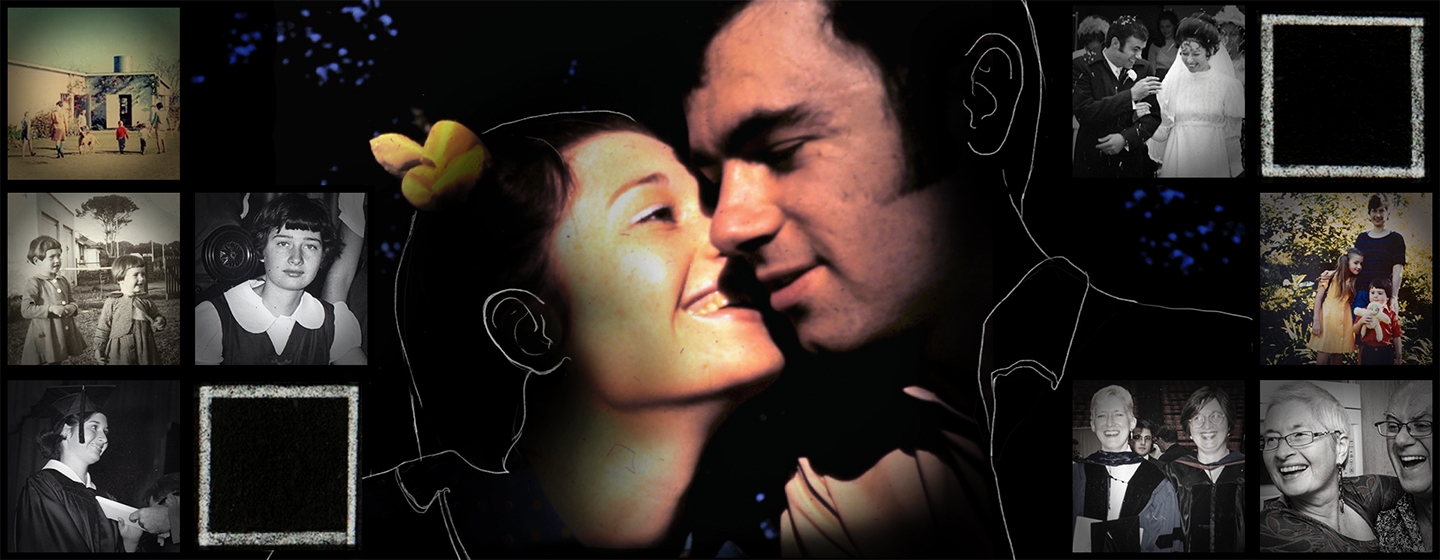

Slate is now featuring a video series about Gerda Saunders and her family as her dementia advances.

This essay was originally published in the Georgia Review, and is reprinted here with permission.

For my 61st birthday, in 2010, I was given the diagnosis of microvascular disease, after Alzheimer’s the second leading cause of dementia. I was—as my rather blunt neurologist put it—already “dementing.” Insofar as I had thought about dementia until then, I was unaware that the word had a verb form: he/she/it dements, they dement, we all dement. Yet, no matter my incredulity that this absurd verb could apply to me, now, two years later, “the cloake sitteth no lesse fit” on my chastened back.

My initial denial will seem disingenuous in light of the fact that I knew the symptoms of dementia even then—and recognized them in myself. Also, my mother had a form of mental disconnect that made her increasingly out of touch with reality until her death at 82. Given that, together with the generally known fact that dementia can run in families, why did my doctor’s utterance fall so disconsonantly on my ear?

My belated pursuit of a Ph.D. in English in my 40s introduced me to the Enlightenment philosophers. I remember being intrigued by John Locke and William Whewell’s pursuit of, as Locke puts it, the “originals from whence all our ideas take their beginnings,” a quest that took both men back to Adam’s expulsion from the Garden of Eden. Locke describes fallen Adam as lost in a “strange Country” with “all Things new, and unknown about him”; Whewell pictures Adam doing the first work of postlapsarian orientation by giving names “distinct and appropriate to the facts” to newly encountered objects and concepts.

I knew something about this project. Having emigrated in 1984 from South Africa to Salt Lake City with my husband, Peter, and our two children, I had experienced the discombobulation of having to decipher situations that must appear mundane to residents equipped with the requisite cultural vocabulary. What, for example, is one to do when an acquaintance stops by your house carrying her own beverage? How does one proceed from acquaintance to friendship without that most crucial foundation of South African hospitality, a fresh pot of tea? Why is letting your kids run naked through the sprinklers in your own private backyard or displaying baby pictures of your kids naked regarded by visitors as tantamount to sexual exploitation? What about the forlorn feeling when hosts with whom you have had a marvelous evening say goodbye to you at the door rather than walking you to your car? Yet, by my mid-50s, I had cracked these and other social codes to a great extent: I knew that having coffee meant heading to the nearest Starbucks; I had built up a scaffolding of friends so dear they had become family. Most of the time, I no longer felt like a foreigner. I had developed an American self and was settling into it. But before I had even reached my 60s, I had begun again to feel like an alien of sorts, a stranger even to myself.

I first noted a troublesome forgetting in my work as the associate director of gender studies at the University of Utah, a position I took at age 50 after a foray into the corporate world. Like the spoiler snake of the Bible, an impairment in my working memory—the ability to maintain and manipulate information “live” in a multistep process, such as remembering to carry the tens when you add numbers—slunk into my intellectual Eden.

My love of teaching was the reason I left the corporate world for academics, gladly taking a 25 percent salary cut. After less than five years in my dream job, forebodings that not all was well started to becloud my class time: Sometimes I would lose the thread of a discussion, forget the point toward which I had intended to steer the students’ thinking; often the name of a novel or author I used to know as well as my children’s names would not come to mind; not infrequently, a student would remind me during the last moments of class that I had not distributed notes or an assignment I had announced.

Even the preparation of elaborate scripts did not prevent me from losing my place in my own mnemonic system. Though I had not yet sought a diagnosis at that time, I took our program director into my confidence about my memory difficulties and she graciously supported me in negotiating smaller teaching loads. Soon there was only one class per year. During my last two years of working, I was not teaching at all. Would I have made the switch from business to the university if I had known that I would once again be bogged down in management and meetings?

On the administrative front, too, my fraying memory caused me stress. During the first gathering of a Women’s Week Committee that I chaired, I had created a detailed agenda to keep me on track: welcome; make introductions; review themes covered in past years; brainstorm ideas for this year, etc. Sometime between the welcome and the review of previous themes, my mind flipped into confusion. Someone was talking. His voice was distant, and syllables flowed from his mouth without coalescing into meaning. I panicked. I had no idea where we were in the agenda. Desperately scanning my notes, my eye fell on “Introductions.” When the speaker paused, I suggested we introduce ourselves. As the words left my mouth, I remembered that we had already gone around the table. ...

And so my downward slide continued. I knew I had to retire.

My brain: I want to retire.

Me: You’re already retired. How you do fail me! Let me count the ways.

My brain: Don’t count the days, make the days count.

Einstein: Everything that can be counted does not necessarily matter; everything that matters cannot necessarily be counted.

DEMENTIA FIELD NOTES

2-5-2011

During my going-away meeting with Gender Studies, the faculty gave me this journal. In it I’ll report my descent into the post-cerebral realm for which I am headed. No whimpering, no whining, no despair. Just the facts.

3-3-2012

Saturday at the mall I performed the physical motions of shoplifting—walked out of Macy’s with a pair of pants over my arm. I only noticed when I was inside Dillard’s on the opposite side of the mall. I hurried back, ready to explain. There were no salespeople around, and no one noticed when I put them back.

