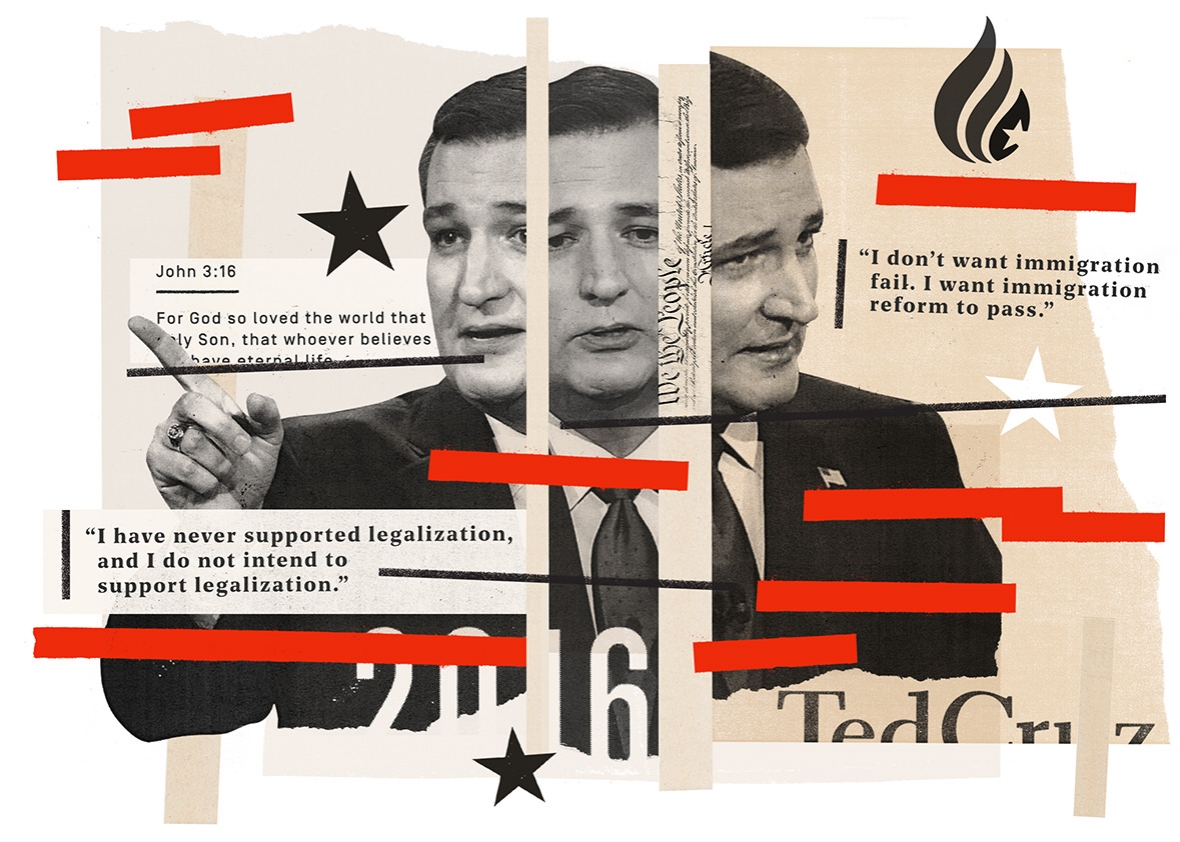

The Real Ted Cruz

I studied nearly every word the Texas senator uttered during the immigration showdown. He may be the most spectacular liar ever to run for president.

Illustration by Mike McQuade. Photos by Getty Images.

Ted Cruz is the only true conservative running for president. That’s the message of his campaign: He’s the only senator who stood and fought against amnesty, Obamacare, and Planned Parenthood. His finest hour was the defeat of immigration reform three years ago. Democrats wanted to give illegal immigrants a path to citizenship. Cruz said no. He took on the establishment and won.

It’s a good story, and the immigration fight tells us a lot about Cruz. But the fight didn’t happen the way he says it did. Cruz didn’t marshal the opposition or even take a firm stand. He’s a lawyer, not a leader. He chose his words exquisitely so that down the road—say, in a future campaign for president—he could position himself on either side of the immigration debate. And he delivered, with angelic piety, speeches that he now claims were lies.

