Muhammad Ali was so much more than just a boxer. “I came to love Ali,” two-time foe Floyd Patterson told David Remnick for his book King of the World. “I came to see that I was a fighter and he was history.” Ali was a political, social, and religious activist, as divisive a figure as any celebrity during the turbulent 1960s. He was the godfather of trash talk. He was a master media manipulator. He was, simply, the most famous man on the planet. Then he became the public face of Parkinson’s and perhaps the most convincing argument for future generations of kids not to pursue boxing. He was, until the end on Friday night, as widely beloved a human as the world knew.

It can be hard for those of us who grew up after Ali’s career ended to appreciate his legacy, to understand just how large he was relative to life itself, to grasp how transcendent a figure he was before his communication skills diminished. Appreciating his skills as a boxer, on the other hand? That’s easy. All you need are YouTube and BoxRec to wrap your mind around what he could do and the unparalleled caliber of heavyweight opposition he did it against. Ali declared himself “the greatest of all time” before it was true. But then he made it true. He convinced us, and no heavyweight since has come close to unconvincing us.

Ali was a middleweight and a light heavyweight in the amateur ranks before he grew into his heavyweight frame (he didn’t crack 200 pounds until his 16th pro fight), and that informed his distinct fighting style. At heavyweight, he was a self-styled butterfly in a land of caterpillars. He bounced on his toes with the grace of a smaller man, circling, shuffling, hopping, dipping, ducking, feinting, jitterbugging. He pumped out jabs and combinations with a speed approximating his pugilistic heroes, welterweight/middleweight icon Sugar Ray Robinson and the less iconic but more directly influential light heavyweight Willie Pastrano. If his offense was unorthodox, his defense was downright absurd. Ali did so many things technically wrong but had the otherworldly reflexes to get away with all of it. He held his hands low, he pulled his head straight back exactly as every boxer is instructed not to do, but he made opponents miss by an inch or two and left them off balance and open for his counters.

His 1966 bout with Cleveland Williams is so widely cited as peak Ali that it’s clichéd to call it peak Ali, but damn if it isn’t boxing perfection.

They say the goal in boxing is to hit and not get hit. Williams hardly landed a punch in eight minutes. Ali hardly missed one. It was a full minute into the fight before Ali threw his first punch—such was his patience in measuring his man and his desire to show off his defensive mastery. Then the jabs unfurled. Then some hooks. Then a lead right. The hook off the jab, followed by an Ali Shuffle. Then more jabs, snapping back the head of the “Big Cat.”

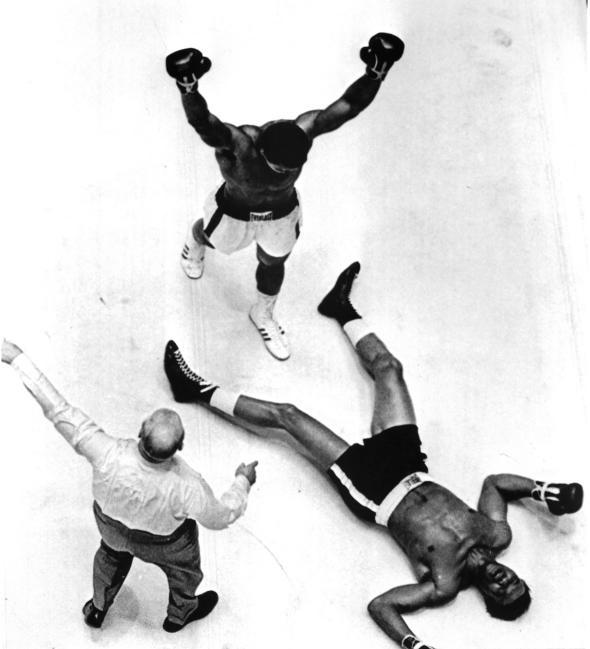

If you’re under the impression that Ali had no pop in his mitts, the brutalization that began in Round 2 will set you straight. Williams followed Ali around the ring hopelessly, handcuffed by the champion’s speed. With 40 seconds to go in the round, Williams walked directly into a blinding right hand, a clear-as-day version of the so-called “phantom punch” that felled Sonny Liston in 1965. Williams went down, then rose, but the fight was as good as over. An onslaught of rights and lefts produced knockdown No. 2 just a few seconds later. Just before the bell could save Williams, a searing left hook, left hook, right cross combination put him flat on his back. Instead of the bell saving him, it prolonged his beating, as Williams’ cornermen were allowed to enter the ring, walk him back to his stool, and get him ready to take more punishment. Round 3 began, and there were more shuffles, more combinations, and a straight right to put Williams down a fourth time. A right to the ear nearly knocked a bloody Williams down again, and finally, belatedly, referee Harry Kessler stopped the massacre after one minute and eight seconds of the third round.

