In Holland, Santa Doesn’t Have Elves. He Has Slaves.

The racist Christmastime tradition Dutch people have begun fighting about.

Photograph by Toussaint Kluiters/AFP/Getty Images.

As a newcomer to the Netherlands, I do many things wrong. I forget to bring gifts to dinner parties, I thank people too profusely, and often speak too personally with people I've just met. But no slip-up has provoked a more troubled response than when I've brought up my concerns about Santa Claus.

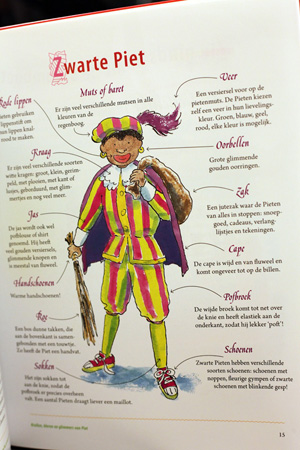

Here’s what concerns me: In Holland, Santa, or “Sinterklaas,” as he’s known to the Dutch, doesn't have reindeer; he has a little helper named Zwarte Piet, literally Black Pete, who charms children with pepernoten cookies and a kooky demeanor while horrifying foreign visitors with his resemblance to Little Black Sambo. Each year, on Dec. 5, the morning before the feast of St. Nicholas, children all over the country wake up excited for gifts and candy while thousands of adults go to their mirrors to apply brown paint and red lips. In their Zwarte Piet costumes, they fill central Amsterdam and small village streets, ushering in the arrival of Sinterklaas who, in the Dutch tradition, rides a flying white horse.

Trying to tell a Dutch person why this image disturbs you will often result in anger and frustration. Otherwise mature and liberal-minded adults may recoil from the topic and offer a rote list of reasons why Zwarte Piet should not offend anybody. “He is not even a black man,” many will tell you. “He is just black because he came down the chimney.” Then, you may reply, why aren’t his clothes dirty?

As the history of Zwarte Piet makes clear, that chimney-soot explanation doesn’t wash. Zwarte Piet—or his immediate ancestor, anyway—was introduced in 1845 in the story “Saint Nicholas and his Servant,” written by an Amsterdam schoolteacher named Jan Schenkman. In the story, Sinterklaas comes from Spain by steamship bringing with him a black helper of African origin. The book was wildly popular and with it began the inclusion of Santa’s helper in Dutch Christmas festivities. (It wasn’t until later in the century that he was given the name Piet.)

At the time, the Dutch empire spread across three continents and included the colonies of Suriname and Indonesia. The Dutch were deeply involved in the slave trade, both transporting African slaves to be sold and using slave labor to work coffee and sugar plantations in their colonies. Minstrel shows were a popular form of entertainment.

Nowadays, Sinterklaas comes to Holland by steamship in mid-November of each year. He is played by a nationally beloved actor, and his arrival is a live televised event that kicks off the holiday season much like the Macy’s Day Parade in the United States. The city bestowed the honor of hosting Sinterklaas’ arrival changes each year.

This year, on Nov. 12, as Sinterklaas prepared to make his grand entrance in Dordrecht, Quinsy Gario was being held on the ground and pepper sprayed by police officers. Gario is a published poet and artist and a Master’s student in women’s studies at the University of Utrecht. He was born in 1984 in the former Dutch colony of Curaçao and raised in Sint Maartin. He went to Dordrecht last month wearing a homemade T-shirt stenciled with the words “Zwarte Piet is Racism,” an action that quickly led to his arrest—though when he later demanded to know why, no specific law was cited.

Gario came to the Netherlands with his mother for the first time in 1987. He says he never really noticed the Zwarte Piets during his first few years in the country, but one day his mother came home from work in shock because the receptionist had called her the office’s own “Zwarte Piet” as she entered the building. Ever since, the character has appeared throughout his poetry and artwork.

