Who Is That Masked Man?

The wildly popular new Google tool that lets you wear a virtual mask—or hat or tiara—while you video-chat.

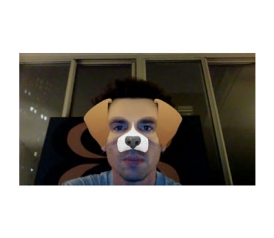

The Google+ “Hangouts” feature launched back in June 2011, providing a forum where up to 10 people (or, in rare cases, Muppets) can join together for a group video chat. In March of this year, Google debuted about 200 apps meant to enhance the Hangouts experience. There are tools devoted to collaborative business productivity and to multiplayer gaming. But, according to a Google spokesperson, the most popular Hangout app so far has been this one:

“Google Effects” lets you adorn your on-screen image with ridiculous accoutrements. Pirate hats, tiaras, monocles. When you play around with these props, their popularity at first seems intuitive. Pirate hats are badass. Tiaras are regal. Monocles lend the wearer an air of aristocratic refinement. The fluidity of the software itself is also stunning: The hats, glasses, and facial hair instantly scale to your face and track your image around the screen, retaining proper size and orientation as you lean forward and back or sway side to side.

This is no doubt a vital contribution to the science of virtual mustache wearing. And yes, part of the appeal here is the simple, silly fun. But I sense a more primal, more subconscious explanation for why these effects get so frequently incorporated into people’s chats: They help us overcome our innate distaste for video conversation.

The New York Times has reported that video chatting can be effective for targeted purposes such as remote music instruction or long-distance therapy sessions. (Although in the latter case, the mismatched eye contact—because patients and therapists gaze at their screens, not into their webcams—was a stumbling block.) As recently as 2010, though, according to a Pew study, only 23 percent of adult U.S. Internet users had ever tried a video call, conference, or chat. This, despite the wide availability of inexpensive webcams. You might figure teens would be early adopters, and in fact 95 percent of teens use the Internet, but a 2011 Pew survey found that only 37 percent of those online adolescents had participated in a single video chat. (Even in households with the highest income levels, the percentage was still less than half.) Video chatting has been around long enough that you might assume usage would have ramped up significantly by now, if word of mouth suggested that people actually enjoy the experience.

The thing is, most folks I know find video chats a drag. Sure, they are useful in select, specific circumstances. Terrific for letting your infant coo and burp at geographically distant relatives. Great for showing off the balcony view from your new apartment to a friend who hasn’t yet visited. Helpful in corporate contexts, when an actual face-to-face meeting isn’t possible but reading facial cues and body language might help seal the deal.

This last scenario, though, points up the central problem with video gabbing. The business negotiation is a highly formalized interaction, in which the players are acutely aware of their physical postures, expressions, and sartorial choices, and are careful to moderate them. Who wants to do that when you’re shooting the breeze with buddies? It’s exhausting.

The beauty of a phone call is that you can be in your underwear, flossing your teeth, and no one will know—so long as you floss noiselessly, which is totally doable with the more glidey brands of floss. You can also roll your eyes, let your jaw gape open in disbelief, and mime little yappy-yappy gestures with your hand when your interlocutor won’t shut up. Perhaps most important, you can productively multitask. Go ahead, click open those emails, watch those cat videos, and post that tweet—all while pretending to be an engaged, supportive listener. (It’s that much easier and less guilt-inducing to do all this while instant messaging instead of talking via phone. Which is why even the regular telephone call is falling out of favor.)

David Foster Wallace foresaw the video chat conundrum back in 1996, when his novel Infinite Jest envisioned the fictional future evolution of video chat etiquette. First, people bump up against the issue we’re already bumping up against: “Good old traditional audio-only phone conversations allowed you to presume that the person on the other end was paying complete attention to you while also permitting you not to have to pay anything even close to complete attention to her.” Next, folks become vain. They demand high-res, flattering digital images of themselves, which they can project as a substitute for their actual, just-awoken, pimpled mugs. (The less wealthy settle for custom-molded plastic masks that attach around the head with Velcro bands.) The final step in this process: the “Transmitted Tableaux,” which presents to the screen a still photo of an incredibly attractive person sitting in an imaginary, sumptuous setting—bearing almost zero relation to the actual video chatter and her actual living room. This allows us to once again send carefully chosen visual cues while flossing and making yappy-yappy motions in peace.

