Is the Greatest Collection of Slave Narratives Tainted by Racism?

In the 1930s, the federal government sent (mostly white) interviewers to learn about slavery from former slaves. Can we trust the stories they brought back?

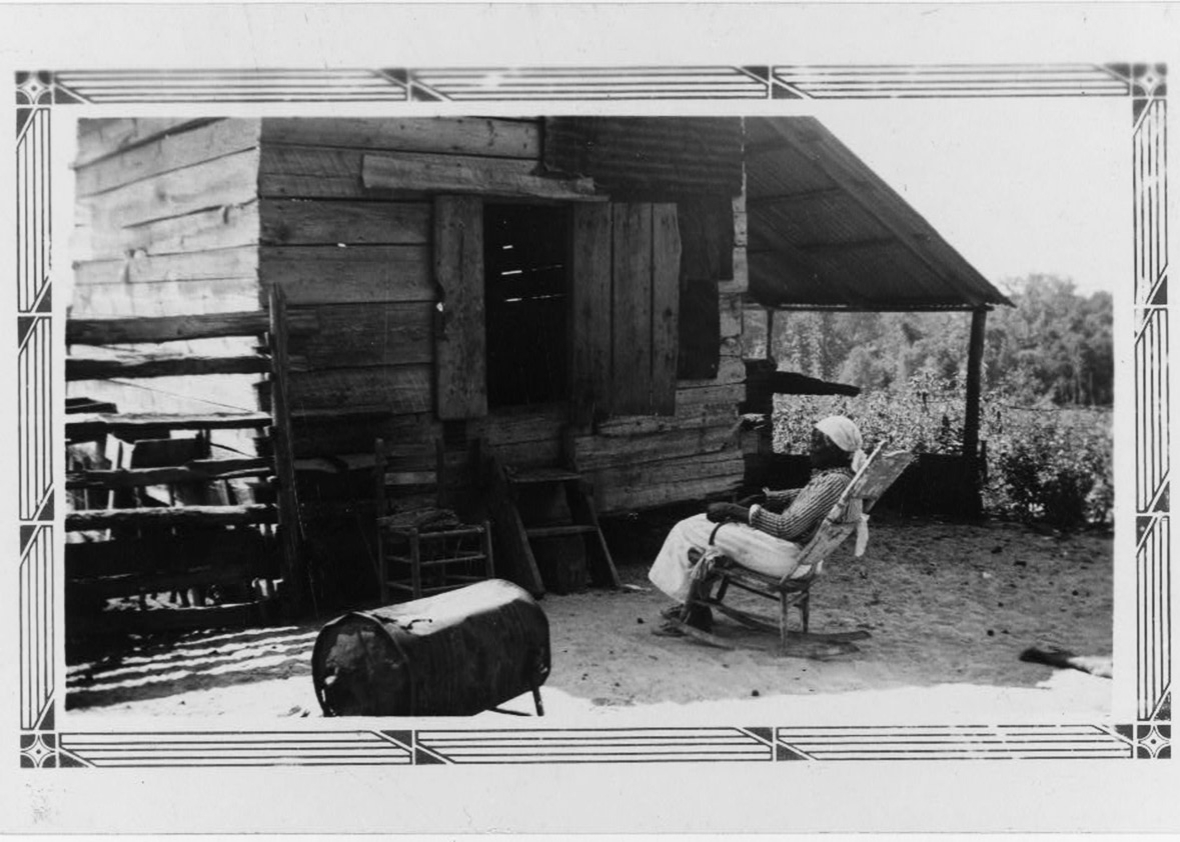

Library of Congress

When Josephine Anderson, a formerly enslaved Floridian, was visited by a white government interviewer in the fall of 1937, she told him a ghost story. Anderson described to Jules Frost a “white man” who walked alongside her as she traversed the railroad tracks one morning. “When I walk slow he walk slow, an when I stop, he stop, never oncet lookin roun,” the transcript of Anderson’s interview, rendered in dialect, reads. “My feets make a noise on de cinders tween de rails, but he doan make a mite o’ noise.” Anderson asked the man—who she declared to Frost to be a “hant”—to go away, by saying, “Lookee here, Mister, I jes an old colored woman, an I knows my place, an I wisht you wouldn’t walk wid me counta what folks might say.” The man went away, as bidden.

