Robert Frank's The Americans

-

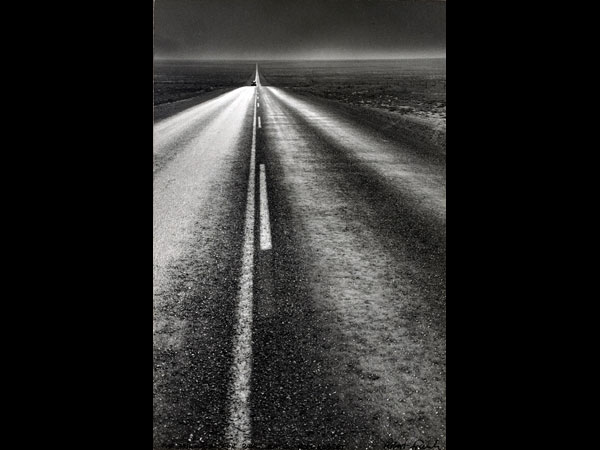

Robert Frank, CREDIT: U.S. 285, New Mexico, 1955. Photograph © Robert Frank, from The Americans.

Robert Frank, CREDIT: U.S. 285, New Mexico, 1955. Photograph © Robert Frank, from The Americans.In the summer of 1955, Robert Frank, a 30-year-old Jewish Swiss émigré, set out on a nearly yearlong car trip across America with his handheld Leica camera and a Guggenheim Fellowship "to see," as he put it, "what is invisible to others." In 1959, Grove Press published The Americans, his book of 83 carefully chosen snapshots from that journey. Initially a flop, it is now regarded as a landmark of modern photography. To celebrate the book's 50th anniversary, the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., is exhibiting vintage prints of the entire series. (The book was recently republished in a gorgeous edition by Steidl.) Frank took pictures of diners, drive-ins, jukeboxes, gas stations, and factory lines, shooting along the peripheries, on the go, capturing a vibrant tempo and aching loneliness that only an outsider could detect. Jack Kerouac, who shared his feel for the restlessness of the road, wrote in the book's introduction: "Robert Frank, Swiss, unobtrusive, nice, with that little camera that he raises and snaps with one hand, has sucked a sad poem right out of America onto film."

-

Frank came to the United Sates in 1947, settled in Greenwich Village, and found work as a fashion photographer at Harper's Bazaar but quit to go his own way. Three friends influenced him enormously. Walker Evans, the great Depression-era photographer, taught him that mundane objects and rundown lives could be the objects of art if treated unsentimentally—while Abstract Expressionist painter Willem de Kooning and Beat poet Allen Ginsberg inspired him to value the improvisational gesture. So, where Evans would spend hours framing his shot and waiting for the right light, Frank placed a premium on immediacy over beauty. Evans described his protégé's technique as "fast bold sure eminently unfussy" and found it "a joy to watch," writing, "If that were a hammer in his hand he would drive the nail in one or two hard fast perfect strokes. … But not usually careful. There wd be a hammer mark in the wood and the boards wd be joined forever."

-

Robert Frank, CREDIT: Charleston, South Carolina, 1955. Photograph © Robert Frank, from The Americans.

Robert Frank, CREDIT: Charleston, South Carolina, 1955. Photograph © Robert Frank, from The Americans.Frank had traveled throughout Europe and South America but hardly at all in his adopted country before taking the '55 road trip. He was struck and puzzled most of all by the blithe segregation in the Deep South, and he devoted much of The Americans to documenting its sorrows and absurdities—well before the civil rights movement gained traction. Most poignant is this shot of a black nanny, or perhaps a nurse, cradling an ivory-white baby—being entrusted with somebody's precious child but (the implied back story tells us) barred from enjoying equal freedoms herself. And how are we to read the baby's expression: as an innocent blank slate, on which a different future might be sketched, or as a chilling indifference, passed down through the genes and doomed to persist?

-

Robert Frank, CREDIT: Trolley—New Orleans, 1955. Photograph © Robert Frank, from The Americans.

