Why Boston Desperately Needs More Hispanic Teachers

Its population of Hispanic students is booming, but fixing that imbalance is only the first step toward a truly equitable school district.

Antonio Arvelo

BOSTON—Antonio Arvelo showed up for freshman year at Georgetown University in 1995 with two garbage bags full of clothes, barely any money in his pocket, and a massive inferiority complex. Unlike the vast majority of his classmates, he had grown up poor, the son of immigrant parents from Ecuador and the Dominican Republic. The first person in his family to attend college, he arrived alone in Washington, D.C., with a major goal. “I thought I needed to follow the path to make the most money and buy my mother a house,” he says. “Honestly, I was just tired of being poor.”

Teaching, obviously, was not high on the list of prospective career paths. It wasn’t until his late 20s that Arvelo finally felt secure enough to pursue what turned out to be his true professional calling. Nearly a decade later, as a male Latino teacher in Boston, he is a member of a rare and highly desired demographic. In Boston, Hispanics make up just 10 percent of the public-school teaching corps but a plurality of the student body, at more than 40 percent. In the United States, the percentage of Hispanic students swelled from 18 percent in 2002 to 24 percent in 2012; within 20 years, more than a third of America’s public schoolchildren will likely be Hispanic.

Yet Hispanics remain one of the most underrepresented groups among teachers’ ranks, particularly outside of western states like Texas and New Mexico. Arvelo’s story speaks to the challenges of recruiting and retaining more Hispanic teachers in regions like New England, where the population has skyrocketed—but there’s no large base of Spanish-speaking teachers.

His story also speaks to the broader question of whether Hispanic students need mostly Hispanic teachers. Is it enough, for instance, for low-income students of color to have black or brown teachers of any ethnicity? Or is it important that some teachers come from the same racial and ethnic group, culture, socioeconomic class, and gender as their students? In other words, to what extent can members of one oppressed minority group relate to the experiences of another? When it comes to teacher-student demographics, should we be striving for a perfect match?

No individual teacher’s experience provides tidy answers, of course. Arvelo, for instance, says he feels drawn to teaching “any and all youth growing up in poverty,” regardless of their skin color or cultural heritage. But today he teaches primarily Latino students, some of whom “place a lot of value in that [Latino] part of their identity—more than I did.”

Boston’s example teaches us that the goal of achieving a perfect match between student and teacher populations may be idealistic and next-to-impossible, but it’s not fruitless. Our notion of teacher diversity has to remain as fluid and flexible as the students themselves.

* * *

Growing up in the 1980s in New York City’s Hell’s Kitchen neighborhood before it gentrified, Arvelo had only two Latino teachers in elementary school. “It was normal,” he says. “I didn’t think then about what it meant to have white people teaching brown people.”

As Arvelo grew older, some of those white teachers viewed him as a troublemaker at least partly, he believes, because he was a poor, male, and Latino. The stereotype became something of a self-fulfilling prophecy. In seventh grade, he was expelled for being an onlooker during a fight, and for a year-and-a-half attended an alternative school for troubled students.

At home, Arvelo lacked a strong male role model: His stepfather abused cocaine—and Arvelo’s mother. One afternoon when he was 15, Arvelo returned home to find the apartment full of police and medical personnel: In a rage, Arvelo’s stepfather had stabbed his mother and tried to break her fingers.

The family fled to Boston. There, Arvelo lived with his mother, brother, and sister in a shelter for abused women before moving into transitional housing. He started his junior year at West Roxbury High (known as Westie). In the early 1990s, Westie enrolled a mixture of African American, Latino, Haitian, and white students, according to Arvelo. All of his teachers were white except the gym instructor and guidance counselor.

During his first month at Westie, Arvelo visited the guidance counselor’s office hoping to talk about joining the military after high school. He didn’t see himself in college. Arvelo says she shooed him away and closed the door to her office; he apparently wasn’t worth her time.

The counselor became much more receptive a few months later when Arvelo got back his PSAT scores—the highest of any student in the school. Suddenly, he didn’t have to seek his school’s attention. He was called on to meet Boston’s mayor and other officials when they visited West Roxbury. “It wasn’t until my PSAT score that the school cared about me,” he says. “They took advantage of me, and I took advantage of them. It shouldn’t be a give-and-take from a school. It should just be a give.” Today, he tries not to make the same mistake with his own students by reaching out to the most challenging ones while also encouraging them to become the kind of student even the most neglectful school would care about.

