A version of this post originally appeared on the author’s blog, The Illiterate.

Remember last fall, when it looked like women, for the first time since the late ’90s, were taking over the pop charts? When female artists occupied the entire Top 5 and held onto it for almost two months? When more than half the records to enter the Top 10, for all of last year, were by women? You must, because everybody commented on it, and everybody was overjoyed, including me.

Those days are over. Almost a year later women not only don’t dominate the pop charts, but occupy a smaller share than they have since the early ’80s. Now that Taylor Swift’s 1989, Nicki Minaj’s The Pinkprint, and Meghan Trainor have begun to fade, the Top 10—and especially the No. 1 spot—has been dominated by men. Those women who have made it into the Top 10 are almost always in the company of men. The only solo women to enter the Top 10 in the first eight months of the year are Ellie Goulding (whose “Love Me Like You Do,” ironically enough, was boosted by its appearance on the soundtrack of Fifty Shades of Grey, a movie celebrating male domination) and Rachel Platten (whose “Fight Song” is about how she almost gave up on making it in the music industry). Every other record has either relegated the woman to a feature on a man’s record (Nicki Minaj and the uncredited Bebe Rexha on David Guetta’s “Hey Mama”), or presented a woman sharing space with a featured male (Natalie La Rose’s “Somebody,” featuring Jeremih, Selena Gomez’s “Good For You,” featuring A$AP Rocky, and the Rihanna/Kanye West/Paul McCartney collaboration “FourFiveSeconds”). And even though Taylor Swift’s “Bad Blood” would have made the Top 10 without the addition of Kendrick Lamar on the remix, he’s there all the same.

Here’s an even more depressing statistic: In the preceding paragraph, I’ve named every record featuring a woman’s voice to make the Top 10 in the first eight months of the year, a total of seven out of 23, or less than one-third. And it doesn’t look like the numbers are going to get much better. On this week’s Hot 100 (dated Sept. 12) there are only eight records featuring women in the entire Top 40, and all but one of those (Meek Mill’s “All Eyes On You,” featuring Nicki Minaj and Chris Brown) are either on their way down or have stalled well below the Top 10. The lower reaches of the chart are almost as bad, with only 15 records featuring women, less than one-third of which seem likely to break into the Top 50, two or three into the Top 20. The total number of records featuring women in the Hot 100 this week? Twenty-two, only 13 of which feature women on their own.

The year as a whole has been just as bad. Of the 255 records to debut on the Hot 100 through August, only 48 (19 percent) were by women on their own, while on another 32 (13 percent) they shared their record with a male singer or producer or provided support to one. This leaves the men, either solo or in combination, with 68 percent of the chart to themselves. Compare this to the same period last year, when the numbers, respectively, were 24 percent, 12 percent, and 64 percent (with 22 fewer records total). It’s worth noting that despite the strong female presence in the Top 10 near the end of 2014, the total number of women to make the chart actually dropped slightly in the second half of the year (and a large number of the records that did make it were by a single artist: Taylor Swift). The year ended with men claiming 65 percent of the chart, women 23 percent, and records featuring both at 12 percent.

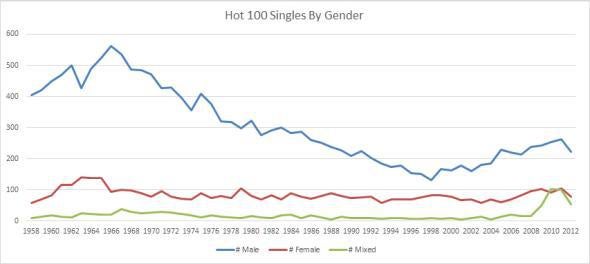

What may be even more troubling is that, historically, those numbers aren’t unusual. From 1958, when the Hot 100 first appeared, through 2013, solo women or female groups accounted for only 21 percent of entries, while sharing credit with men on another 5 percent. (Note: I’m still crunching numbers, but these figures, and the ones that follow, are a good rough percentage.) Features, of course, are responsible for the higher number of mixed-gender records we’ve seen over the last decade; before the early 2000s, they were fairly rare. The high point for women on the Hot 100 came in the late ’90s, when for five straight years they accounted for over 30 percent of charting records, peaking at 37 percent in 1998.

But percentages can be misleading. Those five years when women seemed to be gaining in percentage terms were also the years when the total number of records to make the chart was at its lowest. The figures for 1998, for instance, reflect a year in which only 223 records made the Hot 100, the smallest number ever. 83 tracks by women made the chart that year. In 2014, women generated an almost equal number of hits (82), but because there were nearly 140 more records overall (361), those tracks comprised only 23 percent of the total.

In fact, over its nearly 60 year history, the real number of records by women to chart on the Hot 100 each year has remained in roughly the same range, from the high 70s to the high 80s (the average is 86). There have been only nine years when women have put more than a hundred records on the chart, and all but three of those (1979, 2009, and 2011) came in the early and mid-sixties. The peak, not surprisingly, was 1963, the height of the girl group era, when nearly 140 records by women made the chart (out of 590, or 24 percent). The worst years—and this also isn’t much of a surprise, since they represented the peak of the white-guys-with-guitars era—were the late ’60s and early ’70s, when the percentage of women’s records was consistently in the mid-teens.

Looking at the numbers, you’d be excused for thinking there was a pre-set quota that determined how many records by women were allowed to make the Hot 100 each year. The chart below gives you an idea of how steady those numbers have been, even while the total number of records to make the chart consistently declined between the mid-’60s and the late-’90s. That decline affected men on the chart more than women, but that statistic has nothing to do with a drop in male popularity. Instead, it reflects changes in the industry itself—an industry largely run by and designed for male performers, producers, radio programmers, and executives.

Chart by the author

After the peak singles years of 1965 and 1966, commercial attention turned more and more toward albums, to the point where by the late ’90s physical singles were barely produced at all. Needless to say, most of the successful albums were by men, who took full advantage of the new paradigm and stressed the idea that albums were far more important culturally and artistically than singles. It wasn’t until 1999, after Billboard scrapped the rule requiring physical product in order for a single to be listed on the Hot 100, that the chart started to build momentum again, with the dawn of the digital era providing another important boost. Once more, however, that change in commercial impetus is reflected mostly in the number of singles by men that make the chart, a number which has risen with the tide over the last decade. Real numbers for records by women remain roughly the same. As I mentioned above, 2009 and 2011 were both good years for women, the best since the disco era, but those were also the years that fans of Taylor Swift regularly placed every record she released, including every album cut, on the chart. Since then, the numbers have tapered off and returned to where they have resided for the last 50-odd years.

This doesn’t mean that the chart achievements of last fall are meaningless. Maybe women in pop are moving into a new era where they will maintain a greater presence and influence, and the current lull is merely temporary. I’d like to think so. But it’s also possible that last fall was a statistical fluke, a confluence of major releases by musical 1 percenters that were guaranteed to sell and a handful of lucky novelties. If the popularity of EDM producers, so far nearly all men, continues to grow, things may get even worse, with more women’s voices being relegated to features. Looking at the total numbers, it’s obvious that both the industry and the audience aren’t making any more room for women than they ever have, and may be making less. The reasons for that, especially in the case of the audience, can’t be found in statistics. But at least the numbers can clarify what’s happening—or not happening—even if they can’t tell us why.