Top Right

Slate's list of the 25 Americans who combine inventiveness and practicality: our best real-world problem-solvers.

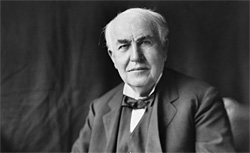

The oddest exhibit at the Henry Ford Museum in Dearborn, Mich., is this sealed glass test tube, which may or may not contain the dying breath of Thomas Alva Edison. According to some historians, when Edison was on his deathbed in 1931, Ford asked Charles Edison to capture his father's last exhalation and preserve it for him. The test tube is a legitimate Edison artifact, and Charles Edison appears to have sent it to Ford, but its contents are probably legend. Still, it gets at something profound and touching about the two most important Americans of their age. Ford was Edison's neighbor, friend, and former employee, yet he found Edison's gift for practical innovation so mysterious that he sought to hold the Wizard of Menlo Park's last breath for eternity, perhaps hoping to locate, in the nitrogen and carbon dioxide, the source of Edison's genius—as if the essential nature of America's greatest practical thinker could be captured and bottled and passed on to future generations.

If only it were that easy! Like few people before or since—though Ford himself is probably his closest competitor—Edison combined two radically different kinds of brilliance. Edison was of course one of the greatest inventors of his age, responsible for the phonograph, the stock ticker, the microphone used in telephones, and the practical incandescent light, among other world-changing devices. But Edison also put his inventions—as well as the inventions of others—to work like no one else in history. He founded the first commercial research laboratory in Menlo Park, N.J., turning ideas and experiments into valuable consumer products. Having perfected a practical light bulb, he then tried to make it widely useful by inventing the power distribution company. He popularized the Kinetoscope, the first commercially successful way to show motion pictures. The carbon microphone he invented in 1877—and then won a patent war over—was used in Bell telephones until the 1980s. Has any American generated so many new ideas, and put those ideas into practice, as Thomas Edison?

Ford couldn't successfully capture Edison's essence in a bottle. But 80 years later, we can pay it tribute. Slate has launched a project, Top Right, to identify the Americans who best share Edison's dual talents for inventiveness and practical thinking.

We're as enraptured as anyone by the utopian dreamers who promise fusion in a bathtub, a universal network of supertrains, nations remade by Twitter. But Slate is temperamentally inclined toward the here and now. Our focus in Top Right is on Americans who solve current problems.

Like a lot of others, we at Slate are very fond of the quadrant graph. (We don't need to tell you about it, right? See Steve Covey's Seven Habits of Highly Effective People or, for more pleasure, New York Magazine's sublime "Approval Matrix.") It occurred to us that the quadrant graph is an excellent way to represent how people (or institutions) balance innovation and pragmatism. The X-axis on our graph represents innovation, ranging from hopelessly pedestrian on the far left to mind-blowingly innovative on the far right. The Y-axis is pragmatism—you could think of it also as "effectiveness"—ranging from the hideously impractical at the bottom to the ruthlessly effective at the top.

The center point is where most of us live—competent, occasionally imaginative. The bottom left quadrant—dull and incompetent—is a hell of surly DMV clerks, Eastern European waiters, and CBS sitcom writers. The upper-left quadrant, practical but dull, is where you'll find capable managers, derivative thinkers, and shopping-mall developers. The bottom-right quadrant, innovative but impractical, is an elevated Blimp City financed through a flat tax and powered by solar panels.

And then there's the Top Right. It is here you find the world-changers, the people who combine inventiveness and pragmatism to solve problems that other people couldn't solve, or wouldn't solve, or hadn't even recognized.

Who are the 2011 Top Right? In our first edition of this list—the first of many, we hope—Slate is identifying 25 Americans, five in each of five categories: business, culture, technology, government, and design. We are revealing them gradually over five weeks, one group at a time. Today we unveil our five Top Right Americans in technology.

Obviously, with 25 people, this is not a comprehensive list of America's most capable innovators. There are great tech-heads left off of our technology Top Right, and fabulous business leaders left off that list. We're aiming for a thought-provoking group, a mix of knowns and unknowns, each of whom is exceptional in tackling, and solving, a knotty problem in a new way. The business group, for example, includes both Netflix impresario Reed Hastings, who has cracked the movie and TV business not once but twice, and Lady Gaga's business adviser Troy Carter, who has combined old marketing techniques and radically new ones to build Gaga's music, fashion, and media empire. (Please click here to see the rest of the list.)

You can help us improve Top Right in two ways. First, you should play with the Top Right widget at the bottom of each category. It shows the Top Right quadrant, along with the headshots of each of our Top Right winners. Use your mouse to place the five where you think they belong: Are they more innovative than practical? Does Hastings out-invent Carter? Which one is more practical? How do they compare with the other winners? After you make your choices, you can see how we ranked them and how other Slate readers ranked them.

Second, please tell us who we missed. Take to the comments section to nominate your own practical genius for next year's Top Right.