Nick Jonas. Paul Simon. Dierks Bentley. Blake Shelton. Beyoncé. What do these music stars, ranging in age from 23 (Jonas) to 74 (Simon), have in common?

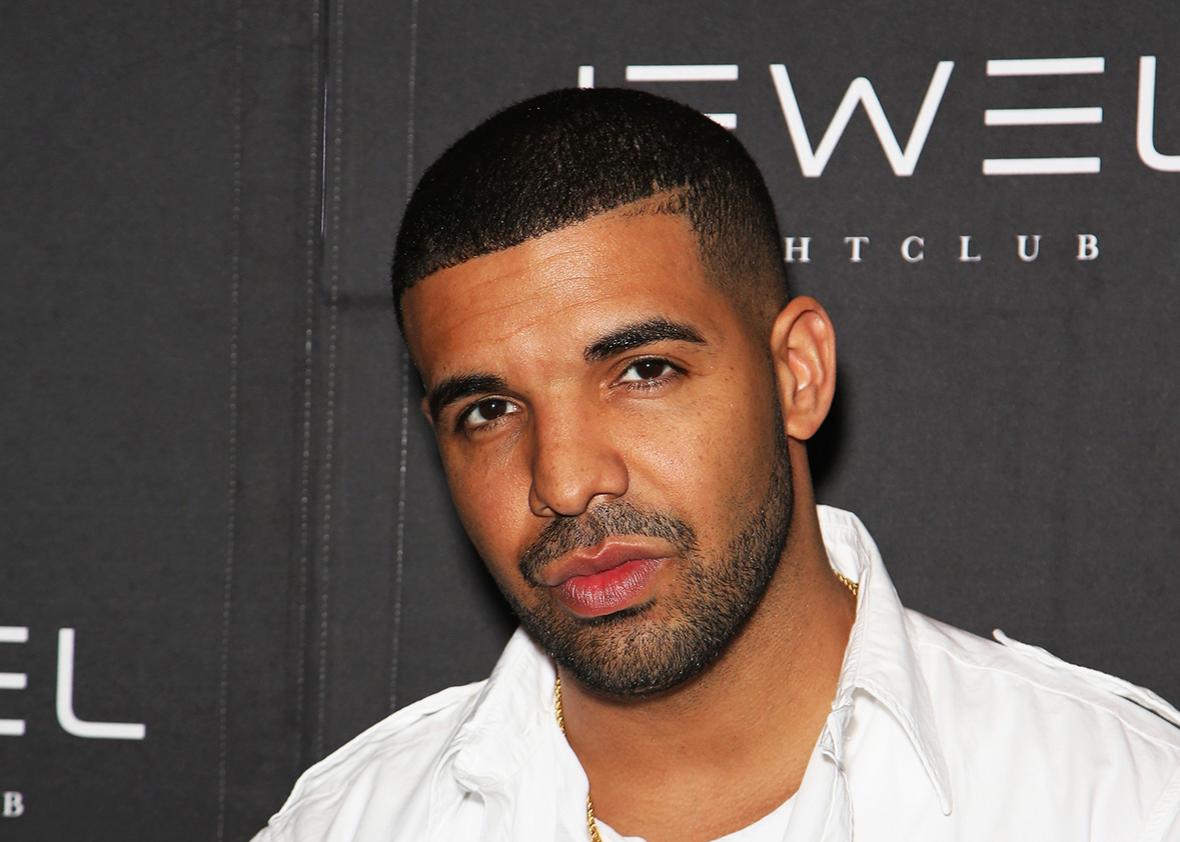

In the last month, Drake has robbed all of them of No. 1 albums in Billboard. Well, “robbed” is a strong word. Drake’s been playing by street-legal mid-’10s chart rules, fair and square. Don’t hate the player, hate the game.

Drake’s current album, Views, is in its seventh week at No. 1 on Billboard’s album chart, the Billboard 200. But Views has only been the best-selling album in America for the first two of those seven weeks. The last five weeks, Drake’s sales have been boosted by Billboard’s new chart math. Since late 2014, Billboard has combined traditional album sales with thousands of single-track sales and millions of streams, to determine the most “consumed” albums in the U.S. The formula is pretty straightforward: 1,500 song streams, or 10 purchased tracks, equal one album sale. Since a pure, traditional full-album sale still counts far more for the chart than does a track sale or a stream, most weeks, the country’s best-selling album is still the No. 1 album. But that hasn’t been the case for five weeks now.

