What’s Your Walk Score?

The company that puts a number on walkability.

The first thing to note about Walk Score—the company that tracks the “walkability” of locations around the world—is that its office, in the Laurelhurst section of Seattle, is not exactly a paragon of pedestrianism. Its address, 3503 NE 45th St., garners an 80 on the site—“very walkable.” No question, this is quite respectable, and in some cities would register at the higher stratum of walkability. But in Seattle terms, it’s no Belltown (97) or Capitol Hill (91). It’s just a few notches better than that seeming archetype of postwar suburbia, the Brady Bunch house. “We don’t have quite the Walk Score we would like,” says Josh Herst, the company’s CEO, as we sit in a conference room. “We often talk about moving to Capitol Hill,” adds Matt Lerner, Walk Score’s CTO. Like many startups, Herst notes, Walk Score’s location is based largely on the home address of its founder, Mike Mathieu, for whom the offices are an easy walk.

What does an 80 (and a transit score of 45) mean? For my afternoon visit, it meant I had to take a cab to get there, but that we were able to walk to lunch (to a Thai restaurant whose familiarity with the Walk Score staff hinted at a somewhat limited range of options). It meant that there was a nice multiuse path nearby, but that to get there I had to cross busy 45th Street—I waited so long for a “walk” signal that I jaywalked. It meant that the multiuse path led past a few tricky intersections down to University Village, a self-described “open-air lifestyle shopping center” (useful if you’re shopping for a lifestyle), a place everyone else had seemingly driven to, in order to walk around.