“I tell people, ‘I’m not angry. I just find it sad that you don’t know what it means and I’m here to tell you,’ ” he says. Gario began making T-shirts like the one he wore to Dordrecht and photographing people wearing them on the street and posting them to a Tumblr page.

Several weeks ago, as he stood among the crowds waiting for Sinterklaas in one of his T-shirts, Gario and a companion were approached by a police officer, who told them they would have to leave. When Gario asked for a reason, citing his freedom of speech, he says he was tackled to the ground. A video of the arrest shows Gario squirming on the pavement, repeating the words, “I didn’t do anything” as two officers hold him down.

He was pepper-sprayed and pushed into a doorway where an officer held him by the neck and rubbed the pepper spray into his eyes and nose. He was then taken into custody along with a researcher and a journalist who had accompanied them to record their presentation.

The Dutch often say they don't have a problem with race. But the way Gario (and many others I talked to) see it, in the Netherlands, race is inextricably connected to immigration—something many Dutch people do openly have a problem with, as suggested by the rise of such politicians as Geert Wilders, who has expressed a deep distrust of immigrants and has called for closed borders. (Wilders was praised extensively by Anders Behring Breivik, the man behind the Norway terror attacks.)

Allochtoon is a Dutch word for immigrants and their descendants, which means, “originating from another country.” These outsiders are accused by Wilders and others of exploiting the country’s resources and social services while not integrating properly into Dutch society.

Gario is not the only artist and activist making an issue out of Zwarte Piet. In 2008, Petra Bauer and Annette Krauss organized a march as part of an exhibition exploring the meaning of Zwarte Piet. When the media caught wind of the exhibition, the artists received death threats, and the Van Abbemuseum in Eindhoven canceled the march. Being Allochtoon, Bauer and Krauss were told they didn’t have a right to be offended by Zwarte Piet. Bauer and Krauss were shocked by how unwilling many people were to even discuss the issue. “Wilders brought our exhibit up in Parliament. He wanted to cut funding for the Van Abbemuseum for even allowing people to talk about it,” says Bauer. But Krauss says the cancelation of the march ended up being a good thing. “People who had never had said anything about Zwarte Piet started reaching out to us.”

Since the late 1960s, changes to the tradition have given the Zwarte Piets a more respectable and friendly position in Holland’s holiday theatrics. In 1968, Hoofdpiet was introduced—he is a leader in charge of all of the other Zwarte Piets—and, since that time, other Piets have been introduced as well: There is a Piet in charge of navigation, a Piet who wraps presents, and another Piet who is in charge of pepernoten cookies. Small changes in the outward appearance of the character have also been made: Earrings are no longer as common and wigs have become more curly in texture rather than coarse and frizzy.

In the past, Zwarte Piets often had a Surinamese accent and played the role of a bumbling fool. But now—during the major televised arrival of Sinterklaas, at least—one Hoofdpiet plans and organizes while another Piet acts silly, working the crowd that gathers in the streets and waits for Sinterklaas, who arrives in their wake, regally waving from his spot atop an all-white horse, wearing long cloaks and the stiff pointed hat of a bishop.

The awkwardness of this attempted shift toward a kinder, gentler Zwarte Piet is amusingly captured by David Sedaris in “Six to Eight Black Men,” first published in Esquire and collected in the book Dress Your Family in Corduroy and Denim. While the Zwarte Piets were once openly “characterized as personal slaves,” Sedaris writes, now they are described as “just good friends.”

I think history has proven that something usually comes between slavery and friendship, a period of time marked not by cookies and quiet times beside the fire but by bloodshed and mutual hostility.

It’s possible that a period of mutual hostility has now come to Holland. In the past few weeks, news outlets like the left-leaning newspaper Volkskrant have begun to cover the subject with a flurry of opinion pieces. Earlier this week, Flavia Dzodan, an activist who was born in South America and lives in Amsterdam, spoke with Latoya Peterson, of Slate’s sister site The Root, about the racism of the Zwarte Piet figure. For the moment, at least, it looks as though Gario’s arrest has helped to enlarge the conversation he and others have been asking others to join for some time.