Antonio Arvelo

Arvelo got into Dartmouth, Bates College, Boston University, and Georgetown, ultimately choosing the latter—in part because it held a special recruitment weekend for prospective minority students. At Georgetown, he met several wealthy black and brown people for the first time, and found their academic strength intimidating. But, over time, he came to understand that for some their privilege had as much to do with money, socialization, and confidence as with smarts and hard work.

At some level, Arvelo says he always wanted to be a teacher, but he lacked role models in the profession and the economic confidence to take a lower-paying job. After leaving Georgetown, he entered the corporate world. His last stint was as a sales representative for the publishing giant Pearson. Although he had lobbied hard for the position, the job left him cold: “I just felt hollow selling books to universities.”

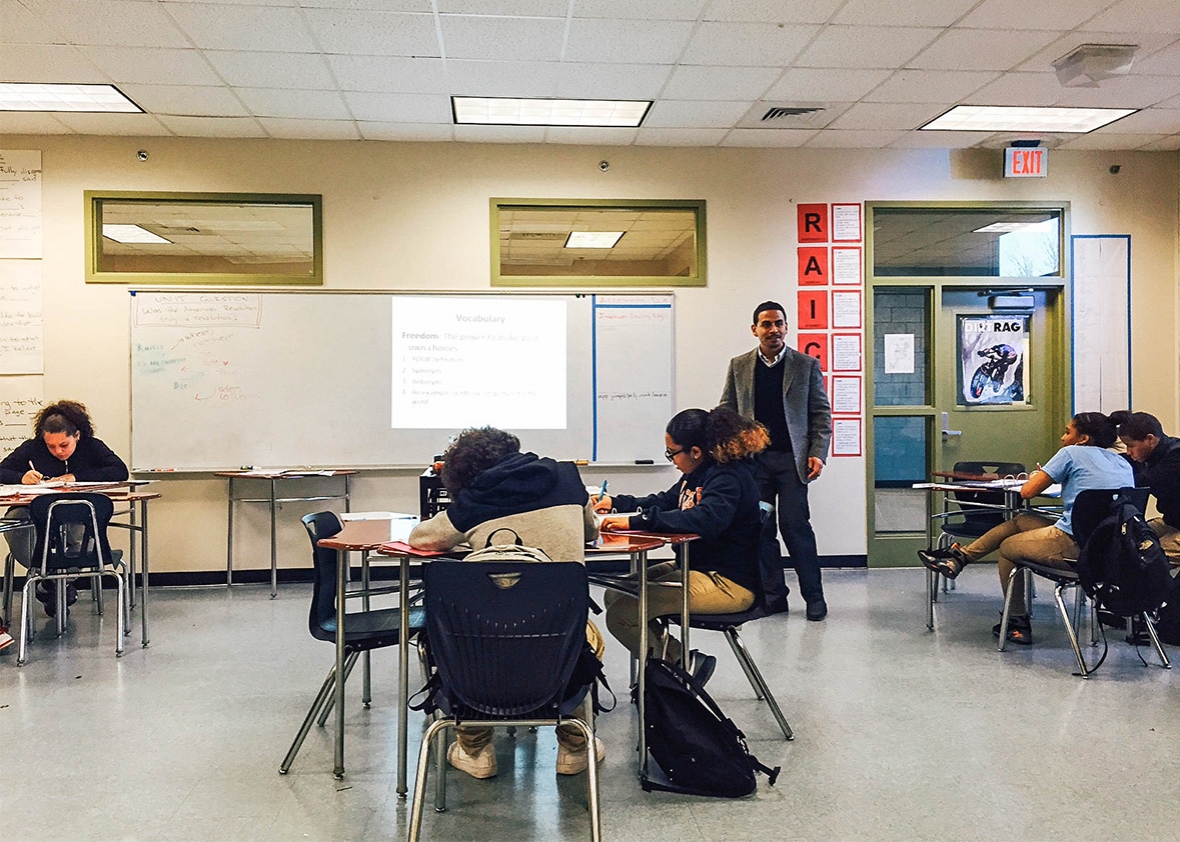

Arvelo finally recognized that he would be happier in a less lucrative but more personally fulfilling career. He decided in his late 20s to train to become a teacher through the Boston Teacher Residency, which works with many midcareer changers. Arvelo taught for five years at two other Boston high schools before starting last fall at the Margarita Muñiz Academy, a high school where classes are taught in both English and Spanish.