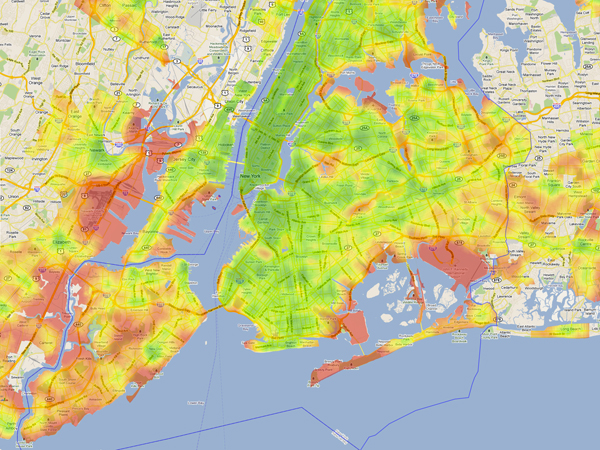

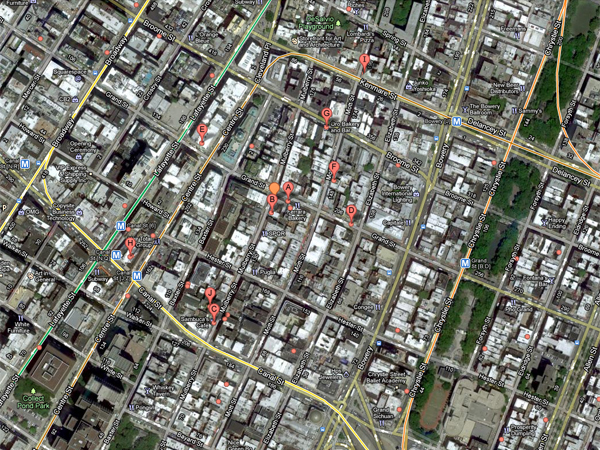

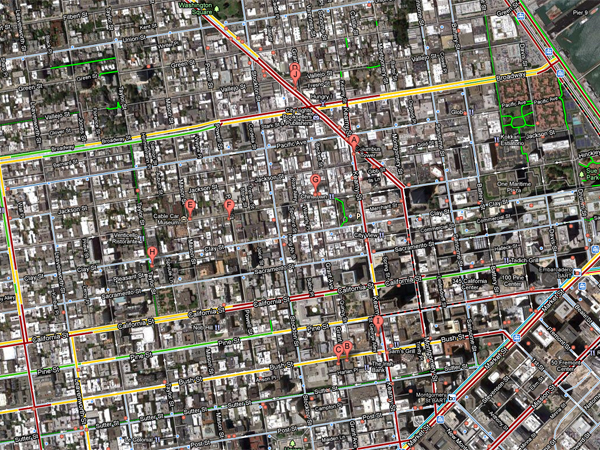

Walk Score is a website that takes a physical address—enter yours here—and computes, using proprietary algorithms and various data streams, a measure of its walkability. More recently it’s started tracking how transit-friendly neighborhoods are too. What drives the score is choice and proximity—the more amenities (restaurants, movie theaters, schools) you have around you, and the closer they are, the higher your Walk Score. I live in a “Walker’s Paradise” neighborhood in Brooklyn, one that earns a perfect 100. (The three-doors-down grocery store is so close I’ve left food cooking while I ran to replenish a missing ingredient.) George W. Bush’s Crawford, Texas ranch rates a 0 (“car dependent”).

Launched in 2007 as part of a series of “civic software” initiatives, Walk Score instantly went viral, and quickly become an institution, particularly in the world of real estate. Walk Score numbers are found on every Zillow listing and on more than 10,000 realtor websites nationwide. Some agencies even allow customers to search for properties by Walk Score. “Even if it’s not the highest Walk Score, people want to know what their neighborhood is going to be like,” says Lerner, as we sit watching a live stream of real-time Walk Score inquiries on a large screen, a flickering array of dots from Los Angeles to Capetown. “They might want the closest grocery store to be two blocks away, but even if it isn’t, they want to know how far it is. What’s the closest place to get coffee? Are there parks and schools nearby?”

Walk Score has also been embraced by the planning community, not simply for its ease of use, but because the single number it provides is easy to communicate. In Phoenix, the city used Walk Score, along with housing and employment data, to help plan proposed light rail stations. Harriet Tregoning, Director of the Office of Planning in Washington, D.C., says Walk Score provides a handy metric that is otherwise often missing from many discussions. “We’re a jurisdiction where 50 percent of our trips are taken by something other than auto.” Retailers, she says, traditionally use car counts to measure the vitality and economic potential of an area. “They’re missing half the traffic,” she says. “I’ve sat across from developers who wanted to do a project and they were able to tell me the car counts at different times of the day, and I said, ‘What about the bus counts?’ They were like, ‘What?’ ” People on foot can be a more elusive quarry—a study of the Fulton Mall in Fresno, Calif., found the amount of pedestrian traffic people perceived was half the actual amount.