Cruz told his version of the story last month at a campaign debate in Las Vegas. The “battle over amnesty,” he said, was “a time for choosing.” In that battle, Cruz stood with Sen. Jeff Sessions of Alabama to secure the border. Sen. Marco Rubio, Cruz’s Republican presidential rival, stood on the other side, colluding with Democrats to push “a massive amnesty plan.” “I have never supported legalization,” Cruz told the debate audience. In fact, he asserted, “I led the fight against [Rubio’s] legalization and amnesty.”

I’ve studied nearly every word Cruz uttered during the immigration showdown. I’ve put it together in a timeline that runs from January 2013, when Cruz was sworn in, to the end of June 2013, when the Senate passed the bill. The timeline, which you can read here, shreds Cruz’s mythical account. But it also paints an unsparing portrait of how Cruz—who has now clawed his way to the front of the Republican presidential pack—thinks and operates. Here’s what really happened and who Cruz really is.

The definitive timeline of what Ted Cruz said and did in the 2013 immigration debate.

In January 2013, when Cruz entered the Senate, he held the same view he espouses today. The proper way to deal with the millions of undocumented immigrants in this country, he said, was to “enforce the laws.” That meant barring them from employment and deporting them. Democrats wanted to offer these people a legal route to stay and earn U.S. citizenship. Cruz opposed that idea. Such a concession, he argued, would reward lawbreakers and punish honest people who were waiting to immigrate legally.

In late January, a bipartisan group of eight senators—four Democrats and four Republicans, including Rubio—issued an immigration reform proposal that included a path to citizenship. Cruz could have ruled that provision out, but he didn’t. For months, he expressed “deep concerns” about it but made no commitment. He cautioned that a path to citizenship would alienate many Republicans. But when reporters asked Cruz the yes-or-no question—“Would you vote against anything that has a path to citizenship?”—he refused to answer.

One plausible reason for Cruz’s reticence was that he wanted changes in immigration policy. He favored tighter borders, better enforcement, and an easier process for law-abiding applicants. He might be able to get those things in a deal. Furthermore, a path to citizenship was popular. In polls, more than 60 percent of Americans endorsed the idea, depending on how the question was phrased. Even self-identified Republicans supported it. So politics and policy told Cruz to keep his options open. But principle—fairness to legal immigrants and respect for the rule of law—stood in the way.

Cruz was in a tough spot. But there was a way out: Undocumented immigrants could be offered something less than citizenship. They could be given a path to “lawful permanent resident” status—a green card—that would let them live and work in the United States. They would be allowed to stay but not to vote.

Many Republicans liked this idea. It also scored well in polls. When Americans were asked to choose between creating a path to citizenship and creating a path to permanent residency, many preferred the latter. By offering green cards instead of deportation, conservatives could mobilize a national majority against citizenship.

Still, Cruz had a problem with the green-card idea. Under the proposed immigration framework, green cards would lead to citizenship. And that, Cruz explained, “worries me,” because “if we pass something that allows those here illegally to achieve citizenship, it means you’re a chump for having stayed in your own country and followed the rules.”

By late April, Cruz had worked out a solution. By permanently barring undocumented immigrants from citizenship, Congress could punish them and respect the priority of legal immigrants. In that context, as an inferior status, green cards were acceptable. At a Judiciary Committee hearing on April 22, 2013, Cruz urged his colleagues to pass legislation that foreclosed citizenship but would “ensure that we have workers who are here, out of the shadows, able to work legally.” Two days later, in an interview aired on CBS, he said, “There probably could be a compromise” on undocumented immigrants “if a path to citizenship was taken off the table.”

Photo By Bill Clark/CQ Roll Call via Getty Images

In May, Cruz spelled out his compromise. He offered an amendment that would deny citizenship to anyone who had entered the United States illegally. One stated purpose of the bill, Cruz noted, was “to provide a legal status for those who are here illegally, to be out of the shadows. This amendment would allow that to happen. But what it would do is remove the pathway to citizenship, so that there are real consequences that respect the rule of law and that treat legal immigrants with the fairness and respect they deserve.” Legal status without citizenship, Cruz argued, was “reform that a great many people across this country, both Republican and Democrat, would embrace.”

On May 21, the Judiciary Committee rejected Cruz’s amendment. But he didn’t give up. He reintroduced the amendment in the full Senate. In one venue after another—a forum at Princeton University, a speech on the Senate floor, an interview with the Washington Examiner—he made his case that the green-card compromise would grant “legal status” while still imposing “consequences.” Even after the Senate passed the bill without his amendment on June 27, Cruz continued to explain that he had offered to accept green cards, not citizenship, because “there needs to be some consequence for having broken the law.”

