government. The U.S. Department of Agriculture published a study in 1871 that found that it was impossible to settle the West because of a lack of fences.

But then came the solution: barbed wire.

Photo by Logan King. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

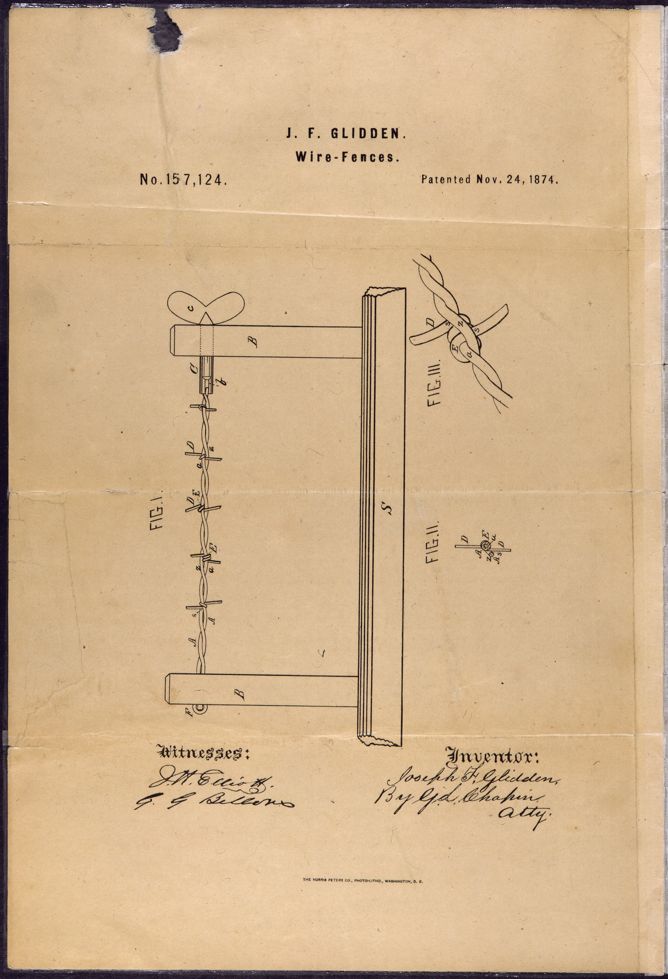

Many patent applications for variations of barbed-wire fences were filed around this time. But the barbed-wire design that ultimately won out and caught on was by Joseph Glidden. His design had sharp metal barbs twisted around a strand of smooth wire, with a second intertwined piece of wire so that the barbs couldn’t slide around.

Courtesy of National Archives and Records Administration/Wikimedia Commons

Glidden’s design took off, and by 1876, his company was producing nearly 3 million pounds of barbed wire annually.

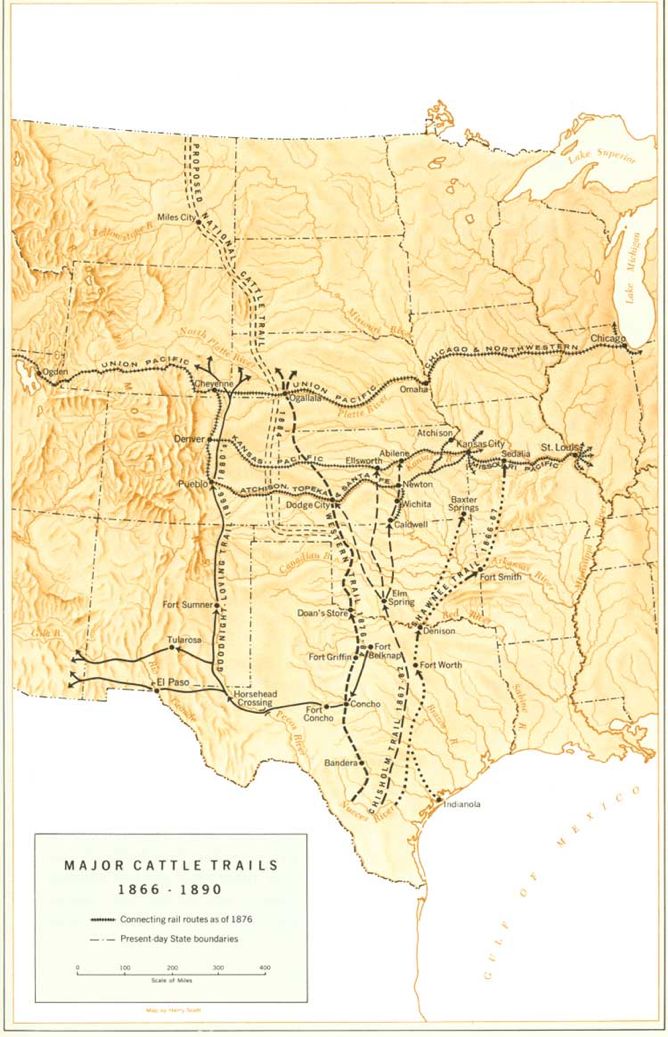

Before barbed wire divided up the West, cattlemen had mostly been watching and laughing as farmers struggled with their shrub fencing. Before the settlers arrived, the West operated under “the law of the open range.” Though it was never officially legislated, the law of the open range was respected and understood widely in the West. Cattlemen needed the land to be open so that cattle had access to grazing lands and water. This was especially true during the long-trail drives cowboys did to move cattle to larger cities where they’d be put on trains for export to the East Coast.

Courtesy of the National Park Service/Wikimedia Commons

Barbed-wire fences were in direct contradiction to the law of the open range and also could injure or maim cattle. The cattlemen weren’t happy, and relations became tense between farmers and cattlemen.