3-8-2012

Took Bob and Diane to do their grocery shopping. When we were done, I could not find my keys. The car doors were unlocked, the keys in the ignition. Returning home, I forgot to stop at Bob and Diane’s and pulled into my driveway instead. Last time I took the old people shopping, I did not notice the traffic light changing until Bea reminded me to go. She is 86.

At home, too, my various slips proliferated. I spoke to my family and closest friends. “Senior moments,” my peers knowingly declared. Even my then-twentysomething children, Marissa and Newton, assured me they, too, experienced similar lapses. As the incidents accumulated, though, my immediate family acknowledged that they noticed a change. By the time I approached 60, they agreed that my deficits might be adding up to a diagnosable disease. I started considering a doctor’s appointment, my mother’s mental unraveling never far from my mind.

On a February day in 1996, my mother, Susanna Catharina Steenekamp, was found wandering in her retirement center in Pretoria, severely disoriented. When I arrived in her hospital room days later, she did not seem aware that I had come halfway across the globe. However, she did recognize me—if I were to take as proof that my utterly proper mother introduced me to her nurse as “my daughter who writes fuck,” an apparent reference to the language in my short-story collection. Susanna also announced her every bodily function, saw angels, and poured water over herself “to bring down my temperature.” With family, her loving disposition still came through, but with the black nurses her post-apartheid liberalism evaporated. She acted superior, entitled, rude. Could this really be the woman who, as a young social worker, had accepted a Cape Colored client’s invitation to climb into her bed to warm up her feet?

Despite Susanna’s altered behavior, only my brother Boshoff, himself a doctor, mentioned dementia. Nevertheless, like our mother’s doctors, he did not push for an official diagnosis, instead advocating that her behavior determine the intensity of assistance she would need. And that is how her second childhood played out without a name.

To accommodate the need for a high level of care, my sister Lana put our mother’s house up for sale, disposed of her furniture, and found her a private room in an “old-age home” that provided the 24-hour care she needed. Surprising us all, my mother came out of her deranged state within a year after her dramatic collapse. When Susanna “came to,” she resolutely refused to stay in a place that afforded her no freedom or privacy. Lana reinstalled her in her previous house, which fortunately had not yet been sold.

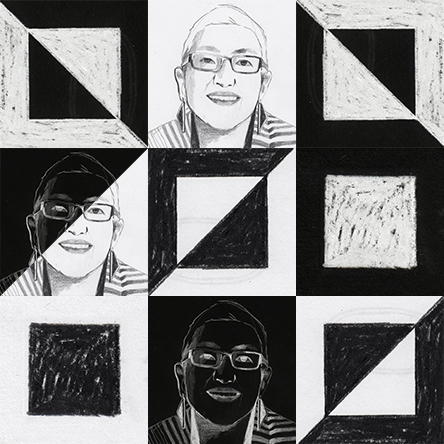

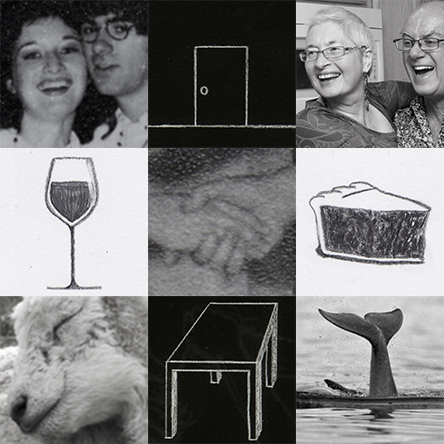

Photo courtesy Gerda Saunders

Back in her own home, Susanna frequently fell, often injuring herself; she had trouble cooking—she was once discovered eating meat that was still raw. Her nurses suspected she was having a series of small strokes. Confronting her deteriorating condition, she began keeping a dagboek, or “day book,” as Afrikaans has it: “I walked throughout the sick time for exercise.” “I slept through the afternoon for the lack of inspiration or initiative to do something better.” “My illness brought the finality of things, events strongly to the fore. Is that what is crushing me?”

All the while, Susanna’s functionality was declining to a point where it was clear she was incapable of living by herself, even with the help of a house cleaner/companion twice a week, the watchful eye of the center’s staff, and the option to have three meals a day at the communal dining room. Lana moved her to an old-age home with levels of care ranging from semi-independence to lockup.

Susanna would be moved several times more during her remaining years. In each of the centers to which various circumstances (her health, finances, restlessness) took her, Susanna received personal attention of a quality that only well-off Americans can dream of. Nevertheless, her writing shows that, for most of the rest of her life, she felt lonely, distanced from other people, and frustrated about not being able to keep busy. “I am only able to revive the appearance of earlier times with much effort: the hobbies are having trouble getting started, the housekeeping is geared only to the most necessary, and people are few and difficult.”

My mother’s deterioration had gone without a name. What, then, to do about my own unhinging? Preliminary research confirmed what Peter and I had learned anecdotally: Although medications might slow the progression of Alzheimer’s and other dementias, they could not stave off the inevitable decline that catches up with even the most diligently monitored and medicated patient. Moreover, we were afraid that the quest for diagnosis could trap us in what writer and physician Atul Gawande once described as “the seemingly unstoppable momentum of medical treatment.” Still, we are both the kind of people who want to know, always drawn like moths toward enlightenment. Also, confirmation of our suspicions might help us prepare. If the unnamable loomed ahead, we could plan for expensive care, diminished quality of life, and a way to end my life at the right time.

I asked Peter to come along for my doctor’s appointment. Our primary care doctor politely entertained our doubts about the value of diagnosis. She heard out our pontifications about what we regarded as a worthwhile quality of life, and let us stew our own way into following her suggestion that I have an MRI. The scan results showed “white matter lesions”—an indication of clogged microvessels that prevent blood from reaching nearby brain areas. Dr. Eborn confirmed the Internet wisdom that microvascular dementia might benefit from cholesterol- and blood pressure-lowering medications to retard the clogging. However, a neurologist would first have to confirm a connection between my memory problems and the lesions.

One neurologist, one neuropsychologist, dozens of tests, and many hundreds of out-of-pocket dollars later, my neurologist delivered the D-word. Given how early I noticed my symptoms, she projected that two more neurological evaluations at two-year intervals would be needed before I would officially meet the criteria of dementia.

But in my heart I already knew: I am dementing I am dementing I am dementing.

REFLECTION ON DEMENTIA FIELD NOTES OF 5-14-11

Now that your grandson Kanye has abdicated the portable crib, his sleepovers require more adult accommodations. Accordingly, you are on the hunt for a sleeping bag. Not the Disney-derived kind, wraparound promoters of consumerism, of which, moreover, the fabric is slippery enough to slide, child-and-all, from futon to floor. You want a proper sleep sack, commercial-free and stay-put. Tilting at this newfangled windmill, you set out for Ikea. Before leaving, you study your Google map enhanced with Peter’s penciled-in notes. You are Doña Quixote preparing for a quest.