* * *

Of the more than 15,500 people studying or training to become teachers in Massachusetts in 2013, about 4 percent—or 580—were Hispanic. Statewide, 11 percent of the population is Hispanic, compared to nearly 20 percent of Boston residents and more than 40 percent of Boston public school students.

In Boston, schools with predominantly white students tend to have predominantly white teachers. The same isn't true of schools with predominantly black or Hispanic students.

Source: Massachusetts Department of Elementary and Secondary Education, School and District Profiles. Data is from 2014-2015.

Hispanics are far less likely than non-Hispanic whites (or black Americans, although the disparity is far smaller) to train to become teachers for myriad reasons. They’re more likely than whites to grow up in poverty and struggle in school. And they are less likely to pursue higher education of any kind. Those who do excel in school and rise out of poverty, like Arvelo, often don’t view teaching as a viable career.

In some areas, including parts of Alabama, Tennessee, and North Carolina, the Hispanic population is so new that the community has yet to put down roots and develop a significant professional presence outside of the working-class industries that drew them there. Even in communities where Latinos are more established, children often have few Latino teachers to model themselves after. Efrain Toledano, principal of Boston’s Maurice J. Tobin K–8 School, had just two Latino teachers when he was a student in Boston. “It completely changed the trajectory of my life,” he says. “It made me feel that it’s cool to be a thinker … standing in front of a classroom.”

Jordan Weymer, principal of Boston’s McKay School, says most Latino teacher applicants get snapped up immediately. He makes a point of interviewing every “diverse candidate” that applies to teach at McKay.

One way to attract more candidates is to look outside of Massachusetts. Beatriz McConnie-Zapater, a longtime educator and former school leader in Boston, says the district used to be more proactive in seeking Latino teachers from around the world. But the district claims to have had little luck with out-of-state recruitment efforts in places like Puerto Rico or New Mexico. Such efforts often yielded “zero new hires,” says Emily Qazilbash, the Boston assistant superintendent who oversees staffing and hiring. Of last year’s 1,000 new teacher hires, only 27 listed an address outside of Massachusetts, she says.

Instead, the district is focusing on locally cultivating a diverse workforce. Last year, for instance, it started a program that provides mentoring, networking, and other opportunities for high school students interested in education. Almost all of the participants are students of color.

Boston officials hope this high school–to-teacher program will capture students like Arvelo at a much earlier age. Indeed, showing young Latinos the rewards of teaching, and providing them with Latino role models whenever possible, may be one of the most effective ways to attract them to education.

Natan Santos, a 17-year-old high school junior who participates in the new program, says he hadn’t thought about teaching before a guidance counselor recommended him for the program. He had no Latino teachers at his elementary and middle schools—a deficit he now hopes to help correct for future generations.

“If you come from an immigrant family like me, you are supposed to go to college, graduate, and get a high-paying job,” he says. “A big problem is how teaching is looked at. It’s not looked at as a glamorous job.”

If he ultimately goes into teaching, Santos wants to serve as a mentor and inspiration for Latino students, particularly teenage males—someone who “understands where the students are coming from” and cares about them “outside of the classroom.” More Latinos would consider teaching, Santos says, if the district “highlighted the impact someone could have on their community.”

* * *

The Latino experience in Boston public schools suggests that our notion of what constitutes a diverse workforce is outdated in many parts of America. It’s derived from desegregation-era policies that, while well-intended, had the stifling effect of defining diversity in terms of black and white. And it’s derived from centuries of racist thought that placed all Americans in one of two categories: “white” and privileged—and everybody else.

Ironically, many Hispanics don’t really count as prized diversity hires for the Boston public schools—at least not when it comes to the legal definition in the courts. In 1985, U.S. District Judge Arthur Garrity mandated that 25 percent of the city’s public school teachers be “black.” He also ordered that at least 10 percent come from other minority groups, but said nothing specific about Hispanics (who now exceed African Americans in the city’s schools).

The order followed a school desegregation plan that called for cross-city busing of students and led to several violent incidents throughout the city. In one case, a white teenager attacked a black civil rights attorney with an American flag in front of Boston City Hall. Another time, a black teenager nearly stabbed a white student to death at South Boston High School. White Bostonians mobbed the building in retaliation, trapping several black students inside.

Most educators agree that Garrity’s order was necessary at the time. But more than 30 years later, the mandate’s become somewhat outdated, particularly given the growth in the city’s Hispanic population.

“I would describe our way of thinking as a city as pretty black and white,” says Jesse Solomon, executive director of the Boston Teacher Residency. “There are black people, and then there are white people.”