The musical Oklahoma! even has a song about this tension, “The Farmer and the Cowman”:

The chorus of the song implores all “territory folks” to stick together, but in reality cowboys and farmers wouldn’t become friends for a while. The cattlemen resented the farmers as they put up more and more fences. And that’s what lead to the fence-cutting wars.

In 1881, cattlemen started cutting down fences that farmers were putting around land that they didn’t have a rightful claim to. The cattlemen cut fences at night with masks on, and they formed fence-cutting gangs with names like the Owls, the Blue Devils, and the Land League. Eventually, the gangs would start cutting legally erected fences as well. Most of the damage thereof was in property value, but a few shooting deaths were attributed to this feud.

Eventually the federal government and the state of Texas intervened, and the fence cutting died down around 1885.

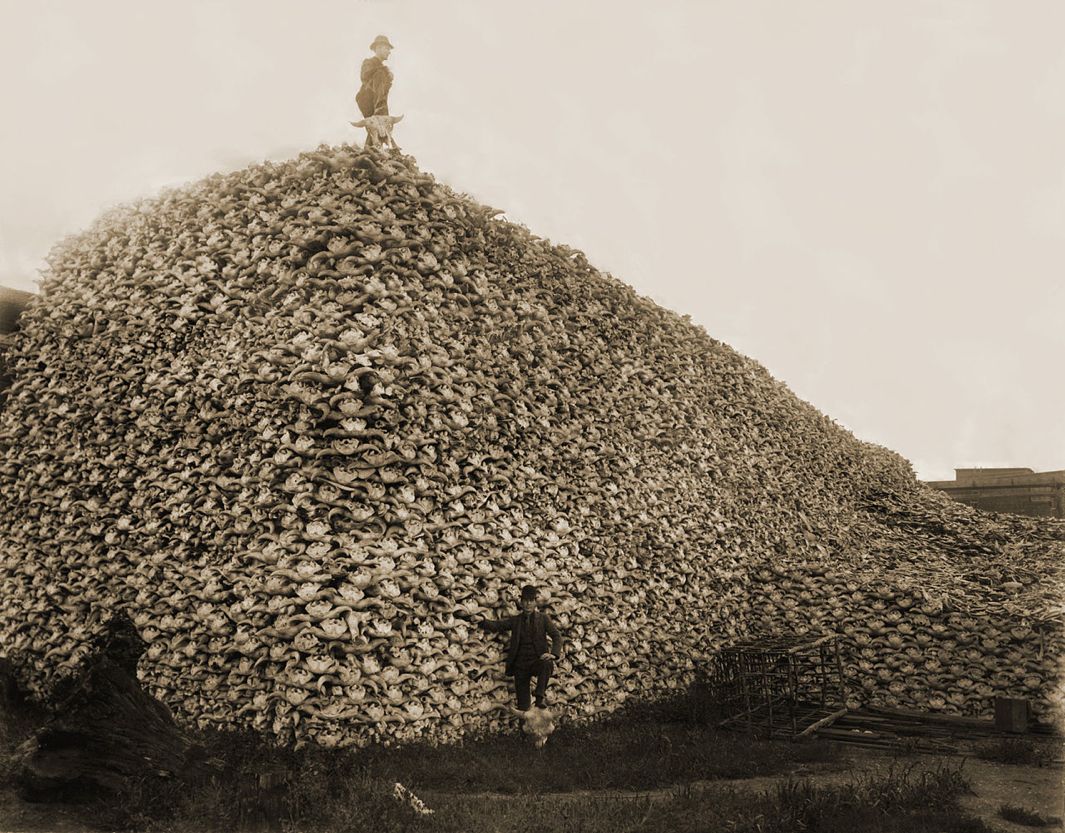

But the fencing off of the West didn’t just disrupt the cow population—it also had an effect on buffalo herds. During the 1800s, the buffalo that roamed the American West died off in huge numbers, in part because settlers were killing them for their hides, but also because barbed wire impeded the buffalo’s access to grazing lands and water.

Before white people lived in the West, there were an estimated 65 million buffalo roaming the plains. By the end of the century, there were fewer than 1,000.

Courtesy of Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library/Wikimedia Commons

The extinction of the buffalo in turn ruined an entire way of life for the Native American tribes that followed the migration of the buffalo. Native Americans ultimately came to refer to the wire as “the devil’s rope.”

By the end of the century, the West was covered in devil’s rope. And shortly thereafter, Europe would also be covered in it, but in a very different context. In World War I, barbed wire would become infamous in trench warfare; in World War II, it became the emblem of concentration camps.

Photo by A.F. Hager Jr./Marine Corps. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Barbed wire’s history has mostly been about control, possession, and separation but there is one instance where barbed wire was used not to separate us, but to connect us.

Right around the same time that barbed wire was invented, Alexander Graham Bell invented the telephone. At first, telephone companies were laying telephone wire in cities, but they weren’t interested in the rural market. But farmers also needed phones, which meant that they needed a network of wires to connect the farms.

Barbed wire fences could serve this purpose. The barbed wire couldn’t transmit a signal quite as clearly as a nice insulated copper wire, but for many years, it did the trick. A dozen or so farms might be connected on one system; for about $25, farmers could buy a kit to rig themselves into the network. In 1907 there were 18,000 independent telephone cooperatives serving nearly 1.5 million people. Because of this, farmers were some of the earliest adopters of telephone technology.

By the 1930s, the national Bell Telephone system had penetrated into the remote rural regions of the West and Midwest. Farmers no longer had to create their own telephone collectives, and barbed wire went back to doing what it does best: keeping us in, keeping us out.

To learn more, check out the 99% Invisible post or listen to the show.

99% Invisible is distributed by PRX.