This week, Nick Jonas is Drake’s latest victim, as the former’s pure sales for his new disc, Last Year Was Complicated, were no match for Drake’s “equivalent album units,” in Billboard parlance. During the week, Drake sold about 27,000 copies of Views the old-fashioned way (on CD or as a full-album download), compared with Jonas’ 47,000 in traditional sales. But Drake also racked up about 210,000 sales of tracks from Views, which translates into 21,000 “track-equivalent albums”; and a whopping 110 million streams, which becomes 74,000 “stream-equivalent albums.” That grand total of 121,000 units handily trounced Jonas. Young Nick also racked up thousands of tracks and millions of streams, but these only added up to another 19,000 equivalent albums, giving him 66,000 units total—not nearly enough to overcome Drake’s advantage in tracks, especially streams.

Indeed, over the last month and a half, Drake has set multiple records on the streaming side. According to Billboard, the top six weeks for any album in streaming history were all for Drake’s Views; during those weeks, the album’s tracks were streamed anywhere from 122 million to a staggering 245 million times per seven-day period. This is how Drake keeps stealing the No. 1 spot and spoiling the summer for competing artists. Maybe not Beyoncé or Blake Shelton—they didn’t need more weeks at No. 1. Shelton has scored two prior No. 1 albums. And Bey’s Lemonade was already her sixth consecutive No. 1 album, spending one week on top in early May the week before Drake’s album dropped. (Jonas, too, scored two prior No. 1 albums with his erstwhile sibling act the Jonas Brothers.)

But Dierks Bentley and Paul Simon would have cause for grumbling. After a dozen-year career studded with smash country singles and No. 1 country albums, Bentley would have landed his first-ever No. 1 album on the all-genre Billboard 200. A few weeks ago, his new album Black outsold Drake’s Views more than 2 to 1, but Drake’s gargantuan streaming numbers put him over the top. As for Simon, he would have scored his first No. 1 album in 41 years; Paul hasn’t had a bell-ringer since 1975’s Still Crazy After All These Years (his smash 1986 album Graceland peaked at No. 3). When his new Stranger to Stranger debuted it, too, outsold Views, again by roughly a 2:1 margin, but weak streaming numbers for Simon meant Drake easily held onto the chart penthouse.

This new hierarchy of hits has not gone unnoticed by chart watchers. Read the comments on any Billboard story about the album chart lately and you’ll find choice expletives describing the streaming-driven formula. While Billboard’s approach has been in place more than a year and a half and shouldn’t be news anymore, we’ve seen many more albums this year cross the streams to top the charts. Rihanna’s ANTI reached No. 1 in February with strong streaming numbers, and it returned to No. 1 in early April thanks largely to streaming—it only sold 17,000 copies that week, the lowest sales total for a No. 1 album ever. Later that same month, chart watchers really started grumbling when Kanye West’s The Life of Pablo made a belated debut atop the chart with 70 percent of its chart points from streaming.

Overall, 2016 feels like the moment when streaming really began to dominate the charts. A recent Billboard podcast revealed that streaming is up 62 percent in 2016 over the same period in 2015, and more than 200 percent in just two years. We see the results on Billboard’s Hot 100, where stream-heavy tracks like Desiigner’s “Panda” and Drake’s “One Dance” now routinely command the list. (So much for my recent prediction that Justin Timberlake’s latest hit would be the Song of the Summer—thanks to streaming, Drake’s “One Dance” returned to No. 1 after just one week of Timberlake.) And we see it on the album chart: Last year, the first full year the new Billboard 200 formula was in place, there were five weeks out of 52 where a top-selling album had No. 1 “stolen” by streaming. In 2016, to date, this has already happened eight times in 26 weeks—and again, five of those weeks just happened consecutively thanks to Drake’s Views.

Unlike most chart watchers, I am more bemused than angered by this turn of events. For one thing, a modern-day album chart can’t limit itself to just sales anymore in an age when a top seller like Nick Jonas’ disc shifts less than 50,000 copies in a week. For another thing, Billboard is being admirably transparent about its methodology. The magazine’s weekly online breakdowns of the Billboard 200 reveal all of the numbers behind the top-selling albums for those scoring at home. If that isn’t enough, they give proper credit to albums that would have thrived under the old system. On its website, Billboard publishes a separate chart, Top Album Sales, based entirely upon the old, all-sales methodology. You will find Shelton’s and Bentley’s and Simon’s albums sitting at No. 1 on that chart—a consolation prize, perhaps.

Of course, we longtime chart-followers aren’t just hungry for the data: We want the flagship chart to feel credible. And the new formula isn’t perfect—Billboard does over-weight albums with big hit songs. You could play “One Dance” 1,500 times on Apple Music and that would count as an album sale for Views, even if you never played another track.