Robert Frank, CREDIT: Trolley—New Orleans, 1955. Photograph © Robert Frank, from The Americans.This is the classic Robert Frank photo (he put it on the book's cover), though he snapped it, too, by chance as the subject zipped by. It shows a New Orleans trolley bus, looking like a prison, its passengers separated—segregated—by the bars between each open window. At the front of the bus, a white woman glares with suspicion at Frank's camera—at us. Behind her, two children stare with curiosity. Behind them, a black man looks out with a desperate expression, as if beseeching us—though behind him, a black woman smiles at something off to the side or perhaps at her own thoughts. Beneath this tableau, the trolley's dark, shiny chassis reflects blobs of light and shadow, like a metallic abstract painting. Above it, mirrored panels reflect blurs of people and objects on the sidewalk, like a twisted collage. Frank shot this a few days after cops in Arkansas arrested and detained him for being a "foreigner"—and a few days before Rosa Parks refused to sit at the back of the bus in nearby Montgomery. The image stands as a projection of his outrage—and a harbinger of things to come.

-

Robert Frank, CREDIT: Parade—Hoboken, New Jersey, 1955. Photograph © Robert Frank, from The Americans.

Robert Frank, CREDIT: Parade—Hoboken, New Jersey, 1955. Photograph © Robert Frank, from The Americans.Frank was struck by the hollowness of the country's political ritual, its distance from everyday life. He titled the book's first photo "Parade—Hoboken, New Jersey," but it doesn't show a parade. Instead, it's a close-up of a building that presumably overlooks a parade. We see two windows, flanking a section of brick wall, and above them a flapping American flag, though it's cut off at the top. Two women look out from behind the windows, but we barely see their faces; one is partly covered by a shade, the other by the flag. The photo on the next page (the book is laid out with one photo on the right-hand page and nothing but a caption in small print on the left-hand page) is titled "City Fathers—Hoboken, New Jersey," showing a row of tuxedoed men on a viewing stand, probably looking at the same parade, but this title, too, is comical: a more thuggish, listless, and un-civic-looking bunch would be hard to imagine.

-

Robert Frank, CREDIT: Political rally—Chicago, 1956. Photograph © Robert Frank, from The Americans.

Robert Frank, CREDIT: Political rally—Chicago, 1956. Photograph © Robert Frank, from The Americans.Similarly, Frank called this photo "Political Rally—Chicago," but we see no rally, only a tuba (obliterating the musician's identity), a fragment of two flags, and a stone wall: politics as faceless bellowing. The photo on the book's next page, called "Store Window—Washington, D.C.," shows a brightly lit store window. To the right is a faceless mannequin dressed in a tuxedo, to the left an unevenly hung poster of President Eisenhower: the nation's leader as an empty suit. It was shots like these that roused the editors of Popular Photography to denounce Frank's book as "an attack on the United States," full of "spite, bitterness and narrow prejudices" (as well as "blur, grain … and general sloppiness"). Over the next decade, especially after the book was reprinted in 1968, young artists came to embrace Frank's critical vision and casual aesthetic as (in the words of a critic for the Village Voice) "a quietly ticking time bomb which has yet to be defused."

-

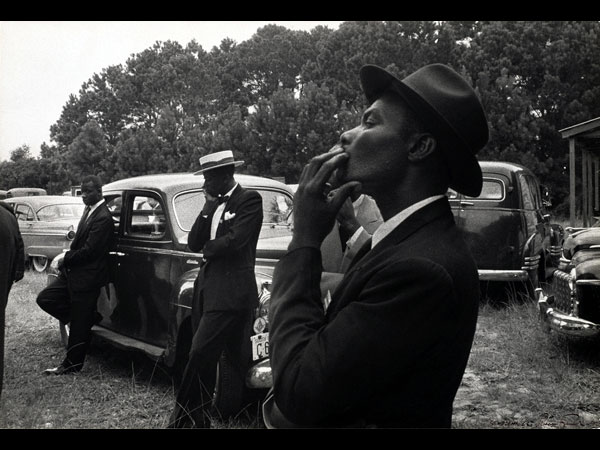

Robert Frank, CREDIT: Funeral—St. Helena, South Carolina, 1955. Photograph © Robert Frank, from The Americans.