But at the Muñiz Academy, the high school where Arvelo currently teaches, that reductive dichotomy does little to capture the diversity of the school staff. Twenty-two of the school’s 35 staff members identify as Latino, says Dania Vázquez, the school’s headmaster. But only five of those Latinos identify as black. According to the state website, which just includes teachers, the school had 16 Hispanic teachers, 8.6 white ones, and zero African Americans during the 2014–15 school year. (Hispanic, unlike black or African American, refers to an ethnic and linguistic heritage, not a racial group. When possible, Arvelo checks both the “white” and “black” boxes on forms. But overall, he says he identifies more with the African part of his ancestry than the “white” part.)

“My school shows up as not meeting the court order because we don’t have 25 percent black,” says Vázquez. “We don’t look like we’re meeting our fair share, but we’re more than meeting our fair share.”

In Boston and elsewhere, even Latino students’ backgrounds and needs vary tremendously. Vázquez points out that a recent refugee from El Salvador sees the world very differently from a second-generation immigrant whose parents came from Puerto Rico.

“Within the Latino community there is racism,” she says. “It’s about whether you are black Latino or white Latino. It’s about class. It’s about kinky hair. In my own family, we have conversations about who is light-skinned and who is dark-skinned.”

“While we can say, ‘Latino,’ we are as diverse a group as you can imagine,” she adds. Indeed, one reason Boston needs more Latino teachers is to attain greater diversity of background, culture, and skin color within that broad group.

When I interviewed four immigrant students from the Sociedad Latina, an organization that works with Latino youth and families throughout the city, it struck me how different their needs and desires were when it came to their teachers. One spoke of economic isolation—and the feeling that he had no one to talk to while his family bounced from shelter to shelter, rifling through the trash for food and clothing. A second complained of masses of white teachers teaching mostly black and brown students—likening the educational challenges of black Americans to those of Latinos and Asians. A third spoke of linguistic and cultural alienation.

“I was always reminded that if I didn’t know English, I shouldn’t be there,” says Wilmer Quinones, who moved from the Dominican Republic to Boston as a 10-year-old in 2004, and enrolled in the city’s schools. “It felt like there was a distrust of Latino students because they couldn’t understand what we were saying.”

Quinones, now in his early 20s, serves as youth engagement coordinator at the Sociedad Latina. He and the students he works with agree that having more teachers who look and talk like them isn’t just a matter of being inclusive. It’s a matter of civil rights.

* * *

Antonio Arvelo

Having had a door closed in his face the first time he went to talk to a high school counselor, Arvelo tries to open doors for his own students, literally and figuratively.

On a sunny day last fall, he took a freshman humanities class at Margarita Muñiz Academy on their first college tour at nearby Northeastern University. The tour guide—a tall, blonde, white student named Chris—arrived on a skateboard. He explained that he grew up in Norwich, Vermont. Seeing blank stares from the Muñiz students, Chris clarified that Norwich is very close to Dartmouth College.

The blank stares continued. Throughout the tour, Arvelo quietly filled in necessary context for the students whenever Chris left them grasping.

After visiting a dorm room, Arvelo remarked, “I remember that experience.”

“What college did you go to?” a student asked.

“Georgetown.”

“That costs a lot of money.”

“I didn’t pay a lot. My family didn’t have a lot of money, so they gave me a scholarship.”

The student nodded.

Probably no school district in the U.S. will ever attain a perfect match when it comes to student-teacher demographics. But Arvelo’s experience suggests that we should strive to cultivate teachers at much younger ages from the most alienated and underserved communities in our schools—including poor Hispanic students in Boston who too rarely contemplate a career in the classroom.

We must also avoid treating different groups—whether students of color or students growing up in poverty—as a monolith, with the same needs and desires when it comes to their educations. And to do that we have to see, and understand, differences that go far beyond black and white.

It’s past time for school districts across the country to live up to the spirit—if not the letter—of Judge Garrity’s historic ruling: Recognizing that hiring more teachers who understand students’ cultures should be viewed as a matter of equal education access, not a fortunate happenstance for a privileged few.

Tomorrow’s Test is a weeklong series looking at the challenges, tensions, and opportunities as the United States shifts to a majority-minority student population in its public schools—a milestone the country as a whole will reach within the next generation. It is a collaboration with the Teacher Project at Columbia Journalism School, a nonprofit education reporting fellowship.

Read more from Tomorrow’s Test.