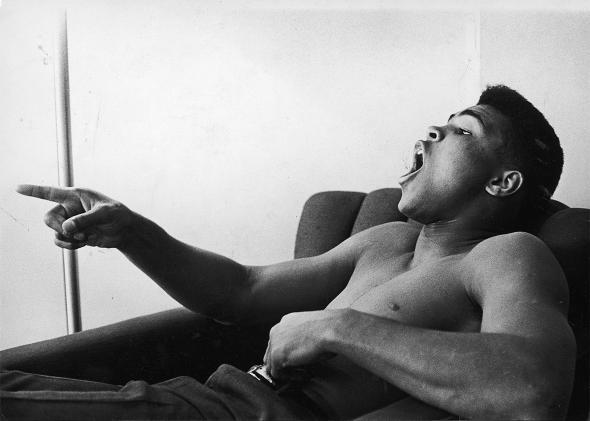

Muhammad Ali, who died Friday at 74, inspired glorious prose from a murderer’s row of marquee writers: Norman Mailer, Robert Lipsyte, and David Remnick, not to mention a generation of hip-hop artists. “He had been a splendidly plumed bird who wrote on the wind a singular kind of poetry of the body,” rhapsodized sports journalist Mark Kram in 1975. In 2006, ad guru George Lois gathered the mantling colors of the fighter’s verbal ephemera into Ali Rap, a book in which he proclaimed the boxer “the first heavyweight champion of rap.” Who could argue? With quicksilver rhyming dexterity and the braggadocio of a Homeric hero, Ali spoke the language of Compton long before Kendrick Lamar resurrected his floating butterfly as a symbol of black creative expression.

Boxing and talking were Ali’s one-two punch. About six months before his career skyrocketed with a world championship title—and before he converted to Islam and dropped his “slave name” Cassius Clay—he released an album of spoken word poetry, 1963’s I Am the Greatest. (His co-composer was the humorist Gary Belkin.) Featuring couplets like “Here I predict Mr. Liston’s dismemberment,/ I’ll hit him so hard, he’ll wonder where October and November went,” the record showcased Ali’s wit, whimsy, and irrepressible ego. The poet Marianne Moore penned the liner notes, observing, delightfully: “He fights and he writes. Is there something I have missed? He is a smiling pugilist.”

He fights and he writes. Moore’s chiming summary reminds me of a quote from Ali’s mother, Odessa, who once told Remnick:

He was always a talker. He tried to talk so hard when he was a baby. He used to jabber so, you know? And people’d laugh and he’d shake his face and jabber so fast. I don’t see how anybody could talk so fast, just like lightning.

Lightning was a recurring motif for Ali—in the ring, he boasted, “I done handcuffed lightning, thrown thunder in jail.” He didn’t just jabber; he jabbed. An athlete and a poet, he honed two modes of expression—physical and verbal—and applied to each a governing aesthetic defined by velocity and grace. Even in high school, Ali would preface his matches with a cocky couplet: “This guy must be done/ I’ll stop him in one.”

I’m not surprised that Ali charmed Moore, whose poetry reflects many of the same characteristics he displayed in competition: precision, delicacy, beauty, and speed. He was a Marianne Moore poem brought to life. “Neatness of finish!” she evangelized in “An Octopus.” Her liner notes praise up-and-comer Clay as “neat, spruce; debonair with manicure.”

When Ali first arrived on the boxing scene, he bemused audiences with his unconventional style—a distinct, dancelike mix of “circling, shuffling, hopping, dipping, ducking, feinting, jitterbugging.” The journalist A.J. Liebling hedged, “He was good to watch, but seemed to make only glancing contact.” Glancing contact is a perfect description for how Moore’s poetry relates to the world: She blended visual perceptiveness and fine-grained observation with a love of oddity, indirection, idiosyncrasy. She wrote poems about creatures—snails, pangolins, reindeer—whose glowing eccentricities became metaphors for individual artistic styles. It’s not hard to imagine Clay, the butterfly-bee, the “mouse” who could “outrun a horse,” as a Moore-ian invention, especially in the context of his own awareness of himself as spectacle. “Fighters are just brutes that come to entertain the rich white people,” Ali said in 1970, reflecting painfully on his status as a racialized wonder. “Beat up on each other and break each other’s noses, and bleed, and show off like two little monkeys for the crowd.”

But what about Ali’s linguistic pageantry, the words he used to talk about himself? As John Capouya recounted in a 2005 Sports Illustrated profile, he partially owed his “approach to flamboyant self-promotion” (as well as his interest in aesthetics) to the wrestler Gorgeous George Wagner. The 19-year-old Cassius Clay met Wagner in a locker room after the ebullient 46-year-old star had defeated his rival Freddie Blassie. “A lot of people will pay to see someone shut your mouth,” Wagner advised the future champion, explaining his own vow to “crawl across the ring and cut my hair off” if somehow Blassie beat him. “So keep on bragging, keep on sassing and always be outrageous.” (“I said, ‘This is a goooood idea!’ ” Ali told Capouya.)

You hear Gorgeous George in Ali’s cheerful bombastic self-mythologizing. (“Sooo pretty!” the elderly boxer marveled to Remnick, watching videos of himself fighting as a young man). Leibling called him “Mr. Swellhead Bigmouth Poet”; others referred to him as “Gaseous Cassius.” On June 4, 1975, Ali treated a class of freshly minted Harvard University grads to one of the shortest verses ever drafted, an ode to his greatness that reads, in its entirety: “Me? Whee!” Some of his other greatest hits include: “If you even dream of beating me, you’d better wake up and apologize” and “I’m so mean, I make medicine sick.”

As for “float like a butterfly, sting like a bee,” that iconic pair of similes reportedly came courtesy of Ali’s friend and assistant trainer Drew “Bundini” Brown (who copyrighted the lines). Brown joined the Greatest’s entourage at the recommendation of Sugar Ray Robinson: “I saw Muhammad on television reciting poetry in Greenwich Village … he needed somebody to watch over him, somebody to keep him happy and relaxed. I had just the guy.” The writer of Brown’s obituary didn’t specify which poets Ali invoked on the way to meeting a future soul mate—was it Gwendolyn Brooks, whose “We Real Cool” ripples beneath boasts like “I done handcuffed lightning”? Was it his old collaborator Marianne Moore? Either way, word and act, style and movement, fused beautifully in the life of the world’s best boxer. As both poet and athlete, Ali was more than gorgeous—he was a knockout.