That’s a short version of what happened in 2013. Cruz moved on to other issues, and the bill never came up for a vote in the House. There’s more to the story, and we’ll get to that. But let’s consider what we can assess so far.

Three elements of Cruz’s current story about the immigration fight are clearly false. First, it’s not true that he embraced a “time for choosing.” Cruz postponed his immigration decision as long as possible. He refused to answer point-blank questions about whether he could accept a path to citizenship. When he finally came out against it, he did so in the context of offering a path to legal status. Even at the end of May 2013—four months after the immigration reform framework was unveiled, five weeks after the bill’s text was finalized, and a week after the Judiciary Committee passed it—Cruz still refused to say whether he would vote for the bill if it included his amendments.

Second, it’s not true that Cruz “led the fight” against amnesty. On April 21, 2013, three months after the path to citizenship was announced, Politico reported that Cruz still hadn’t “yet decided whether to become the face of the opposition.” The article noted that Cruz had “repeatedly avoided talking to reporters” about the bill and “was instead focused on fighting gun control legislation.” A year later, Politico detailed how House members had organized the opposition. The story said Cruz wasn’t even one of the most active senators. In November, PolitiFact, a project of the Tampa Bay Times, re-examined the record and “found no evidence that he [Cruz] should get credit for stopping the bill from reaching a vote in the House. During the summer of 2013, Cruz was one of many voices in the Senate opposed to the bill. It was House Republicans who blocked the bill, and they were already calling for its defeat.”

Third, it’s not quite true that Cruz fought “shoulder to shoulder with Jeff Sessions,” as Cruz puts it. It’s certainly not true that their positions were “identical.” Cruz and Sessions served together on the Judiciary Committee. Both men offered amendments to the bill. Sessions’ amendments proposed to restrict access to green cards. Cruz’s did not. This is important, because Cruz now claims that his alliance with Sessions proves that he never supported legal status for undocumented immigrants.

Photo by Jason Reed/Reuters

And that leads us to two more difficult questions. One is: Did Cruz support legalization? An ordinary person, after reading the narrative presented here, would probably say yes. But Cruz and his aides insist that he never explicitly embraced legalization. And they’re right.

No matter how carefully you study the timeline of Cruz’s statements, you’ll never catch the Texas senator endorsing—as opposed to conceding—legal status for undocumented immigrants. On May 21, 2013, he told the Judiciary Committee that his amendment would “allow that to happen.” On May 31, when he was asked whether he would “grant” green cards or “move” people from illegal to legal status, he replied: “That would be the effect of the amendment.” On June 11, he attributed legalization, under his amendment, to “the underlying bill.” Again and again, Cruz chose language that implied an offer of legal status but technically avoided responsibility for it.

Today, Cruz touts this record as proof of his innocence. To understand why, you have to watch his interview with Greta Van Susteren on Dec. 18, three days after the Las Vegas debate. Van Susteren reads from a letter issued by Cruz and three other senators on June 4, 2013. The letter faults the Judiciary Committee for rejecting “an amendment (Cruz 3) that would have allowed immigrants here illegally to obtain legal status—to come out of the shadows and work legally—but not to be eligible for citizenship.” Van Susteren, like any normal person, reads this sentence as a tacit endorsement of legalization. But Cruz points out that allow doesn’t necessarily mean support. He insists: “The letter says Rubio’s bill gives them legal status. It doesn’t say my amendment gives them legal status.”

Cruz thinks this distinction vindicates him. He proudly tells Van Susteren: “Greta, truth matters. I have never once supported legalization.” But what’s striking in the interview, in the letter, and throughout Cruz’s statements in 2013 and in 2015 is how carefully he parses words such as supported, legalization, and truth. Cruz doesn’t think like a normal person. He thinks like a lawyer. For him, truth isn’t a matter of plain meaning. It’s a matter of technicalities.

That’s why nobody can prove Cruz endorsed legalization in 2013. Like a crime scene without fingerprints, Cruz’s verbal record is a work of art. On Dec. 15, the Washington Post’s Fact Checker, unable to pass judgment on Cruz’s account of the 2013 fight, surrendered to his ingenuity, explaining: “Cruz positioned himself in a way so that he would appear pro-legalization if an immigration overhaul passed—or appear anti-legalization if hard-liner stances became more acceptable.”

But Cruz doesn’t just deny that he supported legalization. He denies that his amendments were serious at all. He now claims that every measure he proposed in 2013—to tighten border security, streamline legal immigration, and close the path to citizenship—was a ploy to sabotage the bill.