The early success of Google Effects suggests that DFW’s prediction of digitally augmented, reality-skirting video chats may in fact have been dead on. In my own experiments with Hangouts, I’ve found it strangely reassuring to have the power to decorate my face with a heavy beard, an eye patch, or a scuba mask and snorkel. It takes some of the pressure off, in a jokey way—lets me be less aware of the set of my mouth and the arch of my eyebrows. When I want to boost my comfort level even further, Google Effects lets me obscure the top half of my face entirely, overlaying the visage of a cartoon dog. Hey pal, talk to the friendly pooch—Seth is way too hungover to make his face look like he cares about you and your problems.

Why is it so soothing to wear a virtual puppy head and monocle? After all, I talk to people face to face every day, and I’m not driven to wearing a rubber Richard Nixon mask out in public. I think it’s because when you’re there in a room with a conversational partner it’s far more reflexive, far less of a chore, to monitor the physical signals you’re emanating. The level of remove implicit in staring into a teensy laptop webcam—instead of into a pair of real, glimmering, hopeful, fretful eyes—seems to add a few degrees of difficulty. Your facial bearing becomes more effortful. And it shows.

A 2011 Kickstarter project titled “Teleportraiture” hinted at this dynamic. Artist Janet Bruesselbach proposed to paint portraits of people via video chat. She theorized that the results would be different from those achieved in a traditional, live portrait sitting. “In video chat, interaction is very self-aware,” she wrote. “You find yourself having to alter your face from the way people look at computers to how they look at people. … This toggling between performing and concentrating means that, more often than not, the absent, concentrating expression of the computer user will be depicted.” (Click here and scroll down to see examples of her work.)

Where will Google Effects go next? So far, the effects at our disposal remain a bit limited. Clown hair, sunglasses, Dr. Seuss hat, and such. According to Google, the three most popular effects are a crown, a halo, and a pair of devil horns—which suggests that chatters are attempting to project value-laden notions of themselves. (I’m the king, I’m an angel, I’m mischievous.) A couple of other effects suggest further strides toward emotional signaling: A scatter of hearts that hovers above your head manages to project dopey affection, while a pair of upturned eyebrows accompanied by a giant, floating question mark lend the user a puzzled countenance. I’m intrigued by the idea of conveying more complex feelings with these effects, as adjuncts to my own facial expressions or even, in a pinch, as replacements.

Screengrab.

Of course, as always, the Japanese are way ahead of us when it comes to the machine-aided lifestyle. When I was at Comic-Con last month, I attended the launch party for Necomimi cat ears. These are robot ears on a headband, which—interpreting electrical signals sent from an earlobe clip and a forehead sensor—purport to communicate our internal moods via furry ear disposition. You’re excited? The ears perk up. You calm down? The ears sink and settle. As the website enthuses: “People think that our bodies have limitations, but just imagine if we had organs that don’t exist, and could control that new body?”

I got a freebie pair of these ears and, while I sort of enjoyed having new, twitchy appendages jutting out from my head, I wasn’t convinced the ear actions were closely corresponding to my nuanced emotional states. (Can ears signal regret? Schadenfreude? An intense need to pee?) Certainly my experience was nowhere near as awesome, or occasionally wistful, as that of the Japanese girl in this amazing promotional video:

Perhaps in the end Google Effects won’t just get more sophisticated but will move beyond video chats and bubble out into the real world. Then we’ll all start donning devil horns and floating question marks at cocktail parties. Could be socially helpful. Now, if you’ll excuse me, I need to go infiltrate that clique in the corner with the giant marijuana leaves bouncing from their headbands.