How a French Opera and Sesame Street Inspired the Birth of the Philly Phanatic

Photo by Jim McIsaac/Getty Images

Roman Mars’ podcast 99% Invisible covers design questions large and small, from his fascination with rebar to the history of slot machines to the great Los Angeles Red Car conspiracy. Here at The Eye, we cross-post new episodes and host excerpts from the 99% Invisible blog, which offers complementary visuals for each episode.

This week's edition—about mascots—can be played below. Or keep reading to learn more.

As baseball fans probably know, the Washington Nationals used to be the Montreal Expos. When the team packed up and left Canada in 2005, it left behind its name logo, uniforms—and mascot, Youppi.

Photo by Matt Zambonin/Freestyle Photo/Getty Images

Youppi—French for “yippee” and stylized with an exclamation point—is a rotund, orange, furry, 6½-foot-tall Sasquatch-lumberjack creature, beloved by Québécois sports fans. Youppi became the first mascot to switch sports when he joined the Montreal Canadiens hockey team in 2005.

Furry, larger-than-life, foam-headed mascots may seem standard issue for sports teams now, but this is only a relatively recent phenomenon in the history of professional sports.

Hence, “mascotte” (or the anglicized “mascot”) came to mean a person or thing that brings good luck.

The idea of the mascot came to America by way of a popular French opera from the 1880s called La Mascotte. The opera is about a down-on-his-luck farmer who’s visited by a girl named Bettina; as soon as she appears, the farmer’s crops start doing well, and his life turns around. The word mascotte is a play on the French slang word masco, meaning “witch.”

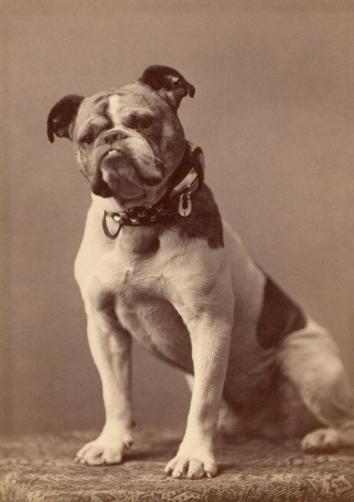

Courtesy of the Yale University Manuscripts and Archives Digital Images Database/Pach Brothers/Wikimedia Commons

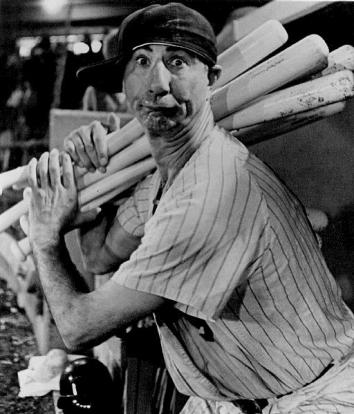

So at first, mascots were mostly passive agents that just stood around being lucky. That changed in 1944, at an exhibition game in Hawaii when Joe DiMaggio hit a massive home run off of a pitcher named Max Patkin.

Lucky mascots fit right in to the notoriously superstitious world of professional baseball. In the early days of mascots, if a player in a slump noticed a kid in the stands smiling at him before getting a base hit, he might give the kid tickets to the next game, just to have him there for luck. Anything (or anyone) that was around at the time of a team’s hot streak could be claimed as a mascot. Early examples include Harvard’s John the Orangeman, a bearded man who sold fruit during games, and Yale’s Handsome Dan, a bulldog that was walked onto the field before games.

Patkin snapped. He ran off the mound and chased after DiMaggio as he rounded the bases, mimicking his home run trot. The crowd loved it. After World War II ended, Patkin stopped being a pitcher and was hired by the Cleveland Indians to draw in and entertain crowds. Patkin was eventually dubbed the “Clown Prince of Baseball.”

Courtesy of Irv Nahan/Wikimedia Commons

The next step in the evolution of mascots was the San Diego Chicken.

In 1974, the San Diego radio station KGB-FM hired college student Ted Giannoulas to wear a chicken suit and do promotion for the station at Padres games.

The Padres were such a bad team that people started going just to see the chicken perform. Suddenly, the chicken was bigger than the radio station—and the team. Giannoulas was eventually fired from the radio station, so he got his own chicken costume and kept performing. The San Diego Chicken became a local icon even though he wasn’t an official team mascot.

The Philadelphia Phillies took notice and decided it wanted an upgrade from its mascots Phil and Phyllis—two figures in Colonial garb that didn’t do much besides decorate the outfield and appear on the field during the National Anthem.

Photo by Donald Miralle/Getty Images

The Phillies hired a designer named Bonnie Erickson, who had previously worked at the Children’s Television Workshop under Jim Henson. Erickson had created Miss Piggy and the Muppet Show hecklers Statler and Waldorf.

Erickson had also worked with Henson on making life-sized versions of the Sesame Street characters for their ice shows, so she knew how to make full-body costumes that people could perform and move in—a new concept when it came to mascots.

Erickson knew she needed to design a mascot that would be lovable even to the gruff Philadelphia sports fans. After all, this was a crowd that had pelted Santa Claus with snowballs during an Eagles game.

Photo by Mitchell Leff/Getty Images

So she came up with the Phillie Phanatic.

Every part of the Phanatic is like a master class in mascot design. For starters, he’s green, not the standard Phillies red, so he stands out in the crowd. The duck butt and pear-shaped body ensures that no matter how the performer moves in the costume, it’s funny. His eyes are low on his face, which makes him look childlike. He also comes with a backstory, which involves being from the Galapagos Islands.

The Phanatic is goofy and slightly aggressive. He’ll rub a bald guy’s head or rip the hat off of someone cheering for the wrong team. And usually, he gets away with it. Though he did once get pummeled by L.A. Dodgers coach Tommy Lasorda.

More and more teams wanted Phanatic-style mascots, so Erickson kept getting work. One of her clients was the Montreal Expos. Yes, Erickson is also the creator of Youppi—which, as it turned out, also gained an enemy in Lasorda (not to mention in Jimmy Fallon).

To learn more, check out the 99% Invisible post or listen to the show.

99% Invisible is distributed by PRX.