But in recent months, I have started to think not only that acts like Drake deserve their extra weeks at No. 1 but that this new approach might, in some ways, be an improvement. In short, I come to praise Billboard’s new formula, not bury it: As albums in the streaming era spend more weeks at No. 1, Billboard’s album chart is re-establishing itself as a credible measure of big-picture cultural influence—something closer to what it was before the SoundScan Era.

Good heavens—am I actually speaking ill of SoundScan? This runs counter to everything chart fans, me included, have believed about the Billboard charts in the last quarter-century.

When it comes to the charts, it is impossible to overstate the importance of SoundScan (later referred to as Nielsen SoundScan after the ratings-measurement company acquired the technology). The barcode-scanning technology, which tallied record sales accurately for the first time, launched in the early ’90s—debuting on Billboard’s album chart in May 1991 and the Hot 100 in November 1991. SoundScan utterly revolutionized how we define a hit. It revealed hip-hop and country music’s massive sales, establishing them as legitimate, pop-promotion–worthy genres; it gave the lie to numerous overhyped classic-rock acts whose sales weren’t as mighty as charts previously showed; and it better reflected the pattern by which artists and songs yo-yo in and out of public consciousness. For example, on the Hot 100, SoundScan clarified that many hit songs open big with an act’s diehard fans, fall off a little for a month or two while radio catches up, then become mass-appeal, chart-topping smashes later. On the album chart, SoundScan revealed that albums open like movies: A title’s biggest week is often its first. Prior to SoundScan, only six albums in chart history debuted at No. 1; after SoundScan, that happened dozens of times per year.

So let me be clear: The invention of SoundScan has been an unadulterated good for the charts and the music industry. Better data is a good thing. But I will confess that, from 1991 to 2014, looking at the SoundScan-fueled, all-sales album chart, I sometimes found myself nostalgic for the corrupt charts of yesteryear. Yes, the fudgable charts from before 1991 when Billboard was phoning and faxing retailers to get their lists of top sellers, and label “persuasion” was rampant. I was nostalgic because albums used to linger at No. 1 longer before SoundScan. It’s difficult to imagine Thriller’s 37 weeks on top, or Purple Rain’s 24 weeks, if better data collection existed in the early ’80s—those long runs on top would have been interrupted by more niche-y albums every couple of weeks.

To understand this, you need only look at the album chart any week after 1991: More often than not, the No. 1 album would be a debut. SoundScan’s better data revealed that most of the time, the best-selling album in America was a new album. The good news was this meant that any album, in any genre, could be No. 1. The bad news was … um, any album could be No. 1. Among the illustrious, culture-conquering albums that have debuted at No. 1 since 1991: collections of standards by Michael Bolton, Rod Stewart, and Barry Manilow; the soundtracks to such cinematic works as Howard Stern’s Private Parts, Gridlock’d, and Hannah Montana: The Movie; crew-rap albums by such adjacent-to-fame acts as Tha Dogg Pound, D12, and G-Unit; long-forgotten follow-ups to better-remembered albums like Live’s Secret Samadhi, Foxy Brown’s Chyna Doll, and Modest Mouse’s We Were Dead Before the Ship Even Sank; three Godsmack albums and five Disturbed albums; a Bon Jovi country album.

Mind you, these albums all topped the chart through legitimate means: selling lots of copies in their first week. What all of the above albums also have in common, however, is they were rapidly in and out of the No. 1 spot. In the SoundScan Era, this became the norm—the top of the Billboard 200 became a revolving door. That door began spinning more furiously in early 1997, when a then-record eight different albums in eight weeks topped the chart. The music industry had adjusted to SoundScan by then, front-loading promotion for new albums and (not unlike a presidential campaign team) driving an artist’s “base” into record stores. And that was when the music industry was healthy. After 2000, when album sales began to erode, the music biz came to over-rely on the devoted fan, and turnover atop the chart only increased. During 2003, 34 different albums topped the chart. In 2006, 40 albums rang the bell. While chart democracy is in theory a good thing, the album chart basically turned into a weekly competition to see which artist’s most indiscriminate, will-buy-anything-with-the-act’s-name-on-it fans would show up in the first seven days.

The number of new chart-topping albums finally peaked in 2013—the last full year before Billboard made the methodology switch to include streaming and tracks. That year saw an insane 44 albums top the Billboard 200 over 52 weeks—an average of a new No. 1 album every eight days. Among that year’s chart-toppers: a compilation of “Spring Break” EPs by Luke Bryan; a collection of Justin Bieber acoustic songs; and nine releases that sold fewer than 100,000 in a week, including new albums from Chris Tomlin, Queens of the Stone Age, and Selena Gomez.