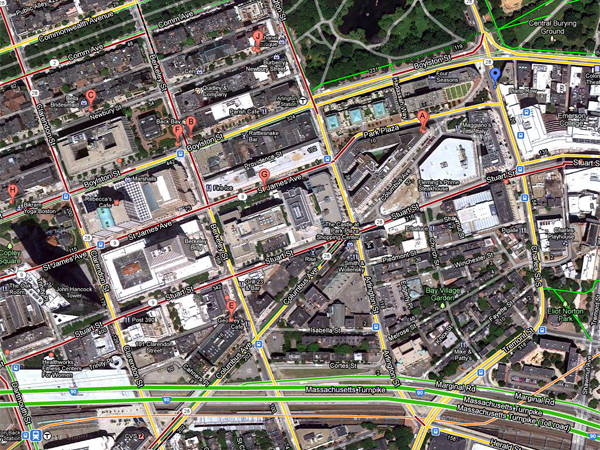

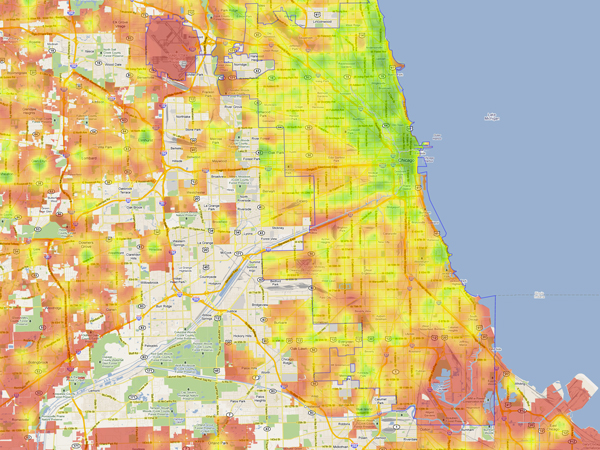

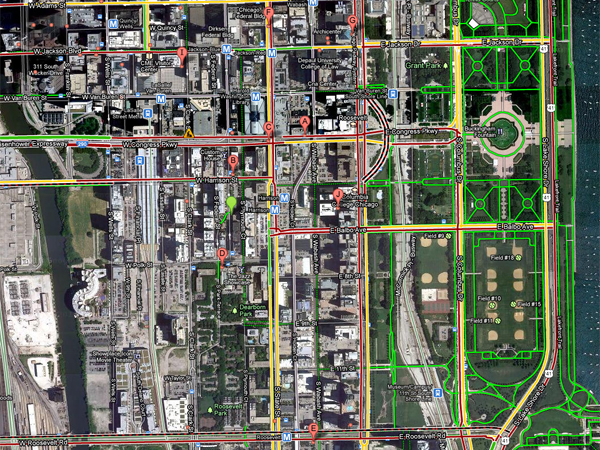

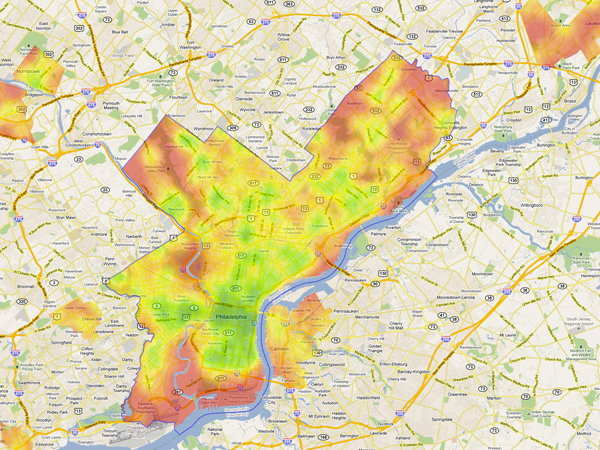

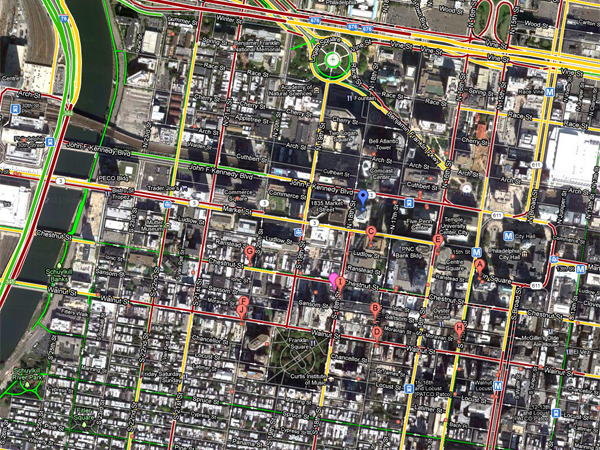

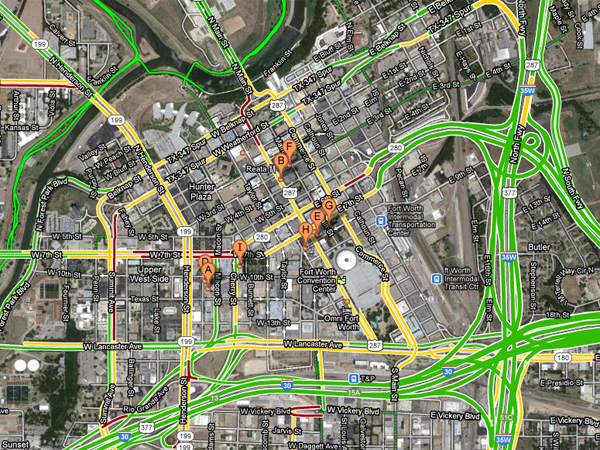

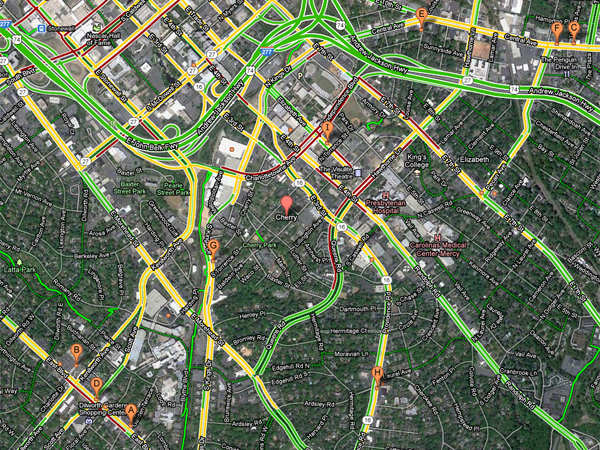

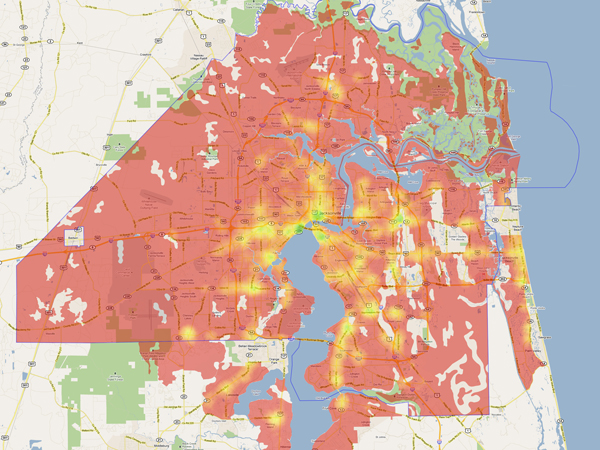

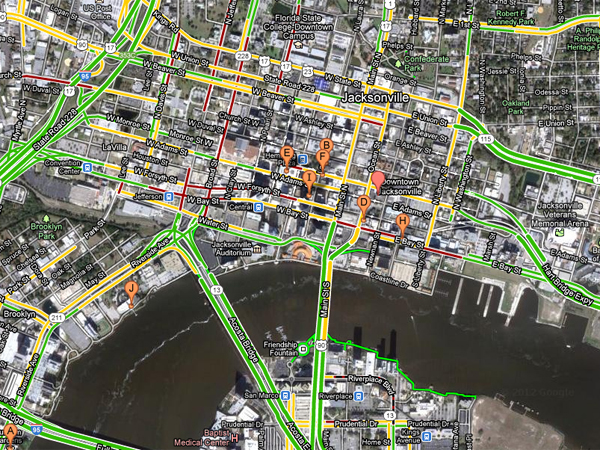

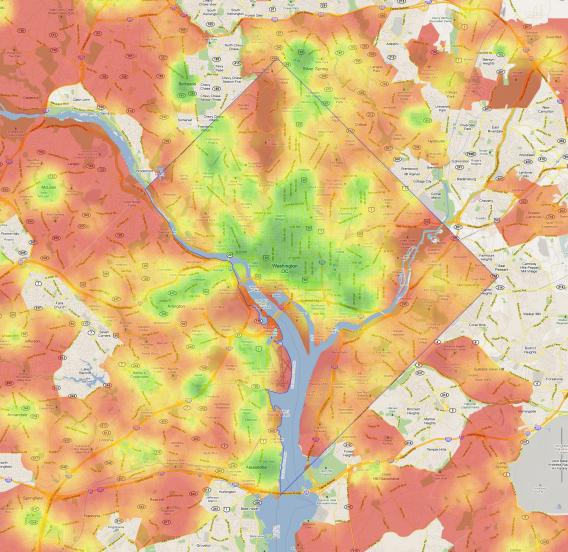

Courtesy Walk Score.

Tregoning envisions Walk Score as a kind of divining rod for developers and officials, a tool that could help them spot opportunities in places that are about to “tip” into walkable urbanism. Tysons Corner, Va., is an archetypal “Edge City,” one of those centerless clusters of office parks and corporate headquarters located a few highway exits away from a major metropolis (in this case, Washington, D.C.). Tysons Corner has, says Tregoning, a “pretty good Walk Score, but it’s anything but walkable.” People in Tysons have been known to drive across the street for lunch. “But it’s not a bad indication that there’s already enough stuff that if you were to overlay a more urban pattern of development, that you would have a lot of the destinations that people would need a daily basis.”