Why would Anderson tell a visiting researcher a ghost story? Was the tale a simple bit of folklore, passed on without motive? Or was it, as historian Catherine Stewart argues in her new book Long Past Slavery: Representing Race in the Federal Writers’ Project, a way for Anderson to comment on race relations in Jim Crow Florida—a means for a black interviewee to make an argument about the unwelcome presence of a white interviewer in her home, and to point out the danger she perceived in his presence, all while preserving a mask of civility and giving the interviewer what he had asked for? “While Federal Writers’ Project interviewers like Frost were engaged in writing down African American ghost stories,” Stewart writes, “former slaves such as Josephine Anderson were conjuring up tales about power and racial identities.”

One of our largest surviving bodies of testimony about slavery are the 2,300 Depression-era oral histories of elderly ex-slaves, gathered by workers like Frost, who were employed by the federal government as part of the Works Progress Administration. The collection has inspired methodological debate ever since the interviews became available to scholars in the middle of the last century. As many historians have noted, a deep power imbalance often complicated the relationship between white interviewers and black interviewees. In the most extreme situations, interviewers were descendants of the same families that had held interviewees as slaves. And in the Jim Crow South, the presence of any white interviewer could make the informants rightfully nervous. Records of the interviews show that some interviewers didn’t explain their presence, leaving the people whose houses they were visiting to arrive at their own conclusions about the visitors’ intentions.

Library of Congress

Despite all of these caveats, the narratives have had great value for historians of slavery. “Initially when scholars first started to really engage with this collection, around the 1960s and 1970s, it really helped them rewrite and correct the traditional understanding of the history of slavery, which had been dominated for many decades by apologists for slavery and defenders of the institution,” Stewart told me. While the nature of the evidence has lead some scholars to refrain from using it—historian Walter Johnson, in his book Soul by Soul: Life Inside the Antebellum Slave Market, wrote that he didn’t tap WPA narratives in part because he believed the circumstances of the interviews to be “inhibiting”—many have incorporated the narratives into their writing, albeit with proper caution.

In her book, which is a history of the making of the WPA narratives, Stewart chooses to look at the complete institutional and cultural context of their production. She finds that WPA interviewers and their editors wrangled over how much the ex-slave interviewees should be asked about slavery, how much they could be trusted to remember the events of slavery correctly, and how their observations should be presented. The story of the production of the WPA narratives is, in itself, a telling history of the state of race relations in the 1930s.

One of Stewart’s major findings: It mattered—a lot—who the interviewers were and who was editing the text they produced. At the federal level, Sterling A. Brown, a black poet and professor of English at Howard University, was appointed editor for Negro Affairs with the Federal Writers Project and given some power to comment on the black-related materials that the project produced. And there were scattered groups of black interviewers, in Virginia, Louisiana, and Florida, where segregated Negro Writers’ Units were briefly established, hiring out-of-work writers and other professionals—including, in Florida, trained anthropologist and writer Zora Neale Hurston.

This, Stewart argues, was revolutionary; at least for a short period of time, and in a scattered handful of places, there were black people building up a corpus of black history, and being paid by the federal government to do so. “This project was really sort of a step forward, for African-Americans to be invited to participate in the creation of the historical record of the African-American experience, when so often they had been left out of those conversations about the meaning of black identity, black citizenship, and slavery,” Stewart said, calling the project “radical.” Yet this was not a utopian advance by any means; the black interviewers were “the last hired and usually the first to be fired when budget cuts occurred,” Stewart writes, and “their presence did not guarantee that their voices would be recognized or heard.”

Brown, and the small groups of black interviewers in three states, was working within a larger white culture that wanted very particular things from black culture. During the 1920s and 1930s, white folklorists and writers observing the wave of black people moving north in the Great Migration wailed over the loss. Thomas Nelson Page wrote as early as 1904: “That the ‘old-time Negro’ is passing away is one of the common sayings all over the South … he will leave a gap which can hardly be filled.” The white rush to collect “pure, authentic” black expression, which hit the worlds of folklore, literature, and music in the interwar years, was actually a reflection of the racism of the time. Often, “pure and authentically black” came to mean Southern, rural, humble, superstitious, and uneducated.