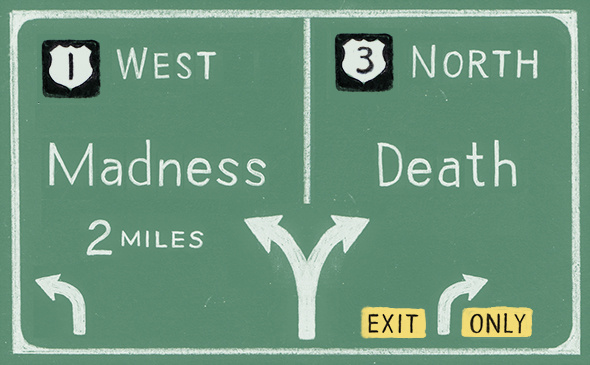

Illustration by Lisa Larson-Walker

You conquer the I-15 onramp. Eyes peeled, you watch the exit numbers fly by. Ikea is just a few exits south from Newton and Cheryl’s. Next weekend they’re bringing the grandkids for a sleepover: 1-year-old Aliya all red-cheeked in her head-to-toe onesie in the crib, 4-year-old Kanye snuggled on a mattress in whatever you’re going to find and buy today, maybe something like the quilt you stitched for Marissa by tracing her body on butcher paper.

Damn, you missed a mileage board! You fix your gaze on the tarmac, proceed with gingerly premeditated glances to the side. Suddenly you realize that you have forgotten the number you are supposed to be looking out for. You probe the passenger seat for the instructions, bring the paper level with the top of the steering wheel, snag the number, repeat like a mantra. YES! Only three exits to go. This place has only three exits, sir: Madness, and Death.* As for me and my house, we shall shop. Ah, those red bed lamps you found when Marissa came back from South Africa.

What else is there to say about the chivalric excursion of an hidalga whose brain dried up from too much reading? You will never know whether you indeed took the wrong exit or whether it was the road-works detour that deposited you beside a field dotted with horses, sheep, and winter-gray hay bales. The horse that limped away from its more youthful companions and stopped by your car was the perfect Rocinante to your Doña Quixote. Eye to eye, the two of you contemplated the way home.

You remember the winter rescue of a pod of beluga whales trapped near a Chukchi village off the Bering Strait. It was during your family’s first new year as sojourners of the Northern Hemisphere. Surrounded by 12-foot-thick ice, 3,000 white whales took turns breathing in a few remaining unfrozen pools. The ocean was beyond their reach, receding as the ice advanced.

Many weeks after the villagers had radioed for help, the icebreaker Moskva cleared a channel to the ocean. Weak and bewildered, the whales fed in the larger pools the Moskva had made. After gaining strength, they started frolicking to what 1820s explorer William Parry had described as “shrill, ringing sounds, not unlike that of musical glasses played badly.” They swam and they ate; they clicked, yelped, chirped, whistled, and trilled. As Izvestia wrote in despair, they did everything but pursue their escape along the newly gouged canal. At last someone recalled that whales react acutely to music. The ship’s gramophone was fired up. Russian folk dances, martial fanfares, and classical crescendos poured off the deck. While the patriotic strains left the whales nonplused, the classical music did the trick. The herd began to follow the ship.

Unexpectedly a character from graduate school, literary critic Harold Bloom, strolls into your field of stagnation. Scratching the suborbital depression between Rocinante’s eyes, he remarks, Don Quixote can remain a hero only as long as he retains his crazy will to be himself, as long as he keeps up the war against Freud’s reality principle.

If remaining yourself means you must fight reality, you decline. You, Gertruida Magdalena Saunders, must live and die by reason. Fact is, you have no idea how to retrace your path home along the “longicuous” moonscape pockmarked with half-a-dozen “scattered bifrontal lobe nonspecific white matter lesions.” And you know that in this reality, no Moskva will materialize for you.

So: You call Peter, cry a little bit, and follow his voice home.

DEMENTIA FIELD NOTES

8-24-2011

I could not combine the up and sideways movements of our bathroom tap to make cold water come out. Instead fetched cold water from the kitchen in the plastic jug.

5-16-2012

At La Frontera I was unable to interpret the beer stein the server put before me. I knew it was a beer stein, but couldn’t absorb the fact that it was upside-down. I saw it as right-side-up with a tight-fitting glass lid, which I tried to take off. I asked Peter how to get it off, and he turned the glass around. Then I understood. We were with friends.

5-24-2012

Here at the vacation house in Zion National Park I have trouble reading the diagram for the stove plates. I meant to switch on the kettle and instead switched on the pan of oil. Fortunately Newton saw it and prevented a disaster.

Photo courtesy Gerda Saunders

* * *

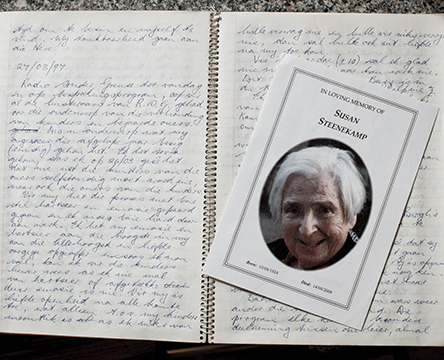

I found my mother’s Day Book in her room after her death in August 2006. It is a spiral notebook with 27 entries in longhand, dating from the beginning of March through the end of April 1997. Though Susanna had given me copies of several earlier writing projects, including a 1995 meditation on her life, neither I nor any of my siblings knew about the Day Book, which she wrote in Afrikaans. Her rendition of mere facts, though, is not where the journal’s riches lie: Rather, she offers an echo of her hopes, her bravery in the face of vanishing capacities, her beneficent view of people, and her love for family. There are multiple entries referencing another memoir she was writing on her computer. In her Day Book she reports and bewails false starts and lack of progress with this effort to write her life story electronically. After her death, nobody knew to look for evidence of that book on her computer, which was given away with the rest of her personal belongings.

SUSANNA’S DAY BOOK

3-8-1997

My heart does not come to rest.

3-11-1996 [sic]

I have started thinking seriously again that I have for years wanted to write an uncomplicated book without big words or much learning. Would I be able to do that? I will try. The least is that I will have a book to my name. Most importantly, it will create an activity here in my retirement center where I spend most of my time alone. In any other private house I would have been alone too.

3-17-1997

In all my hobbies [painting, sketching, reading] I was well away when I became ill last year in early February; after my illness, however, I could not even write my name or write as I’m doing here now. What used to be everyday things had to come back gradually.

3-20-1997

The society in which we and our children find ourselves provides for the care of children from when they’re small, adults work the whole day, old people are rightfully taken care of in retirement and old-age homes. However, what about the wherewithal of which loneliness snips the wings? Or those like me, who “struggle to keep busy,” if one can even call that an activity? When I am not busy, I am lonely.

3-21-1997

Life outside me has become too new and strange and fast. The time will come when I will be focused only on my bodily needs.

3-27-1997

Radio without Borders had an open discussion today on the relationship between children and elderly parents. This topic has kept me busy (seriously) for the past year. I have come so far that I say not only the children have to become independent from the parents, but also the parents from the children.

For me this process was accompanied by much quiet heartsoreness and emotion and I had to work very hard at it. I gave my emotion and heartsoreness over to the most holy in myself and to the Holy of Holies, since I feel I can love the children more when I am not mad with heartsoreness or distracted by emotion. To me love is openness in every direction, and in respect of my children this is only possible if I expect nothing from them and blame them for nothing—then they will come to me out of love.

Dementia is a catchall term for various disabling problems with memory and thinking. Although the end results are very much alike no matter the cause of a particular dementia, diagnosing a cause helps establish a timeline and whether any medications are available to slow the progression.

The Alzheimer’s Association defines 13 different types. Alzheimer’s, which for most people is synonymous with dementia, is the most common. It is caused by deposition in the brain of plaques (misfolded amyloid protein) and the presence of tangles (an abnormal number of protein tubes). There are no biological tests yet to definitively diagnose Alzheimer’s in a living person; plaques and tangles are found in the brain only at autopsy. A clinical diagnosis is made by excluding other forms of dementia and rating the patient on two different scales, one that measures cognitive decline, the other functional decline.