For its part, Walk Score—whose employees are software engineers, not planners—says it brings the immediacy of the software world and the flexibility of open-source mashups to the traditionally staid, black-box world of transportation modeling. “There aren’t a lot of people with software background working on these planning issues promoting walkable and transit,” says Lerner, who like Herst came to Walk Score from Microsoft. For its transit metric, for example, the team created software that collects data from more than 150 transit agencies. When the city of Miami opened up their data on a Friday, the team had a Transit Score on Monday morning. “And these urban planners were like ‘My God, how did you calculate all those scores? Did you work all weekend?’ ” Lerner says. “No, it’s software, it works while you sleep.”

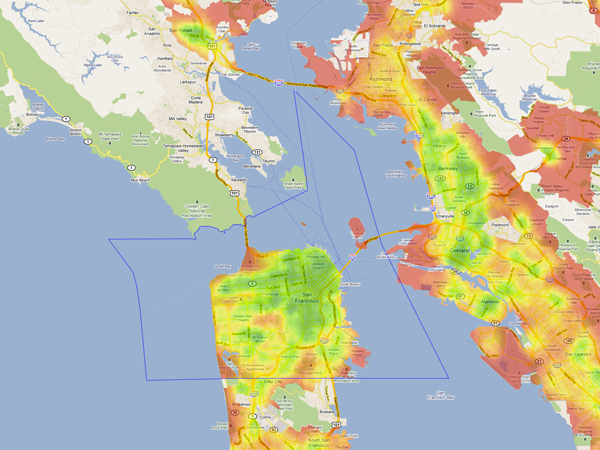

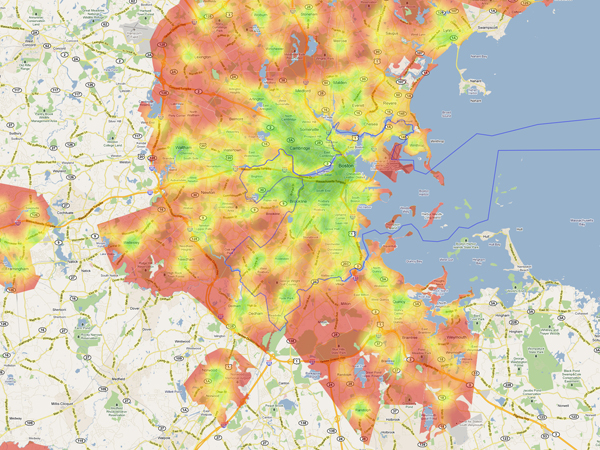

More important than the technology, though, is the idea that Walk Score has quantified walkability, taken an abstract quality—you know it when you see it, sort of—and turned it into something that can be measured against other addresses, other neighborhoods, even other cities (witness the New York versus San Francisco World Series of Walking). Walk Score gets people thinking concretely about walking. “Urban planners have been talking about walkability for a long time, but it’s hard to get people to pay attention,” says Lerner. “But because the scores are so personal, it’s gotten people to pay attention.”

As it parses its carefully selected data parameters, Walk Score has inevitably wandered onto a larger, muddier avenue: By putting a number on walkability, you are essentially defining it. Lerner is comfortable with the way Walk Score has shaped the term’s definition. Before the company launched, “you’d see real estate listings that would say this house is right on the golf course, and it’s super walkable,” says Lerner. “But you actually don’t do most of your daily errands on the golf course. One of the things we did in real estate was really define walkability, as access to amenities, access to transit, living in a pedestrian friendly neighborhood.” The company is also careful to stress the transparency of its methodology. “We’re lining this up with the latest academic walkability research,” says Lerner, “but there are some judgment calls in here so we just want to expose those.”

Of course, Walk Score’s walkability index doesn’t account for all possible behaviors; Consider the low-scoring country dweller who enjoys walking her dog on a rural path. Not to mention that what one person considers a “walkable” trip may seem an epic hike to another. As Bill Bryson once observed, in Notes from a Big Country, about the theoretically walkable Hanover, N.H. (average WalkScore, at least downtown, of 98): “Nearly everyone in town is within a level five-minute walk of the shops, and yet as far as I can tell virtually no one walks.”

