Read Playboy … for the Interviews

Six great conversations from the magazine’s archives.

AFP/AFP/Getty Images.

Every weekend, Longform shares a collection of great stories from its archive with Slate. For daily picks of new and classic nonfiction, check out Longform or follow @longform on Twitter. Have an iPad? Download Longform’s app to read the latest picks, plus features from dozens of other magazines, including Slate.

Hey, a chance to actually read Playboy for the articles! Or, rather, the interviews. Playboy published its first interview 50 years ago, and to celebrate the anniversary the magazine has put out a series of ebook compilations of its favorite conversations. The series, 50 Years of Playboy Interviews, is available on Amazon. Below, reprinted in full and for free, are six we particularly enjoyed.

Frank Sinatra

Interviewed by Joe Hyams • February 1963

Playboy: Many explanations have been offered for your unique ability—apart from the subtleties of style and vocal equipment—to communicate the mood of a song to an audience. How would you define it?

Sinatra: I think it’s because I get an audience involved, personally involved in a song—because I’m involved myself. It’s not something I do deliberately: I can’t help myself. If the song is a lament at the loss of love, I get an ache in my gut. I feel the loss myself and I cry out the loneliness, the hurt and the pain that I feel.

Playboy: Doesn’t any good vocalist “feel” a song? Is there such a difference.…

Sinatra: I don’t know what other singers feel when they articulate lyrics, but being an 18-karat manic-depressive and having lived a life of violent emotional contradictions, I have an overacute capacity for sadness as well as elation. I know what the cat who wrote the song is trying to say. I’ve been there—and back. I guess the audience feels it along with me. They can’t help it. Sentimentality, after all, is an emotion common to all humanity.

Playboy: Of the thousands of words which have been written about you on this subject, do you recall any which have accurately described this ability?

Sinatra: Most of what has been written about me is one big blur, but I do remember being described in one simple word that I agree with. It was in a piece that tore me apart for my personal behavior, but the writer said that when the music began and I started to sing, I was “honest.” That says it as I feel it. Whatever else has been said about me personally is unimportant. When I sing, I believe. I’m honest. If you want to get an audience with you, there’s only one way. You have to reach out to them with total honesty and humility. This isn’t a grandstand play on my part; I’ve discovered—and you can see it in other entertainers—when they don’t reach out to the audience, nothing happens. You can be the most artistically perfect performer in the world, but an audience is like a broad—if you’re indifferent, endsville. That goes for any kind of human contact: a politician on television, an actor in the movies, or a guy and a gal. That’s as true in life as it is in art.

Steve Jobs

Interviewed by David Sheff • February 1985

Playboy: You’ve said that the business market is crucial for you to conquer with Macintosh. Can you beat IBM at work?

Jobs: Yes. The business market has several sectors. Rather than just thinking of the Fortune 500, which is where IBM is strongest, I like to think of the Fortune 5,000,000 or 14,000,000. There are 14,000,000 small businesses in this country. I think that the vast group of people who need to be computerized includes that large number of medium and small businesses. We’re going to try to be able to bring some meaningful solutions to them in 1985.

Playboy: How?

Jobs: Our approach is to think of them not as businesses but as collections of people. We want to qualitatively change the way people work. We don’t just want to help them do word processing faster or add numbers faster. We want to change the way they can communicate with one another. We’re seeing five-page memos get compressed to one-page memos because we can use a picture to express the key concept. We’re seeing less paper flying around and more quality of communication. And it’s more fun. There’s always been this myth that really neat, fun people at home all of a sudden have to become very dull and boring when they come to work. It’s simply not true. If we can inject that liberal-arts spirit into the very serious realm of business, I think it will be a worthwhile contribution. We can’t even conceive of how far it will go.”

George Carlin

Interviewed by Sam Merrill • January 1982

Playboy: Is that something you did on one of your coke runs after all the nuts and bolts were sorted?

Carlin: There are two types of people: One strives to control his environment, the other strives not to let his environment control him. I like to control my environment, because I feel if I have my physical space in order, then I’m free to dream. So there is some compulsion involved. But the dividend I get is the freedom to be totally disorderly in my dreamworld.

Playboy: What about all these hundreds of signs you have on the walls? Although they’re all very interesting and funny, they’re also obviously stolen.

Carlin: I guess that makes me part vandal, part museum curator.

Playboy: Do you enjoy stealing?

Carlin: I think it keeps the child alive in me. There’s a thrill when you steal something in plain view of other people. When you drop a newspaper over a sign and walk away with it, or take something off a wall and the sound of the glue ripping makes people turn around. Your heart is racing, it’s a rush.

Playboy: The one in the bathroom is marvelous: “The Maclaine Hotel Commemorative Nixon Visit, 1968.” And Nixon signed it at the bottom.