Vascular dementia, which I have, results from the blockage of blood vessels in the brain, which can be detected on an MRI as lesions. These blockages eventually lead to repeated strokes. Some strokes cause immediately evident damage, but others are “silent” and not noticed by the patient or her caretakers when they happen.

Despite the different origins of Alzheimer’s and vascular dementia, their outcomes are similar enough to be assessed by the same two seven-stage scales: 1) the Global Deterioration Scale for Assessment of Primary Degenerative Dementia, or GDS, and (2 the Functional Assessment Staging Tool, or FAST. Both are widely used in the medical and psychiatric community. The GDS targets the level of damage in memory and thinking; FAST assesses an individual’s functioning and everyday self-care activities. Each scale ranges from stage 1, in which no cognitive deficits or odd behavior are noticed by either the patient or her loved ones, to stage 7, in which very severe cognitive and functional decline are evident. Stage 7, also known as late-stage dementia, is characterized by the deterioration of the patient’s speaking ability to about a half-dozen intelligible words, combined with progressive loss of the ability to walk, sit up, smile, and hold up her head. Thus, any particular person’s dementia falls somewhere between mild impairment and Bedlam-style madness.

But one’s dementia does not lie where it falls. As sufferers of dementia (and their caretakers) soon discover, medical professionals’ use of the present continuous form of the verb “to dement” is highly significant. Even stage 7 patients are always still dementing, never done. Until they die.

REFLECTION ON DEMENTIA FIELD NOTES OF 11-7-2011

Retired University of Utah faculty still have library privileges. Tracking down your wish list along the library’s boustrophedon of call numbers, you also cherry-pick their next-door, upstairs, and downstairs neighbors: Michael Paterniti’s Driving Mr. Albert: A Trip Across America With Einstein’s Brain; Jonah Lehrer’s Proust Was a Neuroscientist; Barbara G. Walker’s Feminist Fairy Tales; Edith Grossman’s new translation of Don Quixote, with an introduction by Harold Bloom; René Daumal’s A Night of Serious Drinking.

Setting out for home along the route you drove to school and work for 20-some years, you float across the familiar suburb-scape, bobbing as leisurely as Einstein’s brain in a Tupperware bowl in the trunk of a Buick Skylark. As you stop for a pedestrian crossing, your mother tongue asserts itself: zebra oorgang. Why did the zebra cross the solar system? Because it was immortalized as an image on the gold-plated disc affixed to the 1970s Voyager spacecraft, launched along with greetings in 60 human languages and the calls of the humpback whales.

Observing the orange-flag-wielding pedestrian, you think, “Whether the zebra crosses the road or the road crosses the zebra depends upon your frame of reference.” Einstein’s topsy-turvy universe. Like the one in which you suddenly find yourself. But yours is not comfortingly galactic. Uncanny, rather. You have stepped into a View-Master reel—“Hansel and Gretel”? Your cousin’s Don Quijote de la Mancha with its tauntingly inexplicable foreign subtitles? Trees arch overhead. Stage left, a cottage slouches behind the trunks. Are you going east-west or north-south? Are these the trees near the gas station where you turn west, or the foresty tunnel you enter after already having turned? There are no street signs. The birds have eaten your breadcrumbs.

In the rearview mirror you note cars backed up behind you. Dear Professor Einstein: I understand the world moves so fast, it in effect stands still. A honk from the vehicle on your heels sets the others off. You cede the road, sidle almost onto the sidewalk. Part of the time it seems a person is standing right-side-up; part of the time, on the lower side of the world, he stands on his head. And part of the time he sticks out at right angles and part of the time at left angles. The aggrieved drivers pass, bestowing dirty looks. You sit with the engine running, waiting for—what? Baba Yaga in her speeding mortar fixing to scoot you along with her pestle? The Moskva?

Something from a witch’s cauldron rises up your gullet. From your face, emotions sprout in warty patches. I’m going to devour you alive. Your brain has dried up. You’re a space cadet. The European Space Agency will soon launch two spacecraft, the Hidalgo and the Sancho, to divert asteroids hurtling toward Earth.

An approaching semitruck blasts its troll breath from its overhead exhaust pipes, reminding you that the windmill you face is neither the size of Manhattan nor celestial. You have a scientific bent. Continue along this street and you will recognize something sooner or later. You are Doña Quixote crossing the equator in the Enchanted Boat. You are big Nanny Goat Gruff confronting your inner troll. Up you jump. You take a gap in the traffic, speed up like someone who knows where she’s going. Soon the landscape will shift and you’ll say, “Ah, there are those two houses with xeriscaped gardens right next to each other.”

For a while, Anytown, USA, keeps rolling by. But finally—a boxy two-story building differentiates itself from its lookalike neighbors: the dentist where Newton had his wisdom teeth out. Trip-trap, trip-trap. Just half a block to the Sizzler. Up goes the troll. He goes SPLASH in the water. Right angle, 10 blocks to the light on 300 East. Big Nanny Goat Gruff is over the bridge. Left angle at the light, right angle at the blue house, right angle at Amit and Ruchika’s. The Nanny Goats Gruff have fun in the grass. They eat and eat. We like it here, they say.

You stack the library books next to your two-seater La-Z-Boy couch. La-Z-girl, excuse me! You sink into your side, lever up the footrest, cover your knees with the blanket Peter’s mother had crocheted. Like Proust’s madeleine, this memory is but regret for a particular moment; your mom-in-law’s treasured handcrafts are as fugitive as, alas, the years. Your hand greedily clamps the top two books from your hard-won stash. You think of Albert Einstein’s mother when his teachers announced the boy was too stupid to learn. She had him begin violin lessons. Remembering her later in life, he would say, A table, a chair, a bowl of fruit, and a violin; what else does a man need to be happy? Before you settle on which book to open, your eyes fall on Peter, who is working on his laptop at the table.

Would it be reasonable to assume that falling in love is one of the stupid things one does while sticking out upside down on the bottom of the earth?

Sincerely,

Frank Wall

Dear Mr. Wall, Falling in love is not at all the most stupid thing people do, but gravitation cannot be held responsible.

Sincerely,

Albert Einstein

* * *

After my retirement on Aug. 1, 2011, I needed almost six months to feel ready for what I had looked forward to for most of my working life: preparing an almost-done novel for publication and completing a second one, into which I had already poured years of time and research. However, my last years at Gender Studies had left me fearful that I might not be able to edit a 300-page novel and resume another; at work, writing had come to drain my mental energy to the point where I had none left for my family or home life.

Just about every aspect of my university job had involved writing. The program emails, office circulars, meeting reports, letters of recommendation, and other official letters had been quite doable just about up to the time of my retirement—they were relatively short, self-contained pieces. However, longer, research-based documents—which I used to love—had become very, very difficult. As fate would have it, a major responsibility during my 62nd year would be just such a piece of writing: a policy and procedures document creating a new position in our program. The document had to be written in the legal language and style of the university’s Policy and Procedures Manual; it had to include references to applicable university rules; and it had to align with the goals and practices of the various colleges and departments with which our program jointly appointed faculty. Given that this manual runs to hundreds of pages and that my short-term memory already seemed to barely function, I had to contend with the fact that a mere switch between screens erased from my mind the item I was researching. Accordingly, I wrote down, in longhand, what information I needed before switching screens. Once I had electronically copied the answer, I used the same process in reverse, jotting down keywords so that I would know what to do with the information once I got back to the draft screen. And so on for the bulk of the academic year. Work, for me, had become unconscionably time-consuming and stress-provoking.