But all this leads into a larger question, one that haunts the hazy ground between personal preference and societal planning, which is how Americans actually want to live. Do Americans want sidewalks in front of their houses and actual places to walk to—“Leave the car in the garage!” is a common refrain on real estate sites—or are Americans happy, as transportation analyst Alan Pisarski puts it, to “drive to where they can walk?” Surveys on this question are decidedly mixed. A National Association of Realtors survey found that a majority of people would rather live in a “smart growth” community than a “sprawl community”; the same survey found that a majority, however, were willing to accept a longer drive to shops and restaurants if it meant having a single-family home.

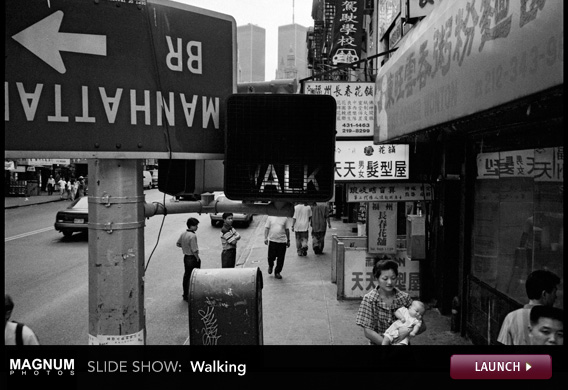

Getty Images/iStockphoto.

What these surveys tend to reveal is that most Americans would like to live in places that don’t really exist. As Barbara McCann, director of the National Complete Streets Coalition, says, “people want a big house on a big lot, where there are stores they can walk to.” The truth is there are relatively few places in America that today would pass what architect Hal Box has dubbed the “Popsicle Rule”—“a child must be able to walk safely from home to buy a Popsicle within five minutes.” (And given the current concerns about childhood obesity, make that an organic-fruit-no-corn-syrup-added-Popsicle). Lerner tells me that the largest 2,500 cities in the United States together have an average score of 43 (“car dependent”). As urban scholar Christopher Leinberger notes, “In most metropolitan areas, only 5 to 10 percent of the housing stock is located in walkable urban places.” Some of those buyers who might like to buy in a walkable area, he adds, simply cannot afford to—at least in the way they would desire. “Some of the naysayers say people want to live in this sprawling way,” says McCann. “But then why is it that houses in the urban areas are so expensive? The market’s saying it’s valued—it’s so expensive most people can’t afford it.”

The nexus of walkability and real estate value is one place where researchers have turned to Walk Score. One study, conducted by economist Joe Cortright for CEOS for Cities, found, “after controlling for all of these other factors that are known to influence housing value,” that one point on Walk Score was worth anywhere from $500 to $3000 for a house’s value. Another study, in the Journal of Sustainable Real Estate, found that higher Walk Scores “were negatively related to mortgage default,” (and, conversely, each additional household vehicle owned increased the probability of default). Other studies are using Walk Score to examine the link between where people live and how healthy they are.

Walk Score’s methodology is not always accepted uncritically. Virtually since its release, people have been finding flaws, which the company itself is happy to admit. Lerner jokes that in real estate, its methodology is rarely questioned: “Oh, an 84? Must be an 84!” Planners, however, start invoking a litany of criteria like lot size or legibility. Early on, the “crow flies” distance and routing calculations generated improbable results, suggesting that locals might walk across bodies of water, or frequent seemingly walking-distance shopping malls that were on the other side of interstate highways. The application’s picture of walkability has also been limited by what data it has access to—it’s tough to tell, for example, whether streets are well-lit. Still, “there’s so much that’s possible,” says Lerner. “Cities even have databases of where their street trees are and how old they are.”

Yoshikazu Tsuno/AFP/Getty Images.