Library of Congress

Nor was this kind of racist commodification confined to the South. Northern intelligentsia and literati were just as guilty. Stewart’s chapter on folklorist John Lomax, and the way he shaped and appropriated the music and career of Huddie Ledbetter, or Leadbelly, using what Stewart calls “stealth, coercion, and domination,” is infuriating. In marketing his music, Lomax “depicted Ledbetter as a black man of uncontrolled primitive impulses whose talent was harnessed only through his pledged loyalty to Lomax and his son Alan,” Stewart writes. Lomax copyrighted recordings of many of the folksongs he “found” in his travels in the South, profiting at the expense of the music’s performers and creators. With the exception of Brown, the white federal-level directors who shaped the project of gathering ex-slave narratives seemed to be looking for the equivalent of Leadbelly when evaluating prospective interviewees, seeking a “natural” or “primitive” type of black elder, who would offer diverting entertainment in the form of folk stories.

The 75th anniversary of the Civil War, celebrated during the Depression, also affected the climate that WPA-funded interviewers worked in. “For southern whites nostalgic for the antebellum era,” Stewart writes, mourning the loss of the “old-time negro” “was code for the disappearance of a generation who accepted their place at the bottom of the racial hierarchy.” White communities in the South held “Old Slave Days,” bringing in ex-slaves to be put on display. Stewart identifies several WPA interviewers who were members of the United Daughters of the Confederacy. The narratives these UDC interviewers collected, “featuring stories of slaves who preferred to remain in bondage out of love and fealty to former masters,” were of the type that were later circulated as curriculum in the Florida public school system, reinforcing myths about the Confederacy increasingly popular in the decade that produced Gone With the Wind.

Given this cultural climate, informants like Josephine Anderson found ways to satisfy white interviewers. “Ex-slaves were very skilled navigators of Southern mores and Southern customs, and speaking with whites,” Stewart told me. “Based upon leading questions, they could very often surmise what their listeners were hoping to hear, in terms of their testimony about slavery.” Zora Neale Hurston wrote about black strategies of conversational resistance in her 1935 book Mules and Men:

The Negro, in spite of his open-faced laughter, his seeming acquiescence, is particularly evasive. You see we are a polite people and we do not say to our questioner, “Get out of here!” We smile and tell him or her something that satisfies the white person because, knowing so little about us, he doesn’t know what he is missing. The Indian resists curiosity by a stony silence. The Negro offers a feather-bed resistance. That is, we let the probe enter, but it never comes out. It gets smothered under a lot of laughter and pleasantries.

Stewart observes that many narratives gathered by white interviewers for the WPA show evidence of this “feather-bed resistance.” Interviewees found ways to tell stories that white interlocutors might find objectionable, through signifying: a way of telling the truth indirectly, through symbolic expression, euphemism, humor, and metaphor.

Comparing ex-slave narratives gathered by black interviewers in Florida with those gathered by white interviewers in Georgia (where four employees of the FWP were also members of the United Daughters of the Confederacy), Stewart finds many instances of such hidden truths, recorded in collaboration with black interviewers and unwittingly by white interviewers. James Bolton, interviewed by a white worker in Athens, Georgia, told this story about whippings:

My employer—I means, my marster, never ’lowed no overseer to whup none of his niggers! Marster done all the whuppin’ on our plantation hisself. He never did make no big bruises and he never drawed no blood, but he sho’ could burn ’em up with that lash! Niggers on our plantation was whupped for laziness mostly. Next to that, whuppings was for steelin’ eggs and chickens. They fed us good and plenty but a nigger is jus’ bound to pick up chicken and eggs effen he kin, no matter how much he done eat! He jus’ can’t help it. Effen a nigger ain’s busy he gwine to git into mischief!

In this passage, Bolton wrapped a plain truth about a slaveholder’s violence—“he sho’ could burn ‘em up with that lash”—in humor and stereotype. The white listener, hoping to hear a story about paternalist slaveholders who cared for “their people,” would be attuned to the part of the testimony that praised the slaveholder for keeping the duty of whipping to himself, and might nod along with Bolton’s references to light-fingered slaves. Meanwhile, Bolton paints a picture of the slaveholder’s sadism, planted there inside the story, for people who were looking at the tale from a certain angle.