So that’s what SoundScan wrought: greater diversity of high-charting albums but a total lack of consensus. Let’s compare this approach to the corrupt, pre-SoundScan era. I’ll pick every pop critic’s favorite year for hit music, 1984—not only because it was a great year on the charts, but because we can run down every No. 1 album that year easily. Only five albums, total, went to No. 1 that whole year:

- Michael Jackson, Thriller: Jan. 7–April 14, 1984, 15 weeks (plus 22 weeks in 1983)

- Soundtrack, Footloose: April 21–June 23, 1984, 10 weeks

- Huey Lewis and the News, Sports: June 30, 1984, one week

- Bruce Springsteen, Born in the U.S.A.: July 7–28, 1984, four weeks (plus three weeks in 1985)

- Prince and the Revolution/Soundtrack, Purple Rain: Aug. 4–Dec. 29, 1984, 22 weeks (plus two weeks in 1985)

This list is all killer, no filler—even those cheesy Footloose and Huey Lewis albums. And in those pre-computerized times, these albums topped the chart because the retailers Billboard polled (whether they were honest, cajoled, or bribed) all broadly agreed on their pop dominance.

Of course, this list is also a lie: If SoundScan had existed in 1984, at least a dozen more albums would have topped the Billboard album chart that year. The problem wasn’t just record-biz corruption, it was the lack of good data back then. Even superstar albums would typically debut somewhere around the Top 40, then rise to the upper reaches in a week or two, misrepresenting how rapidly those albums likely sold.

For example, in mid–July 1984, the Jacksons’ Victory album debuted on the Top LPs and Tape chart at No. 17—a very high debut for that era. Victory wound up peaking at No. 4 on the chart just a couple of weeks later. But there’s no doubt in my mind that, given the deafening hype surrounding the brothers’ reunion and their high-priced, Don King–produced tour, Victory would have debuted at No. 1 had SoundScan existed then. If we assume this would have happened, you could say the album’s actual No. 4 peak is a miscarriage of data justice. Or you could say it accurately reflects what a stillborn pop-culture event Victory turned out to be. (The album was badly hit-challenged: Only a Mick Jagger duet, likely propped up by heavy radio payola, reached the Top 10. Michael Jackson distanced himself from the project before the tour was even over.)

Of course, a SoundScan-powered 1984 would have had many better albums debut at No. 1. Based on where they debuted and how fast they rose, it’s a safe bet that all of these albums would have started on top: Van Halen’s 1984, the Pretenders’ Learning to Crawl, Rush’s Grace Under Pressure, the Cars’ Heartbeat City, the Ghostbusters soundtrack, Julio Iglesias’ 1100 Bel Air Place, Daryl Hall and John Oates’ Big Bam Boom, Culture Club’s Waking Up with the House on Fire, and Duran Duran’s Arena. Given how underreported country and metal sales were back then, I wouldn’t rule out Alabama’s Roll On, Judas Priest’s Defenders of the Faith, or Iron Maiden’s Powerslave, either. I would have liked to see several of these albums top the charts (especially the Van Halen, Pretenders, Cars, and Hall and Oates albums). But I’m not sure I mind that Purple Rain was No. 1 for 24 weeks instead. Having Prince’s run interrupted by those second-rate Culture Club and Duran Duran albums (each trading on the reputation of prior releases) would have reflected rabid fanbases but not the larger message that 1984 was Prince’s year.

Halfway into 2016, this is clearly shaping up to be the Summer of Drake. And so why shouldn’t Views be this year’s Purple Rain, sitting atop the Billboard chart for months on end? Sure, Views has been overinflated by Drake’s big hit song. Last week alone, “One Dance” racked up 22 million streams, boosting Views’ chart points by nearly 15,000 “streaming-equivalent albums” all by itself. But hit songs have always driven hit albums: In 1984, surely a large chunk of the people who lined up to buy Purple Rain for the five months it was No. 1 were mostly interested in “When Doves Cry” or “Let’s Go Crazy.”

The fact is, no era on Billboard’s album chart has ever been perfect. Before SoundScan, the charts were based on faulty, manipulatable data. The two-decade SoundScan Era was far better, but during this period the chart became a weekly War of the Fanbases. The current album chart is overly skewed toward albums with big hit songs—but it’s based on even more data than we had during the SoundScan era. Now, when an album sits stone at No. 1, you know its tracks are being consumed on every available platform. The truth is the very idea of the album is a construct—it’s a work of art made up of several smaller works—and it has never really been a discrete, indivisible thing. Paul Simon might wish his latest album had been officially declared the No. 1 album in the U.S., but that probably would have required a smash single on Spotify. I’ll bet Paul still remembers what a big, chart-topping, album-inflating hit like that feels like.