Robert Frank, CREDIT: Funeral—St. Helena, South Carolina, 1955. Photograph © Robert Frank, from The Americans.Frank had deep empathy for the downtrodden and for anyone consumed with basic human emotions—love, grief, pleasure, pain. In this photo, called "Funeral—St. Helena, South Carolina," we see nothing of the funeral itself: no graveside coffin, preacher, or flowers; only a few of the mourners, their anguished hands, and cars scattered in every direction, as if abandoned, on the grass, reflecting the disorderliness of death, which Frank saw as a tragic extension of life's natural disorderliness. He once said, "I like a certain disorder; then I can find something in it."

-

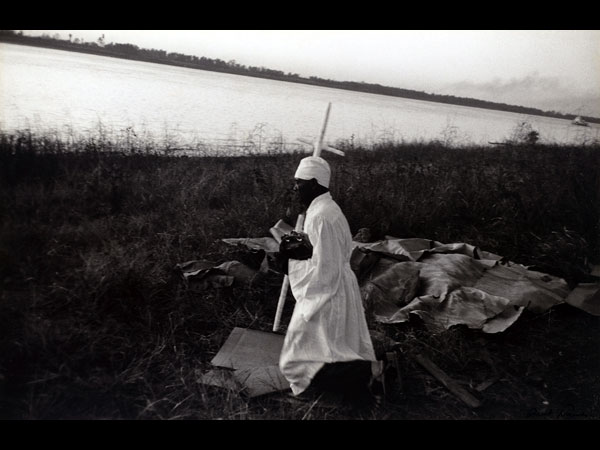

Robert Frank, CREDIT: Mississippi River, Baton Rouge, Louisiana, 1955. Photograph © Robert Frank, from The Americans.

Robert Frank, CREDIT: Mississippi River, Baton Rouge, Louisiana, 1955. Photograph © Robert Frank, from The Americans.As a European accustomed to the casual socializing among strangers at sidewalk cafes, Frank was amazed by how Americans sat side by side at lunch counters without exchanging a word or even a glance. He took a close look at the massive auto factories, where workers were just another set of cogs in the machinery. He grasped the oddity of the drive-in theater, where people watched movies—ordinarily a communal experience—in the isolation of their cars, another aspect of the pervasive obsession with the car and the road, which intensified the nation's appealing speed and vitality but also its appalling loneliness. Yet he also captured tender moments—no less strange to a northern European—of private affection in public parks or, as in this photo, the unembarrassed passion of holy prayer.

-

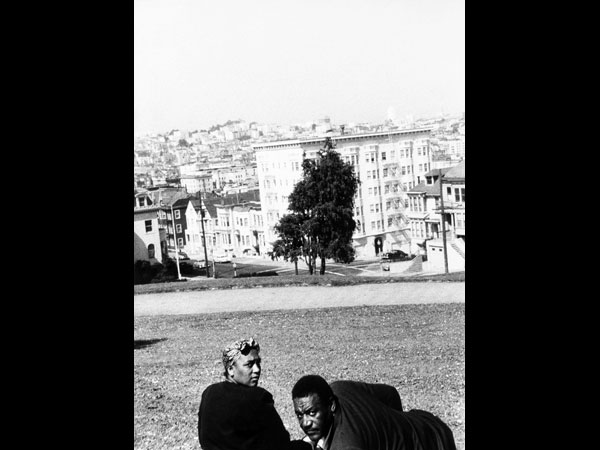

Robert Frank, CREDIT: San Francisco, 1956. Photograph © Robert Frank, from The Americans.

Robert Frank, CREDIT: San Francisco, 1956. Photograph © Robert Frank, from The Americans.Like the Abstract painters and Beat poets of the era, Frank set out to shatter art's illusions. A dominant myth in the '50s was that photography could capture truth—"the decisive moment," in Cartier-Bresson's phrase. To Frank, there was no single truth but rather several truths, and the most compelling might be found in "the in-between moments." He makes no effort to conceal that he is taking—he's making—his pictures. He's an intruder, an outsider looking in. This journey has its risks—not only physical (the man and woman he's sneaking up on here in San Francisco are clearly angry at his voyeurism) but aesthetic. Who are these people? What were they doing before, and just after, Frank locked their images into eternity? The meaning is subject to multiple interpretations, none of which might be right. Frank understood this; he embraced the unavoidable ambiguity as a premise of art and life: the idea, bold in Cold War America, that truth can't be fully known and the only sure thing that artists have is their vision.