After thinking about my retirement writing projects for a month or two, I decided against revising my books-in-progress. I instead started writing an essay about the changes with which I am struggling as the result of my developing dementia. Then I wrote more. Could I possibly keep writing well enough and long enough for the accumulating essays to become the chapters of a book?

DEMENTIA FIELD NOTES

7-10-2012

When I went to a pre-check for my colon surgery, I parked between an SUV and a shoulder-high wall. When I returned, someone was waiting for my parking spot—but too close. I waved her back, she retreated—but not enough. I motioned again, she moved another inch. Still feeling cramped, I reversed. When I turned I went bang into the SUV. I got such a fright that I reversed and hit the concrete wall.

I wrote the SUV owner a note, called Peter. I told him our car was OK and I would drive back.

Bottomless dread.

Back home, I told Peter I was no longer going to drive. Because it was the day I usually took our elderly neighbors shopping, I went over to tell them I would not be taking them that day or again in the future. I could not bring myself to tell anyone else. It wasn’t so much the actual driving, but rather the change in what I think of as a core of my self: helping other people.

7-16-2012

On Saturday morning I made a statement about not driving: I went shopping. By bus. At Fashion Place Mall. An hour there and an hour back on weekends. Nothing like being one of the elite on the bus who are not toothless, homeless, in a wheelchair, or on oxygen to take my mind off myself. Nothing to make my troubles seem trivial like the disproportionately large number of African-Americans, Native Americans, and Hispanics awakening my post-immigration guilt about still being racially privileged.

In time my better-than-expected (albeit painfully slow) progress on my book about dementia—from which this essay is derived—became its own puzzle. Looking back at the chapters I’ve completed, I ask myself, “How come I can still write? Could I be faking dementia?” Since the indignities accumulating in my ADLs as well as conversation-inhibiting lacunae in my speech are classic markers of early dementia, the discrepancy between those failures and my preserved writing ability must be part of my story too.

When I betook myself to my doctors, my friends, and the Internet, I found that I am not the only person who appears to be “faking.” For example, a counselor friend tells of a retired philosophy professor from her alma mater who can no longer bathe, dress, or feed himself, but directs canonical philosophy discussions with visiting former colleagues. A sprinkling of peer-reviewed neurological research, too, reports the “unexpected preservation of a cognitive function in individuals with dementia”: in the neurology journal Brain, for example, researchers Julia Hailstone and Rohani Omar present the case of a 64-year-old semiprofessional harpsichordist with a non-Alzheimer’s dementia who “had virtually no comprehension of oral or written language,” “was mute,” and did not understand the functions “of objects such as a corkscrew and a tuning fork,” but nevertheless demonstrated “the motor skills required in playing [his] instrument,” “the visuoperceptual skills required to read scores,” and “the cognitive skills involved in interpreting symbolic notation” as attested by his performance of “technically demanding, structurally complex compositions in an expressive manner.”

During my search for accounts of the experience of dementia, I also came upon David Shenk’s bestseller on Alzheimer’s, The Forgetting. During his research Shenk discovered Morris Friedell, a sociology professor diagnosed at age 59, whose final year of teaching, four years before his diagnosis, sounds uncannily like mine.

[H]e began to have trouble remembering what his students said in class. Later, he couldn’t remember a conversation he’d just had with his mother. At the neuropsychologist’s office, he couldn’t tell the doctor about a movie he’d seen just the night before. They ran the usual tests. He got a perfect score on the MMSE [Mini Mental State Exam, a test done in the doctor’s office that includes determining the patient’s orientation to time, ability to repeat three unrelated words right after the tester has said them, naming objects, and reading and following instructions]. On the brain scans he didn’t fare so well.

After a year of long-distance interaction, Shenk met Friedell in person at an Alzheimer’s conference at New York University, where Friedell did a poster presentation titled “Potential for Rehabilitation in Alzheimer’s.” During lunch with Shenk the next day, Friedell explained that for him rehabilitation no longer means “Intensive rehab, in the spirit of what knee and hip surgery patients go through,” but rather “minimizing and slowing the cognitive loss by adapting to it.” His method includes performing an extremely simple task “just to get into a confidence mind-set,” and from there taking on the challenge “to solve problems in new, simpler ways.”

Illustration by Lisa Larson-Walker

After lunch, Friedell asked Shenk whether they had “ever spoken before today.”

So, it seems that dementia can sometimes go like this: Persons having spent a lifetime mastering particular knowledge structures and intellectual skills may retain access to this expertise even after becoming utterly dependent on others in living their lives. I want to believe this will be my story, too. But in truth writing is getting slower and harder: This essay took nine months to create; the four chapters in my book project from which it originates took two years of many eight-hour days, reams of notes for switching computer screens, endless thesaurus-mining to pry almost-there words from the tip of my tongue, scissors-and-tape cutting and pasting to figure out how a single comprehensive piece might come together, and the tough-love edits of writer friends Shen Christenson and Kirstin Scott.

As I completed each chapter, I made it confidentially available to friends and family as a means of updating them about my health and state of mind. Many recipients asked if they could pass the chapters on to people in their circle who were in some way affected by dementia. My readers’ feedback brimmed with extraordinary compassion, but also, to my surprise, gratitude. Hearing about the disease from the perspective of someone who actually has it—albeit its early stages—added a voice they had not found in other stories about dementia, namely those told by the caretakers of sufferers much further along the scale of diminishment. A peek into my experience, they said, helped diminish the fear and stigma engendered by the disease and additionally gave them insight into the often inexplicable behavior of the people they love who have dementia.

While these responses encouraged me to complete the book, my frustratingly slow progress reminded me that I might not be able to do so. As an interim measure, therefore, I decided to write a shorter piece that I hoped might reach people beyond my inner circle. The result is this essay, a reshaping of book excerpts related to the most formidable issue I face: my ever-changing identity.

Dementia can also go like this: A person having spent a lifetime mastering particular knowledge structures and intellectual skills—a well-educated person, in other words—may for a while use a “greater ‘thinking power’ ” to compensate for the disease in its early stage. However, as Mail Online reporter Jenny Hope brought to light, research done at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine of Yeshiva University shows that once university graduates’ dementia becomes evident, they “suffer a memory decline that is fifty percent faster than someone with a minimal education.”

My father: Your education is something you can always fall back on.

My mother: Dreams are easy, but the gander lays the egg.

Einstein: The faster you go, the shorter you are.

DEMENTIA FIELD NOTES, ELECTION DAY 2012

Illustration by Lisa Larson-Walker

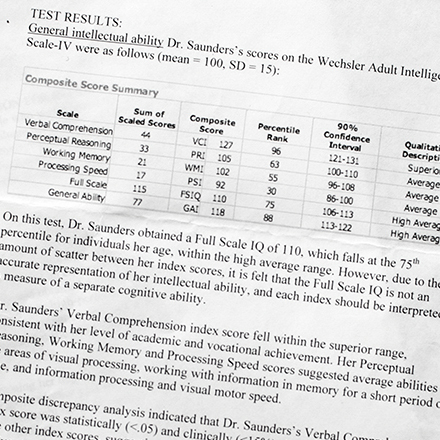

Not only for Obama was this a red-letter day. Two years had passed since my first neurological evaluation, and I went for my second one today. Taking the test felt better than I thought it would. I think I did better than last time on the portion where I have to remember 16 words after various distractions, since I knew from the beginning to listen for categories. After my two-years-ago test, the words had compulsively played in my head for weeks. My neuropsychologist, Dr. Janiece Pompa, remarked that my long-term memory was clearly still in good repair.