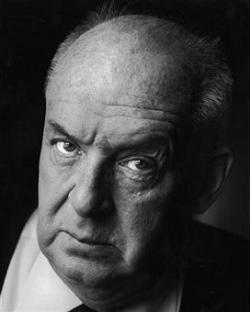

Vladimir Nabokov

Interviewed by Alvin Toffler • January 1964

Playboy: While we’re on the subject of self-appraisal, what do you regard as your principal failing as a writer—apart from forgettability?

Nabokov: Lack of spontaneity; the nuisance of parallel thoughts, second thoughts, third thoughts; inability to express myself properly in any language unless I compose every damned sentence in my bath, in my mind, at my desk.

Photo by Horst Tappe.

Playboy: You’re doing rather well at the moment, if we may say so.

Nabokov: It’s an illusion.

Playboy: Your reply might be taken as confirmation of critical comments that you are “an incorrigible leg puller,” “a mystificator” and “a literary agent provocateur.” How do you view yourself?

Nabokov: I think my favorite fact about myself is that I have never been dismayed by a critic’s bilge or bile, and have never once in my life asked or thanked a reviewer for a review. My second favorite fact—or shall I stop at one?

Playboy: No, please go on.

Nabokov: The fact that since my youth—I was 19 when I left Russia—my political outlook has remained as bleak and changeless as an old gray rock. It is classical to the point of triteness. Freedom of speech, freedom of thought, freedom of art. The social or economic structure of the ideal state is of little concern to me. My desires are modest. Portraits of the head of the government should not exceed a postage stamp in size. No torture and no executions. No music, except coming through earphones, or played in theaters.

Gene Siskel and Roger Ebert

Interviewed by David Sheff • October 1995

Siskel: As a critic, I try very hard to say exactly what I think. And in a medium in which we are well-known for the binary thumbs up and thumbs down, I try to be able to give the mixed review. But most pictures fall into that middle ground, so I wrestle over which way my thumb is going to turn. It’s not flip.

Ebert: I actually respect Gene—he’s an extremely good, highly competent and skilled journalist. He’s always on the phone and he usually knows things, like, Who’s in town? When can I get to them? How can I do this without his finding out?

Playboy: You praise his reporting, but the question was about Gene as a critic.

Ebert: To my way of thinking, he’s lacking in enthusiasm. He’s just a little bit too standoffish and cold about the movies. He thinks the movie is going to be shit, and if it is, that just confirms his suspicions. I go to the movies anticipating a good time. Gene goes fearing a bad time. My glass is half full, his glass is half empty. These are two fundamentally different personalities at work, and they reflect themselves in our reviewing.

Siskel: I’ve heard Roger say that before and I don’t believe it’s true. I want movies to be good. I’d have to be a masochist to want them to be bad. But if you were to stop me any day and say, “Gene, do you expect to see a good movie or a bad movie today?” I would tell you I’m expecting to see a bad movie. The reason is that most of the movies I see are bad. I’m being practical in telling you that most of the things that people create aren’t all that interesting, and that’s too bad. What keeps me going is that I have a strong desire to see something great. And when I see it, it lasts for a long time.

Ebert: One of the big differences between Gene and me is in the area of competence. Gene prides himself on being incompetent when it comes to anything technical. He actually becomes retrograde. No human being alive has had more trouble with computers than Gene Siskel has.

Snoop Dogg

Interviewed by David Sheff • October 1995

Playboy: So it’s not about only money?

Dogg: Yeah. It’s like having nothing, no hope, nothing. Look at the way they’re letting gangs and shit go on so there is black-on-black crime and murder. What does it show? It shows they don’t give a fuck. I could show you a picture of my Pop Warner football team. There were 28 homies on that team. Twelve are dead. Seven are in the penitentiary. Three are smoked out. If they ain’t dead or in jail or smoked out, they do the gang thing, sell dope. I can’t look at that picture and say, “Well, hey, he went to college. He got a degree. Hey, that’s little Johnnie Cochran.” I can’t speak from that shit, because I don’t know nobody in that. I’m 24. To see 24 is an accomplishment. I’ve seen a lot of my homies burned.

Playboy: You finished high school. Were you tempted to drop out?

Dogg: Hell yeah. I was making money. By the time I got to 12th grade I was making $1000 a week.

Playboy: Then why did you remain in school?

Dogg: It was fun. I was popular as fuck in school. I was fun to be around. Motherfuckers loved me for my rap, they loved me because I made them laugh. Whenever I was in class, I fucked with the teachers, I fucked with the students. I wasn’t yearbook class clown or funniest person, but the motherfuckers knew me. I rapped at lunchtime and quick as fuck the crowd got bigger. The principal tried to suspend me, telling me I started a riot at the school. I said, I’m just rapping. These motherfuckers want to hear what I’m saying. So the principal said OK, you can do it.

Have a favorite piece that we missed? Leave the link in the comments or tweet it to @longform. For more great writing, check out Longform’s complete archive.