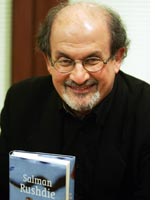

Arise, Sir Salman

Rushdie's knighthood reignites "Salmanophobia" at home and abroad.

"I am delighted for him," Ian McEwan said, when told that his friend and fellow novelist Salman Rushdie had been knighted. "He's a wonderful writer, and this sends a firm message to the book-burners and their appeasers." It would seem that the message was heard all too clearly, and not only in Iran and Pakistan.

This is the last honors list of Tony Blair's long premiership—and it's not Buckingham Palace but Downing Street, with some help from pompous committees of "the great and the good," deliberating who else might be considered great and good enough, that decides who will be honored. By awarding the knighthood, the outgoing prime minister has invited again the charge of "Islamophobia." Whatever that may mean, and however true the charge is, what we've certainly seen is a resurgence of Salmanophobia, that other powerful force of the age. The response to his honor in London, as well as in more distant capitals, reminds us that this man can unite Muslims, conservative nationalists, and the fashionable academic-intellectual left in hatred of him. It's an impressive feat.

Last Saturday was the queen's "official birthday," which, along with the New Year, is when assorted gongs are handed out, according to degree, to persons likely and unlikely. Those honored this time around included a former England cricket captain, Dame Edna (or at least Barry Humphries), rock singer Joe Cocker, and "the founders of the erotic lingerie line Agent Provocateur," along with Sir Salman.

He himself was "thrilled and humbled to receive this great honour, and am very grateful that my work has been recognised in this way," while others saw a belated endorsement or even recompense. Critic and former professor John Sutherland thought it was by way of apology from those who had not supported Rushdie clearly enough in his hour of need 18 years ago. "It's astonishing that Tony Blair, among others, has been so reluctant to be seen shaking Rushdie's hand, and here he is getting a knighthood from the Queen."

But there are still plenty of others who have no wish to shake Rushdie's hand, even figuratively. In the House of Islam, the reaction was all too predictable. "Salman Rushdie has turned into a hated corpse, which cannot be resurrected by any action," Mohammad Reza Bahonar told the parliament in Tehran, where the knighthood was angrily denounced as a further provocation. For good measure, one speaker called our dear queen "an old crone." Iran was, of course, the country where the fatwa was pronounced on Rushdie by the ayatollahs in 1989.

At points east, the knighthood was unanimously condemned by the parliament in Pakistan, our supposed ally in the "war on terror." Many Union Jacks were burned in cities there. (As with the innumerable Danish flags burned in Muslim countries when the cartoon affair broke out, one has to admire the entrepreneurial spirit that either stocks the offending flags in such numbers as a contingency for such events or runs them up at speed.)

In Islamabad, Robert Brinkley, the British representative, was summoned to be rebuked for the "utter lack of sensitivity" in knighting Rushdie. In turn, he expressed the British government's deep concern at the reported comment of religious affairs minister Mohammad Ejaz ul-Haq that the knighthood could justify suicide attacks. The minister later "clarified" this by saying that he meant it might seem to some suicide bombers a justification. So, that's all right, then.

All this was familiar from the eruption over Rushdie's novel The Satanic Verses 18 years ago, but the response in England was also painfully familiar. So far, there haven't been book burnings in the streets of London and Bradford, but there has been quite enough indignation.

When Lord Ahmed was made a member of the House of Lords by Blair, he was paraded as a moderate Muslim voice. He sounded only fairly moderate when he said on television that "Sir Salman" was an outrage against Islam and that the government should have knighted journalist Robert Fisk instead. (He really did say that.)

Eighteen years ago, Rushdie was much mocked—at a moment when he lived in danger of his life—by politicians and commentators on the right. Sure enough, in Tuesday's Daily Mail, Ruth Dudley Edwards returned to this theme by sharing her "prevailing thoughts" about Rushdie: "Self-important, pretentious, attention-seeking and ungrateful."

It would take a long essay to explain why Rushdie is so disliked by the right here, though it dates back a quarter-century to his days as self-appointed scourge of post-imperial British racism. Sutherland, his great champion, points out that The Satanic Verses was "extremely rude about England," which makes it the more striking that "he now has pledged himself in the personal service of the monarch!" (A rather literal-minded notion of what a knight is expected to do nowadays.)

The eruption of the Satanic Verses affair on St. Valentine's Day 1989 caught everyone by surprise, and indeed, as with the Danish cartoon affair, it was really factitious. It would never have happened if some zealot hadn't scoured a work of literary fiction previously unheard of in Tehran and thereby inflamed the passions of scores of millions who had not read it, and would never read it or any other novel.

Not that Rushdie was, or is, friendless. During the first drama, he was bravely defended by writers like Norman Mailer, who didn't know him, but still more by his group of friends, the most prominent literary gang in England: McEwan, Martin Amis, James Fenton, Christopher Hitchens. They have spoken out again, and, one could say, with the authority of renewed success: McEwan may shortly reach the top of the New York Times fiction best-seller list with his new novel On Chesil Beach, while Hitchens has already made it to the top of the nonfiction list with his atheistical polemic God Is Not Great. On Monday, Hitchens appeared on The Ten O'Clock News, the main BBC-TV news show, and gave a fine bulldog performance, saying that it was no business of these remote peoples to say who should be honored by the sovereign.

How much good this support will do Rushdie is another matter, and some of his defenders seem to have their own political agendas. Back in 1989, the xenophobic right that turned on Rushdie was personified by Norman Tebbit, one of Margaret Thatcher's chief lieutenants, who called Rushdie "an outstanding villain" and a man whose "public life has been a record of despicable acts of betrayal of his upbringing, religion, adopted home and nationality. Now he betrays even his own sneers at the British establishment."

But now there is a new group of ardent Anglo-neoconservative supporters of the American alliance, the Iraq war, and the crusade against "Islamofascism" who have rallied to Rushdie's cause. One of them is Daniel Finkelstein, comment editor and columnist at the Times, who is running a campaign to "Support Sir Salman." The decision to honor him was "bold and correct," says Finkelstein's manifesto: Apart from "the merit of his literary work, the author is a symbol of free speech."

That's what McEwan says as well, with his "firm message to the book-burners and their appeasers." Whether Rushdie really wants to be enlisted as a foot soldier—no, a knight is a member of the equestrian order—in this renewed clash of civilizations is another matter.