After the test, Peter and I updated her on the happenings of the last two years: my difficulty with multistep tasks such as cleaning the kitchen counter, speech failures, tendency to get lost, inability to follow instructions from the GPS, and the accident that made me give up driving. I also told her about my essays. She asked about my method of research, and I explained the longhand-note thing. When I told her about the “faking” and that my friends don’t see the laborious writing process and the hours and hours and the confusion, I got quite emotional.

Peter talked about my increasing forgetfulness, but noted that I get the overall picture of a situation very well. I confessed to being selfish in claiming so much writing time, and Peter confirmed my obsession. He added that I had always been a little like that when writing. I said I’m racing against the clock, which justifies my selfishness to myself; when I tell Peter I’m racing, it feels as if I’m blackmailing him because it makes him sad and then he wants to do just anything to make me happy. He acknowledged that it makes him sad (got a bit teary himself) but said it wasn’t all that bad.

I divulged the difficulties I’m having with my heavily research-based piece “Your Brain on the Fritz” and that it takes me much longer to see what should be in and what should be out to make the chapter cohere—that I have to physically cut and paste multiple times. ...

Now we have to wait for the detailed results to come in the mail.

* * *

The final entry of Susanna’s Day Book—the one I previously mentioned—is the only one with a title: “Die Ware Jakob,” or “The True Jacob,” an Afrikaans expression for “The Real Thing.” The entry was intended to replace her many computer-written false starts on the memoir she had mentioned, her intended “justification” of her life. At the time of this last entry, she had apparently lost all her electronic work on the computer. While awaiting help to relocate her files (which she feared she might have erased accidentally), she wrote a longhand “true beginning” of her memoir. Her writing stops midnarrative. She never again wrote any prose we know of—only her name.

The 27th and final entry differs from the previous ones in several respects: Susanna writes on every other line of the ruled page, whereas she did not skip lines before—and on this one day she wrote one-quarter of the words in the entire Day Book, whereas the other three-quarters were attained over almost two months. Given that this section maintains an average of only three words per line compared with five-and-a-bit before, the writing seems fevered—the spacing and orthographically drawn-out words reminiscent of my own long-ago blue book exams. The content, too, is atypical. This entry alone is devoted entirely to her illness.

DIE WARE JAKOB

4-28-1997

The illness last year from beginning February to the end of October and everything I associate with it—which proves that it did happen—will not leave me. Whether I deny it or whether I affirm it or whether I just let it be ... it drags behind me like a specter, is always with me. ... The dreadful anguish and shock when I realized I would have to live in an old-age home for the rest of my life left me with a fragile heart. Life would never get better.

The night before the onset of the illness, I was working on a painting, inspired and enthusiastic: it was a natural scene, like heaven might have looked like, with beautiful plants, flowers, birds, insects, a lizard, and a snake.

It was late when I went to bed and during the night I saw a vision of heaven. Now, for the first time, I think it could have been a dream with a remnant carrying over into the next day like the painting I had made—however, initially I was convinced that it was a vision, a hallucination! This insight makes me feel a lot better. A hallucination sounds much sicker than a dream. ... Nothing will persuade me now that it had not been a dream!

Now with the telling I realize that I cannot remember the chronology well at all: I came back home from the hospital, but I don’t know if I stayed at home. I know I was back at the sick bay, because I got into trouble for wetting the floor. I did it to bring down my body temperature. Something I had successfully done at the Little Company of Mary’s Hospital, but on a smaller scale. Back in the sick bay I started getting confused. Or had it already happened at my home?

Even though I have been able to return to my house, the heartsoreness is deeply lodged and I connect it to more and more things. I have the horrible feeling that I was not as sick as it is alleged and that I could have been spared all the trauma of moving. I want to know why I could not just as well have been sick and mixed up at home and have recovered here?

I suspect I must have been ill, since I was so totally dependent and submissive that I did everything I was told.

DEMENTIA FIELD NOTES

02-16-2013

My test results came in the mail while we were in Chicago to help Marissa and Adam stock the freezer and wash the baby clothes in time for the baby’s birth. Back home, I found the neuropsychological report in the huge box of mail our neighbor Diane had collected for us. I read the neuropsychological report, but could not bring myself to write anything about it until now—over two weeks later.

Photo courtesy Gerda Saunders

Right after the test, while debriefing with Dr. Pompa, I had great confidence in the outcome of the working memory test, the one where I had to remember the four sets of words. During my test two years ago, I had demonstrated only “average learning ability.” Since I had learned during that test cycle that the 16 words came in semantic clusters, it felt as if I were doing better the second time round. To my disappointment, though, the results show that my overall score this time was worse than at age 61.

The report’s fine print explains my lower overall score. Even though I knew the words came in four categories, after most repeats I could remember only three categories. I remember saying, “I know there is one I haven’t said yet,” but could not come up with what it was. Together with the missing category all four of its words were lost. And this had been the section for which I’d had the highest hopes.

In the other sections my score had not gone downhill as much as I had expected from how challenging they felt during the test. In the connect-the-numbers and build-the-diagram sections I had not made many mistakes, but my slowness lowered the scores. After I had struggled through those sections, Dr. Pompa must have seen how demoralized I was because she hinted that I might not want to do the math test this time. I was happy to leave it out. The report of two years ago already attested to the sorry state into which my math skills had slipped.

What unnerves me most in both sets of test results, though, is the drop in my IQ since my last high school test. In my day, South African schools used the Wechsler scale, which is the same as the one Dr. Pompa used. The results are therefore comparable. And the drop in my number precipitous.

Even though I know that IQ is nowadays regarded as too simplistic a measure of anyone’s achievement potential and only tangentially related to life success, my IQ had always mattered to me. It stood for the academic prowess for which I was recognized as long as I can remember. It was something good I knew about myself like my tallness and good skin and ability to stay calm. Now my IQ has become one of those things I have acquired over time that I don’t like: my sagging jowls, my slight limp from an old foot surgery, my wandering attention.

Until I have made peace with myself about this, I cannot talk about it to anyone. Not even Peter.

Sitting on her 12-foot-high, strong, long arm of a cottonwood tree, Doña Quixote is trying to see life as it would be if only she were the uppercase Someone in charge of the Holy Headquarters from which justice is supposedly administered. She giggles at the thought that in Afrikaans hoog in die takke, “high up in the branches,” means that you are intoxicated. She isn’t. To remedy this, Winston Churchill, who used to start his day with a snifter of brandy warmed by his butler over a candle, wobbles her branch with his 22 stone. “Sir, you are drunk,” she prissily informs him. “Madam,” Churchill rejoins, “you are demented. In the morning, I shall be sober.” Now if Doña Quixote were indeed the uppercase Someone in charge of the universe, she would rather have had Churchill pronounce her as a faker and have that be true.

Although in real life Doña Quixote is manifestly deficient in uppercaseness, she nevertheless assumes the omnivoyance required to exchange a wink with Einstein’s eyes. Those eyes, their genial brown leached to pond-water drabness by a four-decade-long alcohol bath, are in the New York City safety deposit box to which Dr. Henry Abrams, the physicist’s ophthalmologist, consigned them after removing them from the genius’ still-warm body because they were part of the brain too, and I wanted a keepsake. Another keepsake-hoarder, Dr. Thomas Harvey, squirreled away two potato-sized chunks of the genius’ brain after completing the autopsy. The rest he sectioned into 170 die-sized blocks, handfuls of which he magnanimously dispatched to cronies.