Library of Congress

In contrast to the kind of story Bolton told, interviewees speaking to black interviewers more commonly shared stories of cruelty and resistance and were open in describing the joy they felt when slavery ended. Speaking to Adella Dixon in Georgia, Berry Clay described his father’s conflicted reaction to being made into an overseer, which meant that he needed to punish his fellow slaves. “[Clay’s father] was too loyal to his color to assist in making their lives more unhappy,” Dixon reported Clay saying. “His method of carrying out orders and yet keeping a clear conscience was unique—the slave was taken to the woods where he was supposedly laid upon a log and severely beaten … [the slave would] stand to one side and … emit loud cries which were accompanied by hard blows on the log.”

While black interviewers recorded these kinds of testimonies about life in slavery, there was a conscious effort, at the federal level, to swing interviewers toward the folkloric and away from the controversial personal histories of enslavement. In 1937, Stewart finds, Lomax, then the WPA’s national editor on folkways and folk culture, redirected Ex-Slave Project interviewers to try to find out more about black folk customs and folk tales. While the information gleaned from this approach has been immensely useful for latter-day researchers trying to write histories of these aspects of black culture, Lomax privileged these stories over the ex-slaves’ assessments of slavery as an institution, preferring interviews about (as he wrote to the Georgia staff in directing their work) “the stories current at that time, the gossip of their associates, the small incidents of farm and home life, etc.”

White Americans of the 1930s were quite familiar with a particular genre of minstrelsy and plantation literature, like the Joel Chandler Harris “Uncle Remus” stories, which perpetuated stereotypes about black people while supposedly reporting on black folk culture. Under Lomax’s direction, white interviewers steeped in this ambient racism misjudged and misrepresented the stories their interviewees told them. “Interviewers unfamiliar with African American oral traditions often diminished their import,” Stewart writes, “representing the ex-slaves’ figurative language and metaphorical tales of the supernatural as a positivistic and literal embodiment of the naiveté and superstitious tendencies of black folk.” Interviewers were asked to write up their observations of the interviewees right after their encounters with the elderly informants and were asked to record whatever seemed “typical”—a directive, Stewart writes, that “invited observations that reinforced the most stereotypical images.”

The project leaders’ interest in “colorful” stories offered by black informants also resulted in the most distinctive characteristic of the narratives, to modern eyes: the painful dialect. Looking at correspondence between state and federal directors, Stewart traces the many decisions made about rendering black speech on the page. In correspondence between state and federal directors, Stewart found that white Southern directors spun out “their own racialized explanations for black folk speech. And they came up with a number of explanations for why they feel that ex-slave informants are slurring their words, or speaking differently, or leaving endings off certain words.” Stewart points out that in some instances these ways of speaking were “part of kind of a Southern regional dialect, much more than they are any kind of indication of a racialized identity.” But in their discussions about dialect, white personnel would hypothesize about the connection between this kind of speaking and a supposedly ingrained laziness.

Library of Congress

The oral histories black interviewers submitted differed in style as well as in content, rarely using dialect and taking care to show respect to their interviewees. In Florida, the members of the Negro Writers’ Unit introduced informants with descriptions meant to testify to their excellent memories (Rachel Austin’s interview with centenarian Luke Towns included this description: “Mr. Towns has been noted during his lifetime for having a remarkable memory and has many times publicly delivered orations from many of Shakespeare’s works”) and their persistence and character (Martin Richardson’s interview with Lindsey Moore was titled “An Ex-Slave Who Was Resourceful”). These stood in contrast to white interviewers’ introductions of ex-slaves, in which they often depicted their elderly informants as guileless objects of humor.

Black interviewers faced co-workers and supervisors who second-guessed their methods and their objectivity. They were accused of having “Negro bias”—a concept stemming from the racist idea that black people had an ingrained tendency toward emotionalism and also tended to lie and dissemble. “Whether whites attributed blacks’ tendency toward untruth to the forces of biology or environment,” Stewart writes, “their steadfast belief in this ‘racial’ characteristic made it very difficult for African Americans to be believed on any subject, least of all one as full of import as the institution of slavery.”

