A Tale of Two Skyscrapers

Courtesy of Wikipedia Commons

The best design podcast around—and one of the best podcasts, period—is Roman Mars’ 99% Invisible. On it he covers design questions large and small, from his fascination with rebar to the history of slot machines to the great Los Angeles Red Car conspiracy. Here at The Eye, we cross-post his new episodes and host excerpts from the 99% Invisible blog, which offers complementary visuals for each episode.

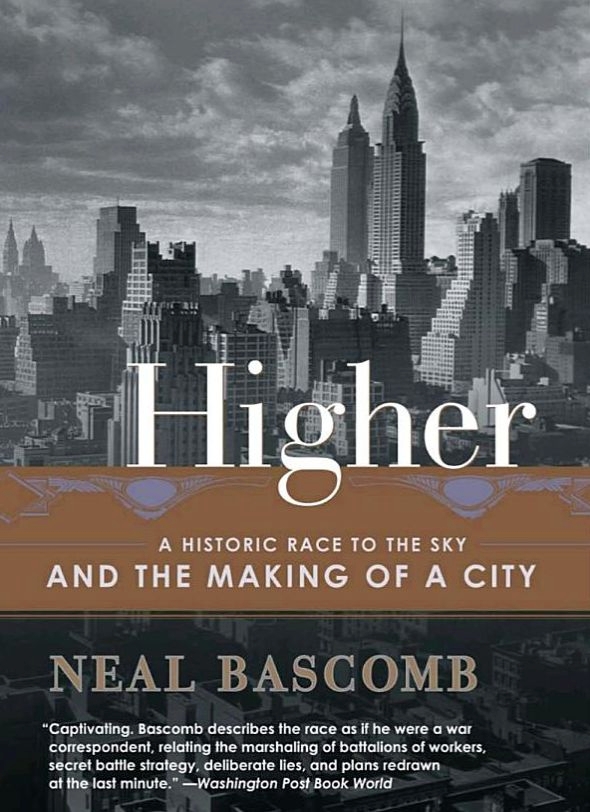

This week's edition—in which Neal Bascomb, author of Higher: A Historic Race to the Sky and the Making of a City and several other books, tells the story of an epic battle to dominate the NYC skyline—can be played below. Or keep reading to learn more.

Like the best of these stories, the two bitter rivals started out as best friends: William Van Alen and Craig Severance.

They were architects, and business partners. Van Alen was considered the artistic maverick and Severance the savvy businessman. It’s unclear why they broke up, but at some point, Severance decided he could do better on his own. The two parted ways and set up separate practices.

At the time of their breakup, New York City was undergoing a boom like nothing ever seen before. Massive wealth turned Manhattan into some of the most valuable property in human history. And when property gets valuable, we build up.

Late in 1928 Walter Chrysler, founder of the Chrysler car company, came to New York and bought a plot of land and decided to build what he referred to as “a monument to me.” Van Alen had already been working on plans for the previous owner of that plot and Chrysler decided to hire him to develop that plan into what would become the Chrysler Building. Walter Chrysler was a great fan of art and architecture and felt a real kinship with the Beaux Arts–trained William Van Alen.

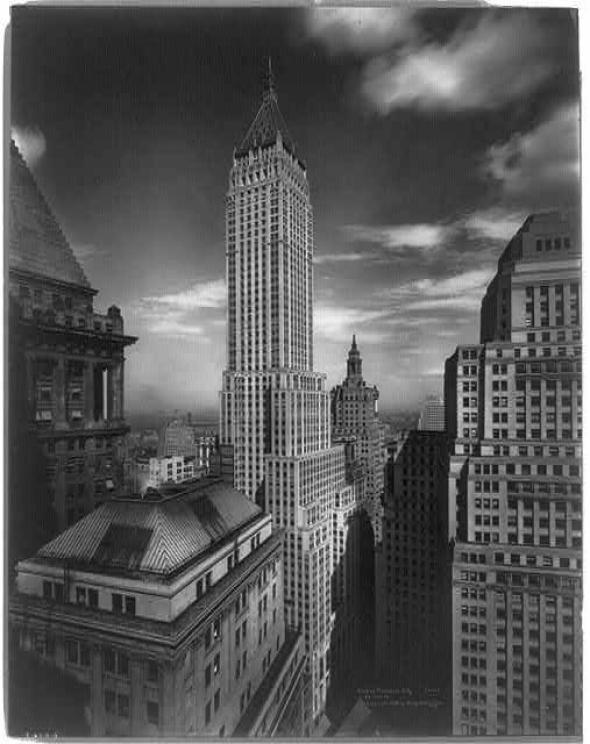

Meanwhile, downtown at 40 Wall St., Craig Severance was planning the Manhattan Co. Building. It was funded primarily by a young Wall Street hot shot named George Ohrstrom. The two towers had different goals. Severance’s building was being constructed to make money. The Chrysler Building was intended to be a monument to Chrysler, but it also aimed to be a beautiful and innovative structure.

Courtesy of Wikipedia Commons

At the time, Cass Gilbert’s Woolworth Building was the tallest building in New York City and both Van Alen and Severance intended to take its crown.

What followed was an epic back-and-forth struggle for the glory of ruling the New York City skyline.

The Manhattan Co. Building grew incrementally. As reports came in about the proposed height of the Chrysler Building, Severance simply kept adding as many floors as the foundation could handle. The Chrysler Building reached for the sky in two much more dramatic ways.

First, the dome of the tower was originally much more squat and rounded, but the urge to go higher made Van Alen stretch the arches to accommodate more floors. So that elegant, elongated dome that we love on the Chrysler Building was the result of this silly height race. But the sneaky masterstroke that ultimately led the Chrysler building to surpass the Manhattan Co. Building for good was the gleaming spire called the vertex. Van Alen had the 185-foot spire secretly constructed inside the building and on Oct. 23, 1929, the vertex emerged from the building’s core, “like a butterfly from its cocoon.” With that, the Chrysler Building became the tallest building in the world.

If the story stopped there you might think that Van Alen, the quintessential “architect as artist,” won the day. The Chrysler Building was the tallest structure in the world, and even though the design was panned originally, we all know that it eventually got its due. But the story did not end there. After all this hubbub of partner against partner, fighting for who would be the tallest, a mere 11 months later, the great Empire State Building was completed, and it became the tallest building in the world for nearly 40 years.

But what happened next was the real tragedy.

The lack of business acumen that probably contributed to Van Alen and Severance parting ways, came back to bite William Van Alen. He never actually had a contract with Walter Chrysler to design the Chrysler Building. After the building was completed, Chrysler refused to pay Van Alen the customary 6 percent fee, and the architect ended up suing the car-maker. Van Alen eventually got his money, but the lawsuit ruined his reputation. He never got a major commission again.

Courtesy of Wikipedia Commons

You probably know, and can clearly picture, the now-classic, art deco style of the Chrysler Building: the steel-clad arches, the sunburst triangular windows, the hood ornament-style eagles, and the hubcap friezes. (It was made for a car guy, after all.) But it’s doubtful you’ve even heard of the Manhattan Co. Building. This is probably because it’s now called 40 Wall Street or the Trump Building, but also because the design just never took hold in the public consciousness. This was not the case when the buildings were first completed. The Chrysler Building was universally panned and the Manhattan Co. Building got great reviews from architecture critics.

To learn more, check out the 99% Invisible post or listen to the show.

99% Invisible is distributed by PRX.