In 1995 journalist Michael Paterniti learned that then-84-year-old Harvey still “owned” the relics. Paterniti invited Harvey on a trip to California, the ticket to ride being Einstein’s brain, which they would jointly deliver to the physicist’s adopted granddaughter, Evelyn Einstein.

Exploiting Einstein’s dictum that the distinction among the past, present, and future is only a stubbornly persistent illusion, Doña Quixote listens in on the travelers’ banter as they barrel across the plains. Is it true, Paterniti wants to know, that Evelyn was told as a child that she was actually Opa Albert’s lovechild, but that her half brother Ernst, who had now become her Vater, nevertheless loved her sehr viel? Harvey demurs that all he really knows of the genius is the architecture of his brain. Did Paterniti know that Das Brain was endowed with a sehr robust inferior parietal lobe whose size exceeded those of ordinary mortals by 15 percent?

Harvey’s factoid bounces between Doña Quixote’s prefrontal cortex and temporal lobes, dislodging a reference datum from neuroscientist Michael Gazzaniga’s Who’s in Charge?—to wit, the inferior parietal lobe is where the brain makes up explanations when it actually does not have enough cues to understand a situation.

From the Buick’s passenger seat, Thomas Harvey weighs in: “Not so fast, Frau Quixote! What Das Brain had gained in confabulation was counteracted by its lack of a parietal operculum ... ”

Neuroscience pioneer V.S. Ramachandran, who is eagerly anticipating Das Brain’s arrival in California, interjects his own scoop: “ ... and therefore it had no Broca’s speech area to deploy words in a grammar that produces meaning.”

Doña Quixote’s heart lurches toward poor young Albert. No wonder he hardly spoke during his early youth! Das Brain, too, musters enough mirror neurons to beam empathy: For didn’t der poor Junge make Das Brain practice a sentence for hours before the boy dared mutter it, causing Vati and Mutti to fear their son was retarded? That is—Das Brain’s amygdala flares relief—until that exhilarating moment when Albert, 9 years old, suddenly became decidedly eloquent:

Albert: The soup is too hot.

Mutti und Vati: Why didn’t you say anything before?

Albert: Because up to now everything was in order.

What a hilarious child, Doña Quixote thinks absently. Her mind has drifted along a sideways rivulet of awe at her own hubris for having managed to insert the most iconic left brain in history into a story that is really about herself. Of course, it is not young Albert whom she fears is too stupid to learn.

Further down the limb that braces her against gravity, the rope remnants of a backyard swing coil to life—Eve’s evil snake, snarkily hissing the syllables that drove her up the tree: “Tessst resultsss.” She should really go home with the news that she had lost more than 20 IQ points since she was last tested in her late teens.

Never done. Until you die. My heart does not come to rest.

The branches above her shiver, and through the rustling leaves pops Churchill’s bulldog head. Let us reconcile ourselves to the mysterious rhythm of our destinies, he says, sounding a bit like Einstein, such as they must be in this world of space and time.

Doña Quixote accepts the snifter the British Bulldog extends through the dull undersides of the leaves as he offers a toast: “To the god who plays dice.” She sips.

Other confabulators tilt their cups in a salutation:

Proust: Here’s to my friends wherever there are companies of trees, wounded but not vanquished, which huddle together with touching obstinacy to implore an inclement and pitiless sky.

Susanna: The angels and the people sing hymns of praise. Who are angels and who are people? Hosanna! Hosanna!

* * *

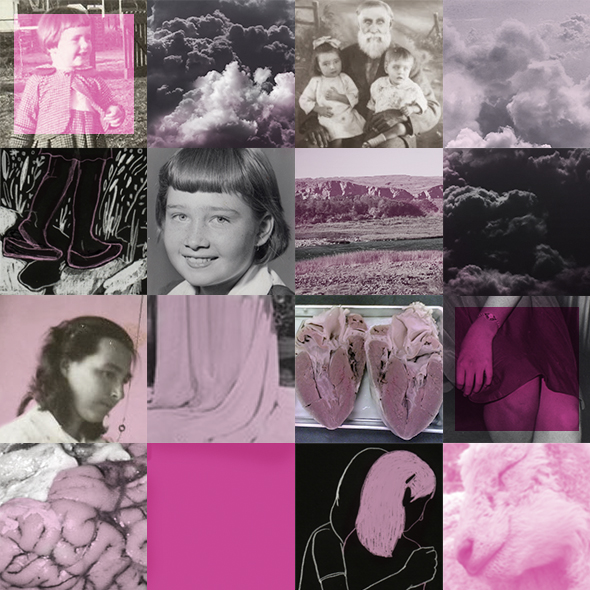

Photo illustration by Lisa Larson-Walker

Susanna always knew that her parents had a special regard for her—not only because she was their firstborn and their only girl, but also because she knew that they had considered her to be ouderwets, or precocious, since her baby days. In a meditation called “The Most Beautiful Places” that she started writing during a visit to our family in Salt Lake City one and a half years before her mental breakdown, she recalls an imaginary conversation she once had with her father “in the clouds of her dreams.”

This daydream takes place at the Orange River, she writes, whose teeming green bisects the arid wilderness of the southern Kalahari region where she grew up. Six-year-old Susanna is climbing the steep bank with two buckets of water. Despite her careful steps along the rocky footpath, water spills over the edges and splashes cool against her feet with their worn, homemade shoes.

Susanna’s father made their shoes. In her daydream he appears in his role as shoemaker: There he is at his iron last, nailing new soles onto his own worn-out shoes with his small-headed hammer. He always looks worried, but when he sees her the creases around his eyes soften and a smile almost begins around his mouth. He likes her. She will ask him about the pink dress she’s been dreaming about.

She asks, “Pa, when Pa gets money again, will Pa buy me some fabric at old Lenhoff’s for a pink dress?”

Her father looks at her. She can see that he thinks she is ouderwets. She knows what his answer will be: “Of course I’ll buy my big girl a pink dress—when I have money again.”

Her father loves her. She knows this, because when her mother cooks afval, or tripe, her father always gives her the sheep’s brain. “That’s why you’re so clever,” he tells her as he dishes into her plate a scoop of brain marrow in a crisp shell of the belly in which it has been cooked. Her mother, Truia, who always gets the heart, reaches an arm around her shoulder from the seat beside her and says, “Big Sister. You must study hard, my child. Ma se ou skapie. Ma’s little lamb.”

* * *

The tree bark beside Doña Quixote is maimed by a deep fissure. Her cottonwood is old, its skin turned from the silvery white of youth to the dark gray of decrepitude. Its coarsely toothed leaves gnaw at the unfunny matter of her own brain. Their yackety-yak drives her down the trunk.

When Doña Quixote reaches the solid ground in which her tree is rooted, Dr. Pompa is there waiting. She offers a steadying hand while the hidalga finds her land legs, then embarks on an interpretation of Doña Quixote’s low IQ score—an interpretation that, as her career-honed empathetic expression suggests, she intends as mitigating. “Due to the amount of scatter between the index scores,” she murmurs confidentially, “the Full Scale IQ is not an accurate representation of the testee’s intellectual ability. Each index should be interpreted as a measure of a separate cognitive ability.”

Doña Quixote finds none of this comforting. Which index, she wonders, does Dr. P suppose her patient would find uplifting? The working memory section? The math? Doesn’t she remember writing that her patient “did not remember the elements of [arithmetic] problems long enough to solve them”? That “When given the opportunity to do the problems on paper, she had the same difficulty reasoning through and performing the correct operations as before”? She who had mentored her own and her neighbors’ children through their Math Olympiad triumphs in high school. She who has a bachelor’s degree in math like her father and has taught the subject in college. She who, like her mother, was ouderwets once upon a time, and beloved.