To appreciate the audacity of this claim, you have to watch the speeches Cruz delivered three years ago. At a Judiciary Committee hearing on May 21, 2013, Cruz pleaded for “bipartisan agreement and compromise,” declaring, “I don’t want immigration reform to fail. I want immigration reform to pass.” On May 29, he assured Washington Examiner reporter Byron York, “My objective was not to kill immigration reform, but it was to amend the Gang of Eight bill so that it actually solves the problem.” And on May 31 at Princeton, Cruz told his former professor, Robert George: “I believe if the amendments I introduced were adopted, that the bill would pass. And my effort in introducing them was to find a solution that reflected common ground and that fixed the problem.”

Now Cruz says he was faking it the whole time. He says everyone knew he was just trying to sabotage the bill. But that’s not true. Many conservatives believed him. York, in his write-up of the May 29, 2013, interview, took Cruz at his word. George, in his public conversation with Cruz, also took the senator seriously. And in a Fox News interview on Dec. 16, just after the Las Vegas debate, Bret Baier made clear that he wasn’t in on the joke, either:

Baier: It sounded like you wanted the bill to pass.

Cruz: Of course I wanted the bill to pass—my amendment to pass. What my amendment did—

Baier: You said the bill.

Cruz: —is take citizenship off the table. But it doesn’t mean—it doesn’t mean that I supported the other aspects of the bill, which was a terrible bill. And, Bret, you’ve been around Washington long enough. You know how to defeat bad legislation, which is what that amendment did …

Van Susteren, in her conversation with Cruz two days later, seemed baffled:

Van Susteren: You are now saying that the whole purpose of the amendment back in 2013, that you put on, was a poisoned pill. It was meant and designed to kill the whole bill.

Cruz: And it succeeded. …

Van Susteren: And your strategy, just so we’re clear—your strategy was to put this poisoned-pill amendment—

Cruz: That was actually five amendments that were all designed to defeat this.

These people—York, George, Baier, Van Susteren—aren’t stupid. They work in the thick of conservative politics. What confounds their ability to understand Cruz isn’t ideology or intelligence. It’s artifice. Normal people can’t sustain a façade of earnestness for months. Normal people don’t lecture others about good faith while lying and conspiring. To live a sane life, you have to assume that the people with whom you interact are, to some extent, real. York, George, Baier, and Van Susteren are normal. Cruz is not.

If Cruz was faking it in 2013, consider the extent of his deceit. He didn’t just put on performances for his colleagues in the committee and on the Senate floor. He requested an interview with a conservative publication, ostensibly to clear the record, and lied to its reporter. He went to his alma mater and feigned sincerity to his mentor in front of an audience of students. And he didn’t stop when the Senate passed the bill. In an interview with the Examiner on July 1, 2013, and again in an interview with the Texas Tribune on Aug. 21, 2013, Cruz cited his legalization offer as evidence that he was willing to compromise.

Was the whole thing a ruse? Only Cruz knows. But the rest of us can draw a few conclusions. First, Cruz is a spectacular liar. If he wasn’t lying about his motives in 2013, he’s lying about them now. That’s not speculation; it’s a distillation of the only two logical possibilities. Cruz’s current performance is just as straight-faced as his 2013 performance, which he now dismisses as fraud. If Cruz told the truth to York and George—if his 2013 amendments were for real—then in the past month, he has lied to Baier, Van Susteren, and many other reporters, not to mention the public.

Second, Cruz got through the entire immigration fight without leaving any solid evidence that he was faking it. That’s remarkable. Last month, FactCheck.org asked Brian Phillips, a Cruz campaign spokesman, whether he could “point to any instances in which Cruz tipped his hand” that the 2013 legalization offer “was not a plan he [Cruz] actually proposed, but was a legislative strategy to make a point.” Phillips said he couldn’t. “We were not trying to let on our legislative strategy,” Phillips explained. But Cruz’s 2013 record is so pristine, so perfectly devoid of nods and winks, that it’s impossible to know what his real game was. And that’s what sets Cruz apart. Lots of politicians lie. Cruz did something more impressive. He talked and talked and still managed to leave himself both options: to deny in the future that his amendments were sincere, or to claim that they were.

Press aides on Cruz’s presidential campaign, and at least one person who worked for him in the Senate, say his offer of legalization without citizenship was never serious. But there are two clues they can’t explain. One is Cruz’s insistence that his amendment adhered to conservative principles. Throughout the 2013 debate, Cruz emphasized that by imposing sufficient “consequences” on lawbreakers, his ban on citizenship made green-card legalization acceptable. He was preparing a rationale that could justify a deal.