In Virginia, Eudora Ramsay Richardson, the state director, refused to believe a story that Roscoe Lewis, the director of that state’s Negro Writers Unit (and a professor at the Hampton Institute), recorded during an interview with ex-slave Henrietta King. King told Lewis that she had taken some candy at age 8 or 9 and that her slaveholder had punished her by holding her head under a rocking chair while she whipped her. The incident had resulted in a crushed jawbone and permanent disfigurement. (King said the violence gave her “a false face. …What chilluns laugh at an’ babies gits to cryin’ at when dey sees me.”) Disbelieving Lewis’ account, Richardson went to King’s home to fact-check it, thinking it was a “gross exaggeration.” She found instead that “[King] looks exactly as Mr. Lewis describes her and she told me, almost word for word the story that Mr. Lewis relates.”

Despite receiving confirmation in this particular case, Richardson continued to believe that Lewis was too credulous when it came to the stories of what she called “old Negros” who were “creatures of fine imagination who like to tell stories after a manner that will be pleasing to [an] audience.” It took a supposedly objective (white) editor like Richardson—who defended herself in letters to the federal directors of the project as “a liberal Southerner really!”—to see the truth of things. Richardson eventually had an all-white staff fact-check all of the material that the state’s black interviewers produced.

Brown, too, had his editorial suggestions challenged. Brown, Stewart writes, “tried to steer workers away from making bald assumptions about black character” based on their observations in the field. The Alabama state director (and member of the United Daughters of the Confederacy) Myrtle Miles complained to a higher-up after receiving such a critique from Brown: “It is still my feeling that the general criticism by your Negro editor is biased … I believe Alabamians understand the Alabama Negro and the general Negro situation in Alabama better than a critic whose life has been spent in another section of the country however studious, however learned he may be.”

Library of Congress

Whatever truths Brown and the black writers in the Negro Writers’ Units were able to slide into the WPA writings about slavery and discrimination, against the will of resistant gatekeepers like Miles and Richardson, were hard-won and risky. In the late 1930s, an anti-Roosevelt faction in Congress investigated the cultural projects of the WPA with an eye to defunding those that might be deemed “Communist.” The Federal Writers’ Project writings by black writers on racial discrimination, including Sterling Brown’s chapter in the WPA guide to Washington, D.C., on the history of racial discrimination in the city, came under scrutiny. When the Writers’ Project was turned over to state control as of 1939 as a result of these hearings, some state-published books (like The Negro in Virginia, which, Stewart writes, “was largely the result of the contributions of a talented Negro Writers’ Unit directed by Roscoe Lewis”) managed to retain a relatively honest point of view about slavery. But other states, like Georgia, when set free from federal oversight, published nostalgia-tinged histories full of myths about plantation life.

Together, the thousands of WPA-produced ex-slave narratives comprise one of the most fascinating sets of historical documents in American history. They’re wrapped in layers of complexity, telling stories about slavery, emancipation, Reconstruction, and the Depression. As Stewart’s book makes clear, some of the narratives, read at face value by wishfully thinking whites looking for historical absolution, have served to buttress Lost Cause mythology about good old “slavery times.”

Yet the body of stories also contains testimony like that given by Sam and Louisa Everett to black interviewer Pearl Randolph. The Everetts told Randolph what happened when news of emancipation reached the plantation where they were held. The slaveholder, “Big Jim,”

stood weeping on the piazza and cursing the fate that had been so cruel to him by robbing him of all his “niggers.” He inquired if any wanted to remain until all the crops were harvested and when no one consented to do so, he flew into a rage; seizing his pistol, he began firing into the crowd of frightened Negroes. Some were killed outright and others were maimed for life. Finally he was prevailed upon to stop. He then attempted to take his own life.

Such stories, Stewart points out, “provide a new way of interpreting stories of slaves who stayed on with their masters after emancipation” and who may have done so out of fear. Despite many obstacles, Randolph and other interviewers managed to get stories like the Everetts’ into the historical record. And that is valuable beyond measure.

More in Slate: Jamelle Bouie and I spoke with Henry Louis Gates about how historians came to value first-person evidence given by enslaved people in an episode of our History of American Slavery podcast series.