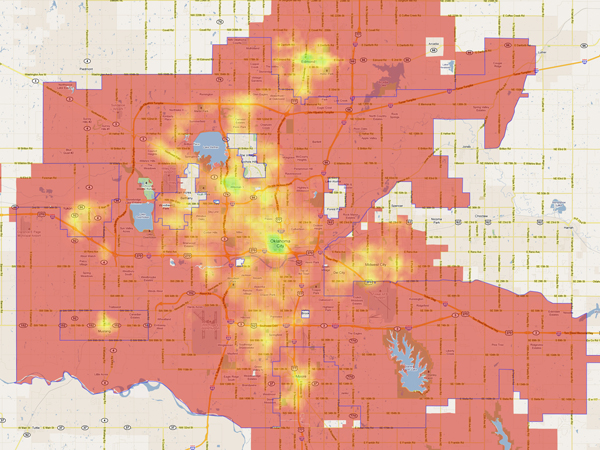

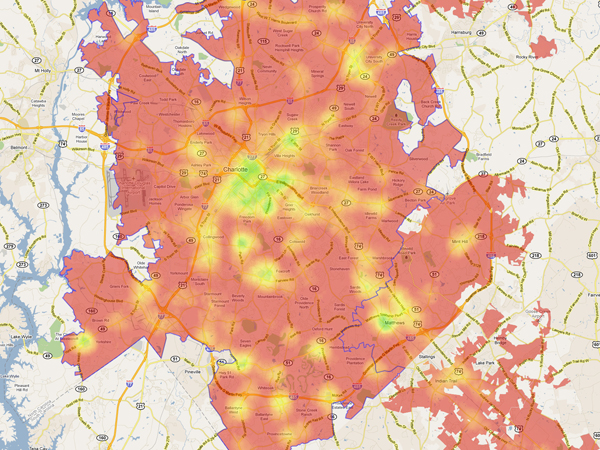

Ideally, Walk Score would track infrastructural and environmental issues: Does a street have good (or any) sidewalks? How long do you have to wait for the light? What’s the traffic volume? How many pedestrians have been struck in the crosswalk by turning cars? What’s the street level temperature? The company would also do well to recognize that proximity does not always equal walkability. Scott Bricker, the director of America Walks, says, “If you do a Walk Score search on Beaverton Transit Center, in suburban Portland, it has a Walk Score of 96, off the charts,” he says. “If you look at a Google Map, you see you can’t walk anywhere. It’s all strip mall stuff, five lane streets.” Indeed, Walk Score (guided by an advisory board) has been trying to refine its metric, and an ongoing beta service, called “Street Smart Walk Score,” factors in actual walking routes, including an amoeba-like “zone” of everything that can be walked to in 15 minutes. It also features variables like shorter block lengths and frequency of intersections—two factors urbanists associate with more walkable places. But here, too, data is lacking. “There isn’t a good national dataset of crosswalks,” Hersh says.

In the end, there may simply be factors that resist Walk Score’s methodology. There are numerous ways we judge how good a place is for walking, but many of these tilt into the decidedly subjective. Copenhagen’s Strøget, for example, is a street that urbanists often cite as a car-free pedestrian Valhalla, which it is; and yet, in a Berra-esque turn, I find it too crowded, so I always avoid it. “We’re looking at how to start including human commentary in our ratings,” says Lerner. “It’s a tricky issue. You have to be wary of people gaming the system; also, aesthetics are important to people.” (Planner Jarret Walker wonders: “Is someone working on a computer algorithm that will study every Street View photo in the country and assign a universally-respected "design score"?) Walk Score has also contemplated using anonymized cell photo data to track how crowded streets might be. Here it’s easy to imagine the possibilities for various mashups: Merge Walk Score with, say, MIT’s Real Time Rome project to see how much walkable neighborhoods and streets correlate to actual walking (something that researchers have already examined, at least in the analog sense). The company is also currently investigating a “Bike Score,” which adds another layer of complexity. “Biking just takes you over a much broader geometry, so it’s less about the specific address and more about the area that you can bike in,” says Lerner. “We have some ideas at how to look at the bikeable area from an address.”

Whatever the methodological hurdles, and however incomplete any one single “score” can ever be, Walk Score has already been successful in its core goal, as described by Lerner: “How do we make walkability and transit and commuting part of how people decide where to live?” Realtors have always touted “location, location, location,” but nothing puts the point on it better than a number. “Some twenty million people a month are seeing a metric of transit service on a real estate listing,” says Herst. Until now, “there’s never been anything on a real estate site that tells you whether that house is well served by transit. Having that many people see it, is, from a mission perspective, very exciting.”

More from this series: The troubling fact that Americans walk less than almost anybody; what scientists learn when they study pedestrians; how America can get people walking again.