Sure, it was a post-prime, made-to-order Williams on the receiving end of Ali’s brilliance. But still. What heavyweight before or since has ever put on a clinic quite like that?

The sports world should have seen several more years of that Ali, opening jaws and bloodying lips, but two fights later, his 1,314 days in exile began. The Ali we see in the Williams fight—this is the fighter we missed out on because he objected to the Vietnam War before it was fashionable to do so. After those 1,314 days, Ali was never the same in the ring. He was great, but in a different way. He couldn’t avoid as many of his opponents’ punches. So he sat down a little more on his own. When he couldn’t easily outbox them, he outfought ’em and outthought ’em. He forged a classic trilogy with Joe Frazier through will as much as skill, with ego grabbing hold of his steering wheel and anger pushing down on the gas pedal. He beat the monster that was 1974 George Foreman the only way he could have: with his brain. (And a little chin, heart, and balls mixed in.)

He became the only three-time lineal heavyweight champion at age 36 pretty much through muscle memory, craft, and desire.

Combine what made 1960s Ali great with what made 1970s Ali great, and you would have had the absolute perfect heavyweight. Sometime between March 22, 1967, and Oct. 26, 1970, he probably would have become that fighter.

But even without those 1,314 days of his absolute prime, Ali did enough to establish himself as what he said he was: the greatest. There’s only one other name even to consider for that distinction among heavyweights, and it’s a debate that raged for decades: Ali or Joe Louis?

To a certain extent, it’s a generational thing. But now the generation that grew up with Louis on the radio is mostly gone. Maybe it’s not fair to declare Ali the winner now, when memory of Louis has faded. But looking at it objectively, as a child of neither generation, it doesn’t seem such a hard choice. Louis had a longer uninterrupted reign, made more title defenses, was a far more destructive puncher. But look at Ali’s quality of opposition. He shook up the world against Liston, then did it again. He shocked the world against Foreman. He won two out of three against Frazier. Same against Ken Norton. He beat Patterson twice. The also-rans on Ali’s record—Jerry Quarry, Ron Lyle, Zora Folley, Oscar Bonavena, Bob Foster, Ernie Terrell—were as good as all but two or three opponents Louis beat during his historic reign. Match them up head to head, and the case for Ali is hard to deny: Ali fought and beat a few fighters who approximated the style and abilities of Louis; Louis never fought and beat anyone like Ali, because until Ali came along, there wasn’t anyone like Ali—at least not at heavyweight.

In my childhood and young adulthood, the conversation shifted, at least among casual boxing observers. It became a question of Ali vs. Mike Tyson. To those who truly understood the sport, it was almost laughable. And that’s no knock on Tyson, who was a force of nature during his brief prime. But the Ali we saw against Williams would have more or less toyed with Tyson, and the Ali who warred with Frazier would have found a way to win too. Tyson, as serious a boxing historian as you’ll find, has admitted as much, without hesitation. “Nobody beats Ali,” he said when asked if he’d have beaten him, prime against prime. And he explains that those who grew up in the ’80s and ’90s and perceived Tyson as the winner just because he hit harder and had bigger muscles let themselves be fooled by Ali’s physical appearance. “Ali is a fuckin’ animal,” Tyson said. “He looks more like a model than a fighter, but what he is, he’s like a Tyrannosaurus rex with a pretty face.”

There’s been a tendency over the last several decades to sugarcoat Ali’s flaws as a person—the unforgivable things he said to Frazier, the brutality he inflicted upon Patterson, the likelihood that some of his religious and political stands were as selfish as they were selfless. There’s a similar tendency to paint over his imperfections in the ring. He had major scares early in his career against Doug Jones and Henry Cooper. He won a few dubious decisions in his later years. He had no body-punching game whatsoever.

But Muhammad Ali never said he was perfect. He simply said he was the greatest. He was right. And you don’t need to have lived through his prime, his exile, or any of his comebacks to know it.