Don’t worry about your difficulty in mathematics, Das Brain interjects. Mine are still greater.

Das Brain’s apparently empathetic statement whomps Doña Quixote’s limbic system, zaps up anger. Professor Einstein had used these words to protest his supposedly inadequate mathematical skills to an 8-year-old! When Adelaide Delong showed up at her grandfatherly neighbor’s door with homemade fudge and a request for help with her times tables, the supposedly brilliant man accepted the candy but refused to give her his assistance. It would not be fair to the other girls at school, he said.

Quatsch, Doña Quixote expostulates in German. Rubbish. Hadn’t the world’s purportedly smartest man learned anything from being brilliant Mileva Marić’s lover? How could he not have been indelibly impressed that Marić was only the second woman to finish a full program of study in mathematics and physics at the Zürich Polytechnikum? What would fiery Mileva have said to his lame excuse of It would not be fair to the other girls ... ?

Doña Quixote’s rant falls on deaf ears, since the Buick’s vibrations have lulled Das Brain into slow alpha pulses. Soothed with hypnagogic hallucinations, it hears Liebfrau Elsa call in her lilting Swabian dialect, Albertle, my dear naughty little sweetheart. Or was that Mileva?

Now Doña Quixote strolls past the big-tooth maples the city had planted the year she and her family settled in longicuous Utah. “Longicuous” means “remote,” and I’m not surprised you don’t understand it, Sancho, because you don’t know Latin. In language recaptured from a distant slice of space-time, she notices that those saplings have this day come to the prime of their lives.

Just as well that in its westwardly rocking cradle Das Brain is emitting bursts of rhythmic cosine curves that signal delta sleep. Doña Quixote wants to spare Das Brain this part, for she is about to use the Father of Relativity as an antihero, someone living so much through his intellect that the much more important matter of demonstrating his love for those he undoubtedly did love went by the wayside.

Einstein’s failings in matters of the right brain:

Item: Cowed by his father, who had forbidden marriage, he stood silent while Mileva, out-of-wedlock pregnant, sneaked off to Serbia, where, alone and afraid, she gave birth to their daughter, Lieserl, only to have the infant kidnapped by her grandparents, who would not clarify whether Lieserl had died or been adopted.

Item: Bored with their marriage and reluctantly conceding to Mileva’s desire to give it another try, he wrote: You will expect no affection from me. … You must leave my bedroom or study at once without protesting when I ask you to.

Item: Though “known for his interest in children,” he had only the most perfunctory contact with his granddaughter. Poor Evelyn—after learning five languages and earning a master’s degree in medieval literature, she worked as a dogcatcher, cult deprogrammer, and police officer before becoming homeless, sleeping in cars, and diving dumpsters. Poor Evelyn, who sued the Hebrew University of Jerusalem—which earns tens of thousands of dollars per year from her grandfather’s intellectual legacy—for money to move into an assisted living facility. She lost.

As Doña Quixote approaches her house, she wonders whether it was merciful that Einstein had died before seeing Evelyn’s fate proclaimed in headlines such as “Evelyn Einstein Died in Squalor Despite Grandfather’s Riches.” No, she decides, the term mercy applies only if our consciousness somehow survives our death. But what counts as mercy for someone whose brain is destined to be worn out long before her body? This place has only three exits, madam.

Photo illustration by Lisa Larson-Walker

* * *

At her red front door, Doña Quixote stops. She is not yet allowed to enter. I alone cross the threshold, look for my dear, naughty little sweetheart. I find him in the boy half of our his-and-her chair. His computer lies closed on the coffee table. He has turned on his side, his head drooping toward the armrest. His snore is rhythmic and loud. Ma’s little lamb. I have known him since I was 17 and he 19; we met in physics class. I know what he will say, voice blurry with tenderness, when I tell him about the statistically meaningful downward migration of my IQ on the bell curve: “A table, a meat pie, a glass of wine, a hand to hold: What else does a man need to be happy?”

I let myself down gently, lever up the footrest, spoon up beside him. His shoulder pushes up a wave of his mother’s blanket, and that is where I rest my head. He grunts, pets my leg. I think of the belugas’ dissonant chatter as they follow the Moskva home, clots of sound overscored by the strings and winds of the orchestra. I think of the trills of their kin on the Voyager traversing the profound silence beyond the star that gave them life. How strange to the beings of those longicuous worlds the glissandos of the humpback whales.

This essay was originally published in the Georgia Review, and is reprinted here with permission.

---

WORKS CITED

(Return to “This place has only three exits ... ”)

The “Reflection on Dementia Field Notes” sections were initially free-flow rants that incorporated lines I remembered from outside sources. These lines include quotes, either adapted or misremembered, borrowed notions, and received insights that informed my thinking. During my subsequent editing process, I checked the sources in order to acknowledge them, but did not necessarily correct my remembered versions, staying instead with the uses to which I had originally put them. I acknowledge the sources here, in the order they occur:

This place has only three exits, sir: Madness, and Death. René Dumaul. A Night of Serious Drinking. Trans. David Coward and E.A. Lovatt. Boston: Shambhala, 1979.

As for me and my house, [we will serve the Lord]. Joshua 24:15, The Holy Bible. King James Version. Victoria, Australia: The Book Printer, World Bible Publishers, n.d.

... brain dried up from too much reading. Miguel Cervantes. Chapter XXIX, “About the famous adventure of the Enchanted Boat.” The Ingenious Gentleman Don Quixote of La Mancha. Cervantes Project. Est. 1995. Texas A&M University and Universidad de Castilla–La Mancha. Web. Nov. 6, 2012.

Dear Professor Einstein: I understand the world moves so fast . . . up to Sincerely, Albert Einstein. Banesh Hoffmann and Helen Dukas. Albert Einstein, The Human Side. New Glimpses from His Archives. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1979.

... they were part of the brain too. “The Strange and Tragic Story of Einstein’s Brain.” Depleted Cranium: The Bad Science Blog. Jan. 6, 2013. Web. Aug. 13, 2013.

The soup is too hot anecdote. Alex Santoso, citing Einstein historian Otto Neugebauer. “Ten Strange Facts about Einstein.” Neatorama. March 26, 2007. Web. Aug. 1, 2013.

... too stupid to learn. Geetha Bhatt. “Tune in for Intelligence.” Deccan Herald. July 19, 2012. Web. Aug. 12, 2013.

Let us reconcile ourselves to the mysterious rhythm of our destinies ... Winston Churchill, 1931. National Churchill Museum. n.d. Web. Aug. 1, 2013.

Don’t worry about your difficulty in mathematics ... Albert Einstein. Mathematical Quotations Server. Furman University. 1995. Web. Aug. 1, 2013.

It would not be fair to the other girls at school. As above.

Albertle, my dear naughty little sweetheart ... Mileva Marić in a letter to Albert Einstein. Nova Transcripts. PBS. Sept. 9, 1997. Web. Aug. 1, 2013.

Longicuous means remote ... Cervantes, as above.

... those saplings have this day come to the prime of their lives. Grace Paley. “Wants.” Enormous Changes at the Last Minute. New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1985.

How strange to the beings of those longicuous worlds ... This is a reworking of a citation I made in my previously published short story “We’ll Get to Now Later,” from Blessings on the Sheep Dog, Dallas: Southern Methodist University Press, 2002. The original idea about whale sounds in space is from Carl Sagan’s Cosmos, London: Macdonald, 1981.