The second clue is that Cruz also prepared himself politically. Maybe it was assumed in Cruz’s Senate office that his amendments were fake. Maybe Cruz even said so in private, for what that’s worth. But outside the office, Cruz did something that doesn’t fit that story. He poll-tested legalization in his own state.

On June 19, 2013, Cruz gave a long radio interview to Rush Limbaugh. Today, Cruz claims that this interview turned the tide against the immigration bill. That’s false: A week after the interview, the Senate passed the bill, 68 to 32, and—as Cruz repeatedly argued at the time—the bill, as written, was already doomed in the House. But during the call, Cruz said something curious. “We polled Hispanic voters in Texas,” he told Limbaugh. “We asked, ‘Do you support a pathway to citizenship or work permits that do not allow citizenship?’ And a plurality, 46 percent of Hispanic voters in Texas, supported a work permit without citizenship. And only 35 percent supported a pathway to citizenship.”

Cruz brought up the poll to quote the numbers. But what’s far more interesting is the structure of the poll question, who asked it, and where. This wasn’t a public survey. It was conducted by Cruz’s own pollster, a month after the senator’s election and just before the start of the immigration debate. So the question was written to be useful to Cruz. And the question didn’t pit a path to citizenship against the no-legalization, border-security policy Cruz now claims to have stood for. It pitted a path to citizenship against a different option: “Give them work permits to allow them to work here legally but do not make them eligible for U.S. citizenship.”

Photo by Jonathan Ernst/Reuters

Cruz loved the question. Between June 19 and July 1, 2013, he quoted its results at least three times. The point, he argued, was that Hispanics were on his side. But that explanation left three puzzles. One puzzle was: If Cruz wanted to prove that Hispanics were on his side, why did he ask them about work permits instead of border security? Why would Cruz poll-test a policy of letting undocumented immigrants “work here legally”—and brag about the positive results six months later—if he weren’t seriously considering it?

The second puzzle was: Why Texas? If the survey were designed to influence other lawmakers, the logical sample would have been voters nationwide. Instead, the question was asked only in Cruz’s state. And the third puzzle was the timing. In December 2012, Cruz wasn’t facing an election. He was facing a decision about how to handle immigration.

For me, these two clues—the poll and the “consequences” argument—show that Cruz was serious about legalization. First, he checked out the political benefits and risks in his own state. Then he spent at least two months preparing a public rationale for a deal. But if I’m wrong—if Cruz was never open to work permits or green cards—that’s much worse. It would mean that Cruz polled Hispanics to find out whether, by pretending to offer legalization, he could divide and neutralize them.

We can’t know what Cruz really thought. And we don’t need to know. From the record assessed here, we’ve learned enough about him to decipher his words and predict his behavior. He’s a passionate, indefatigable liar. He speaks with the cadence of a preacher but the craft of a lawyer. When the time for choosing comes, he keeps his options open. Don’t let his vehemence fool you. Watch every word he says.

When you study Cruz this way, through the lens of history, his pretense of clarity dissolves. Last August, he ducked questions about undocumented immigrants, saying “we can have a conversation” about that after the border is secured. In November, he issued an immigration plan that said nothing about a path to citizenship or green cards. When reporters asked Cruz whether he would rule out legalization, he changed the subject.

Cruz has also revived his rationale for a legalization deal. On Nov. 30, at a campaign stop in Iowa, Kasie Hunt of MSNBC asked Cruz to define amnesty. Cruz answered: “I consider amnesty to be forgiving the law-breaking of those who come here illegally, and having no consequences, and in particular a path to citizenship.” These specifications—“no consequences,” “in particular a path to citizenship”—give Cruz space to accept a path to green cards and deny that it’s amnesty. Three times, Hunt asked Cruz the logical follow-up question: “Is a path to legalization amnesty?” Cruz turned and walked away.

In the Las Vegas debate on Dec. 15, Cruz tried to silence the doubters. “I have never supported legalization,” he proclaimed. Rubio, unsatisfied, pressed him: “Do you rule it out?” The time for choosing had come, and Cruz was ready. He turned to Rubio, raised an index finger for emphasis, and vowed: “I have never supported legalization, and I do not intend to support legalization.” I do not intend. There’s nothing more Ted Cruz than that.

See the definitive timeline of what Ted Cruz said and did during the 2013 immigration debate.

Read more of Slate’s coverage of Ted Cruz and the 2016 campaign.